Pashupatinath, by far Nepal’s most popular temple, dates back to at least the 1st century ce and has been expanded and rebuilt by various dynasties of kings ever since

A common story about the origins of Pashupatinath is that it was once a forest in which Lord Siva roamed as a deer. Later a Siva Lingam was discovered in the area and eventually a temple was built around it. The name, Pashupatinath, is sometimes translated as “Lord of Beasts.” Dr. S. Sabharatanam of Chennai offers a more precise exegesis: “Pashu does not mean here cattle or beasts, but ‘the one who is fettered,’ ie, all embodied beings. Though the term Pati is generally translated as the Lord, the precise meaning is ‘the One who protects.’ Natha means ‘one who leads,’ and Pashupatinath, therefore, ‘The ultimate Protector and the Leader’ [of those who are fettered].” For our report, we enlisted the skills of reporter Bhadra Sharma and the expertise of Dr. Govinda Tandon to recount the marvelous story of this great temple.

By Bhadra Sharma, Nepal

During the second week of december 2019, while visiting Pashupatinath Temple for this report, I met Bishnu Prasad Koirala, 76. Dressed in the traditional Nepali daura suruwal, he was leading a group of 30 members of a dairy cooperative from his village of Itahari in the Sunsari District of eastern Nepal. A fervent devotee of Lord Siva with three daughters living in Kathmandu, he’s a regular visitor here. “Worshiping Siva, the Supreme God, gives me an inner satisfaction and happiness. A Kathmandu visit remains incomplete without visiting this holy shrine,” said Koirala. It was at his suggestion that his village’s dairy cooperative decided to visit: “When people from across the globe visit Pashupatinath Temple,” he asked them, “why shouldn’t we come here in this holy place and worship God Siva?”

The continuous sonorous tolling of large brass bells, singing of songs praising Lord Siva and chirping of birds makes everyone feel calm. Bands of monkeys pester devotees by snatching food from their hands. Seeing the sadhus living around the temple premises, who have abandoned personal temptations of wealth and luxury—which many others see as essential standards of modern life—one feels the simplicity possible for a human being.

Prachi Karki, just 11, had come from Bhaktapur, just outside Kathmandu, with her family. “Tomorrow is my exam. I’m here to visit my God and pray so that I may perform better,” she said.

The main attractions in addition to the temple itself are Guheshwori, Kirateshwar, 15 Shivalayas, Sati Gate, Kailash, Sleshmantak Forest, and the ashrams of Swami Prapannacharya and Yogi Naraharinath. There are Hindu shrines throughout the area, as well as Jain, Sikh and Buddhist places of worship. It is a huge religious complex with great spiritual, historic and archeological importance. All day, every day, the temple is crowded with worshipers.

“There is no such temple in my country. I found it an amazing place,” Rais Mandan, a youth from Gwalior, India, said while queuing in front of the huge statue of Nandi the bull placed just outside the main temple. For Mandan and his four friends, it took three days to get here from Gwalior. They came by chartered bus with several groups of Indians from Rajasthan, Banaras, Gujarat and Gwalior. “I have found it very peaceful and fantastic,” Rais said, “I prayed with Lord Siva for welfare and happiness in my life and the

HISTORY

The Temple through Time

This great center of Saivism has been revered and supported by Nepal’s kings for 2,000 years

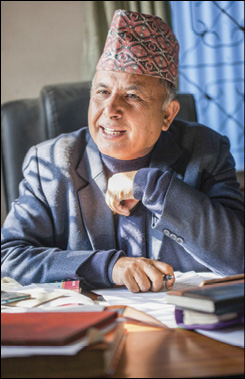

Dr. Govinda Tandon did his PhD at Tribhuvan University, Nepal, on the topic “Cultural Studies of Pashupati Area.” He is a well-known scholar of religion, an animal rights activist, founder of Manav Sewa Ashram to help the needy and former member-secretary of Pashupati Area Development Trust (PADT). He writes here about the religious history of the temple and its Deity.

FROM ANCIENT TIMES, PASHUPATINATH HAS BEEN REVERED as a pious land for self-awareness and liberation and as a place of worship for the devotees to join hands and show respect to the Almighty. Devotees perform sacrificial rites and ecstatic rituals, chant for peace of mind and tranquility and release their hands for service of the poor. Located in the ancient city of Deopatan, three miles northeast of Nepal’s capital, Kathmandu, the temple and immediate area of Pashupati Kshetra is important not only for all Hindus but for all human beings of the world, historically and culturally. In 1979, Pashupati Kshetra was placed on the UNESCO World Heritage List along with six other places in the Kathmandu Valley, shortly after the program was founded. It has enjoyed royal support throughout Nepal’s long history by the ruling dynasties—Gopal, Kirat, Lichhavi, Malla and Shah. The God of all Gods, Mahadev Shri Pashupatinath, and His temple, is a matter of great pride for Nepal and the Nepalese people.

Pashupati as a name of Siva appears in several places in the Vedas, most significantly in the eighth part of the famed Sri Rudram chant of the Shukla Yajur Veda. Historically, the Pashupata sect is one of the earliest known streams of Saivism, arising in the 2nd century bce under Lakulisa and with Somnatha (Gujarat) as one of its principal centers. Its influence remains across India and Nepal, especially in the form of Saiva Siddhanta philosophy.

The beautiful mandap style of Pashupatinath Temple is often referred to by Westerners as pagoda style. The floor area is open on all sides, with a double roof above it. In the adjoining area, known as Pashupati Kshetra, there are charming places of worship and monasteries related to multiple religions: Buddhism has Dandochaitya, Chavihar, Kutuvahal and Maijuvahal; Sikhism has Nanakmath and Nirmala Akhada. There are even old signs of the presence ofj Jainism. More recently, there are the ruins of a 19th-century monastery of the Josamani sect, who were active in social reform. The temple is revered by and open to all who follow the Vedic, Buddhist, Jain or Sikh traditions.

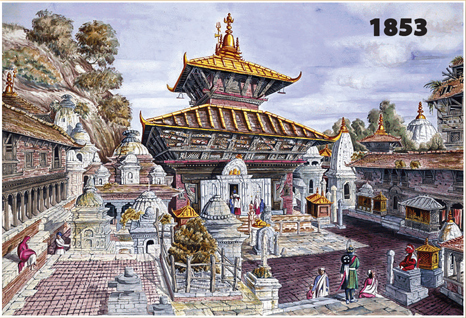

In History

The Gopalaraj Vamsavali, the earliest chronology found in Nepal, mentions that the temple of Pashupatinath was established by a king named Supuspadeva of the first-century-ce Lichhavi dynasty. The temple was looted in 1349 by Sultan Samsuddin of Bengal and the Siva Lingam was broken into pieces. The temple was rebuilt and the Siva Lingam replaced during the reign of Arjun Deva. In 1697, Bhupalendra Malla built a new temple to replace the older one. The temple had five roofs in pagoda style. Eventually this was changed to the present-day two roofs. Both roofs of the temple are gold plated. White granite and silver motifs clad the inside walls. Various carvings throughout the structure depict stories from scripture.

At the beginning of the 19th century, Girvan Yuddha Bikram Shah (1797–1816) dedicated four fortresses near the temple area in the name of Pashupatinath, expanding the temple to a little over one square mile. There are some Buddhist monasteries, Hindu temples, forests, ponds, dharmasalas, etc. Records from the reign of Girvan Yuddha Bikram’s father, King Rana Bahadur Shah (1775-1806), mention the management of various trusts for the worship of Pashupatinath. The Shah dynasty, or Royal House of Gorkha, began in 1559 and only ended when the monarchy was abolished in 2008. Over the centuries, the ruling dynasties regarded Pashupatinath as the royal temple and saw to its maintenance and occasional renovation. In 1986, the Pashupati Area Development Trust was formed with King Birendra Bir Bikram Shah as the first chief patron. It is this trust which now administrates the temple, with the Prime Minister as Chief Patron and the Minister of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation as the Chairman.

Priesthood and Worship

Unlike other Hindu temples, the priesthood of Pashupatinath is not hereditary. The five main priests are Trilinga Bhatt brahmins of the Krishna Yajur Veda tradition from Karnataka, Andhra or Maharashtra in South India. They are followers of Dakshinamnaya Sringeri Sharada Peetham, the first of the monasteries to be founded by Adi Shankara in the 7th century. They must be virtuous, born vegetarians, fully trained in Vedic recitation, initiated in Pashupata Yoga and expert in Saiva Agama. The priestly tradition of Pashupatinath Temple has played a major role in furthering the harmonious relationship between Nepal and India for many centuries.

In addition to these five South Indian brahmins there are Nepalese-born Bhandari helpers within the precincts of Pashupati Kshetra, as well as a large number of other local priests who collectively assist with the temple worship and functioning.

The temple’s main object of worship is a five-faced Siva Lingam. Four face the cardinal directions: Tatpurusha to the east; Aghora to the south, Sadyojata to the west and Vamadeva to the north. Each face has two hands, with a rudraksha mala in the right and a kamandalu water vessel in the left. Ishana, the fifth face, is formless and faces upward. This is the dominant face and the first to be worshiped as the chief part of the Siva Lingam. This formless face is considered the establishment of all forms, the Lord of All Beings, the Divine Master of the Universe, the Supreme Being.

Thousands of pilgrims come to the temple by road from all areas of Nepal—Kakadbhitta, Biratnagar, Birgunj, Bhairahawa, Nepalgunj, etc. Foreign devotees come from India, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, USA, UK, South Africa, Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, France, etc. More than ten thousand are there on any given day.

Entry into Pashupatinath Temple itself is only allowed for followers of Hinduism, defined to include Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism—all of which have places of worship within the precincts. Yagya Raj Ghimire, a brahmin, stated, “Only traditional Hindus are allowed to come inside the main temple premises, not Christians, not Muslims. They can just come and visit outside the temple.” Hindus performing the death rituals are also not to enter the temple.

Trust officials are stationed at the various entry points to the main temple (adjacent areas are open to all for a fee) and can check details such as identity cards, passport, etc., as well as general appearance and dress to make a determination. Only suspicious men are so grilled. “White” people as a category are not allowed, even though some may be in fact be Hindus. With the high volume of Western tourists in Kathmandu, it would be quite a challenge for officials to sort out the few actual Hindus, given that there is no unified system to verify Hindu religious affiliation. Those Hindus so excluded understand the need to control tourists and are content to worship outside the main temple.

For a fee of $8.75, non-Hindus can visit Deer Park, the burning ghats and various monuments constructed around the main temple. The 28 guides of the Pashupati Tour Guide Association brief visitors on the importance of the various places.

Permitted pilgrims enter the main temple area on a stone pathway past the large bronze Nandi and then on to the marble floor surrounding the temple itself. Each of the four sides has a set of double doors clad in silver, with two large brass bells mounted on the floor at each entry. Above each doorway is a toran, a gateway frame with three lintels (crossbeams). Inside each of the four double doors is a second set of double doors which open into the inner sanctum.

The three-foot-high stone Siva Lingam, accessible from all sides, is always covered with a gold and silver kavacham in which are sculpted the faces of Siva. Except for the four Bhatt priests, no one is allowed to touch this Lingam.

As Dr. Tandon explains on page 21, the Bhatt priests are from Trilinga Dravid community of Southern India. The criteria are tough. Candidates must be between age 25 and 40, have completed advance study of Hinduism, be of the Trilinga brahmin heritage, living with their wife (but not having more than one), physically healthy and having no visible scars on their body. The PADT’s priest selection committee makes their recommendations for one main priest and three assistants. Nepal’s prime minister, the trust’s patron, makes the actual appointment—a duty previously carried out by the king.

An attempt was made to end this tradition in 2008 after the country was declared a secular state and the former Maoists rebels came to power. However Nepal’s Supreme Court rejected the government’s move, and strong protests from the Hindu community—including from the Nepalese priests serving at the temple—forced the government to back down.

The priests are extremely well paid: the head priest receives us$70,000 annually and the three assistants get between $35,000 and $43,500 each. To put this in perspective, Nepal’s president, their highest paid government official, receives $15,700 a year. The trust officials justify the handsome salary by pointing out that the priests have to give up their personal life and focus fully on promoting the religious and historical significance of the temple. The head priest is housed inside the main temple premises, while the other priests live in the adjacent area. The present priests—all from Karnataka—are Ganesh Bhatta, the chief priest, from Udupi, with assistant priests Ramkaranta Bhatta from Mangalore, Girish Bhatta from Sirsi and Narayan Bhatta from Bhatkal. Sri Raghavendra Bhatta from Mangalore is priest of the Vasuki Temple. They are required to shave their heads and go about barefoot in the temple.

One devotee, Om Sharan, told HINDUISM TODAY, “We should thank the government of India for sending such devoted Hindu priests. They neither go out of the temple nor eat food given by outsiders.”

In part because of this tradition of Bhatt priests, Pashupatinath is a revered pilgrimage destination for Hindus across India. Whether it be India’s prime minister or president, or Bollywood celebrities, none who come to Nepal return without visiting the temple. The present PM, Narendra Modi, visited in 2014, donating a large amount of sandalwood and announcing a fund to construct a dharmasala to accommodate the increasing number of pilgrims.

The four priests perform the ritual worship every day. The temple doors are opened at 4am; all four appear at the main temple around 8am. The first assistant priest leads the worship of the south face, Aghora; the second the east, Tatpurusha; the third the north, Vamadeva. The chief priest is responsible for the worship of the western face, Sadhyojata, and the upward face, Ishana. Worship ends with gupta puja around 2pm and resumes again at 5pm, with the temple closing after 7:00 pm.

The Great Temple

- Mahasnanaghar: Originally a place for storing puja materials, now being repurposed as the Pashupati Museum.

- Sano Sadavarta Sattal: A former food storage area, now the residence of the priest of Vasuki Temple.

- Rudragareswor Sthana: Temple for the Rudragareswor Shivalinga.

- Badrinarasimha Guthighara: Previously a public rest house built by Badrinarasimha Rana, now an office for the Badrinarasimha Trust.

- Shankaracharya Matha: A monastery built in the name of Adi Shankaracharya.

- Kulananda Jha’s Sattal: A public rest house built by Kulananda Jha, offices of the Pashupati Area Development Trust.

- Gopur: A large gate and building at the western entrance to the main temple.

- Sri Pashupatinath Temple

- Pashupatighata Sewa: A hospice center.

- Pandra Shivalaya: Fifteen small Siva temples along the river’s edge.

- Vajraghar Garden

- Vajraghara Sattal: A former public rest house, presently unused.

- Aryaghata: The traditional sacred crematory.

- Bhandarighara: A facility for Nepal’s Bhandari community.

- Pancha Deval: “Five Temples” to five forms of Siva; the surrounding building is an old-folks’ home. Amarkanteswor/Sureshkanteswor Siva Temple

- Laxminarayan/Ram Temple

- Gaibaccha Sewasthala: Cow shelter.

- Souvenir Shopping Arcade

- Samrajyeswor/Samrajyeswari Temple: Temple built by Samrajyeswari Shah.

- Ved Vidyashram’s Hostel

- Vedvidyashram

- Bankali Dev Uddhyan: Garden named after the Bankali forest.

- New Souvenir Shopping Arcade

- Hamsamandap: A platform named for Hamsa.

- Laliteswor/Kriyaputrighar: Place of mourning.

- Madhavraj Sumargi Bhawan: Event place.

- Electric Crematorium

- Bankali/Kripalu Garden

- Kailash Hill

Native Nepalese priests, called Bhandaris assist the four Bhatt priests, especially in dealing with devotees. These days there are 88 Bhandaris assigned to assist. Three of these, on a rotational basis, are allowed to go to the western face of the temple to directly assist the Bhatt priests. In addition to the Bhandaris, another 1,000 Nepalese priests are employed by the temple for the many shrines and activities of the huge area.

Apart from daily rituals, devotees can offer special worship between 9:30 and 11:15 am on most days by donating money ranging from $10 to much more, as per their financial means. According to Prem Hari Dhugana, chief of the PADT’s cultural division: “Special worship for pilgrims as per their wishes is one source of income to run the temple administration. The only difference between ritual and special worship is that the special worshiper gets easy access to the temple, milk is offered to the Sivalinga and the worship is conducted by the main priest.”

The Burning Ghats

Walking by the Bhashmeshwor Ghats along the Bhagmati River, immediately adjacent to the temple entryway, is a striking part of the experience of Pashupatinath Temple. On any given day there may be a half-dozen flaming cremation pyres, each attended by wailing relatives. For the temple devotees, this can be a stark reminder of the ephemeral nature of our physical existence and a motivation for more intense worship and communion with the enshrined God Siva. It is the common belief here that departed souls find peace upon being cremated here. The fires burn day and night—an average of 18 in a 24-hour period.

There are hospices adjacent to the temple—one just to the right of the entry stairs—where the dying are brought by relatives for their last rites. A traditional physician known as Ghatevaidya attends to and comforts the dying. He or the relatives will constantly recite the name of God in the dying person’s ear to ease their transition from this world to the next.

The PADT trust manages the funeral rituals within the temple precincts. A few years ago they built an electric crematorium a short distance downstream from the temple entrance and Bhashmeshwor ghats. But many still want to cremate their dead in the traditional manner, with firewood at the riverside ghats.

Of the total of twelve ghats, the two at Aryaghat are the crematoria for VIPs. “In the past, only members of the royal family and the head of the government or ministers used to get cremated with state honors at the Aryaghat,” stated Saroj Ghimire, an official of the ghat Service Center. “The rest of the people cremate at Bhashmeshwor ghats.” Today one of the two ghats at Aryaghat is open for the use of the general public, with the other still reserved for VIPs. On most days, both are unused.

To cremate at Bhashmeshwor ghats, one pays a fee of $10.55; for Aryaghat, the fee is $44. In addition, there is a $1.76 registration charge. After getting their registration receipt, the family can obtain the required timber from the temple for free. There are 30 workers who handle the cremations. They are paid between five and ten dollars, or more by wealthy families. Villagers and some poor people will perform the cremation work entirely by themselves.

Bodies are first brought to Brahmnal, a stone bed on the river just below the temple entrance, where the huge quantity of milk offered at the temple’s main Siva Lingam shrine flows into the Bagmati River. They are then carried to a platform for the cremation, which will take several hours. Once the body is consumed, the pyre is pushed into the river and washed away.

The Teej Festival

The Bagmati, unfortunately, is getting polluted, despite several measures implemented to keep it clean. This is especially a problem at low flow, in the two months prior to monsoon season. The ever-increasing number of pilgrims and generally unmanaged development of Kathmandu are blamed.

To revive the lost glory of the Bagmati River, the PADT is working on two projects in collaboration with Asian Development Bank. One would implement rainwater harvesting to augment the temple’s internal water supply. Another is a pipeline to divert water from the river upstream at Sundarijal, a forested area nine miles north of Kathmandu, and reintroduce it just above the temple—bypassing all the in-between users.

Efforts to purify the river by regulating pollutants are also underway. A major government project is the Guheshwori Wastewater Treatment Plant not far upstream from the temple, which can treat eight million gallons of water a day and substantially improve the river’s water quality. It is expected to come fully online this year.

Sadhus

Nine categories of sadhus are said to frequent Pashupatinath: Natha, Udasi, Bairagi, Birmal, Aghori, Vaishnava, Kapalik, Josmani and Brahmachari. All perform their spiritual practices, sadhanas, within their respective places, popularly known as akharas, within the complex. Lifestyle and sadhanas of sadhus differ from one group to the next, although the ultimate goal of all is God Realization.

Our reporter met a few of these sadhus, starting with the Nathas, who are identifiable by their pierced ears with very large earrings. Here they number just ten and live up on a nearby hill, stay clean and neat and don’t eat meat. “Our day starts with two assigned people playing the nagara flat drum to mark the official beginning of our sadhana and ends with the arati to Gorakhnath [their founding guru] at 5pm,” explained Yogi Omnath. “Burning the dhuni fire, teaching people and worship are our main sadhanas.”

There are three Aghori sadhus. Unlike the Nathas, they prefer to live close to the burning ghats, don’t care if the place is dirty and eat whatever they get—usually from a bowl made of a human skull. They cover their bodies with ash from the burning ghats, wear black clothes, often keep a dog with them and partake of marijuana and alcohol. They live a different kind of life, one which seems strange to others.

Vaishnava sadhus wake at an early hour, kindle a fire, bathe and smear ashes on their bodies, then chant Siva mantras. “We Vaishnavas just eat plain rice and lentils and take no alcohol and no meat,” said Radha Baba, who was sitting cross-legged and holding a rope-made snake in his hand beside the Ram Temple. This temple is very popular with Vaishnava sadhus; in fact, they are a majority of sadhus here.

Maha Shivaratri

Many of Nepal’s 50 official festivals are observed at Pashupatinath Temple or the nearby area, but Maha Shivaratri, the 13th night/14th day of Phalgun (February/March), is the most famous by far, with a reported million-plus devotees in attendance each year. Most are from Nepal, with large numbers from India and some from Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, and other parts of Asia, as well as Europe and America.

Hundreds of sadhus from India and elsewhere arrive at the temple three days in advance to join the many Nepali sadhus for celebrating the festival. Their presence enhances the festival for all the devotees, as they sit around their dhuni fires, sing Siva bhajan, dance throughout the night and offer blessings to all who approach them.

Wealthy devotees of Lord Shiva arrange for free food, fruits and water. The temple provides firewood to keep devotees and sadhus warm. There are emergency medical facilities and a strong security presence by the Nepalese army and police forces.

“If you visit the temple premises on that special day, you feel as if you are in heaven fully relaxed. Unlike wrangling seen over minor issues for petty personal interests, this temple gives you a religious vibe all the time—be it on a quiet normal day or at a festival,” says Om Sharan Aghori, one of the bhandaris assisting the head priests.

Om feels no one is as lucky as the bhandaris, priests and brahmins of Pashupatinath. “We are disciples of Lord Siva. We don’t feel uncomfortable in Pashupati temple even in extreme cold or heat. It’s because of Lord Siva’s power,” he said.

As there is no large gathering area inside the temple, the hundreds of thousands of devotees circulate quickly through the temple, whose four main doors are kept open all day and all night. It is so rushed on Maha Shivaratri that the main priests do not perform any extra ceremonies for individual devotees but only do the main worship.

Under the monarchy, the royal family never missed attending special functions at the temple on Maha Shivaratri. Today the head of state, other high-level dignitaries as well as the former royal family themselves carry on the tradition.

Many other festivals are also observed at Pashupatinath, with the most colorful being Teej, the annual festival of Hindu married women in Nepal, during which they fast and pray for the well-being of their husband and family. On this day the temple is only open to women, who come in large numbers all dressed in red (sometimes blue) wedding saris. The three-day festival includes dancing, singing and on the last day a feast prepared by the men. It is considered the Hindu festival of womanhood.

The Sadhus of Pashupatinath

How to Visit the Temple

Pashupatinath temple is easy of access, being virtually adjacent to Tribhuvan International Airport, and just a short distance off the eight-lane Ring Road that encircles Kathmandu. There are several four to five-star hotels within four miles. Near the temple are a few three-star hotels. as well as other less expensive accommodations. There are many places to eat.

The north-facing view of the Himalayas from Pashupatinath Temple is always fascinating. With regard to weather, even in the hot summer the atmosphere in Kathmandu seems to be cooled by natural air conditioning. Likewise, the winter does not seem so cold in Kathmandu. Normal sweaters and jackets are the common attire.

Upon entering the large park-like area adjacent to the temple, one first encounters the numerous street vendors lining both sides of the road selling a leaf plate—belpatra—for worship. It has marigold flowers, beads, a lamp, incense sticks and more. Open from early morning to 8pm, these stalls also sell rudraksha beads, shaligram and other religious items. Elsewhere on the temple grounds is a large bazaar with much more for sale.

As pilgrims enter the second entrance gate to the main temple, they are directed to the highly organized footwear lockers where they may check their shoes, a facility established a few years ago by the PADT to ensure pilgrims could get their shoes back safely. It’s open from 4am to 8pm. From there one can enter the temple, attend worship and visit nearby shrines.

Future Plans

In 2017, the PADT announced progress on a plan for the future development of the temple. The chairman, Jeevan Bahadur Shahi, explained, “It will be a significant contribution to the tourism of Nepal if the Pashupati area can be made a center of attraction for foreigners by developing it as a study and religious site.” He added that it would be a contribution to national economy if Pashupati area is developed as an open museum.

Pradeep Dhakal, member secretary of the Trust, told HINDUISM TODAY in December 2019 that it would take another year and a half to finalize the plans. They include upgrading the existing Nepal Veda Vidhyashram, presently teaching only Sanskrit, to a more comprehensive Hindu Research Institute; establishing a Sanskar Mandal to teach about Hindu rituals from birth to death; promoting Siva bhajan and dance; and developing the area as a tourist destination for non-Hindus.

A summary of the master plan, intended to cover the next hundred years, is available on the temple’s website: pashupatinathtempletrust.com/master-plan-padt/. It addresses the needs of three component areas: the Core Area, which is mainly the Pashupati and Guheswori Temple precincts; the Consonant Area, which encircles the preceding; and the Continuum Area, which is everything else within Pashupati Kshetra. There is particular concern to deal effectively with urbanization and encroachment upon the Continuum Area. At this point the master plan is still in its first phase, gaining consensus on the overview of what to do. The second phase will be the detailed plans. Phase three is actual construction.

Life’s End: the Cremation Ghats