Exploring India’s Miniature Painting Tradition

Our Chandigarh artist reveals the tremendous teamwork and discipline needed to create the miniatures that have enchanted the world for centuries

By Baani Sukhon

Indian miniature paintings are a study in perfection. Each work, on a small canvas or other painting surface, is rich in composition, vibrantly colorful, and depicts a story to the fullest. The paintings typically feature lush landscapes, graceful forms and stylized figures.

This is an art genre that entails intricate brushwork, great expertise in craftsmanship and the mastery of many different techniques. As such, one painting will represent the work of specialists in several fields—not only what we usually consider as “art” (composition, color and so forth) but also the creation of the painting surface itself and the many natural pigments, as well as each of the many steps between the initial sketch and the finished masterpiece.

These paintings originated not as independent pieces but rather as narratives or illustrations for manuscripts or books. The tradition bloomed primarily as a means to reveal the Divine. It gained momentum with the revival of Vaishnavism and the growth of the Bhakti Movement in the 18th century. Devotional literature like Gita Govinda, Bhagvat Purana and Surasagara became the source of inspiration for the Indian artists. Even the paintings commissioned by the Hindu princely courts were an act of respecting the sacred scripts and religious epics.

Diverse Styles and Themes

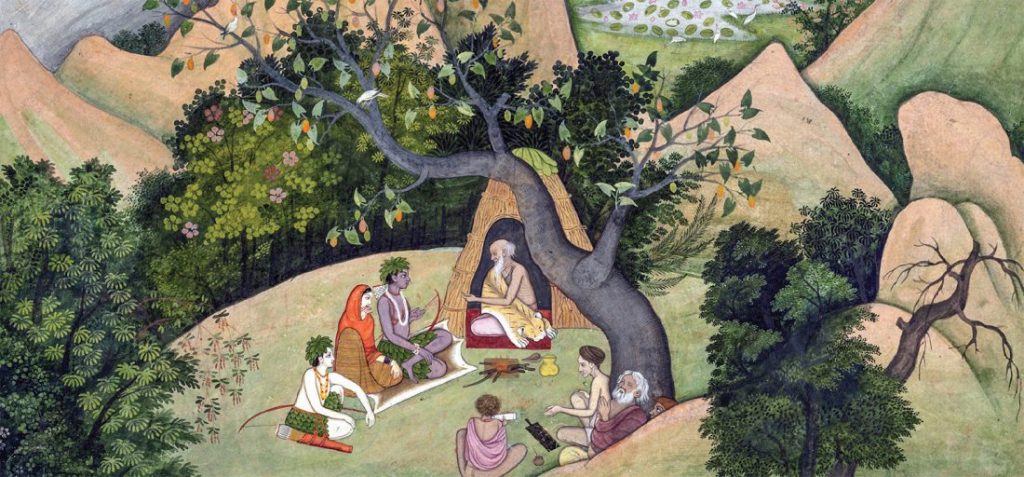

Under the patronage of the Rajputana princely states, ateliers in each kingdom developed their own distinctive style. Diverse schools of painting evolved, including Kangra, Bundi, Jaipur, Mewar and Marwar. The themes predominantly used in that era were mostly mythological stories, ragas (musical notes), religious texts, poetic literature, folklore and royal lifestyle, accompanied by explanatory text.

Numerous celebrated themes, transcending time, have been a special favorite for artists throughout the history of Indian art. For instance, the Bhagvat Purana series uses mythology as its subject. Based on a key Vaishnava scripture of the same name, these miniatures present Vaishnavism’s view of the cosmic order. The creative paintings showcase moral stories (mostly of Lord Vishnu) for a deeper understanding of dharma, bhakti and moksha.

The paintings in the Ragamala (“Garland of Ragas”) series are visual depictions of various Indian musical notes. They illustrate the different moods of the ragas, also suggesting the season and time of the day when each raga is meant to be sung. Each set of paintings is dedicated to a different Hindu God, and these are sung during the six seasons of the year.

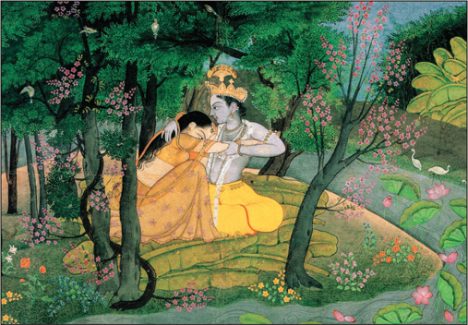

The popular Gita Govinda series, based on the devotional song of the same name composed by the Sanskrit poet Jayadeva, illustrates Radha’s love for Krishna, a humble cattle-grazing cowherd. It visually portrays the concept that a divine love for God is the only means of salvation.

Other series include the legendary Surasagara, based on the poems of saint Surdas; the Ramayana series, depicting the adventures and battles of Rama; the Dasavatara series, based on the ten avatars of Vishnu; and the Sat Sai series, a pictorial rendition of the verses composed by the poet Bihari Lal.

Brush, the Primary Tool

An artist’s brush set is widely varied in thickness and purpose. Separate brushes are used for each color, to maintain purity and vividness. Traditionally, the fine brush that achieves the intricate details, outline and coloring of miniature paintings is made of just a few strands of hair (or only one!) from the tail of a squirrel, affixed to a bird’s quill. The end of the brush is not meant to be straight and pointed; the finest brush will have a slight curve at the end, converging to a single point that makes it more versatile for achieving the precise movements and uniform curves visualized by the artist.

The Painting Surface

The most common surface used for miniatures is paper; however, silk, marble and even ivory also serve. The process remains the same for all base materials, except that silk is starched to add stiffness and smoothness.

Handmade papers used for miniature paintings are traditionally made from rice stalk or bamboo. Multiple layers of sheets are combined and then coated with a layer of asbestos or white chalk powder. This coating guarantees a thick enamel-like surface, ready to be used for painting.

Handmade Natural Pigments

After the painting surface has been prepared, specialists start making the color pigments. Only natural elements are used: minerals, vegetables, precious stones, organic inks and dyes, conch shells, pure gold, silver, zinc, lead and more.

Preparing a pigment from a hard mineral is a three-step process. The stone is first ground by hand with mortar and pestle to produce a fine powder. This is filtered in a series of washes to remove any additives and impurities that would decrease the pigment’s luster. The pigment must then be bound—the most crucial step. Binding adds fluidity, makes the pigment water soluble and stabilizes it. The binding medium is gum Arabic, the crystallized sap of the babul tree (Vachellia nilotica). The pigments are mixed with water and this gum for months to achieve a smooth, evenly spreadable paste. Even a small lump in the pigment would leave a patch that would ruin the painting.

The most extensively used colors are black, obtained from soot; white, derived from lead or chalk; blue, from lapis lazuli; red from lac, an insect secretion; and green from plants and leaves. The dazzlingly luminous yellow used by Indian artists is ingeniously derived from the urine of a cow who is fed a diet of only mango leaves and water. This diet colors the urine bright yellow. The urine is then dried into a foul-smelling hard cake to which water is added as needed.

Complex Methodology

The process that produces one of these elegant miniatures involves many steps, each performed by its own specialist.

The initial sketch is a rough outline made by the master (see page 53). The canvas’ border, which may be as much as three to four inches wide, is also marked at this stage.

In the second step, a thin white wash is applied. The artist traces the first sketch, but this time the outline is incredibly precise and fine. Now the artwork is burnished—placed face down on a smooth, hard surface and polished briskly but gently from the back with an egg-shaped crystal or agate to produce a smooth, hard, glossy surface. Layers of liquid colors are then applied one at a time, for smooth shading, and a final outline is added. At this stage there is no room for error.

A second round of burnishing now embeds the pigments deep into the paper and gives an overall union to the color pigments.

In the last stage, any embossing, ornamentation and other enhancements are added. Pin-pricks are created with a blunt needle for inlaying gems. White drops made of conch shells are added as pearls. Real gold is painted over selected ornaments.

For transparencies, often used for women’s clothes, color washes are used. This involves applying a thin layer of stronger color over the base color. After each stage of the painting is completed by the specialists, all toiling together in a shared workshop, it returns to the master artist for the finishing touches. The completed painting goes to other artisans for trimming and mounting.

Contemporary miniaturists still follow the ancient methods, preserving the authenticity of the style. However, artists today have more creative freedom; they are no longer bound to the commissions of imperial patrons in terms of size and subject.

Today’s artists have recognized organizations like Paramparik Karigar (paramparik

karigar.com) and Maukaa Art Foundation (maukaa.org) helping them gain international exposure. With renowned miniaturists like Ramesh Sharma (rameshpaintings.com), Ramu Ramdev (ramuramdev.com) and Vijay Sharma (Padma Shri awardee) creating waves internationally, the art form is gradually gaining recognition. It is no longer considered mere imitation of past artworks. This rich art form is being passed on to future aspiring artists through regular workshops in museums and certified courses in notable institutes like Himanshu Art Institute (himanshuartinstitute.co.in) and Pencil and Chai (pencilandchai.com).

Historical Trivia and Facts

The main purpose of the border is to protect the painting from the wear and tear of handling. In the old days, paintings were not displayed on walls; rather they were passed from hand to hand so that each viewer could inspect the work. Fingers would touch only the wide border and not the actual painting.

Brushes made of a single squirrel hair are the artist’s most prized possessions. In the hands of a master craftsman, this tool can produce precise outlines and extremely intricate detail.

The iconic painting “Bani Thani,” branded as “India’s Mona Lisa” by art historians worldwide, epitomizes the unique features of the indigenous style, with the high forehead, arched eyebrows, elongated eyes and pointed chin. Bani Thani was a known singer and poetess from Kishangarh (see page 65).

Traditionally, an apprentice’s training spans eight years. The first technique taught by the master is posture. There are strict rules regarding the distance of the paper from the eyes, the angle of the arm and the manner in which the brush was held. Since the painters sit on the floor and use a slanted desk, mastering good posture is essential.

Some of these workshops still exist. To see miniatures being made for sale, visit www.exoticindia.com. Relatively few modern-day artists are being trained in these exacting disciplines. This sad state of affairs may change, however.

The demand by art collectors for classical Indian miniature painting has peaked significantly over the last few decades. Top auction houses like Christies, Sothebys and Bonhams have presented rare collections of Indian miniatures, ranging from the 16th to 19th centuries. Just last year, Christie’s London witnessed a painting from the famed “Ragamala Series”go under the hammer for an impressive sale price of $266,000, more than doubling pre-sale expectations.

Uday Shankar in the 1930s

Dinodia: Stefano Paterna

metropolitan museum of art

Exploring India’s miniature painting tradition is like stepping into a world of beauty and intricacy. These paintings, despite their small size, are filled with immense detail and artistry, showcasing stories, landscapes and cultural nuances with incredible precision. The use of vibrant colors and the meticulous techniques employed by the artists are truly awe-inspiring. Each miniature painting is a masterpiece in its own right, reflecting the rich artistic heritage of India. This blog post does a wonderful job of introducing readers to this fascinating tradition, offering a glimpse into a world where artistry knows no bounds. Looking forward to delving deeper into the world of Indian miniature paintings!