A Fifteenth Century Poet-Saint Wisdom on Life, Death, Guru & God

By Lakshmi Chandrashekar Subramanian

All photos: Arun Kumar Mishra—Dinodia

“Drop falling in the ocean: everyone knows.

Ocean absorbed in the drop: a rare one knows.”

Kabir, Sakhi 69, Bijak (Hess)

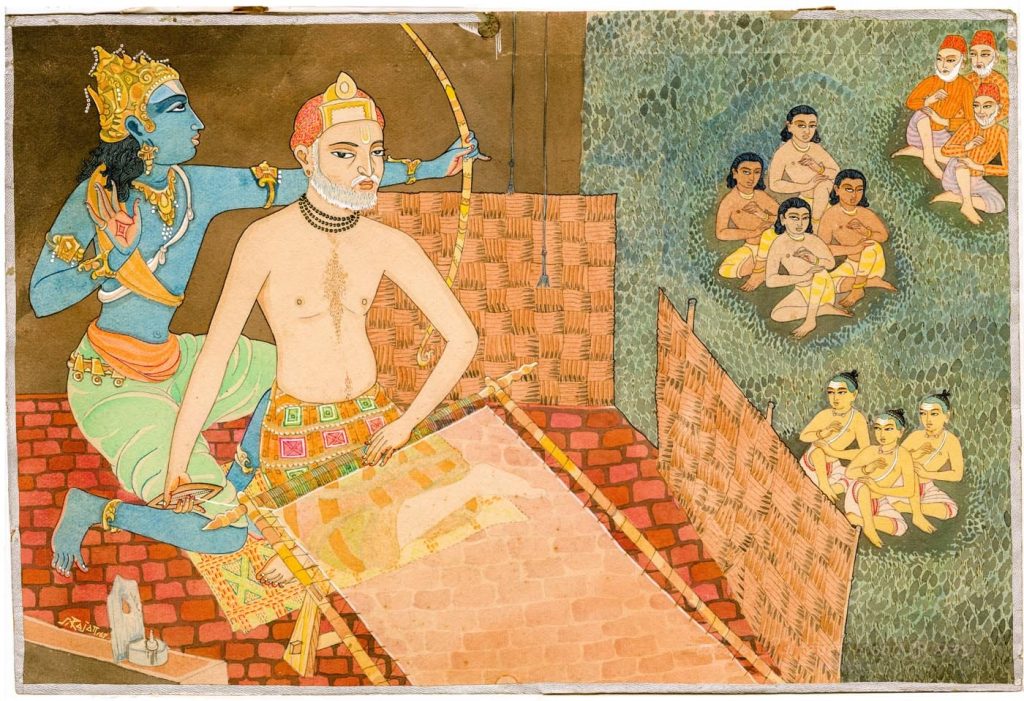

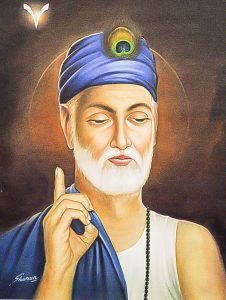

For over five hundred years, Kabir’s poetry has been remembered, recited and sung throughout North India and today in various parts of the world due to the Indian diaspora. Sant Kabir (ca. 1398-1448 or 1518) is one of the most renowned poets of the Indian vernacular languages. Also known as Kabir Das, “servant of the Great (God),” he belonged to the weaver (julaha) class in Varanasi, the ancient city in the present-day Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. Kabir’s works are known for their nirgun bhakti, personal devotion to the formless, impersonal Divine. Recurring themes in his poems include a focus on the name of God, critiques of religious customs, the transience of life, and the spiritual need for a true teacher, or guru. His approach defied convention and questioned orthodoxies, not unlike other luminaries in South India, including Virashaiva poet-saint Basavanna, and contemporaries in the North, like Guru Nanak and Mirabai. Categorized historically, Kabir’s works can be placed outside of the Hindu/Muslim binary, and later influenced the nascent Sikh community. Today various Hindu, Sikh and Sufi communities claim Kabir; and his dohas (couplets) are taught in secular education systems in India and Indian international schools abroad. Kabir’s wisdom is widely invoked through bhajans (devotional song) performed in classical, contemporary and film music scenes. His works are studied in academic circles and even referenced by political groups. The social contexts in which Kabir’s poems were composed and received are relevant, as they were a part of the oral tradition, generally sung or heard rather than silently read. Especially in the case of the Guru Granth Sahib, Kabir’s poems were collected to be sung and are organized in ragas. Kabir composed in a mixed Hindi dialect, often termed karî bolî hindî. The language, content and poetic style contextualize the poet in a larger devotional tradition; his poems fit into the historical backdrop of the bhakti movements that arose in multiple regions and languages throughout India. During this period of several centuries (ca. 500-1700 ce), there was a fervent attempt to make religion accessible to common people regardless of language, gender or social status, with special emphasis on devotionalism expressed in India’s many local languages. To underscore this, A. K. Ramanujan quotes Kabir: “Sanskrit is as the water of a well, but the vernacular (bhashya) [is] like a running brook” (Ramanujan, 1999: p. 330). The Kabir poems we encounter in this educational feature are waters from this brook.

Nirgun Poems: Devotion to the Formless Divine

Kabir’s poems invite us to rethink our ideas of devotion and of God. While affirming some traditional aspects of worship, he decimates others. This epigram draws out two basic aspects of Kabir’s bhakti: all-inclusivity, and God as protector.

So I’m born a weaver, so what?

I’ve got the Lord in my heart.

Kabir: secure in the arms of Ram,

free from every snare.

Adi Granth, sakhi 82; Hawley and Juergensmeyer 2004: p. 58

The first line suggests the non-importance of jati in the world of devotion, and the following two lines underscore the principle. Kabir makes a brazen statement about his profession that denotes jati. His mention of being born a weaver problematizes the idea that one’s birth determines one’s religious status. The indication here is that bhakti is an active choice rather than a matter of birth or legacy; it is something that one has to cultivate. His nonchalant tone conveys a bold stance: bhakti should be accessible to all. But there is a prerequisite, which is to have the lord in one’s heart. Kabir states that as long as one is truly devoted to Ram, he or she is a devotee. The fact that Kabir lived and spoke out against orthodoxy in 15th century Varanasi, where Brahmin priests played a crucial role in society, makes the poet-saint’s provocation all the more powerful.

The second half of the poem demonstrates the fruits of devotion in the form of divine protection. Having God as protector or guardian is a common theme in bhakti literature, and it is this sentiment that is reflected in Kabir’s epigram. Hindu Deities such as Shiva, Vishnu, Durga and Hanuman are known for their protecting disposition, and the list includes Lord Rama. The image in Kabir’s poem of being “secure in the arms of Ram” conveys the notion that once devoted to God, the devotee will be taken care of, “free from every snare.” Kabir’s use of corporeal imagery is intriguing as the “heart” and “arms” indicate the physicality associated with bhakti, as well as the sagun (“with qualities”) nature of God. This reminds us of the body-mind argument raised by the issue of jati in the first half of the epigram, in which Kabir advocates mind over matter, although in this instance, imagery concerning the body is used in a positive context.

Nirgun God

Kabir uses his words to intimate the formless divine that lies beyond words. Nirgun (literally, “without attributes”) names the view that God cannot be positively conceived and should not be worshiped through images or other visual forms (Hawley and Juergensmeyer 2004: p. 230). In this way, God can be interpreted as “the One,” “the All,” and “knowledge without duality,” which is the facet of the Divine that Kabir refers to in the following couplet:

The One is one with the All,

the All is one with the One.

Kabir is one

with the knowledge without duality.

sakhi 272 / Dharwadker 2003: p. 184

Here Kabir states that the One, referring to nirgun God, is the essence that permeates the All in the world of externalities. In his cryptic and laconic style, he emphasizes that it is human beings who have to realize this oneness just like Kabir did. The idea of “knowledge without duality” is indicative of 8th Adi Shankara’s advaita (nondualist) philosophy, in which Brahman (cosmic being) and atman (individual soul) are viewed as one. This is a case where similar ideas that were earlier limited to Sanskrit philosophy are being opened up to people at large through easily accessible languages. This is a key trait of the bhajans of India’s vernacular poet-saints. In other poems Kabir is more direct in his language and style. In a poem from the Kabir Granthavali, he says, “He’s Brahman: unmanifest, unlimited. He permeates everything as absolute knowledge” (Dharwadker 2003: p. 148).

Although we have encountered two poems that conceptualize the Divine in abstract terms, there are other ways that Kabir played with the concept of nirgun. For example, there are two poems in the Adi Granth in which God is personified as the bridegroom who has come to take away his bride, the spiritual seeker, in marriage. Kabir says, “I will walk around the fire with Ram Rai, my soul suffused with His color” and “Ram, my husband, has come to my house,” (Dass 1991: p. 8-9). The poet has used the motif of unity in marriage as an analogy for spiritual unity, an idea that Guru Nanak also adopts in some of his poetry. Although the portrayal of the Divine appears to be sagun (with qualities) in this context, the poetry does not describe specific personality traits or physical form and hence can still be characterized as nirgun in spirit. In addition to demonstrating a novel way in which the nirgun God can be represented, these poems create room for speculation about the intertextuality between the works of Kabir and other poet-saints such as Nanak, wherein Kabir’s poems may have directly influenced Nanak’s works.

Challenging Orthodoxies

Kabir often stressed the shortcomings of established Indian religiosity, usually that of popular Hinduism and Islam. For instance, he mockingly called out to siddhas (Hindu adepts) and pirs (Sufi masters) to expose their hypocrisies. However, one should be wary of interpreting his words as encouraging religious unity between the two faiths, as this was hardly his agenda. Rather than building a bridge between the two, he condemned the follies, rituals and orthodoxies of both—following a facet of nirgun theology that questions all worship of form. Instead of solely criticizing organized traditions, his poetry reflects his personal idea of transcendence of all conventional religious practices. This could be why Kabir is often categorized as a mystic rather than a saint, with the attending religious associations.

In the following poem from the Adi Granth, Kabir not only questions the significance of religious structures, both ideological and physical, but also the role and authority of leaders such as priests (mullah in Persian/Urdu).

Broadcast, O mullah, your merciful call to prayer—

you yourself are a mosque with ten doors.

Make your mind your Mecca, your body the Ka’aba—

your Self itself is the Supreme Master.

In the name of Allah, sacrifice your anger, error, impurity—

chew up your senses, become a patient man.

The lord of the Hindus and Turks is one and the same—

why become a mullah, why become a sheikh?

Kabir says, brother, I’ve gone crazy—

quietly, quietly, like a thief, my mind has slipped into the simple state.

(Adi Granth, Raga Bhairava, shabad 4)

The vivid Islamic imagery in this poem—mullah, call to prayer, mosque, Mecca, Ka’aba, Allah, sheikh—serves as the backdrop for Kabir’s rejection of orthodox practices. In my reading, the crux of the poem is in the second stanza, where Kabir says, “Make your mind your Mecca,” an indication to seek spirituality within rather than in external structures. It suggests that a person’s mind should be pure and serve as the holy place of worship, not to mention that the relevant journey is considered to be more mental than physical. The corporeal imagery carries over to the second line of the stanza and beyond, where the human body is compared to the sacred Ka’aba. This is an extension of “you yourself are a mosque with ten doors.” This can be interpreted as a reference to Hindu theology in which the human body is believed to possess ten faculties (indriyas) at its gross level, consisting of five faculties for action (karma indriyas): grasping, moving, speaking, eliminating and procreating; and five for perception (jnana indriyas): seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting and feeling. These could be the ten doors Kabir is referring to, as the human being is thought of as a building with ten doors in traditional yoga philosophy. Moreover, “your Self itself is the Supreme Master” is likely an indication to the concept of Brahman, and hence Vinay Dharwadker has chosen to capitalize the word “Self” in the English translation. In this poem, Kabir uses the name Allah in suggesting reform. In other poems, he uses the name Ram to appeal to his fellow men to give up base emotions, such as anger, and adopt a more spiritual lifestyle. Given the largely Hindu socio-cultural context of 15th century Varanasi and the hub of Brahmanical orthodoxy that it was, it is evident why Ram was more appealing than Allah, thus explaining Kabir’s choice. The lines “The lord of the Hindus and Turks is one and the same” refer to God as Supreme Master, untainted by sectarian or religious structures. This is a marker of nirgun poetry, in addition to the focus on interiorization (seeking God inward) rather than grosser externalities. The phrase “I’ve gone crazy” in the last stanza is reminiscent of the Sufi concept of wajd (spiritual ecstasy), and it is not surprising that today Sufi qawwali singers almost always include Kabir poetry in their repertoire. The key word in the final line of the poem, “my mind has slipped into the simple state,” is simple. We can interpret Kabir’s words to mean that everything that he has mentioned in the poem is simple, and the practice of religion can be simple as well. The overarching question is: are man-made religious orthodoxies simple? On the other hand, Kabir’s emphasis on craziness could suggest the opposite of simple. The last line could also be tongue in cheek, where Kabir is referring to the naivety of a simplistic outlook.

In confronting the ideas of religious orthodoxy, Kabir draws from the vocabulary of both traditions to communicate his stance: God does not live in temples or mosques, but within one’s own body, mind and soul. But was Kabir a Ram bhakta, since he mentioned Ram in his poems? The poet uses “Ram” as a synonym for Truth or inner experience, and as a goal that one should meditate on and strive toward. Despite not referring directly to the Deity Rama of Ayodhya, the word has strong Hindu connotations.

Praise to the Guru

The necessity to seek guidance from a guru or “true teacher” is underscored in the poetry of Kabir, an ideology parallel to traditional Hindu thought. Kabir’s stance on the role of the teacher is clear in this popular couplet that begins with guru gobind dou khade / kake lagoon pay? His answer is definitive:

Guru and God are before me. Whose feet should I touch?

I offer myself to the guru who showed me God.

(Hess 2015: p.288)

It is significant that guru is the first word in this couplet, and appears even before God, since according to Kabir it is with the guru’s grace that God can be reached. Sometimes God is the perfect guru. He also elevates the status of the guru in poem Aivi aivi sen.

Such signs my true teacher showed me—

it can’t be spoken with the mouth, O sadhu

in my country there’s no ground, no sky

no wind, no water, O sadhu

in my country there’s no moon, no sun

no million stars, O sadhu

in my country there’s no Brahma or Vishnu

no Lord Shiva, O sadhu

in my country there’s no Veda, no Gita

no song, no couplet, O sadhu

in my country there’s no rising or setting,

no birth, no death, O sadhu

Step by step a truth-seeker arrives.

Kabir, a seeker, climbed to nirvana, O sadhu.

(Hess 2015: p.283-4)

Kabir speaks of the greatness of the “true teacher” by stating that what the guru gives, or shows in this case, “can’t be spoken with the mouth.” It is beyond words and necessarily needs introspection. Kabir scholar Linda Hess explains that the concept of guru is both inner and outer. “The reference may be to a human being who gives priceless guidance or to an innate source of knowledge that is always with us” (Hess 2015: p. 288). This is a key facet of nirgun poetry which this poem serves to demonstrate. Kabir refers to key Hindu Deities and texts (Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva, Veda and Gita), and states that the Truth he speaks of is beyond all of them. He dedicates this knowledge to the “true teacher,” thereby eliminating the seeker’s ego. In this case, the seeker is Kabir himself.

Life & Legends

There are two kabirs that we are simultaneously negotiating within our understanding: the Kabir of legend, and the actual man who belonged to early modern times. The latter Kabir, the historical poet-saint, lived in North India at a time when there was political unrest, with the Persian invaders’ rule in decline. Kabir, and Guru Nanak in the following century, were placed well between the Hindu and Muslim communities. Kabir’s home city, Varanasi, was diverse, with people from different jatis, social backgrounds and religious traditions. Based on his poetry and popular tales, we can assume that his words were controversial both for Hindus and Muslims. Kabir was a social critic who spoke against inequality and abuse of power, so we infer that these facets of life were a part of the social climate in his world. But the special interest in Kabir’s socio-political persona has been most evident in the late twentieth century onwards, which serves as a commentary for the pressing issues of that time in history.

As Hess explains in The Bijak of Kabir, having converted to Islam in 15th century North India often meant being half Hindu. “For several centuries the Muslim invaders had been waging warfare up and down the subcontinent, taking over kingdoms and propagating their faith through the points of the sword,” (Hess 1983: p. 5). Thus, people often converted to the rulers’ religion without completely forsaking the beliefs and practices of their former faith. Legend has it that Kabir was no stranger to that oppression, as Sikandar Lodi, ruler of the Delhi Sultanate, made multiple attempts to kill the outspoken poet.

It is safe to say that there was political unrest during Kabir’s time, leading up to the downfall of the Delhi Sultanate and rising of the Mughal empire in 1526. “He was alive at a time when the divisions between Hindu and Muslim were feverish: recent demolitions of sacred sites, and frequent confrontations between Muslim rulers and the Hindu kshatriya communities,” says Brahmachari Vrajvihari Sharan, priest of England’s Edinburgh Hindu Mandir. However, there was also the flourishing of devotional poetry in various regions—Namdev in Maharashtra (14th century), Narasinha Mehta in Gujarat (15th century), Mirabai in Rajasthan (16th century) and Chaitanya Mahaprabhu in Bengal (16th century), to name a few of the renowned Hindu poet-saints. Sufi poetry, then in its ascendency, illumined this era as well. Hess concludes that Kabir’s poetry reflects the rich interplay of religious traditions of that period in history, including but not limited to Hinduism, Buddhist tantrism and the tradition of the Nath yogis.

Manuscripts exist for some of Kabir’s poems, but certainly not all; most poems were transmitted through oral tradition, and later in musical and written form. We are unable to find many reliable or dated early written sources, and this is where the Kabir of legend gains prominence—the memory that was created, accessed and expanded by musicians, traders, travelers and devotees down the centuries in North India. What we have available today was recorded a century after Kabir is believed to have died. These include well-documented manuscripts of the Sikh scriptures Adi Granth and Goindval Pothis, the Kabir Granthavali of the Dadu Panth, and the Bijak of the Kabir Panthis. Written biographical narratives about Kabir’s life include Anantadas’s Kabir Parchai, composed around 1625, and Bhaktirasabodhini by Priyadas, composed around 1712. Both biographers placed Kabir into a rigidly sectarian model of Sagun Vaishnavism (Dharwadker 2003: p. 20). Subsequently, a different set of birth stories originated from the Kabir Panth (organized community of Kabir followers), which even today portrays Kabir as a divine child born under miraculous circumstances.

It is impossible that Kabir composed every poem attributed to him. We thus come to terms with the realities of collective authorship: Kabir as the idealized songster whose body of poetry has been amplified by those who have heard, received, performed and added their own works—something John Stratton Hawley outlines in his book A Storm of Songs (2015).

Another point to note is the difference between authorship and authority. In Three Bhakti Voices (Mirabai, Surdas and Kabir in Their Times and Ours), Hawley asserts that authorship is secondarily relevant, since the manuscript sources we have today are scarce. Instead, it is the poet’s authority—whether it is Kabir’s characteristic signature, “kahat kabir suno bhai sadho,” or stylistic particularities—that counts most in the scholarly engagement with his poetry.

Legendary narratives are situated somewhere between history and myth, and embody the characteristics of both (Lorenzen 2006: p.102). This holds true for Kabir legends, which have been retold and rewritten numerous times over the centuries. Anantadas’s Kabir Parchai contains the earliest hagiographical account of his life; Priyadas retold some of those legends in his 1712 work. There are also many narratives, not mentioned in the Kabir Parchai, that have emerged from the Kabir Panth. Other sources for Kabir legends include the Bhaktavijay, written in Marathi by Mahipati in 1762, narratives from the Dadu Panth, and some Persian accounts. Today, David Lorenzen’s Kabir Legends (1991) is the one of the most comprehensive compilations of these narratives, and serves as a primary resource for this article.

Among the popular stories propagated by the Kabir Panth, the poet’s birth narrative tells us how Neeru and Neema, who belonged to a weaver community, found the infant Kabir at the Lahartara pond and thereafter raised him as their own child.

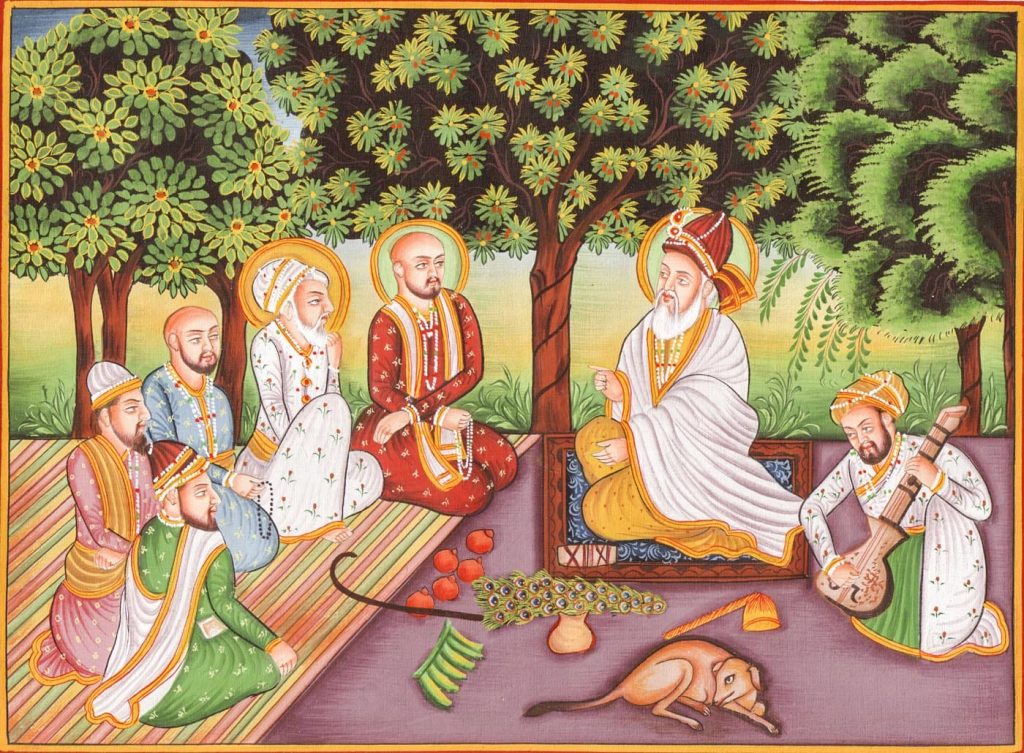

Perhaps Kabir could be seen as his own poet-saint rather than linked with any guru, but he is widely known to be a disciple of the famous Saint Ramananda of Kashi, founder of the Ramanandi order. Ostensibly, this is supported by his mention of Ramananda in the Bijak, sabda 77 (thought to be the only reference to his guru in Kabir’s poetry): “One builds great hopes of himself; but none has found the secret of Hari. Where can the senses find rest? Where has he gone, whom men call Rama ? Where are they gone that were wise? After death they were absorbed in the song. Ramananda drank deep of the juice of Rama. Says Kabir, I am weary with repeating this” (The Bijak of Kabir, Translated Into English, Rev. Ahmad Shah, 1917). However, today’s scholars tend to interpret the word Ramananda in this verse as “the bliss of Rama.” For example: “Many hoped but no one found Hari’s heart. Where do the senses rest? Where do the Ram-chanters go? Where do the bright ones go? Corpses: all gone to the same place. Drunk on the juice of Ram’s bliss, Kabir says, I’ve said and I’ve said. I’m tired of saying” (Hess: 1983, p. 68).

As per legend, Kabir desired for Ramananda, an orthodox brahmin, to be his teacher. However, Kabir feared that he wouldn’t be accepted as he hailed from a humble community of Muslim weavers. Thus, one day at predawn, when Ramananda was on his way to bathe in the Ganges, Kabir lay stretched across the stairs blocking the guru’s way. Ramananda tripped over Kabir in the dark and exclaimed his mantra “Ram! Ram!” and Kabir took the encounter as his initiation. Whether or not this story is historically accurate, Kabir’s poems are full of the Ram mantra. Kabir also probably knew other nirgun poet-saints, such as Raidas, who was also believed to be a disciple of Saint Ramananda. By some accounts, Kabir had a wife and a son, though many, including those of the Kabir Panth, maintain that he was never married and lived a celibate. Kabir Panth sources also contain many travel accounts of Kabir not found elsewhere, including a purported meeting with Guru Nanak.

Saint Ramananda belonged to the Vaishnava tradition. In an article to be published later this year, John Stratton Hawley asks—to quote his title line—“Can There Be a Vaishnava Kabir?” He responds thus: “Certainly the scribe of Fatehpur thought so. All except two of the fourteen Kabir-signed poems in this earliest firmly dated manuscript give God a Vaishnava name (especially Ram), and I’d argue that it hovers over more.” He refers to the widespread use of the names Ram and Hari in Rajasthani and Punjabi collections of Kabir’s poetry, and expresses the view that while in North America it is the Kabir of the Bijak who has triumphed, other early collections of Kabir’s poetry bring out a different flavor. Hawley concludes, “All across the various traditions of reception that give us the Kabir we ‘know’ today, Kabir was in significant measure a Vaishnava—a Vaishnava of the sort I have called ‘vulgate.’ This was the world he lived and breathed, whether he was heard and collected by Kabirpanthis, Dadupanthis, Sikhs or Vaishnavas of the Fatehpur sort.”

A famous encounter between Kabir and Sultan Sikandar Lodi, ruler of the Delhi Sultanate, is an oft-quoted legend. Anantadas’s Parchai describes how all the orthodox members of the community—including mullahs, Brahmins and even Kabir’s own mother—complained to Sikandar about Kabir’s provocative philosophy and activities. Upon being summoned and questioned, Kabir announced his faith in Ram. This so infuriated Sikandar that he ordered that Kabir be chained and thrown in the Ganges. But when the rebel was tossed into the water, the chains broke away and he floated unharmed. In the next ordeal they tied him to firewood and lit him up; but the flames burned as cool as water. Then he was to be trampled to death by a wild elephant, but the pachyderm refused to attack him. Having witnessed all this, Sikandar accepted Kabir’s innocence and rewarded him with riches, which the saint refused, returning home.

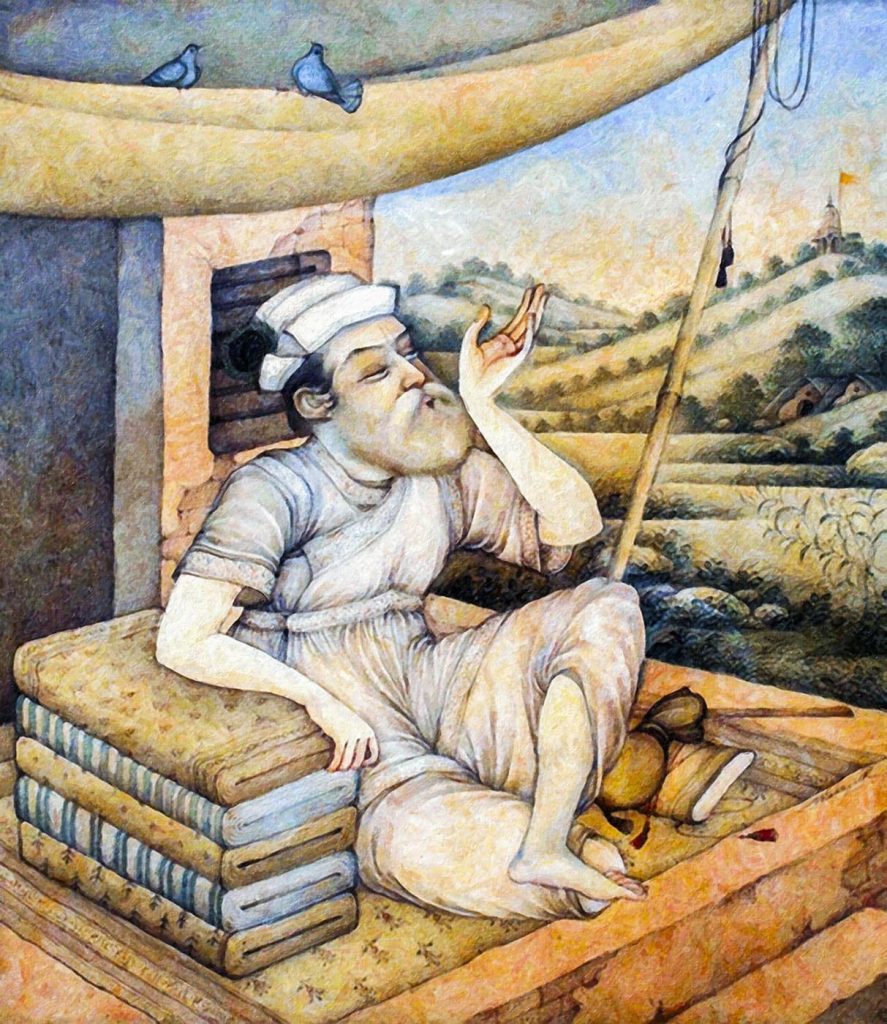

In his final days, Kabir moved from Varanasi to Maghar, a Muslim weavers’ town near Gorakhpur district close to the Nepalese border. When he died there, legend has it that his followers, Hindus and Muslims, argued over how to conduct the final rites; each group wanting to follow its own customs. They agreed that, regardless, the body should be covered in flowers, which they did. Returning later, the corpse had disappeared and only the flowers remained. The Hindus cremated one portion of the blossoms, and the Muslims buried another. Anantadas ends his retelling of this story with Kabir’s being invited into heaven by gods and sages. Today there is a samadhi shrine at the Kabir Chaura in Varanasi and another at Maghar which thousands of followers visit every year to remember and honor the revered poet-saint.

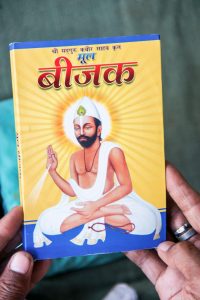

The Kabir Lineage & Institutions

The two kabir maths in varanasi, as well as those in other cities in India, are facilities through which the poet-saint’s teachings are kept alive and current, with dedicated spaces and committed monks and leaders who spread Kabir’s messages to people today. These centers are run by Kabir Panthis, a religious sect of Kabir followers who attempt to live the social and religious ideology embodied in his teachings. They are strict vegetarians and refrain from alcohol, and often tobacco. The Kabir Panth traces its lineage back to Kabir himself. According to Kabir Panthi lore, four of Kabir’s direct disciples founded four distinct branches of the Panth, with Shruti Gopal Saheb establishing the Kabir Chaura Math (considered the mul gaddi, original seat) in Varanasi, with others in Madhya Pradesh and Bihar. Today the Kabir Panth is a large fellowship, with various branches and sub-sects, which do not always see eye to eye, except when it comes to revering the Bijak, which they all regard as their primary scripture. The Bijak, an anthology of Kabir’s verses compiled in Eastern Uttar Pradesh and/or Bihar, is one of Kabir’s most influential works.

The largest Kabir math in Varanasi is built around Kabir’s legendary place of origin, including the famous pond at Lahartara where the infant Kabir was found. The Kabir Math Lahartara houses the senior monks and hosts grand events every year. The second Kabir math is Kabir Chaura, regarded as the official headquarters of the Kabir Panthis. The current head of the Kabir Chaura Math is Acharya Vivek Das, the 24th teacher in the lineage (kabirchaura.com/index.htm). This math houses the Bijak Mandir, a name apt for a temple dedicated to Kabir.

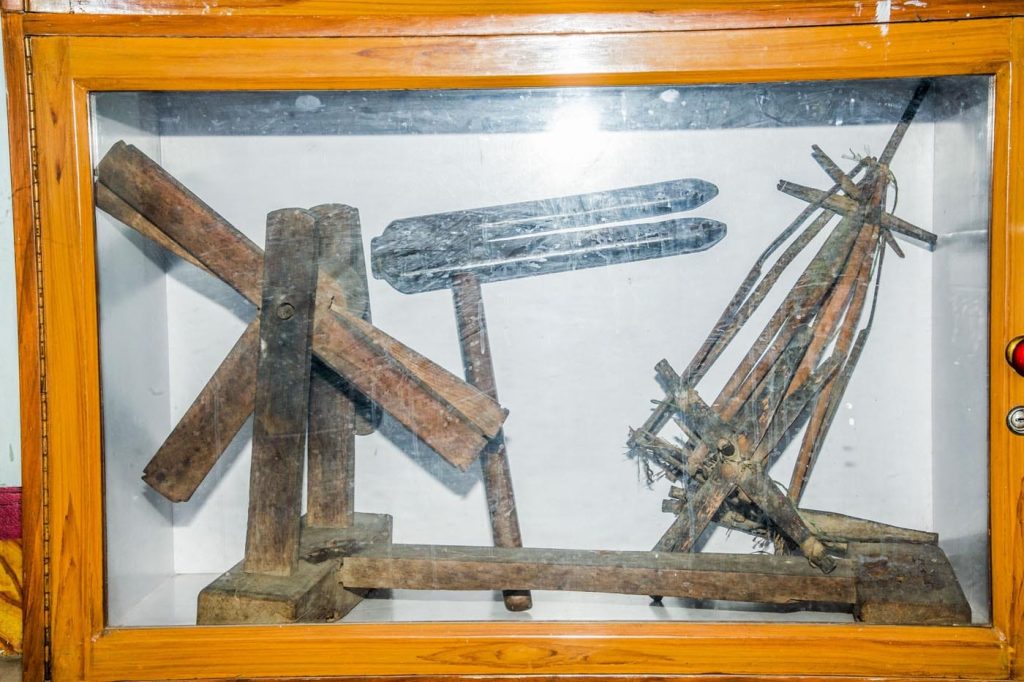

There are various personal artifacts displayed at the Kabir Chaura Math, which the Panth considers to have been Kabir’s own. One such item is Kabir’s khadau (sandals), and others include the mala his guru, Swami Ramananda, is said to have given him, and his weaving machine, all of which visitors can see. There are also many spaces to visit within the kabir maths. These include the Lahartara pond, Samadhi Mandir, Kabir hut, Neeru Teela (Neeru Hill) and the Sadguru Kabir Pustakalaya (library), which holds selected manuscripts of the works on Kabir and other saints.

Each of these places is associated with a popular Kabir legend, may it be Kabir’s birth narrative at the Lahartara pond or the story of Neeru and Neema (the Muslim weavers who brought Kabir up) with the Neeru Teela, where the adoptive parents’ remains are buried.

Today, in addition to being a site frequented by tourists, pilgrims, and Kabir enthusiasts, the maths remain active as places of learning. The Kabir Chaura Math propagates Kabir’s philosophy via publications by its in-house press Kabirvani Prakashan Kendra, as well as through acharyas giving lectures and performing bhajans of the poet-saint. Visitors are encouraged to meditate, surround themselves in nature, and reflect on Kabir’s verses at the maths.

The material structure of the Kabir Chaura Math, with its many spaces including kabir ka ghar (Kabir’s home), physicalizes the significance and remembrance of this poet-saint. Kabir Jayanti (birthday of Kabir) is celebrated every year as a central festival, and attended by several followers of Kabir.

In addition to celebrating Kabir, his life and works, the Kabir Chaura Math also glorifies those who followed his teachings, respected him or otherwise showed commitment to Kabir. For example, among more than a dozen life-size bronzes, there is a statue of Shruti Gopal Saheb, formerly known as Sarvanand, a Brahmin pandit from South India. Despite visiting Kabir to prove his intelligence, he eventually became Kabir’s disciple and is believed to have been appointed by Kabir to lead the Kabir Panth in Varanasi. There is also a bronze of Gandhi at Kabir Chaura, which commemorates his visit to the Math in 1934. These statues of devotees and followers are displayed alongside kiosk signs sharing the history and stories with visitors. One source claims there are nine million adherents to the Kabir Panth.

A Beloved Rascal

The poetry of kabir transcends the orthodoxies of the religious traditions that claim the mystic as their own today. Practices that he challenged include undertaking pilgrimage, visiting places of worship and engaging in ritualistic prayer. Kabir’s focus instead is on popular, practical wisdom, infused with nirgun ideas of guru, God, life and death. He grabs his listeners’ attention through enigmatic questions and riddles. Perhaps this is what makes his verses appeal to diverse groups of people—from religious leaders to academics, Indian classical musicians to folk singers, school children to rickshaw walas. Other religious figures, including the Sikh Guru Nanak and poet-saint Ravidas (also known as Raidas), regarded themselves as belonging to the same family of bhakti poets, and we can see thematic parallels in their poetry.

Kabir is often categorized as a “sant” (saint/seeker of Truth) rather than a “bhakta” (devotee/lover of God), because he conceptualizes Divinity without attributes or personality traits (Hawley and Juergensmeyer 2004: p. 4-5). This differentiates Kabir and Ravidas from bhaktas like Surdas and Tulsidas, who sang about the qualities of Krishna and Rama. Other facets of Kabir’s poetry, such as the rejection of organized religion and emphasis on yoga and primordial sound, also make him relevant in today’s trending “spiritual but not religious” (SBNR) landscape.

Popular media has greatly assisted in spreading Kabir’s messages in this century. Numerous films and documentaries have been made in the last decade; Shabnam Virmani’s four films as part of the Kabir Project are especially noteworthy (www.kabirproject.org). There are annual Kabir festivals held in India and abroad. The Kabir Festival Mumbai (thekabirfest.com) is one of the most happening. It brings together singers, dancers, storytellers and filmmakers to share Kabir’s works through the arts. The 15th century poet-saint even has a Bollywood presence! In Dulhan Hum Le Jayenge (2000), Salman Khan and Karishma Kapoor quote Kabir dohas in their dialogue. In Highway (2014), A.R. Rahman’s song “Heera” is a collection of three dohas, all describing a worthy diamond. Other creative projects, such as Indian-American composer Aks’s Kahat Kabira (2014), have also been inspired by Kabir. It is an album of nine songs that sets his poetry to electronic dance music. In fact, the poet-saint now resides in the palms of our hands in smartphones and other handheld devices; a quick search for “kabir” on YouTube fetches over 600,000 results with dohas, bhajans and documentaries.

Champion of the Downtrodden

By Dr. Rajani Kant, Director/General Secretary

Human Welfare Association, Varanasi

The words of kabir relate most directly to the common man, the disadvantaged section of society, the marginalized communities that face struggles and discrimination based on financial status, jati, creed and gender. He demonstrates in his poetry a revolutionary attitude toward the rulers of his society in favor of the common community.

Sant Kabir has several times said that God is much closer to the poorest of the poor, who are open-hearted, honest and dedicated towards their life, than to so-called religious people who have created the myth that only they can afford God’s blessings through their resources. His dedication to uplifting the poor and the humble relates directly to the social service work to which my life is devoted. His attitudes in this regard stem from his own early life, growing up in a community of poor handloom weavers. He spoke boldly against the religious orthodoxy of his day, preaching respect for everyone, without discrimination, and arguing that all places are equally holy if your heart is transparent, open, sensitive and service oriented.

Kabir’s Way with Words

Kabir’s words were primarily in two literary genres: rhymed couplets (known as doha, sakhi or shalok) and lyric poems (shabda, shabad, pad or bhajan), in addition to the ramaini and folk song forms. The lyric poems, commonly known as bhajans, vary in meter and are usually six to eighteen lines in length, while the couplets are comprised of four half-lines (Hess 1987: p. 113). These forms are placed in separate sections in written compilations such as the Bijak, but are fluidly presented in oral performative contexts. For example, a bhajan is oftentimes preceded by a thematically related doha or a string of dohas. The meter and melody of the couplet is often different from that of the main song. Additionally, the singer has the poetic license to repeat certain words or phrases, instilling additional layers of meaning and emotionality in the listeners’ hearts. A literary device often found in Kabir’s poetry is repetition with variation, and this can appear as a series of negations, repeated words, or grammatical structures. Hess, in The Bijak of Kabir, makes an insightful comment about how, while other bhakti poets such as Mirabai, Surdas and Tulsidas address most of their poems to God, Kabir addresses his words directly to us. This gives rise to the art of the rhetoric, using language to engage, affect and awaken people. Kabir’s verses are filled with verbs and calls to action, tucked into extended metaphors, compelling arguments, dialogues and monologues (1983: p. 9-15).

Good translations allow non-Hindi speakers to appreciate the genius of his poems. A common rule when translating is that the smallest element of translation may not be a word, but a phrase, sentence or even paragraph, as there is much more than literal meaning to communicate. The most famous English translations of Kabir’s poems were, until in more recent decades, those of Rabindranath Tagore published in 1915. Later, in 1976, American poet Robert Bly published newer versions of Tagore’s translations. Both of these are still talked about, though we have more contemporary and arguably better English translations today; most notably those by Kabir expert and Stanford University professor Linda Hess. Her renderings pay close attention to meaning, structure, as well as the orality that is the backbone for all of his words. Hess’s books, articles and intuitive translations have served as a foundation for this educational insight.

Kabir was a master of language, evidenced by the way he used powerful words to communicate the subtlest of ideas in the most blatant way. He was a fierce social critic and iconoclast who probed and questioned, challenged and exposed, and ultimately jolted his audience into facing the many truths of life and death. This was the case especially in the Bijak, as the other two major manuscripts with Kabir’s works, Guru Granth from Punjab and Panchvani from Rajasthan, contain more bhakti-oriented (Vaishnava, in this instance) sentiments and language (Hess 1987: p.117). Kabir’s poetry most often includes an element of ridicule that makes his words not only poignant but also highly provocative. More often than not, the opening line would grab a listener’s attention:

Hindus, Muslims,

both deluded, always fighting.

Yogis, sheikhs, wandering Jains,

all of them lost in greed.

(Hess 2015: p.294)

Kabir’s language was at times so biting that the Sikhs did not include those portions in their texts. At an earlier stage, some poems were considered in line with Nanak’s teachings, but were later viewed as too problematic with the evolution of the Sikh tradition. The Guru Granth consists of hymns of the Sikh gurus, as well as works of Hindu and Muslim saints, including Kabir. Of all the bhagats and Sufis whose works were included, Kabir’s contribution was the largest, with 541 poems (Dass 1991: p.7). Hess refers to the fascinating work of Gurinder Singh Mann, who found that two Kabir poems were included in the Kartarpur Pothis (1604),but later marked as “useless” and excluded from the Adi Granth. She explains, “Both were ulatbamsi, “upside-down language” poems with outrageous, nonsensical, sometimes shocking imagery” (Hess 2015: p.141). His ulatbamsi poems belonged to a long-standing Indian poetic tradition that expressed concepts in bizarre forms but served as rhetorical and teaching devices, though it was certainly not everyone’s cup of tea.

Couplets from the Bījak

If you know you’re alive,

find the essence of life.

Life is the sort of guest

you don’t meet twice. 10

The three worlds are a cage,

virtue and vice a net.

Every creature is the prey,

and one hunter:

Death. 19

Color is born of color.

I see all colors one.

What color is a living creature?

Solve it if you can. 24

Who recognizes Ram’s name,

the bars of his cage grow thin.

Sleep doesn’t come to his eyes,

meat doesn’t jell on his limbs. 54

The best of all true things

is a true heart.

Without truth no happiness,

though you try

a million tricks. 64

So what if you dropped illusion?

You didn’t drop your pride.

Pride has fooled the best sages,

pride devours all. 140

The mind: a mad killer-elephant.

The mind’s desires: hawks.

They can’t be stopped by chants or charts.

When they like, they swoop and eat. 145

From good company, joy.

From bad company, grief.

Kabir says, go where you can find

company of your own kind. 208

Three men went on pilgrimage,

jumpy minds and thieving hearts.

Not one sin was taken away;

they piled up nine tons more. 214

Do one thing completely, all is done;

try to do all, you lose the one.

To get your fill of flowers and fruit,

water the root. 273

A sweet word is a healing herb,

a bitter word is an arrow.

Entering by the door of the ear

it tears through the whole body. 301

If you’re true, a curse can’t reach you

and death can’t eat you.

Walking from truth to truth,

what can destroy you? 308

Dying, dying, the world keeps dying,

but none knows how to die.

No one dies in such a way

that he won’t die again. 324

Source/references:

Hess, Linda, and Sukhdev Singh. The Bijak of Kabir. San Francisco: North Point, 1983.

Popular Bhajans

Jhīnī jhīnī bīnī chadariyā

Subtle, subtle, subtle is the weave of that cloth.

What is the warp

what is the weft

with what thread

did he weave

that cloth?

Right and left

are warp and weft

with the thread at the centre

he wove that cloth

The spinning wheel whirled

eight lotuses, five elements,

three qualities, he wove

that cloth

It took ten months

to finish the stitching

thok! thok! he wove

that cloth

Gods, sages, humans wrapped

the cloth around them

they wrapped it

and got it dirty

that cloth

Kabir wrapped it with such care

that it stayed just as it was

at the start, that cloth.

Subtle, subtle, subtle

is the weave of that cloth.

Tū kā tū

You, only you

Hey wise wanderer, what’s the secret?

Just live your life well.

In this world, flowers, branches—

wherever I look,

you, only you.

An elephant is you

in elephant form,

an ant is just a little you. As elephant driver

you sit on top. The one who drives

is you, only you.

With thieves you become a thief,

you’re among the outlaws too.

You rob someone and run away.

The cop who nabs the thief is you,

only you.

With givers you become a giver,

you’re among the paupers too.

As a beggar you go begging.

The donor is you, only you.

In man and woman

you shine the same,

Who in this world

would call them two?

A baby arrives and starts to cry.

The babysitter is you, only you.

In earth, ocean,

every creature, you alone

shine forth. Wherever I look, only you.

Kabir says, listen seekers,

You’ve found the guru

right here, right now!

Sākhīya vā ghar sab se nyārā

O friend, that house is utterly other where he lives, my man, my complete one.

There’s no grief or joy,

no truth or lie,

no field of good and evil.

There’s no moon or sun,

no day or night,

but brilliance

without light.

No wisdom, no meditation,

no recitation, no renunciation,

no Veda, Quran,

or sacred song.

Action, possession, social

convention, all gone.

There’s no ground, no space,

no in, no out, nothing like

body or cosmos,

no five elements, no

three qualities,

no lyrics, no couplets.

No root, flower, seed, creeper.

Fruit shines

without a tree.

No inhale, exhale, upward, downward,

no way to count

breaths.

Where that one lives,

there’s nothing.

Kabir says, I’ve got it!

If you catch my hint, you find

the same place—

no place.

Source/references:

Hess, Linda. Bodies of Song: Kabir Oral Traditions and Performative Worlds in Northern India. New York: Oxford UP, 2015.

Hess, Linda. Singing Emptiness: Kumar Gandharva Performs the Poetry of Kabir, p. 60-101. London: Seagull, 2009.

Poet’s Praise

“Singing Kabir is always an uplifting experience. Kabir, the no-nonsense mystic poet, talks of yoga (awakening of the kundalini) as the only way to reach God/higher planes of existence. His singular message of looking inwards and finding the entire universe there is timeless. I no longer feel compelled to enter big temples or other such holy places, which have become commercial business hubs under the garb of religion. Kabir’s message of doing away with discrimination of all kinds is still relevant today in an era rife with religious-social hatred and global terrorism. Kabir brings me peace and hope. He is a guiding light for my spiritual journey.”

Pushkar Lele, Hindustani classical vocalist who specializes in Kabir and sings in the style of the legendary Kumar Gandharva

(www.pushkarlele.com)

“To me, Kabir’s appeal comes from the fact that you cannot place a finger on his affiliation with just one religious tradition. He personifies the nature of life, with its lack of clearly defined boundaries. Today we live in a world where people function as fluid entities more than ever before, and in this current context his appeal is great. From a musical standpoint, he speaks to that part of my identity that seeks to create outside borders. His ideology complements artistic identities that incorporate a myriad of influences.”

Aks (Ashwin Subramanian), Indian-American composer and vocalist who features Kabir extensively in his albums and live shows of contemporary devotional music (www.akscomposer.com)

Bibliography & Acknowledgements

Dass, Nirmal. Songs of Kabir from the Adi Granth. Albany: State U of New York, 1991.

Dharwadker, Vinay. Kabir: The Weaver’s Songs. New Delhi, India: Penguin, 2003.

Hawley, John Stratton, and Mark Juergensmeyer. Songs of the Saints of India. New York: Oxford UP, 2004.

Hawley, John Stratton. Three Bhakti Voices: Mirabai, Surdas, and Kabir in Their Time and Ours. New Delhi: Oxford UP, 2005.

Hess, Linda. Bodies of Song: Kabir Oral Traditions and Performative Worlds in Northern India. New York: Oxford UP, 2015.

Hess, Linda. Singing Emptiness: Kumar Gandharva Performs the Poetry of Kabir. London: Seagull, 2009.

Hess, Linda. Three Kabir Collections: A Comparative Study. The Sants: Studies in a Devotional Tradition of India. Ed. Karine Schomer and W. H. McLeod. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Religious Studies Series, 1987.

Hess, Linda, and Sukhdev Singh. The Bijak of Kabir. San Francisco: North Point, 1983.

Keay, Frank Ernest. Kabir and His Followers. Calcutta: Association (Y.M.C.A.), 1931.

Lorenzen, David N. Kabir Legends and Ananta-das’s Kabir Parachai. Albany: State U of New York, 1991.

Lorenzen, David. The Kabir Panth. The Sants: Studies in a Devotional Tradition of India. Ed. Karine Schomer and W. H. McLeod. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Religious Studies Series, 1987: 281-304.

Lorenzen, David N. “The Life of Kabir in Legend” Who Invented Hinduism: Essays on Religion in History. New Delhi: Yoda, 2006.

Ramanujan, A. K. The Collected Essays of A.K. Ramanujan.

Vaudeville, Charlotte, and Harry B. Partin. “Kabir and Interior Religion.” History of Religions 3.2 (1964): 191-201.

Special Acknowledgement: Dr. Rajani Kant Director/General Secretary Human Welfare Association, Varanasi (www.hwavaranasi.in),

was instrumental in our photo shoot at the two Kabir maths in Varanasi.

Where to Place Kabir?

An Interview with Professor John Stratton Hawley, Barnard College, Columbia University, New York, Conducted by Archana Nagarajan

What is your take on kabir’s hinduness? The Sikhs claim him, the Muslims also. While his God certainly transcends the proprietary claims of faiths, it seems to us he stood most firmly on Hindu soil. Would you comment?

JH: One of the striking things about Kabir is that in a certain cluster of very well-known poems he sets Hindus and Muslims opposite to one another, rhetorically speaking—what the qazi does wrong and what the pundit does wrong. And those “wrongs” look an awful lot alike. So I find it pretty hard to locate Kabir as standing on either side of the fence. What he’s really saying is: There is no fence! Or if you think there is a fence, well, I don’t care about it very much.

You mention the Sikhs. We have a story about how Kabir met Baba Nanak in Banaras—a great story, but I’m skeptical that any such meeting happened in historical time. Certainly we don’t have anything in Kabir’s poetry that reveals an awareness of Sikh teaching as such. And yet it’s crucially important that the Sikhs were among the first to collect Kabir’s poems and set them down on paper—in 1604 in the Kartarpur Bir, which formed the backbone of the Guru Granth. He also appears in the Goindval Pothis, which may have been composed as early as the 1570s, though we have no dated manuscripts. That’s early! If what would make Kabir Hindu is that Hindus have embraced him—which by all means they have—then we’d have to make him Sikh by the same token.

So I’m worried about calling Kabir Hindu or Sikh—or Muslim, for that matter. I think he would rebel. But what about Vaishnava? There you could make a case. Maybe you think of that as a subset of “Hindu,” but as it relates to Kabir, I wonder. At least, I don’t think that’s how he thought about things.

Think of all those poems where he intones the name of Ram. There’s nothing in his poetry to suggest that he cares at all about the Ramayana—he never tells any part of that story, so far as I know—and yet: Ram! Ram as the name of the place where Kabir takes refuge. I’ve just been putting together an essay entitled “Can There Be a Vaishnava Kabir?” In the end I think we have to say yes to that. How can we not? There are poems in the first dated text that gives us access to Kabir—the 1582 anthology from Fatehpur, which especially features Surdas—and they just don’t make sense if you try to get rid of the names of Krishna that appear there, Madhav or Banvari. If these poems belong to Kabir—and I can’t see how we can cast them out—then he has to be a Vaishnava.

But what is this Vaishnavism? It’s a sort of “vulgate” Vaishnavism—a very big-tent Vaishnavism. It makes us stand outside the yard that we usually think of as being bounded by a Vaishnava fence. That’s where Kabir’s Ram is: beyond any fence.

So is Kabir Hindu? I guess I’d like to turn that question on its head. I’d ask not whether Kabir fits the Hindu mold, but whether we can think of Hinduism in somewhat different terms than we usually do. This kind of Hinduism would have to be a religion eager to embrace Kabir without denying that Muslims and Sikhs have a perfect right to do so at the same time.

AR: Professor, you know Hindi and have encountered his works more directly than most of our readers will be able to. How would you characterize his vernacular? Was he a Shakespeare? An Omar Khayam? A Kahil Gibran? Please compare his linguistic style with poets and songwriters we know.

JH: Well I’ll tell you what comes to mind: Bob Dylan! I guess it’s the contrarian voice, and the way Dylan undermined what counted as music in his time. And you know what? People couldn’t get Dylan’s music out of their heads—just like Kabir. But you could go farther—the Beatles, maybe, or Chuang Tzu, or Luther. And we better not forget about the American poets who have been so eager to take on Kabir themselves—Robert Bly in our own time, and earlier, Ezra Pound.

AR: How would you connect the poet with the bhakti movement?

JH: If Kabir is part of what we call the bhakti movement, it’s only because that idea has been fashioned in significant part precisely to make him so. I’ve tried to make that case in my recent book A Storm of Songs. I love it that we look back and try to find analogies between aspects of Kabir and what we find in much earlier South Indian bhakti poetry. But I doubt there’s a real lineage there, certainly not one that got passed from guru to pupil through the ages.

And the idea that bhakti might just be the groundwork for higher self-realization? Oh man, would Kabir have a few things to say about the conceits built into that one! I think he would have rejected it out of hand.

AR: Does the bhakti of Kabir allow for a pure non-dual perception of the cosmos? Can his God be All and in all? Is his God all-pervasive? Is his God transcendent as well as immanent?

JH: Yes to all of that. But I wonder whether Kabir would have liked the self-ascribed purity that your question seems to imply—“pure non-dual perception.” He did seem to hold himself up as an example of what he was trying to get across—he talked out of his own experience—but I don’t think it was because he thought he was purer than anybody else. More non-dual than thou? I don’t think so.

AR: Kabir has been heavily criticized for his depiction of women. Most say that he deemed them contemptuous and the main reason for male sin. Yet, there a disparity in his writing when he goes from this: “Woman ruins everything when she comes near man; Devotion, liberation, and divine knowledge no longer enter his soul;” to actually taking up a female persona: “My body and my mind are in depression because you are not with me. Then what is this love of mine? The bride wants her lover as much as a thirsty man wants water.” Can you comment?

JH: You’ve put your finger directly on one of the great Kabir debates. Purushottam Agrawal has been eloquent in trying to explain how we can live with this disparity, and Linda Hess no less so. It’s a big job, but I love this debate because it keeps us honest. It keeps us from deifying Kabir—or at least granting him sainthood. It makes us aware that he was a man of his times: how could he not be? And maybe it helps us feel a little more comfortable with the unruly paradoxes of sexuality that continue to confront us all.

AR: Given Kabir’s contribution to the bhakti movement, would you say that his view on women would be a good representation of that of the movement? The Bhakti movement strived for equality and attempted to ignore the jati system, was this of any benefit to women at all?

JH: Well, I guess I have to confess right off the bat that I’ve recently spilled a few words trying to call into question the historical reality of the very bhakti movement you’ve just affirmed. It’s my Storm of Songs again. But never mind. Speaking of Kabir’s own time, the sixteenth century, Mirabai comes to mind. Now there clearly is a figure who’s come to serve as an example of how bhakti can be liberating for women—I mean, some women have felt that. Others have not. But in any case we have to remember that there is only a single poem of Mira’s that can be firmly dated to the sixteenth century, her own. One! So who is this Mira we’re talking about? Yes, her story was being told even then, and already in different ways, but who was she?

With Kabir it’s much clearer. Here we have a flood of words that were remembered as his own in the sixteenth century itself. Some of them, we know, concern women—either to fend them off or to embrace what they stand for. But when Nabhadas praises Kabir in his Bhaktamal, we don’t hear about any of that.

AR: Would you like to add anything that we haven’t already talked about that you think is important with regard to Kabir?

JH: I can hear Kabir trying to shut me up.