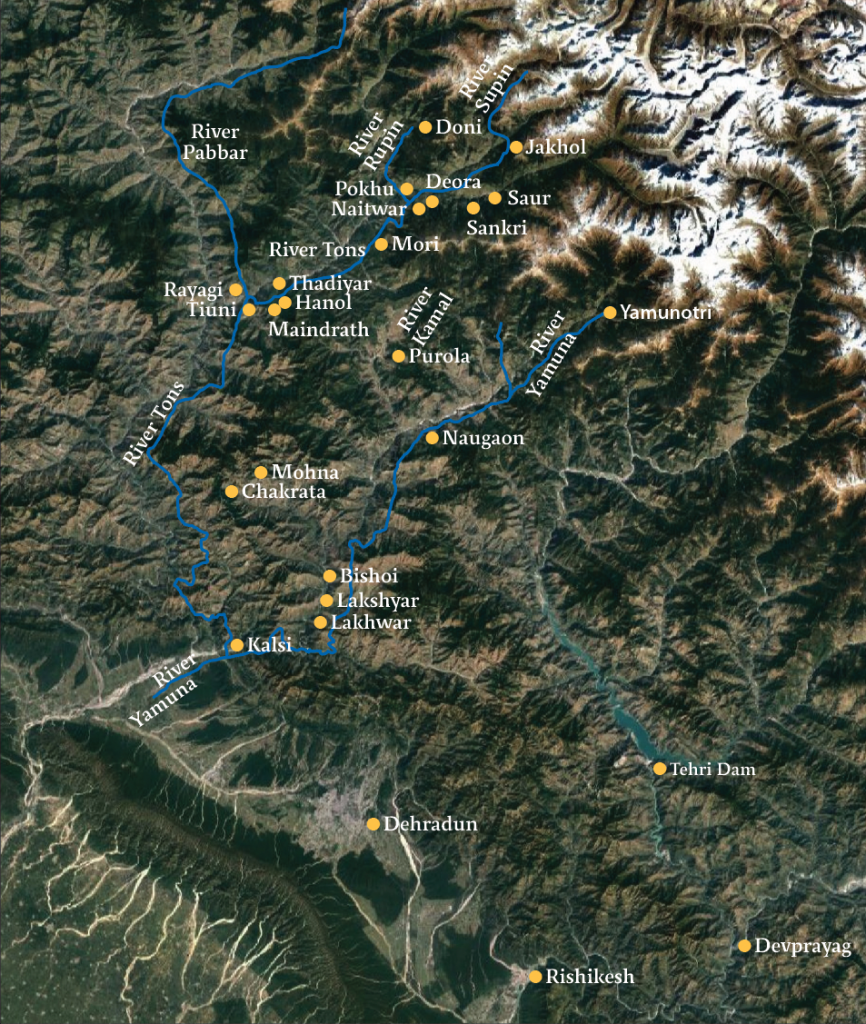

Trek the highlands to the sacred masterpieces along the Tons River as it flows down from the Himalayas to join the Yamuna River

By Dev Raj Agarwal, Dehra Dun

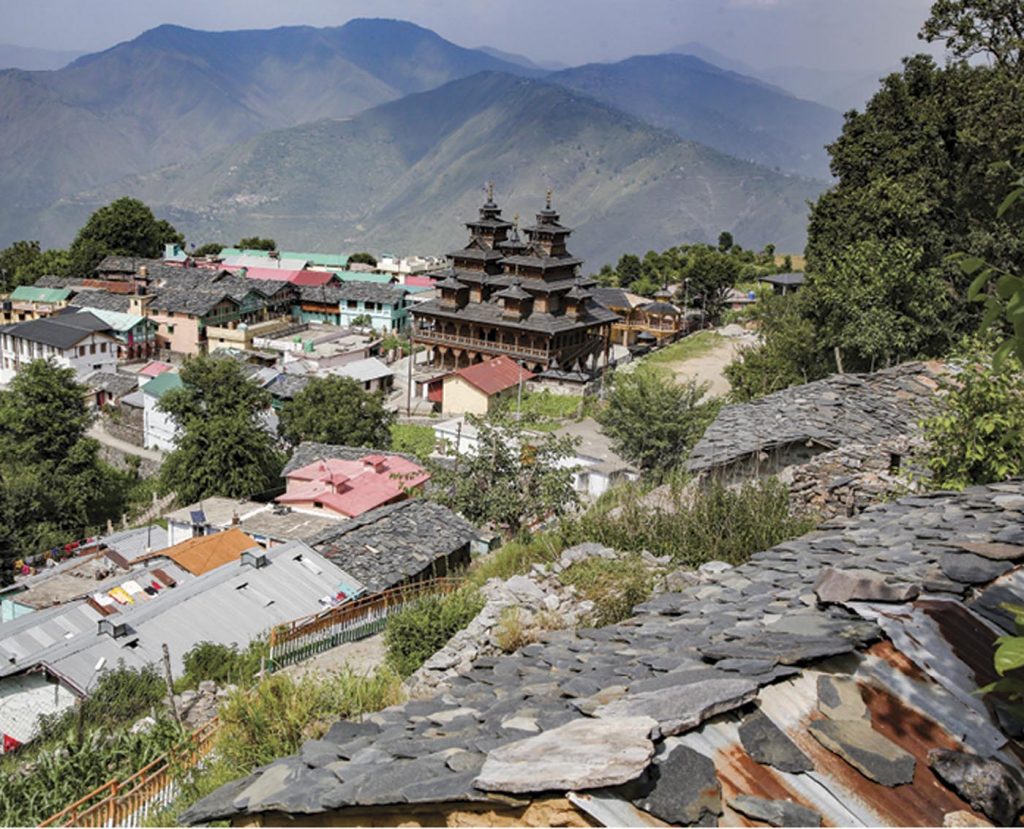

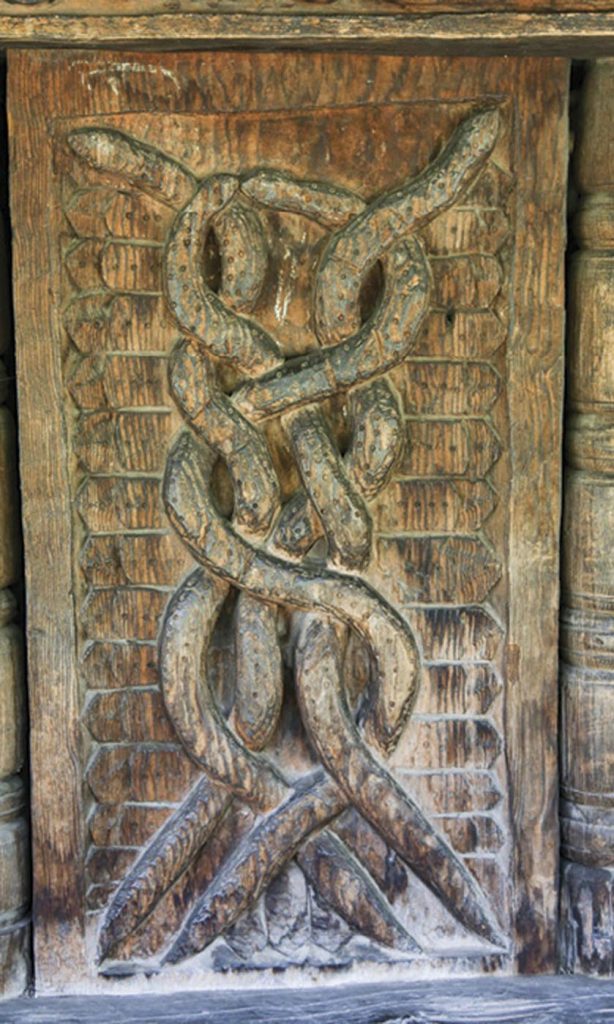

The tons river in the westernmost part of uttarakhand is the largest Himalayan tributary of the Yamuna. From its highest villages down to its confluence with Yamuna near Dehra Dun, the valley is known for some of the most beautiful carved wood temples of the Himalayan region. Following a strong local tradition, these sacred edifices are decorated with intricately carved motifs depicting scenes from the Mahabharata and Ramayana, and their gable roofs are beautifully covered with stone slates.

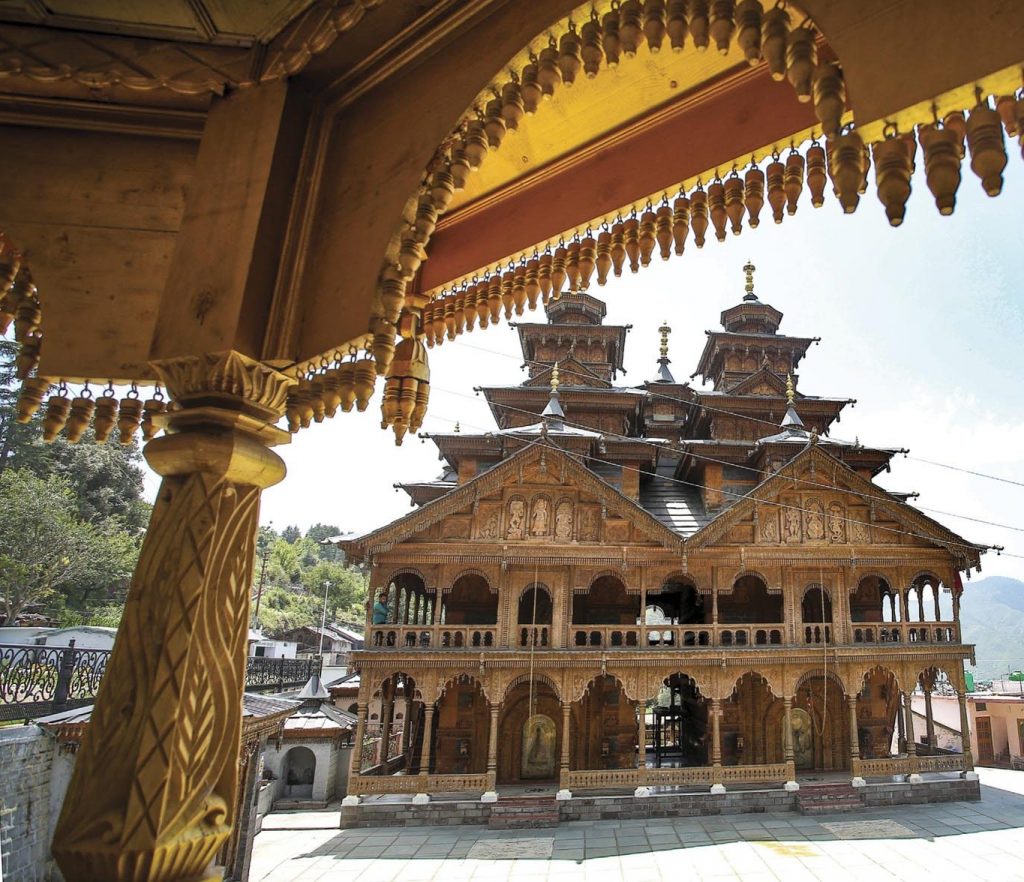

New temples continue to advance the tradition, including Bishoi (at top) which is on the site of an old temple. The temperate to subtropical climate of the Tons Valley lends itself to life in village-level communities. Perhaps due to natural hazards—such as earthquakes of 8.0 and higher that occur every century—the Gods, Goddesses and devas revered here are primarily of a fierce nature. I saw some of these temples for the first time forty years ago. Frequent trekking trips to Har ki Dun brought me back many times.

During monsoons this year, I proposed to Hinduism Today that I take time to cover these temples for the magazine. Accompanied by my son, Arnav, I was able to do so in December 2021, after the monsoons and during a low point in the pandemic.

The evolution of these temples can be traced by starting at the top of the valley. The village of Jakhol, 130 miles from Dehra Dun, is located on the Supin River, which 14 miles downstream joins the Rupin to form the Tons. Nearby is the high-altitude Govind Pashu Vihar National Park, home to a variety of exquisite Himalayan flora and fauna, including the endangered snow leopard. Most of the temples in this part of the valley are dedicated to Someshwar, a form of Siva, and follow the oldest traditions of architecture.

Someshwar Temple

Jakhol is an old, fairly large hill village at an elevation of 7,200 feet. About 300 wooden houses shelter a population of 1,600, including at least 20 families of carpenters who are engaged in building homes and temples here and in surrounding villages. Jakhol’s centrally placed temple to Lord Siva, the largest in this area, is a magnificent example of the Nagar style of architecture followed by most of Someshwar temples (photo next page).

Based on a rectangular platform of wooden beams and stones, the temple walls are raised with alternate rows of stone and wood. The beams and columns are securely interlocked. Beautifully carved wooden slabs depict figures and tales from the pantheon of Hindu Gods. Heads of elephants adorn the sides of thick, strong vertical wooden columns. The facade is decorated with figures of elephants and birds. The heads of two goats, symbols of fertility, are artfully carved above the main door.

Inside the Temple

The Someshwar temples are as simple on the inside as they are ornate on the outside. The murtis are kept on a low pedestal. The doors to the chambers are very low. This is a common feature, but I could not find out the reason.

Decorating the central ridge pole are wooden peacocks, mountain pheasants and goats. Wooden bells hang from the corners of the roof. The sanctum sanctorum has a two-story roof covered with a metal canopy. As in all Himalayan temples, hundreds of wooden tassels dangle from the borders, making unique sounds as they swing in the breeze.

On either side of the main door are two high pedestals, where the temple drummers sit. Facing the temple is a huge shelter used by people for meetings. During festivals, all the young boys and girls giggle and dance here, grabbing the opportunity to meet freely. The arrival of a motorable road two decades ago brought changes, including the replacement of the courtyard’s thick slate tiles with modern ceramic tiles.

The courtyard was deserted when we visited, because Samsu, as they lovingly call the Deity, is on the annual tour to 22 villages in the area, 18 of which have ornate wooden temples for Him. The Deity is presently in Saur, the next village we will visit. Because the priests travel with the Deity to each village, no temple worship is performed in any of the other villages until His return; so, all temples on this circuit except for Saur are presently closed.

We asked Dr. Sabharathanam of Chennai, a scholar of temple traditions, about this unusual pattern of moving the Deity from village to village. He had not heard of it before, but speculated, “In the Mayamata text of temple construction and village design, it is said that many parts of the Earth are occupied by invisible forces, both benign and harsh. When a village or city or temple is to be formed or constructed, certain activities such as ploughing the land, assembling the cows to stay there, etc., should be undertaken, and the concerned priests or chief should request harsh forces to leave the place in order to be occupied by the people and the chief Deity. If such propitiatory rituals are not performed, such forces would continue to exist there. I think in this case the Deities are moving with the local priests who know the traditional process of ameliorating these harsh forces.” A small temple in each village with a part-time priest would not have the power to accomplish this. People in the area told me that even though the one Deity lives away for long durations, their lives are fulfilled once He visits them.

When I visited this area 30 years ago, villagers told me the temples were dedicated to Duryodhana, the villain (in most interpretations) of the Mahabharata. The name Samsu, which they use for the Deity, originally referred to Duryodhana and honored him as a great king of this area. In recent decades, after being questioned why they worshiped Duryodhana, they began regarding the Deity as Someshwar, a form of Siva, which may have been the case originally

Saur Village Hosts Someshwar

Auspiciously, the Someshwar Deity arrived in Saur from Jakhol the day before us. This otherwise-silent village of the upper Himalayas, sitting on a slope below a thick forest of cedar trees, is bustling with activity. This is the one time of year to receive the blessings of the Deity here. It is a time to thank Someshwar for their good health, fruitful crops and prosperity—and to pray for continued blessing. The villagers sing and dance in thanksgiving and invite relatives and friends to feasts in their homes.

We are told the Deity arrived on a silver palanquin carried by two young men followed by His six priests and a long procession of people dancing to the tune of hill songs played by a band of trumpets and drums. It is monsoon season and agricultural activities are at a minimum, so the entire village has turned out for the event. They sing praises of the Deity in the local language, a dialect of Garhwali I do not understand.

Upon arrival, the Deity is placed inside the temple, which sits on a plateau with a stunning view of the valley. In the tradition of Someshwar temples, this one faces west. Not an inch of the structure is bereft of intricate designs carved in the wood by local artisans. Beautiful lacework, floral patterns, animals, birds and characters from Ramayana and Mahabharata—all stand out prominently on the rough surface of the wood slabs, posts, beams and panels.

According to Kirpal Singh, the chief priest, “Someshwar and other Deities of Tons valley came here from Kashmir during the time of the Mahabharata. They were established here after killing many demons, including Kirmir Danav, who had terrified the entire Tons valley. Someshwar not only brings peace and prosperity to His adherents, but brings rains and good crops, saves us from ailments and sufferings. No food grain is used inside the temple for prayers. We light pure ghee lamps, incense and offer many kinds of sacred leaves in prayers. We have secret mantras in our language which the priests learn from elder priests. No Vedic rituals are performed by us—we have separate family priests for those—nor do we accept any offerings for any rituals. Being the family Deity of all living here, Someshwar is remembered with Lord Ganesha in all rituals at home.”

The mali, a priest temporarily possessed by the Deity, is the bridge between the Deity and devotees. When the Deity is invoked to enter the mali, the priest goes into a trance, shivers, cries and then begins answering questions by any person who comes to him for the solution to a problem. The services of the mali are very important for the people, for he is the God personified. His verdict is almost invariably accepted by everyone, for it is believed that whatever the mali says is the Deity’s command. One person tells me of a complex land dispute between two villages that was ultimately taken to the mali and his resolution accepted by all. Another tells me consultation with the mali is so successful that only a handful of cases end up in local courts.

While we are doing interviews one early afternoon, villagers start gathering in the temple courtyard. Soon the outer chamber of the temple is packed to capacity with devotees and a priest. The drummers, settled on either side of the facade, accompany an hour-long ceremony inside the temple. After the rituals, a beautiful silver bust of the Deity is brought outside and displayed for darshan in a small tent. In addition to the silver face mask of Someshwar, we see murtis of Buddha and Parvati. A huge crowd has gathered. Important villagers sit in front of the Deity with the headmen of adjoining villages. Someshwar’s six priests sing and dance to the beat of drums for thirty minutes. Soon the Deity possesses one of them. As the mali, he dances with slow, delicate steps and meaningful gestures. It is a serious moment. Guests from surrounding villages question him about the weather, crops and the pandemic. In the past, serious fires gutted a number of houses, so many questions address this threat. On the pandemic, the mali says they will not be much impacted. After the questions are answered, other priests join the mali and dance for an hour. Later the merry-making men, women and children, wearing their home-woven woolen ceremonial clothing, dance in circles till late evening.

Over the next month and a half, the palanquin of Someshwar will visit all 18 villages in the area, moving every two or three days.

At the Confluence

Ten miles downstream of Saur is Naitwar, where the Tons River is born with the confluence of Supin and Rupin. This area has several temples of note. The one in Kotgaon, near Saur, is just as beautiful as Saur’s and has an equally commanding view of the mountains.

A second important temple is that of Karna in Deora, a few miles downstream. This may be the only Karna temple in Uttarakhand, though there are others in India for this key figure in the Mahabharata. Karna is the son of the Sun God, Surya, and Kunti, mother of the Pandavas. Though a close friend of Duryodhana in the story (eldest son of the Kaurava clan), Karna is regarded as an upright person, so the question of why a mortal person is being worshiped has apparently not arisen here. When Karna died, his followers wept profusely, with the tears becoming the Tamas (“sorrow”) River, now known as the Tons.

The Karna Temple is ornately carved and decorated, though today the wooden panels are coated with paint. Inside the sanctum sanctorum are murtis of Karna, Shalya Maharaj (his charioteer), Renuka (wife of his guru, Parusharama) and a Shivalinga.

A tantrik by the name of Lapavda is believed to have brought the statue of Karna from Champavat in eastern Uttarakhand (360 miles by modern road). Karna is said to have directed the tantrik to establish a temple to him. Karna is the family Deity of the people of many villages around Naitwar. As elsewhere in this region, the priest has a set of secret mantras in the local language which he recites during worship. These are orally passed down to each new generation of priests.

The architecture here is similar to that of Someshwar temples, with open pathways around the temple for circumambulation as a common feature. The temple door has a quadruple frame with a small door, all covered with brass and embossed figures of Gods. Devotees actually nail coins to the wooden doors and frames of temples as a form of offering.

Manoj Prasad Nautiyal, one of the priests from Deora’s 20 families of priests, tells me, “We are simply pujaris. We do not perform any ritualistic duties outside the temple, nor do we accept donations. At home, we call upon brahmin priests to perform the rituals.” Inside the temple, he says, they offer lamps and incense while reciting secret mantras for Lord Siva as Bholenath. The name of Raja Karna is recited along with Lord Ganesh. Newlyweds visit the temple for blessing, while other devotees come to seek favors from the Deity. When the wishes are fulfilled, devotees return to the temple with offerings of halwa sweets in thanks.

A third temple here is to Pokhu, the God of Justice. Located just above the confluence of the Supin and Rupin Rivers, it has been renovated beyond recognition from its original form. This temple is regarded as a court of law. Pokhu is believed to be a supernatural being sent to protect a Goddess from ferocious mountain demons. In accomplishing this, he becomes very proud. Realizing the error of his ways, he sinks himself upside down in the ground as an act of penance. The Goddess forgives him, and he becomes renowned for being so just that he did not even spare himself from punishment.

Pokhu remains, however, a feared being,.His murti in the temple is kept in the dark, and no one dares see it in bright light. The priest, Jai Veer Singh, performs all activities inside the temple with his back towards the altar. Jai Veer is also the mali of the temple, channeling Pokhu’s insights and decisions. He tells me that animal sacrifice is practiced here, saying, “The life has to be taken to save someone’s life.”

Devotees come to Pokhu in the event of land disputes, family problems, fights, thefts, ailments, etc. They have more faith in the decision that comes through the mali than in any court or doctor. In almost all cases, this decision is acceptable to all concerned.

In my presence a young man is brought to the temple, carried by two men. He is unconscious and appears to be dead. He is not responding to anything. Three persons drag him to the facade of the temple, where Jai Veer, as mali, explains that the man is suffering from a spell cast by powerful forces. He tells the story of the recent death of the man’s wife, then throws some rice grains on his body. The man comes to his senses in a fraction of a second. This appears to be a kind of exorcism. The man’s attendants later tell me that everything the priest related was accurate.

The Temples of Doni

Twelve miles northwest of Naitwar, upstream in the valley of the Rupin River, is the village of Doni. Because modern roads reached here only a few years ago, Doni’s temples are still well preserved in the old style. There are three temples of note here, all close in design to the temples of neighboring Himachal Pradesh, whose artisans are often hired to build temples in this area.

The first is Sherkudiya, a tower-shaped shrine standing in the middle of the village. It is a tall, straight structure of stone and wood, with a cantilevered wooden balcony around all sides of the top. Sherkudiya is one of the ministers of Mahasu (see next section of this article). Like Pokhu, Sherkudiya is known as the God of judgment and wise decisions. The temple murti travels among five villages each year; it is presently in the temple at Bhitri.

Twelve nearby villages have joined together to extensively expand this temple. Artisans have been brought from Mandi in Himachal Pradesh for the task. According to Poti Singh, age 84, the original structure will not be affected by the renovation. He opposes the use of colored paints on the temples of their village—something that becomes more and more an issue the further down the Tons Valley one goes.

Two of the finest wood temples we encounter in all the valley are those of the Goddess Vithasin here in Doni. The older of these is closed for all practical purposes, though the open space around it is still used for annual festivals. The newer one is similar in design to the Sherkudiya temple, especially its tower shape, but more ornately carved. The main part sits on a high platform of stone. This floor is shorter in height but with a larger balcony. There is fantastic lacework inside.

According to priest Surajmani Gaur, Vithasin is an incarnation of Parvati. Once in five years She goes to Bharadsar Tal (a high-altitude lake ) for a holy dip. The daily prayer ceremony in these temples is simple, as in other temples. “Till now we were not exposed to the outside world so much, so our temple heritage has been kept protected. The extension of the Sherkudiya Maharaj temple is a big challenge for us.”

The older and essentially abandoned temple is to the north of the village. It is single storied, with beautiful corridors all around. Starting from close to the ground to the ridge, the finely cut shingles of stone slate are placed meticulously on the roof. Figures of Gods and Goddesses and unique geometric patterns embellish the corridors. One villager estimates it to be one hundred years old, but it appears much older to me.

In the Realm of Mahasu

Eleven miles downstream from Naitwar is the junction of two roads at Mori. One goes east to the valley of the Yamuna River; the other follows the Tons River southward to its confluence with the Yamuna. This area is more populated and prosperous than further up the Tons valley, and follows different traditions. Here we find both old temples and new large ones, very ornately designed and decorated.

Mori is the gateway to the kingdom of Mahasu, the most powerful Deity of an area extending as far as adjoining Himachal Pradesh. Mahasu is the chief Deity of the Jaunsar Bawar region (which is in today’s Dehra Dun District, and parts of Uttarkashi), the northernmost district of Uttarakhand. Believed to have arrived here from Kashmir, Mahasu is also worshiped widely in the adjacent state of Himachal Pradesh.

The name Mahasu is used collectively for four brothers: Basik, Pabasik, Bauth and Chalda. Each is regarded as an incarnation or form of Lord Siva. Each has His own temples and territories.

An 11th-century temple at Hanol, on the left bank of the Tons, is dedicated to the most prominent brother, Bautha Mahasu. A protected monument under the control of the Archaeological Survey of India, it is an apt example of Nagar style of architecture. The original temple, a typical structure of stone, was extended later, with three more sections in the front.

The wooden facade has been decorated with three-dimensional figures of Gods and Goddesses, while the ceiling depicts the Navagraha, the nine planets. The temple has four chambers. In the outermost, the drummers play. Women can enter the second chamber and men the third to take darshan of the Deity in the small sanctum sanctorum.

On one side of the third chamber are the murtis of the bodyguards of the four brothers: Kailu Veer for Bautha Mahasu, Kafla Veer for Basik Mahasu, Gudaru Veer for Pabasik Mahasu and Sherkudiya for Chalda Mahasu. Also in this chamber is Gudaru, the bodyguard of the Mahasus’ mother, Dharmakala.

The malis of Mahasu sit on a high platform facing the temple. Hundreds of devotees come to them each day to seek solutions for their problems. Once the Deity enters a mali, he speaks out.

Just a few hundred meters upstream and across the river from Hanol stands the temple of Pabasik Mahasu in Thadiyar village. The outer chambers of this temple have been drastically renovated and repaired with concrete, but the main temple remains intact, retaining its pristine glory with a multitiered pyramid roof and intricate woodwork on side panels.

A couple of miles downstream at Maindrath is the temple of Basik, the second Mahasu. This one faces north, possibly because of lack of space in the area it sits. This three-chambered building has also been renovated with concrete, but still retains some of the original woodwork.

Nine miles downstream from Hanol, the Pabbar merges with the Tons. Following the Pabbar upstream a few miles, we come to the village of Rayagi. Here we find the recently renovated and expanded multi-tiered temple of Sherkudiya Maharaj, bodyguard for Chalda Mahasu. He is the minister of all the Mahasu brothers and is regarded as a Deity in His own right. Devotees come here with problems that have not been solved by their local Deity.

Innumerable mythological figures are carved in this temple, and a tall wooden statue of Hanuman stands on the facade. Four carpenters from Himachal Pradesh worked for five years on the us$34,000 project, according to Prama Nand Sharma, the temple priest. I ask how many wooden temples there are in the region. “Hundreds,” he replies.

We find the fourth brother, Chalda, at the temple in Mohana, a hill station near Chakrata, in the cold, high region between the Tons and Yamuna river valleys. This Deity is moved from village to village in this area over a twelve-year period, staying in each for long durations. He’s been here in Mohana for two years and will soon move to another village. At the end of the twelve years, He goes to the adjoining Himachal Pradesh state for another twelve years.

This is another newly renovated temple. Wooden balconies extend around the basic structure. The drummers live on the ground floor and play music each morning and evening during prayers. They receive donations from the temple, and often have outside jobs as well, tailoring in particular.

The shringar morning ritual typical of most temples in India, in which the Deity is bathed and dressed for the day, is not performed here. A group of people called thani assist the priest during the puja. They ring bells as the priest recites his secret mantras. The priest and the thanis change in a set rotation among those qualified.

Every day the temple is thronged with devotees who come for darshan and to give thanks for blessings received. During our visit, a businessman arrives from Dehra Dun with loads of donations: after 20 years of wedded life, he had been blessed with a son. These Mahasu temples earn a lot of money and have built decent facilities for pilgrims. A few rooms provide overnight lodging, and food is provided from the temple’s community kitchen.

Yamuna River Temples

As we descend from the cold heights of Chakrata toward the Yamuna, we find most temples having two main sanctums or even two separate structures, one for Chalda Mahasu and one for Bautha Mahasu.

The temple in Bishoi is a masterpiece of modern workmanship (see pages 18 and 30). Just finished in 2015, the multi-storied temple faces east, overlooking the Yamuna valley. Ten artisans worked for six and a half years to complete this structure. Built at the site of the original temple, this one has two central parts, some distance apart and made of stone and wood. One is the temple of Chalda and the other that of Bautha. Both are cleverly covered with lavish woodwork in a seamless manner. Long corridors supported by rows of wooden pillars have endless rows of wooden fringes that constantly dangle to produce a magical sound. The walls are covered with large panels carved with figures of various Gods. A row of rooms in front of the temple is equally embellished with woodwork. Altogether, over 2,500 figures and scenes from the Mahabharata and Ramayana are depicted here. The first invitation to any wedding in the area is always sent to the temple, as well as a portion of any new harvest.

Bishoi resident Gyan Singh Chauhan, age 86, explains that the construction cost of $336,000 was borne by the people of the area, and part of the wood was contributed by the state forestry department and local devotees. “Architects from Uttarakashi were brought in to design the temple,” he tells me, “but they were unsuited for the task compared to our own masons and carpenters.”

Downstream on the Yamuna from Bishoi, the tree species are less suitable and long-lasting than the coniferous forests of the higher regions. The Mahasu temples at Lakshyar and Lakhwar have recently been rebuilt with concrete, though a lot of wood is still used in pillars, windows, panels and fringes. The design is still the same, with two temples in one, for Chalda and Bautha Mahasu. Following the tradition of Chalda, the sanctum sanctorum is on the second floor, while the first or ground floor is used for other purposes.

Conclusion

Visiting these wooden edifaces was like going back in time. The faith of people in their Gods and Goddesses has kept the art of temple construction alive. As in the rest of India, every village has its own temple.

But the art and tradition of making these wooden sanctuaries is threatened. Factors include the rapid changes in life-styles, migration of people to cities, shrinking forests, and a ban on felling trees. The adjoining Yamuna valley in the east, and Himachal Pradesh in the west, are home to thousands of unique temples with an amazing diversity of housed.

About the Author

Dev Raj Agarwal of Dehra Dun, India, is a photographer who loves to capture the immense diversity of the people, cultures and nature of India, especially in the Himalayas. He has worked for the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Botanical Survey of India. Email: devrajagarwal@hotmail.com

Additional Photos

Pingback: Today at Kauai's Hindu Monastery

Thank you, Devaraj, for this extraordinary trek into a part of Bharat I had no idea existed.