The sprawling, redesigned campus is now open for students and faculty

By Anuradha Goyal, India

If Xuan Zang, the 7th-century-ce Chinese traveler and Buddhist scholar, were to visit his beloved alma mater at Nalanda in the current-day state of Bihar, he’d find only a portion of its ruins accessible and excavated. Viewing the exposed brick structures, he would have memories of how they were once pristinely lime plastered. He would become nostalgic as he strolled through the vihara, Buddhist monastery, where he lived, studied and taught. He might be pained to see the stupas of his revered teachers in dilapidated shape, but as a wise man he would understand the vicissitudes of time. He would see people he thought he knew, but they were not the students and teachers he remembered. Rather, they were visitors from around the world—such as there had been in his time as well.

Founded in 427 ce as a Buddhist monastic university, Nalanda was purportedly the world’s first residential college, at one time drawing as many as 10,000 students from across Asia.

The university, reopened in 2014, was founded during the Gupta Empire. The Hindu Gupta monarchs recognized the strength and value of Buddhist intellectual inquiry. Nalanda literally means “the giver of knowledge,” and the university is credited with having nurtured the greatest Buddhist scholars. After studying there, Xuan Zang carried 657 Sanskrit texts back to China, translated them and contributed to the development of Buddhism in China. The university flourished, surviving two attacks, right up to the Pala dynasty in the 12th century, until its final demise by Turko-Afghan invaders.

Xuan Zang would be sorrowful to know how his university, with its library of nine million books, had been ransacked and burned for three months. But he would gain solace from the sight of the sprawling new Nalanda University campus in the city of Rajgir, just south of the Nalanda ruins. He would see how the development of this new university takes inspiration from his own campus. Xuan Zang, avid traveler and philosopher that he was, would easily ride the currents of time and accept that what lies before him could be a new manifestation of his university, this one belonging to the 21st century and developing the minds of new students so they might contribute to the present times.

Campus Infrastructure and Design

I arrived on campus in the late evening, passing through a gate designed to resemble a chaitya—a high roof with a distinctive rounded profile. As we completed the entry formalities, the nearby stupa began to undergo a mesmerizing transformation of colors. I was struck by the beauty of the lighting around me. Lit buildings were reflected in ponds. I passed the Indian flag fluttering proudly on top of a 108-foot pole as I was led to a fashionable guesthouse. The staff took great care to identify for me the various buildings we passed.

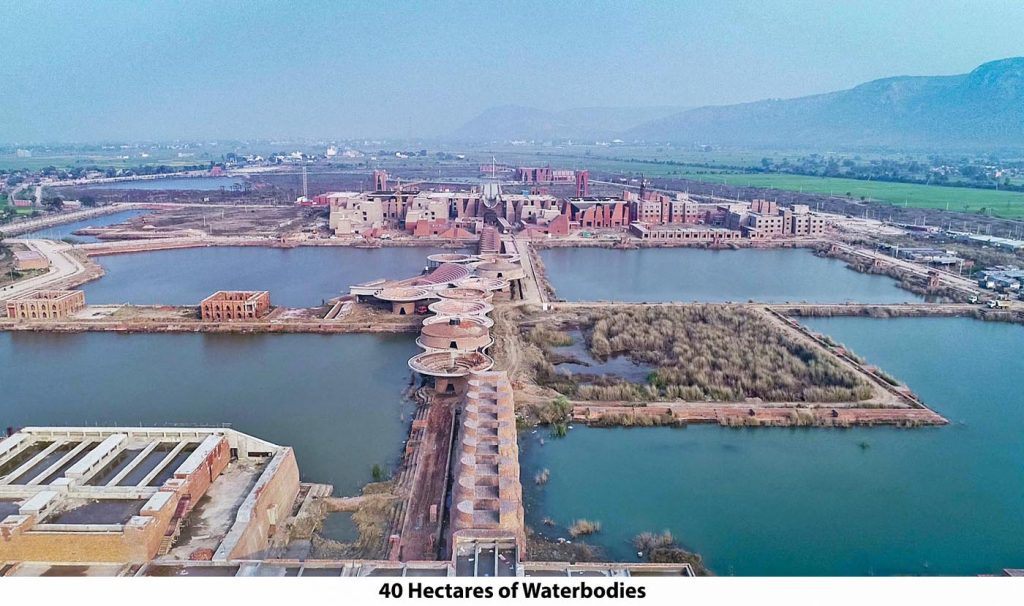

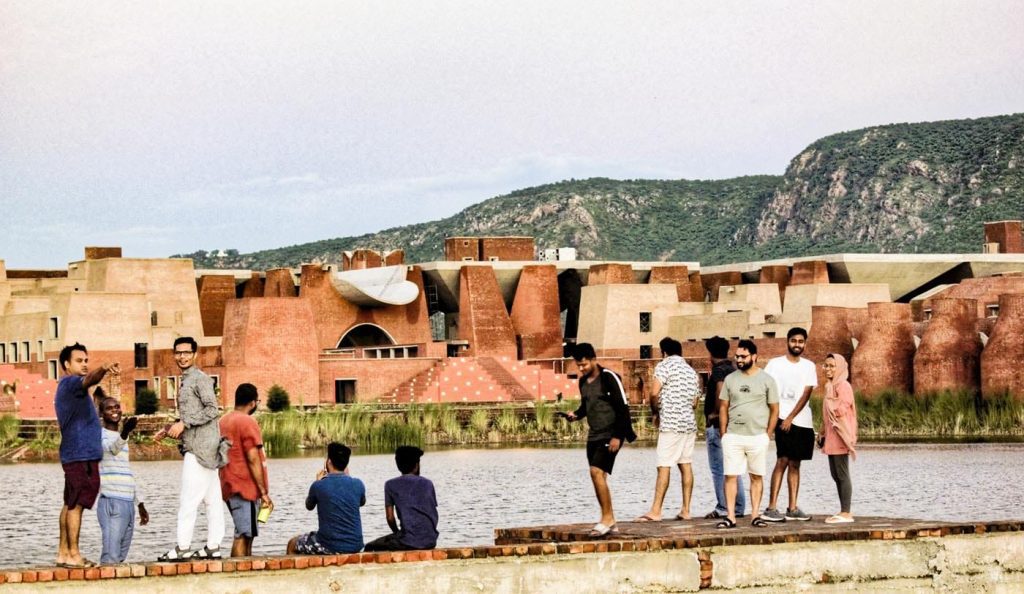

The following morning, I was treated to a guided tour by Dr. Mir Islam and Manoj Ji, both integral members of the engineering team responsible for constructing the campus. With its numerous ponds, the area proved to be an idyllic setting for an early morning stroll. The campus architecture, characterized by the unusual shapes and exposed red brick buildings, exuded an atmosphere of nostalgia, mystique, and intrigue.

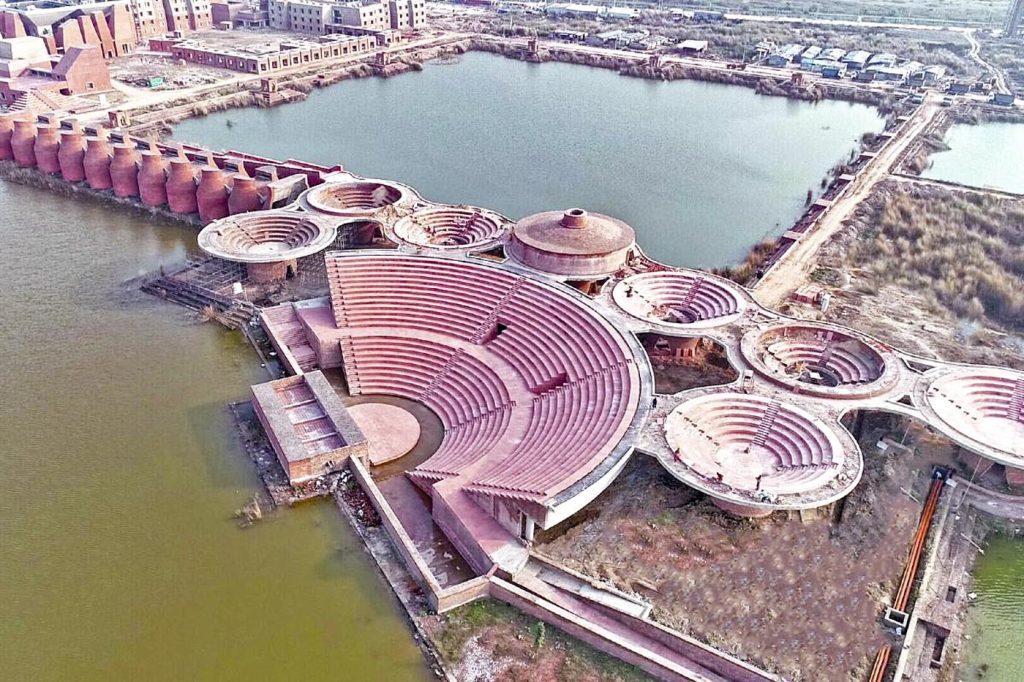

Manoj pointed to what looked like inverted grey stupas across a pond. As I was naturally expecting stupas on a campus inspired by a Buddhist vihara, I asked, “For what reason are the stupas inverted?” He explained that they were not stupas at all, but rather amphitheater classrooms with increasing seating capacity to sit as you go up. He asked me to focus on the negative space between the stupas and then I caught on. A meditating Buddha sat in the middle. It occurred to me that such imaginative play with space is what we often miss in modern Indian architecture.

We reached two red brick pavilions erected beside another body of water. These structures resembled medieval Baradari, the 12-door open courtyards that we see in many royal buildings around India. But the comparison ended there when I learned how these structures stand on water storage tanks, a part of the University’s unique water management system. The campus uses the age-old local traditional system of water management called ahar-pyne. Water runs through a series of channels called pyne, which connect to retention ponds called ahar. In the past, this system helped the region to withstand unpredictable floods and droughts. I was reminded of a similar system I had seen at the Kanheri Caves in Mumbai, where stone-carved water tanks became filled to the brim with rain water, which then ran to a tank at a lower level. Sringaverpur in Uttar Pradesh has a similar ancient tank system that stores excess water from the Ganga during the rainy season. Here on the Nalanda campus, the water management system provides water not only for everyday use, but for ongoing building purposes as well.

If you were to build a new university campus, what would be the key elements or features of its infrastructure and design? I would have loved to observe the first meetings of those who planned the new Nalanda. I like to imagine them writing with old-fashioned chalk on a big blackboard: “Water.” Water would be foreseen to be crucial for the future, and students who will shape the world must understand its value.

The campus is spread over 455 acres, gifted by the government of Bihar in 2011. Forty hectares—roughly 100 acres—of the campus area is water. In fact, campus construction began with excavating ponds so that water for construction activity could be retained. With 100% rainwater collection, the campus can meet the water requirements of 5,000 people with ample buffer for 18 months. Treated waste water is recycled for flushing or landscaping through a dedicated supply network. No groundwater is used on the campus—a significant achievement for long-term sustainability goals. Furthermore, native and aquatic plants will be introduced to ensure natural air purification and to make the campus climate resilient. In a few years one should be able to see orchards of local fruit trees such as mangos.

The campus’s designers might have also brainstormed around “earth.” During excavation, the top, fertile layer of soil was preserved for horticulture purposes. The mud was used to build roads as well as compressed blocks for buildings.

The tall brick structures, tapering towards the top, resemble the gopurams of South Indian temples. Manoj ji confirmed that they are indeed inspired from gopurams and there are as many as 108 of them spread across the campus. In addition there are four stupas and 22 chhatris, or cenotaph-like structures. Even utility buildings like water tanks were provided a character by being covered by red bricks. “So many bricks!,” I exclaimed, thinking of the horrors of brick kiln pollution. But I was told these are not common burnt clay bricks, but rather Compressed Stabilized Earth Blocks (CSEB) that are created in-situ using local soil. The soil is dampened, mixed with a chemical binder such as Portland cement, mechanically pressed at high pressure, then dried. These are economical, non-toxic, resistant to fire, insects, mold and sound and are known for better thermal control for external temperature changes.

Solar and other alternative energies were also integrated into the campus design. At the edge of the campus is a 20-acre solar park which can generate up to 6.5 MW of electricity. Diagonal solar panels are spread out to make the most of the abundant sunshine. This park can produce ample energy to sustain the whole campus. Waste generated in the campus, including horticulture waste, is converted into energy using a bio-methanization digester. Solar energy is used during daytime, and biomass-generated electricity is used at night. When the campus is fully occupied by its planned 5,000 people, the waste generated will give ample biomass energy, the second renewable source of energy.

Kamal Sagar or “academic spine” was to me the most beautiful part of the campus. Here you see a row of stupas next to a pond, with a serene open-air amphitheater in red stone. The linear placement of the stupas brings to my mind a caravanserai. But the most intriguing structures are those that intersperse the stupas and amphitheater and look like tall UFOs or umbrellas. These are open mini-amphitheaters for the students to interact. Each has a slightly different design—some are approached through a staircase from the ground, while others are entered from the top. Each has concentric steps on which students or teachers can sit while engaged in group discussions. I find the design brilliant—you have private space, yet you are out in the open, in the elements of nature.

A circular structure with a stupa-like roof is a chanting room. Its acoustics allow chants to reverberate; I could only imagine how the collective chanting resounds within the room and sends special energy far beyond.

Even the more traditional blocks of classrooms show innovation. At the Nalanda ruins, you can see the different layers of construction stretching back more than 700 years. Pyramidic staircases climb today’s academic buildings, reflecting ancient foundations built upon even more ancient foundations. Most innovative are the interiors, with state-of-the-art interactive classrooms that employ the latest in digital technology.

After covering a lot of ground, my tour ends with buildings still under construction. One of these is a 2,000-seat auditorium; the other, in a circular shape, will become a multi-floor library. I wonder if one day the library will be as impressive as its predecessor? All its books will be RFID (Radio Frequency Identification) enabled, making it truly belong to the 21st century.

While large campuses often have one or two buildings that can be classified as “green,” Nalanda University has 200 sustainably green structures. Utilizing emerging technologies, the campus design embraces the very philosophy that the university wishes to send out into the world—teaching harmony with nature and fellow human beings. Following my tour, I wish to learn about the ideas the campus will generate through the classes in its unique eco-friendly spaces. What are the subjects to be taught, and who decided upon them?

Purpose and Mission

In 2006, Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, the visionary former president of India, proposed re-establishing the ancient Nalanda University. Around the same time, serendipitously, Singapore sent a proposal to the Indian government to revive Nalanda. The next year, the then sixteen member countries of the East Asia Summit endorsed the proposal to rebuild Nalanda University and thereby re-establish their traditional ties across Asia. The diverse member countries at that time were Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand and Vietnam. What a rare situation it is that sixteen countries would come together, readily sharing a common vision and committed to realizing it! A mentors group was established with the famous economist and Nobel laureate Amartya Sen as its head, and in 2009 more member states joined the Summit. While India remained the lead player in establishing the university, member states contributed endowment funds for various programs. Australia, for example, gave support for the School of Ecology and Environmental Studies for a period of three years.

Imagine you were participating in a mentors group, establishing the departments and courses for a new international university. I would have liked to listen in on the discussions about where to give emphasis. The old Nalanda was famous for Buddhist philosophy, mathematics, astronomy and anatomy. It also had courses in the fine arts and the art of war. Today, which courses could bring unique knowledge from Asia to the whole world—a world which struggles with so many issues related to peace, health, ecology, poverty, equal opportunity and more?

One of the university’s mandates is “to contribute to the promotion of regional peace and vision by bringing together future leaders of East Asia, who by relating it to their past history, can enhance understanding of each other’s perspectives and share that globally.” Professor Sunaina Singh, former Vice Chancellor of the university, explained to me that a core value of Nalanda University is character building so that students can contribute to a peaceful and tolerant society in the future. While the education is academic, it also emphasizes the understanding of religions that belong to the Indian subcontinent. There are master’s and PhD programs in Buddhist studies, philosophy, and comparative religions, and masters in Hindu studies.

What is attractive to students, most of whom are working toward an MA or PhD, is the inter-disciplinary approach allowing them to pick and choose courses from a menu of subjects, rather than follow a prescribed course of study. This approach is rooted in the ancient knowledge systems in which Shruti, Smriti, Vedanta, Purana and Itihasa texts weave together various types of knowledge. Such fluidity between different streams of study encourages thinking out of the box and leads students to be more innovative, creative and humanistic in whatever they ultimately choose to do. An engineer can choose to do his masters in history or a doctor can choose to do a masters in Hindu Studies or world literature. You can drop the baggage of your past studies, although the minimum qualification clauses as mentioned on the website for various courses do apply. While the system is beneficial for students who may want to change streams, all students will find their paths invigorated by a cross-pollination of ideas.

Memorandums of understanding with major universities in member countries as well as other leading institutes around the world encourage further diversity in thought. Nalanda University recently joined the launch of AINU, ASEAN-India Network of Universities, establishing vital linkages between premier institutions in the region. Faculty exchange, student exchange and joint research are key activities of this consortium. I see AINU as a key initiative of India’s “Look East” and now “Act East” policy that seeks greater collaboration between Asian countries with common cultural ties.

Faculty and Students

While the university has set its priorities in terms of subjects, it faces a big challenge attracting highly qualified faculty from metropolitan cities to come teach in the remote town of Rajgir. Bihar still carries the perception of being backward, with few modern facilities, and there are safety concerns. With medical facilities limited—a small health center operates on campus—not many want to move here with their families or leave them behind. But learning from the days of the lockdowns, the university has introduced online classes in order to access top faculty from around the world. It is also introducing small courses for which they can invite visiting faculty to be on campus for shorter durations. In April 2023, noted economist Arvind Panagariya was appointed chancellor, and no doubt he will be building a strong faculty in the years to come.

Student enrollment is another concern, but it is rising steadily since the University opened in 2014. Professor Singh pointed that while most universities and institutes need time and resources to build a strong brand, Nalanda University has a legacy branding of being a Vishwa Guru, the knowledge leader of the world. Currently there are 800-1,000 students, 80 percent of whom are international. The first batch of students arrived at the makeshift campus in 2014. By 2019, the new campus was operational with its first five buildings. Today, students from over 30 countries are studying. Around 250 of them, enrolled in mMasters and PhD programs, live on campus, while the rest study remotely in short-term courses.

At an on-campus, semi-open-air café I approached students engaged in informal discussions. They told me they appreciate the calm environment that allows one to think and contemplate. I concur. I am a restless person by nature, especially when traveling, wanting to move around and experience and see as much as possible. But at the Nalanda campus, I wanted to sit and think about the meaning of my work and how it impacts the world around me. In a natural setting, distanced from the business of city life, you can concentrate. I spoke to a student from Türkiye studying Buddhism with an aim to understand philosophies of world religions, with a goal to build a career in a not-so-popular subject in her country. She was clearly benefitting from the freedom to pursue her interests in a supportive environment.

Students told me they appreciate that the faculty are so accessible, in contrast to faculty in other institutions. Some professors taught during late evenings instead of the usual teaching hours. Of course, some students were lonely or bored, but I imagine over time they will appreciate the open space and calm for thought and learning that Nalanda provides. Students have many options for recreation. Some were playing badminton, and a huge sports complex is nearing completion. I wondered if there might be a study that bridges the ancient physical disciplines like Kalaripatayu martial art and hatha yoga with modern games like football and tennis.

Most students live on campus in a beautifully designed hostel. Two dormitories remind you of those that you see at Nalanda ruins, but they have modern-day facilities. Since the campus is equipped with radio frequency antennas, the students have continuous wifi. In a state-of-the-art dining room, underneath a huge hanging globe, students enjoy cuisines from around the world. Above, conical-shaped roofs collect rainwater that runs through channels concealed within pillars out to the ground and surrounding water bodies. This water system helps keep the buildings cool, reducing the need for air conditioning by at least 30 percent, through what is called the Desiccant Enhanced Evaporative (DEVAP) technology. Furthermore, thick cavity walls within a double-skin envelope help to retain heat during winters and maintain coolness during summers—a kind of natural thermal insulation.

Offerings for Aspiring Students

Nalanda is exclusively a graduate school, currently offering master’s courses and doctor of philosophy programs. The academic framework contains Foundational, Bridge, Advanced and Specialized courses that focus on emerging research domains and India-ASEAN interconnections. It includes courses on languages, Nalanda heritage, geo-informatics, biodiversity and conservation, Buddhist studies, comparative religion, ecology and environmental studies, historical studies, masters in management streams, world literature and Hindu Studies. There are dedicated centers for Bay of Bengal Studies, Common Archival Resource and Conflict Resolution and Peace studies, making a total of six schools and 12 academic programs.

The School of Buddhist Studies, Philosophy and Comparative religions offers a master’s degree and PhD programs in Buddhist Studies, Philosophy, and Comparative Religions, along with masters in Sanatana Hindu Studies. This puts the university among just a handful in India that offer Hindu courses.

There is special emphasis on the study of Buddhist ideas and values in relation to other philosophical and religious traditions. The wider social-historical-cultural contexts of the development of Buddhist traditions are examined through an innovative and interdisciplinary curriculum.

The School of Ecology and Environment Studies, the first school at Nalanda University, has offered a master’s course since August 2014. It aims to promote education and research on the interactions between the natural environment and human activities. The School of Historical Studies offers a master’s degree along with elective courses.

The School of Languages and Literature/Humanities offers a master’s degree in World Literature along with diploma and certificate courses in languages like English, Korean, Sanskrit, Pali and Tibetan. A MBA in sustainable development is offered by the School of Management, with an aim to be a global leader in responsible management.

The minimum criteria for seeking enrollment is 55% or 2.2/4.0 GPA or equivalent in a undergraduate degree. Students coming from any stream can apply for any program, but may not apply for more than two programs. Learn more about this and other aspects at nalandauniv.edu.in.

My Takeaways

The new Nalanda University has a strong legacy to follow, but most important is how it becomes relevant to current and future generations. While the inspiration for a knowledge flow rooted in Asian culture and thought comes from the ancient university, the new university caters to the future needs of societies within and beyond Asia. This unusual campus, conceived with great care, shows the way forward in terms of conservation of water, earth and energy. The academic design has every potential to nurture generations of students who are both strong in their fields and dedicated to the wellbeing of the world. If only Xuan Zang, renowned for his writings about his extensive travels in the 7th century, could write about his time travel to the present Nalanda. I would wish to read his commentary. I believe he’d note the challenges that the university faces but commend the vision and serious effort shared by the East Asia member states. He might wish to sit in on classes to ruminate about subjects new to him, or to offer advice on teaching the subjects about which he knows best. Of the campus and its technology, he’d be in awe.

I had visited the ruins of ancient Nalanda many years ago, before it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. When I re-visited it after my tour of Nalanda University, comparison between the two was natural. The old university has a vihara-style layout. There are rows of classrooms with a temple or a stupa and a platform for the teacher. These viharas are surrounded by rooms similar to modern dorms—a row of rooms, each with a capacity to accommodate up to two students. In the new university you don’t see the same types of temples, but the open-air mini amphitheaters recreate the aura of the ancient ruins.

At the Nalanda ruins I encountered a group of monks from Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka. Their reverence for Nalanda revealed its significance in the Buddhist world. No wonder there are so many visitors to the monuments and so many students coming from universities across Asia. The resurrection of Nalanda University will certainly bring peoples of the eastern region together to share a common ethos. The Archaeological Survey of India’s site museum showcases murtis excavated from the ancient site. You can view old photos of the excavation next to the objects on display. One of the objects capturing my interest was a pot with multiple openings used for Naga worship.

It is clear from the many historical monuments, temples and artifacts in the region how India’s three ancient religions of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism flourished here. For centuries, Nalanda had attracted the greatest scholars in the world, pushing the boundaries of human knowledge and understanding. Now the rich story of Nalanda, for a time interrupted, is poised to continue. May Nalanda remain the destination of knowledge seekers, a center of spirituality, and the origin of important thought that benefits all the world.

About the Author

Anuradha Goyal is one of India’s leading travel bloggers. Her focus at www.IndiTales.com is ancient India and temple architecture along with old techniques such as water management with step wells.