Here we explore a range of sacred plants and the unique ways Hindu beliefs in nature’s divinity have helped protect and conserve our natural world

By Savita Tiwari, Mauritius

Throughout human history, plant and tree worship has been found in many religions, sects and cultures. Hindus practice this worship on a daily basis. Plants and trees are part of our stories and prayers. Sometimes they represent the Gods themselves.

Divinity resides in all prakriti (primal substance; original matter), including botanical life, which is greatly revered. These creations of nature are sometimes even seen as Divinities whom humans can touch, nurture and worship. After all, we depend on them for our very survival—for oxygen, food, clothing and shelter. What do they need from us? Nothing. They grow on their own, with water and sunlight, and care for themselves. They simply give—a quality of God.

Each person must get closer to prakriti to start their own journey towards purusha (Universal Spirit) within, by exploring their own path toward personal harmony with the plant world. As the blessing sloka from the Rig Veda says, “May soma together with the plants be auspicious to all.”

We as Hindus interact with the world of nature both spiritually and physically, and regard plants and trees as an extension of the Divine. In religious ceremonies, leaves, flowers and fruits are used as offerings. All our prayers begin with the dhyan mantra, where devotees offer a handful of flowers as a token of their love, and end with the pushpanjali mantra, when we offer flowers to the feet of the Lord with gratitude.

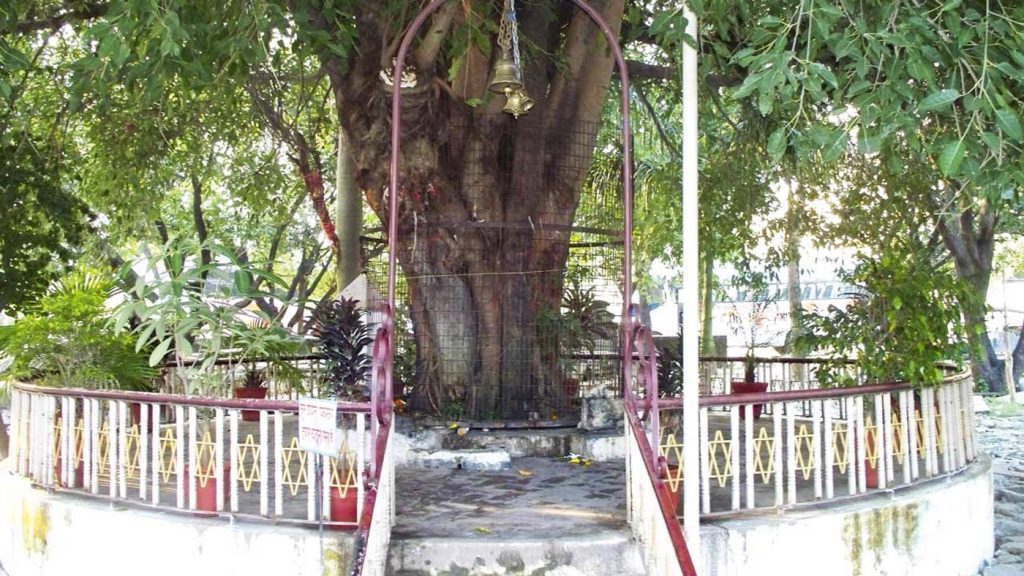

Sometimes the plant itself is the Deity, such as during Tulsi puja, Manasa Devi puja, Vatsavitri puja or Amla Ekadashi. The Aswatha tree is especially watered and worshiped each Saturday, as it is believed the Tridev—Brahma, Vishnu and Siva—along with Lakshmi reside in the tree that day.

Plants and trees are also worshiped in the form of Shakambhari Mata, the Goddess of vegetation. The rudraksha tree is considered as Siva Himself. Rudraksha malas are worn by Saivites, just as tulsi-bead malas are worn by Vaishnavas. Then there are divine flowers, like the lotus that grows in water and the pearl flower said to grow on kalpavriksha in heaven.

Although all evergreen flowers can be used in prayer, some flowers are not to be offered for certain Deities. For example, the ketki (pandanus) flower is usually not offered to Siva, as put forth by the Siva Purana. Traditionally, aksada flowers are never used during Vishnu puja, and bilva leaves are not offered to Surya, the Sun.

In Hindu families, the samskara (mental impression) of respecting plants and trees is ingrained early in the hearts of children by elders. Children are educated about the importance of plants through various rituals, mantras and slokas from Vedic literature, and also through mythological stories.

The Vedas and other Hindu texts contain countless references to the sacred use of plants. Some of the earliest are the Rig Veda’s many references to soma, a plant-based tonic that was a fundamental offering in the Vedic ritual. In the popular story of Samudra Manthan, the churning of the ocean, fourteen treasures are said to have sprung from the ocean. One of these was kalpavriksha, the wish-granting tree. According to the Padma Purana, Devi Parvati asked the divine tree for a girl child and was blessed with a beautiful daughter, Ashok Sundari.

In another Puranic story, Sage Markandeya was shown a petrifying vision of universal dissolution, during which he also saw Vishnu as a baby lying on a banyan leaf. The vision indicated that after every destruction there is new life, starting with a human baby on a leaf—in other words, purusha existing on the support of prakriti.

A Sanskrit sloka from the Matsya Purana highlights the importance of reverence for trees: “Ten wells are equal to one pond, ten ponds are equal to one reservoir, ten reservoirs are equal to one son, and ten sons are equal to one single tree.”

Examples of Plant Reverence

The khejri tree, also called jaanti or shami, is sacred in the state of Rajasthan. Both frost and drought resistant, it plays a key role in preserving the ecosystem in this desert state. Khejri also acts as a host plant for banyan and ashwatha trees, which need moist conditions to germinate.

A famous event from 1730 illustrates the importance of this tree. The Bishnoi are a Vaishnava people from India’s Western Thar Desert. Of their guru’s 29 principles, the 19th states: “Do not cut green trees; save the environment.” The Maharaja of Marwar was building a new palace and dispatched his minister for the needed lumber. A mother and her three daughters, members of the Bishnoi, tried to protect a grove of khejri trees and were killed to end their protest. After this occurred, 83 Bishnoi villages joined the cause. Over the next several days, 363 adults and children gave their lives, each hugging a tree while the king’s men attacked them with axes. Awed by this peaceful resistance, and horrified by the violence he had caused, the king recalled his men. He personally traveled to the site and solemnly apologized for his minister’s actions. The grove became a place of pilgrimage for the Bishnoi people. This sacrifice became the motivation for the Chipko (“tree-hugging”) Movement in the state of Uttarakhand in the 1970s, which was a campaign against commercial logging operations.

The Bheel tribe in Madhya Pradesh’s Jabua district pray to the kalam tree (Mitragyna parvifolia) to grant their wishes. They believe the tree is the abode of their God Kalamdev. Devotees perform an elaborate ritual offering to the tree in gratitude for fulfilled prayers. This rite can cost nearly as much as a wedding, with the entire community present for the ceremonies, feast and other cultural events. Other names for this tree include kaim, kadam and Hari Priya.

The pancha vriksha, “five sacred trees” believed to be present in Lord Indra’s garden in higher lokas, are mandara (prickly coral), parijat (night-flowering jasmine), samtanaka (unidentified), harichandana (sandalwood) and kalpavriksha (banyan). It is said that mandara’s shade relieves physical ailments and mental stress and that the fragrant and mysterious parijat brings positive states of mind. The samtanaka tree’s leaves promote fertility, and harichandana is known for its fragrance and cooling effect. Kalpavriksha, the tree of eternity that emerged from the churning ocean, was offered to Indra, who took it to heaven. It is frequently mentioned in Sanskrit literature as a wish-fulfilling tree.

The pancha pallava are “five leaves,” from sacred trees used in several forms of worship. The particular array varies according to location and availability, but normally includes mango, sacred fig, cluster fig, white fig and banyan leaves. Interestingly, at Premnagar Ashram in Haridwar, leaves are used from a single tree of the same name, pancha pallava. This remarkable tree is a combination, all five trees growing together as one.

Panchavati is a cluster of five trees that represent the five physical elements: earth, water, fire, air and space. The trees most often included in this combination are banyan, sacred fig, bilva (wood apple), amala, ashoka, cluster fig, curtain fig, neem, shami (ghaf) and mango.

Sacred Groves of India

Although no extensive research on sacred groves has been conducted, experts believe there are between 100,000 and 150,000 sacred groves in India. These communally protected areas of nature are fragments of forests of varying sizes that usually have important religious significance for the community that protects them. Sacred groves are frequently associated with nature spirits, forest tribes, guardian Deities such as Ayyanar and Amman, animal ancestors such as tigers, serpents or gaur, or Gods and Goddesses such as Ayyappa and Durga.

The tradition of maintaining one-fourth of the land of every village for groves, in the name of folk Deities or ancestors, is centuries old. In Maharashtra, sacred groves are called devrae, and in Karnataka devaru kadu. In Tamil Nadu they are called kovil kadu. In Rajasthan they are called oran or beehad. Many are believed to be at least two millennia old.

In Kerala and Karnataka alone, over 1,000 Deities are associated with sacred groves. More than 365 forest Deities are worshiped in sacred groves across the Himalayan state of Manipur. The festival of Lai Haraoba is celebrated in special regard to these areas. There are also many man-made sacred groves surrounding temples and burial sites.

Types of Sacred Forests

Three types of sacred forest are categorized in Vedic scriptures: tapovan, mahavan and shrivan. Tapovan is a forest populated by saints and rishis for tapas (austerities and deep meditation). Mahavan is a term used to describe huge natural forests. Because ordinary people are not permitted to access these two forests, they are considered sanctuaries for flora and fauna. Shrivan refers to lush forests and groves; the name means “forests of Shri” referring to Lakshmi, Goddess of wealth. Legend says there was also a personal forest of Siva and Parvati known as anandavan.

Plants as Medicine

The oldest Sanskrit text on ayurveda, Charaka Samhita, says we need to sustain our health to achieve the four goals of human life: dharma (duty), artha (wealth), kama (enjoyment), and moksha (eventual release from the cycle of reincarnation).

The vast majority of ayurvedic preparations are plant-based. Ayurveda mentions three plants as amrita (divine nectar) plants: guduchi, garlic and haritaki. Ashwagandha, a winter shrub, is considered the king of ayurveda, and turmeric is the golden herb.

Besides ayurveda, other centuries-old natural plant–based medicinal systems include siddha, which originated in South India, and sowa-rigpa from the Himalayas. Siddha is said to have been taught to Parvati by Siva. Parvati passed it on to Nandi, who taught the 18 siddhars, the original practitioners of Siddha. One of these was Sage Agasthya, who popularized the Siddha tradition and founded the system of siddha medicine. In siddha, 108 plants known as karpa mooligaigal (disease herbs) are commonly utilized to treat human ailments.

The name sowa-rigpa, from the Bhoti language, means “knowledge of healing.” It is one of the most important healing systems practiced in India, mostly in the Himalayan areas and Tibet. It is thought to have originated in India from the Buddha.

Not only can plants and trees heal us, but they also bring the light of nature into our bodies. Plants and trees in Hinduism represent the Divine on earth. In contrast to its widespread decline within other religions, plant and tree worship in Hinduism remains vibrant on a daily basis, such as daily watering the holy tulsi plant in many Hindu households.

Conclusion

Plants and trees start their journey as seeds from the darkness under the earth and then flourish in the brightness of the sun. They can reach the mystic heights of the sky and connect humans with all three lokas (realms of existence). Understanding the almost supernatural powers of plants and trees is key to the eternal completeness most spiritual humans seek, so do not hesitate to nurture this unique spiritual connection.

About the Author

Savita Tiwari grew up in India and is now a resident of Mauritius. She is an avid journalist, blogger, writer and poet with a love of dharma and a penchant for learning more about Hinduism. Contact: savitapost@gmail.com.