India’s smallest and northernmost state of Sikkim is known for its Hindu, Buddhist and indigenous traditions, high mountains, serene environment, organic-only farming policy and, lately, for its strategic geography at India’s border with China and Bhutan. Join us as we explore Sikkim’s religions and cultures.

BY RAJIV MALIK, NEW DELHI

NESTLED IN THE LAP OF NATURE IN THE Himalayan northeast of India sharing borders with Bhutan, Tibet and Nepal, Sikkim is known the world over for its breathtaking scenic beauty, clean environment, magnificent Mt. Kanchenjunga and, most recently, being India’s first all-organic state. With 607,688 people as of 2011, it is India’s least populated state and one of the least dense, with just 86 people per square kilometer—by comparison, Singapore is 7,988.

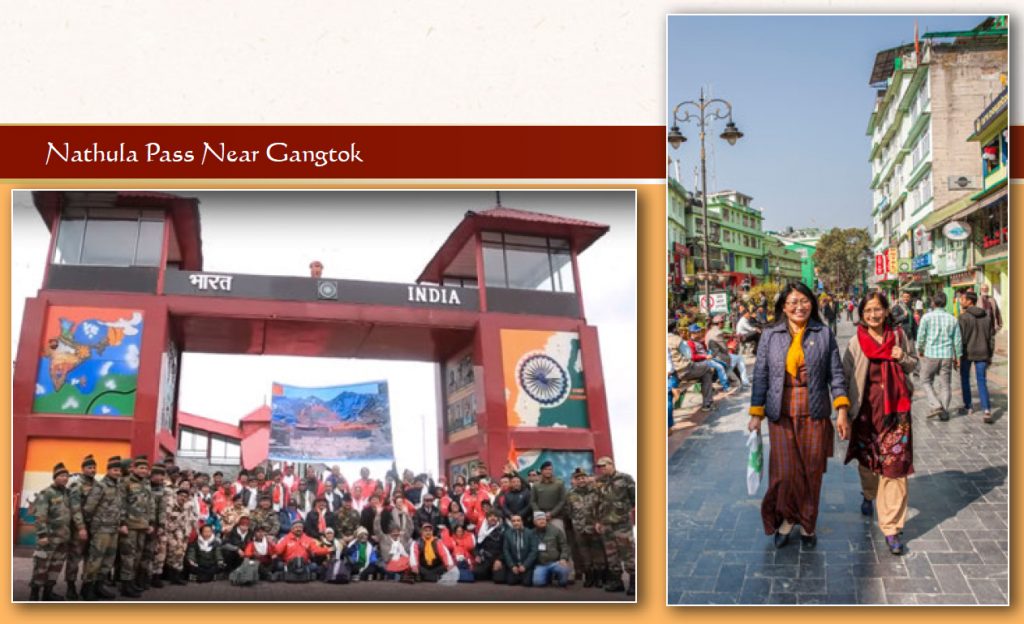

Sikkim appears in the Hindu epics as Indrakil, the “Garden of Lord Indra,” but little is said about it. The Old Silk Route, a branch of the Silk Road which has existed since at least the first century bce, ran from Lhasa in Tibet to Bengal via the Nathu La Pass on what is now the border of Sikkim and China.

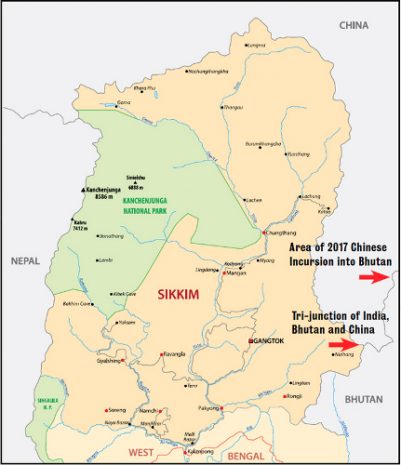

Nathu La Pass, the fastest land route for pilgrims from India to reach Mount Kailash in Tibet, lies just 37 miles from Sikkim’s capital, Gangtok. Opened only recently to pilgrims, the pass was closed again as tensions flared with China over a border dispute with neighboring Bhutan, an Indian protectorate. Sikkim, Nepal and Bhutan sit just north of the Siliguri Corridor, a thin stretch of land called the “Chicken’s Neck”—less than 17 miles wide at one point—which connects the main part of India with its northeastern states. Chinese troops stationed in Tibet’s Chumbi Valley, between Sikkim and Bhutan, are a strategic threat, one readily felt here. The Indian army is much in evidence, and the movement of foreign nationals is restricted.

Photographer Thomas Kelly and I spent a week exploring Sikkim aided by a local guide, Manorath Dahal. With the blessings of Swami Tejomayanada, we were also assisted by Brahmachari Smaran Chaitanya and other devotees of the local Chinmaya Mission.

This very hilly state has neither airport nor train service. One flies into Bagdogra in West Bengal, then drives about 78 miles north to Sikkim’s capital, Gangtok, on the picturesque National Highway 10. Heavily trafficked in normal times, the highway is sometimes blocked by landslides or shut down by a bandh (strike) called as part of periodic protests in north Bengal. At a cost of US$44 million, Pakyong airport is now under construction 20 miles south of Gangtok. Carved into a steep hillside, it uses innovative soil packing technology to create retaining walls over 200 feet high on the down-slope side of the 4,700-foot runway. That that altitude, it will be one of the five highest in India.

Historical Background

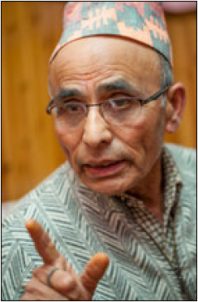

In order to understand Sikkim’s complex religious landscape, some historical background is necessary. Among others, Rudra Prasad Podiyal, former principal director of the government’s education department and a specialist in Nepali literature, helped us understand the origin of the state’s various communities.

Sikkim’s earliest inhabitants were the Lepchas, presently 15 percent of the population, about 60,000 people. They originally followed the Mun religion—called “animist” by anthropologists, but sounding like a variation on Hindu tradition, with its beliefs in the chief Goddess Nozyongnyu, various other Divinities, rites of passage, festivals and ritualistic worship. Since at least the 8th century this area has received Buddhist migrants from Tibet, known as Bhutias. Today they number about 70,000. Guru Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche, is believed to have visited here in the 7th century. With this strong Tibetan influence, the Lepchas mostly converted to Buddhism, but still retain many Mun beliefs and practices. The state has a number of architecturally marvelous monasteries and is a popular pilgrimage destination for Buddhists worldwide.

Old Silk Route: One of the last pilgrim groups to Mount Kailash allowed through the Nathu La Pass before it was closed on June 27, 2017; shoppers on Mahatma Gandhi Road

Sikkim emerges in modern historical records in 1642 with the establishment of a Tibetan Buddhist monarchy or Chogyal. Over the following centuries, the area saw invasions and retreats from Nepal and Bhutan. The British took a strong interest in the region in the early 19th century, as Sikkim provided a trade route to Tibet. When the entire state eventually came under British rule, many Nepalese were brought here to develop agriculture and mining.

Land of Sikkim: Map of Sikkim, India’s least populous and second-smallest state; strategically located, it is bordered on the west by Nepal, the north by China and the east by Bhutan

Kangchenjunga as viewed from Darjeeling—at 28,169 feet, it is the world’s third highest mountain

When India gained independence in 1947, Sikkim chose not to join India, instead retaining the Chogyal monarchy. It was granted protectorate status, with India controlling its external defense. The 1962 border war between India and China involved skirmishes at Nathu La Pass, which was then shut down for decades. Anti-monarch sentiment rose in the state and, with increasing security concerns, the Sikkimese voted overwhelmingly in 1975 to abolish the Chogyal and become India’s 22nd state.

Nepalis have continued to migrate to Sikkim, today constituting 63% of the population. The original Lepchas are 6.5% and the Tibetan-origin Bhutias 7.6%. Other ethnic groups here include Limbus, Sherpas, Tamangs and migrants from elsewhere in India. Religious affiliation falls generally along these ethnic lines, with the 58% Hindus being mostly Nepalese and the 27% Buddhists being Bhutias and Lepchas. Christians, mostly from the Lepcha community, comprise 10% of the population, a consequence of 19th-century missionary efforts. Intermarriage between communities is increasingly common.

Sikkim is home to ancient Hindu and Buddhist sacred places. The Kirateshwar Mahadev Temple, for instance, is mentioned in the Mahabharata. Of the 75 existing Buddhist monasteries, the earliest was built in the 1700s. Many Hindu temples were built in the late 20th century; a few of these are run by the Indian army. We were told Sikkim has about 200 priests employed in temples and 500 working independently.

The Sikkim government has been building new temples in order to project the state as a religious tourism destination, taking advantage of its pleasant climate, spectacular scenery and absence of significant communal strife. The government’s amply-funded Ecclesiastical Affairs Department finances and promotes temple-building projects and improvements to Buddhist monasteries. It also oversees the general external affairs of all the state’s religious institutions. Its next big project is a complex based on the events of the Ramayana.

Kangchenjunga

At 28,169 feet, Kangchenjunga is the third highest mountain in the world. The name means “Five Treasures of the Great Snow,” a reference to its five peaks. Local people of all communities, especially the Buddhists, hold the mountain in reverence as the abode of their guardian Deity, Dzo-nga, whose benign watchfulness and protection has long ensured peace and prosperity for the people of the land. In fact, Mount Kangchenjunga is considered so sacred that the early mountaineering expeditions to it went only up to a few metres below the peak, leaving the summit untouched so as to not violate its sanctity.

The American author Mark Twain wrote about the mountain when he visited Darjeeling, a hundred miles south of Gangtok, in 1896. In Following the Equator, he humorously recollected, “I was told by a resident that the summit of Kinchinjunga is often hidden in the clouds, and that sometimes a tourist has waited twenty-two days and then been obliged to go away without a sight of it. And yet went not disappointed; for when he got his hotel bill he recognized that he was now seeing the highest thing in the Himalayas.”

Soldier saint: Temple to soldier Harbhajan Singh near the India-China border

Gangtok and Environs

Gangtok, Sikkim’s capital, is a beautiful city with many views of Kangchenjunga. During our visit, the peak was frequently visible, especially on our way up to Hanuman Tok (tok means “temple”), which sits grandly at an elevation of 7,200 feet and is approached by walking up a few hundred stairs. Local accounts say that when Lord Hanuman was flying with a life-saving herb, sanjeevani, to Sri Lanka to restore the life of the mortally wounded Lakshman, the younger brother of Lord Rama, He rested for some time at the spot where the temple now exists.

A red stone marking the spot was worshiped by the local people for centuries. In the 1950s, a government officer named Appaji Pant had a dream instructing him to see that a temple was built here for Hanuman. At some point, the red stone was sent to Jaipur to be carved into a murti of Hanuman, the one now worshiped in the temple. In 1968, the entire area—just 50 miles from the Chinese border—was handed over to the Indian army, including the temple.

The temple is staffed by Indian army personnel along with a priest on the army payroll. At the time of our visit, the hired priest was on leave, and the aptly named Hanumanthappa, a friendly young soldier in uniform, was performing the temple duties. He and four other soldiers of Army Company 362 manage the day-to-day affairs of the tok and perform the daily pujas. They were selected for these duties based on their personal devotion to God, knowledge of puja and singing abilities.

Hanumanthappa related a story well known to the Indian soldiers stationed along the border: “Besides this Hanuman temple here, the army in Sikkim maintains two temples at Nathu La dedicated to Baba Harbhajan Singh, a Sikh soldier who died in this area during the 1965 Sino-Indian conflict. Both are quite famous, and the main temple of the two is much larger than this Hanuman temple. Harbhajan Singh lost his life in a snowstorm while carrying supplies to a remote outpost. His body could not be located until he appeared in a dream to a friend and disclosed where his body and rifle could be found. After this, something strange and miraculous started happening at that area on the border. If a soldier was not performing his duty properly, an invisible hand would come and slap him. Soon it was realized that this invisible hand was that of the martyred soldier Baba Singh—still on duty, working for the safety of India. This has been going on now for 45 years. The army treats him as someone still on active duty, pays his salary to his family and even sets aside a vacant chair for him at meetings. Every soldier who is posted on this border first visits Baba’s temple and prays to him. There are many beliefs and legends among the local people about the miraculous powers of Baba Singh.”

RAJIV MALIK

Sikkim Sangeetalaya, a classical music and dance school; Shekhar Nath Upadhyaya Niraula, chief priest of Shri Siddheshwar Shiv Mandir, Gangtok

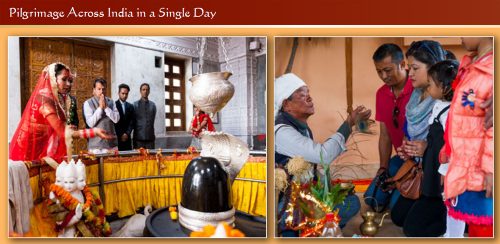

From the smaller but more popular Ganesh Tok, one can see not only Mount Kanchenjunga but also Gangtok, Darjeeling, Nathu La Pass and Kalimpong town. The same government officer, Appaji Pant, whose dream resulted in Hanuman Tok, also had a dream about this temple. In both places, small existing shrines were enlarged. Over time people felt the Deities had become quite powerful, as their prayers were being answered. With government support, the Gansha temple was enlarged and a bigger Deity installed in 2007. The temple now receives 100,000 devotees a year. Nepalese, Lepchase, Bhutias and Tibetan Buddhists alike visit and pray here, and there are Buddhists on the temple management committee. The chief priest, Bhawani Prasad Neupane, told us the temple’s biggest festival is Ganesha Chaturthi, though they do not do immersion of small Ganesha statues as is done elsewhere in India. Weddings are performed here in the Nepalese style, and in fact one was going on during our visit.

Gangtok, the Capital

Through the heart of Gangtok city runs the Mahatma Gandhi Road (MG Road). A huge statue of the Mahatma greets one at the road’s entrance. Another monument overlooking the area is the Statue of Unity, comprising figures of Bhutia and Lepcha leaders. MG Road is Gangtok’s main shopping area, home to several banks and popular restaurants as well as shops selling all kinds of goods, including Sikkim’s famous tea. Closed to vehicular traffic, the road has benches on the sides where people sit to relax or use the free wifi provided by the government. It is like a perpetual mela or fair, but spotlessly clean and smoke free. Brightly lit after nightfall, the area attracts large crowds of locals and tourists. One also encounters Buddhist monks and an occasional Hindu sadhu.

We visited several temples in the area around MG Road. The Shri Siddheshwar Shiv Mandir is located in an area known as Pani House. A natural stone Sivalingam here has been worshiped from ancient times. Murtis of Kali, Lakshmi and Saraswati were installed in 2002. The chief priest, Shekhar Natha Upadhyaya Niraula, age 50, said 25 to 100 devotees come daily, while thousands come for major festivals such as Mahasivaratri. His family hails from Nepal, and most of this temple’s devotees are Nepalese, though Buddhists also worship here. As with other temples, this mandir is being renovated with help from the government.

Gangtok’s Durga Mandir, Pandit Tara Prasad Sharma tells us, was established in 1986. He laments that while the temple is busy on festival days, on a day-to-day basis Hindus here do not set aside much time for religious activities. His attempts to set up regular Gita classes have been unsuccessful, in part because travel in this hilly area is difficult even for short distances, plus people don’t like to go out when the weather is cold or the sun has set early. He encourages devotees to visit places such as Vrindavan, Haridwar and Varanasi, where they can see how people spend time in devotion to God. Pandit Sharma said it is difficult to encourage people to be vegetarians and not get addicted to tobacco and liquor. He is regularly asked if it is possible to waive their 13-day restriction against meat and liquor after a death in the family. The weather here poses another problem—how can he perform puja in the required veshti, a single cloth, when it is freezing cold? “The climate here is not just affecting the lifestyles of the people but their religious life and practices as well.”

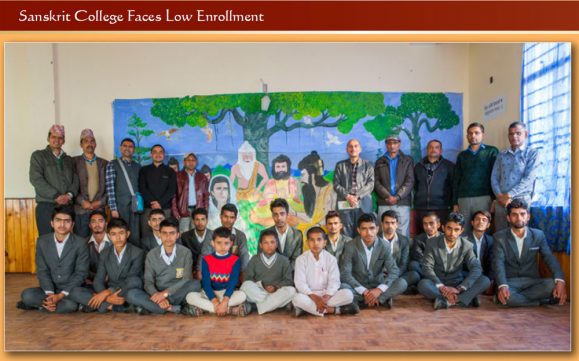

Sanskrit College: Teachers and students pose for our cameraman at the government school

Saraswati Dolma, founded in 1985, is one of Gangtok’s more unusual temples. Housing both the Hindu Goddess Saraswati and the Buddhist Deity Jetsun Dolma, or Tara, it is popular with Hindus and Buddhists. Students especially flock here to worship Saraswati, Goddess of Learning, before exams.

It was unfortunate to see that the Thakurbari Temple, dedicated to Lord Rama, Lakshman and Sita, has fallen on difficult times. It was established in 1935 by the then king of Sikkim, but recently a major renovation project stalled and the worship is being done in a makeshift shrine.

The well-equipped buildings of the Sikkim Government Sanskrit College sit impressively on a large plot of land in Samdong, about 19 miles west of Gangtok. Students and faculty wear Western-style dress; I was told that wearing typical Indian dress would be taken as a sign of backwardness by the locals, and is off-putting to potential students. The college enrolls all castes, offering nearly free education. Past graduates have included many girls, though currently no girls are enrolled. In fact, we soon learned that enrollment is so low that this prestigious institution is on the brink of closure. Though the college has facilities for 350 to 400 students, only a tenth that many are enrolled. Due to the uncertain career opportunities for Sanskrit scholars, parents in Sikkim do not want to send their children here.

Dr. Yugal Prasad Nepali, head of the college, has surveyed a dozen smaller Sanskrit pathasalas or schools in Sikkim and found the situation similar at each: a lack of interest in Sanskrit studies. While the government continues to support the college, there is obvious concern that they could one day face closure.

Dr. Nepali hopes our coverage in HINDUISM TODAY will help the institute survive, both by encouraging parents to send their children here and by pressing the central and local governments to fund more jobs in the field of Sanskrit. Everyone here loves the Sanskrit language and the Indian cultural heritage, and they are working together to make the school a success.

We met with C.P. Dhakal, president of the local branch of the Chinmaya Mission, at his home in Gangtok. He is the government’s special secretary in the tourism and civil aviation department. Dhakal is locally famous for helping Sikkim win an award presented by Prime Minister Modi in 2015 for Gangtok as the Cleanest Hill Station and Sikkim itself as India’s Cleanest State. He said the award came after a sustained campaign by students, police, business people and the general population. “Due to this award,” he said, “we received worldwide exposure and the tourist flow to Sikkim improved substantially.” Dhakal is also responsible for the Kailash Mansarover Yatra, organized by the Indian government, which goes through Nathu La Pass. That pilgrimage route is presently closed due to heightened tensions with China.

“We started this local chapter of Chinmaya Mission in 1995,” Dhakal explains. “Our brahamachari Smaran Chaitanya and I conduct classes in Bhagavad Gita. We have several hundred students, and in this way we propagate Sanatana Dharma. We’ve been allocated land for a meditation center and hope to build that in time to come.”

With regard to the Sanskrit College, he pointed out that this year there has been a five percent decrease in enrollment in all schools in Sikkim, a result of families having fewer children. He noted in passing that if a youth from Sikkim is admitted to a prestigious university in the West, the government will pay for the entire education.

Dhakal expressed concern about the conversion of Hindus to Christianity. He blames this on a failure to properly understand Hinduism. He is not too worried, however: “The British ruled us for 300 years and could not convert all of us. Today there are Hindu temples being built in Britain costing millions of dollars. So it is some sort of cycle which keeps on moving, and our Sanatana Dharma by and large remains unruffled by all this.”

Sixteen Pilgrimages at Once

Siddheshvara Dham is the government’s flagship religious tourism project. It is popularly known as Char Dham because of its replicas of four of India’s most famous temples. Located near Namchi, 50 miles southwest of Gangtok, it is a slow and rough drive over poor roads—and very cold if traveling after dark. Only in its last few miles, from the helipad—where the VIPs arrive in Namchi—to the temple, is the road in good shape.

“The British ruled us for 300 years and could not convert all of us. Today there are Hindu temples being built in Britain.”

C.P. DHAKAL

Approaching Namchi, one first encounters the world’s largest statue of Guru Rinpoche—118 feet—completed in 2004. It joined other important Buddhist pilgrimage destinations in the town, such as the Namchi and Ralang monasteries. A little farther on, the seven-acre Char Dham sits atop Solophok hill, overlooked by a 108-foot statue of Lord Siva. It is believed this place was known in ancient times as Indrakil mountain, mentioned in the Mahabharata as the place where Arjuna got the blessings of Lord Siva to obtain the divine weapon Pashupatastra, which Arjuna alone could wield and which was needed for winning the Mahabharata war. Prior to the creation of the present project there was a small Siva temple on the property.

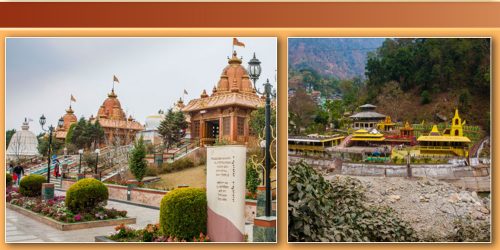

Siddheshvara Dham’s 19 temples include replicas of the Char (four) Dham: Badrinath in north India, Jagannath on the east coast, Dwarka on the west and Rameshwaram next to Sri Lanka, along with replicas of the twelve Jyotirlingam temples, which are likewise spread across India. Pilgrimage to all these destinations is thought to help one attain moksha, liberation from rebirth. Whether that’s true for these replicas is as yet undetermined. But each was built according to Vastu Shastra and consecrated in its own right as a temple, and each of the Char Dham replicas is overseen by priests appropriate to the original temple’s tradition. The twelve Jyotirlingam temples are identical from the outside, as it was not feasible to copy the temples themselves, but inside each the Sivalingam shrine is a faithful replica of the original.

The Siddheshvara Dham project was conceived by Sikkim’s chief minister, Pawan Chamling (whose home town is Namchi) as part of the larger program to promote religious tourism in the state. On its completion in 2011, the project won an award from the Centre’s Ministry of Tourism for Most Innovative/Unique Tourism Project. It has proven quite popular; during the tourist season it attracts up to 2,000 visitors a day.

Overview of the Complex

We were fortunate during our visit to be spotted by the elegantly dressed Pandit Mohan Timsina, coordinator and priest of the Siddheshvara Dham project, who proceeded to give us a grand tour. He took us first to the Kirateshwar Temple replica, which is independent of the Char Dham and Lingam temples. It enshrines an imposing 18-foot statue of Lord Kirateshwar, a popular local Deity regarded as an incarnation of Lord Siva. Thapa Singh, 65, of the Nepalese Rai community is the priest here. Very popular with devotees, he exudes a distinct divinity and conducts the pujas according to his traditions of Kirat worship.

The four largest temples reasonably match the originals in design, though of course on a much smaller scale. Rameshwaram alone, for example, is a huge temple enclosing 15 acres, twice the size of this entire Char Dham complex. The interior shrines do faithfully follow those of the original temples, and the priests conduct puja in the same manner. Twenty-five priests serve here, all employed by the government of Sikkim. They begin their day with a group meditation together, something we had not heard of at other temples in India.

The complex, designed to be wheelchair accessible, includes a vegetarian restaurant, guest house and huge parking area. There is also a covered yagna shala for fire worship, where a marriage was taking place during our visit. In addition to marriages, the temple trust organizes sacred thread ceremonies, preaching of the Bhagavat Purana and community feedings. All major Hindu festivals are celebrated here. Maha Sivaratri, the most popular, is attended by thousands of people from all the local communities.

The pilgrims we spoke with were deeply affected by the temple complex and its stunning setting. They all spoke of how peaceful and calming it was for them. Thomas and I were impressed and left this place with a sense of immense gratitude and satisfaction.

Siddheshvara Dham: Towering statue of Lord Siva overlooks the complex of temples; the original Kirateshwar Siva temple located in Legship on the Rangeet River

Kirateshwar Temple

From Char Dham we took the rough two-hour drive to the last major temple we would visit: the original Kirateshwar temple located alongside the Rangeet river 25 miles northeast of Namchi. This temple, one of Sikkim’s most ancient, exemplifies the communal harmony reigning here: the grounds include a small Buddhist temple that attracts a large number of local Buddhists. As with nearly every temple we encountered in Sikkim, the scenic beauty of the surroundings is breathtaking.

The main object of worship here is an unusual Sivalingam located in a cave area of the temple, with a kind of water spout with which one can pour water over it. The Lingam is believed to have been placed here before the time of the Mahabharata. The temple’s young priest, Nandu Sharma, 28, of the Kashyap brahmin lineage, relates the story that at one point Buddhists wanted to possess the powers of this Sivalingam and took it far away to a Buddhist monastery. Miraculously, the Sivalingam returned on its own to this temple. It was taken a few more times and mysteriously returned again each time until the Buddhists gave up. Unlike the priest of Char Dham’s Kirateshwar Temple, Sharma is not of the local Kirat community.

On normal days, this temple does not receive many visitors. But at festivals, not only Hindus but Buddhists too—understandably appreciative of the Sivalingam’s power—come in large numbers. This is known as a wish-fulfilling temple. Sharma tells us it is popular with young lovers who want to marry against their parent’s wishes.

Conclusion

Hinduism and Buddhism here in Sikkim coexist harmoniously, with devotees enthusiastically visiting the holy places and celebrating the festivals of both religions. I was struck by the happy, smiling faces and open-heartedness of Sikkim’s people. Almost everyone I met gave the impression of being in a state of meditation or just coming out of one. There is something in the Himalayan air of this erstwhile kingdom that infuses a kind of contentment and blissfulness. Perhaps the reverence for Lord Siva and the Buddha have deeply influenced not only the flora and fauna but all human beings who reside here. The state government is on the right track to promote Sikkim as a land of religious pilgrimage, for all who visit here can take back home with them an experience of true communal harmony—Sikkim’s premier export.

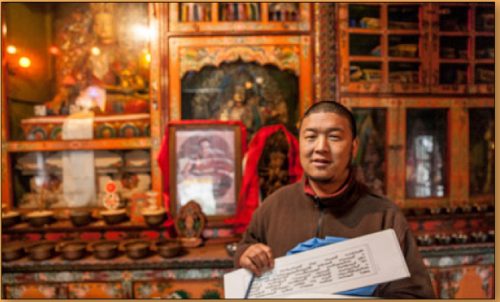

Yungdrung Kundrakling Bon Monastery

ACCORDING TO ITS FOLLOWERS, THE BON religion existed before Buddha’s time. But because it shares many characteristics with Buddhism, others claim it is a later offshoot. Communities are found in Tibet, India and elsewhere. According to Yeshi Gyatso, 32, head of the Yungdrung Kundrakling Bon Monastery in Bakkim, there are about 1,000 followers in Sikkim. Gyatso is a Lepcha, originally from Tibet, who converted from Buddhism to Bon. He explained, “Our speciality in Bon is an emphasis on emptiness and meditation. We believe in nirvana, or liberation, as well as rebirth according to one’s karma.” His monastery houses valuable Bon scriptures and has 25 students receiving both religious and secular education. He observed, “Buddhists and Hindus live amicably here. The problem is Christians with their interest in conversion and refusal to allow their devotees to pray at any Hindu or Buddhist place of worship.”

Meet the Pranami Sect

Mohan Priyacharya is the local leader of the Pranami Sampradaya, one of the larger and more influential Hindu organizations in Sikkim with many temples and chapters in the state.

WE ARE KNOWN AS KRISHNA PRANAMIS AND ARE believers of Lord Krishna. We have a group of swamis and two to three dozen pracharaks, or preachers, here in Sikkim who do katha of Bhagvat Purana and Bhagavat Gita. They educate people about Hinduism and work to ensure that Hindus remain Hindus and are not converted to other religions. We preach that first we are Hindus and then Saivites or Vaishnavites or Pranamis. We propagate Hinduism and, side-by-side, we talk about our Pranami Sampradaya and its teachings. Only when Hinduism is preserved will the various sects and our sampradaya remain in existence. We organize Janmashtami and other major Hindu festivals in a grand manner to inspire people to be connected to their own culture and keep practicing their own religion in a proper manner. We have eight temples in Sikkim, with the newest in Namphing. We train priests to perform all major samskaras, rites of passage, for our devotees. Certain elaborate rituals have been refined by us and are now performed in a shorter time. For example, our marriage ceremony can be done in one hour. We also believe the expenses of marriages should be much less.

My guru, Mangaldas ji, came to Kalimpong [now in West Bengal] in the 1940s. He traveled on foot until 1985 through Sikkim, West Bengal, Assam, Maniur and Nepal propagating Hinduism, the worship of Lord Krishna and vegetarianism. He built the Mangaldham Temple in Kalimpong, one of some 600 Pranami temples in India. We also have 150 temples in Nepal. I became his disciple in my childhood, and for the past 31 years have been engaged in the propagation of Hinduism and the Pranami Sampradaya. I have trained many brahmacharis and priests. I personally covered all four districts of Sikkim, traveling on foot to many remote places which are inaccessible by motorable roads.

Recently the chief minister of Sikkim visited the Kalimpong Temple and was so impressed he built a similar one in Sikkim to promote religious tourism. The Char Dham project, the Siddhivinayak Temple and the Sai temple were also built for that purpose.

Our founder, Dev Chandra Ji Maharaj (1581–1655), was born in Sindh. His successor, Mahamati Pran Nath (1618-1694), from Jamnagar in Gujarat, is better known today, as he wrote the 18,000-verse Kuljam Swaroop Vani. In those days of the Mughal Empire and the Muslim conversion efforts, his emphasis was on unity of religions. He talked about the whole of humanity having one God and one religion and that the message of all religions was the same. He said we should know our own self and be a good human being in this world. We emphasize meditation and teach that through meditation one will experience peace. Our message for the world is: attain spiritual knowledge, strive for devotion to Lord Krishna and perform service for your fellow human beings.

The mother of Mahatma Gandhi, Putli Bai, belonged to a Pranami family. She and the young Gandhi used to go to a Pranami Mandir in Porbandar. He mentions in his diary that during childhood he was given Pranami sanskars, and due to that influence he was inspired to work on the concept of unity of all the religions.

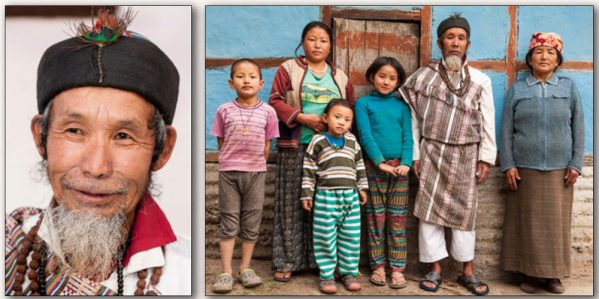

The Lepcha Priesthood

Naphey Lepcha, 70, is a leader of the Lepcha community and a traditional priest, or Bongthing. While today the Lepchas are Buddhists, they continue to observe Lepcha religious traditions. Naphey lives with his wife and four children in Kambal Basti, Samdong area, outside of Gangtok in the vicinity of the Sanskrit College. His home shrine includes pictures of Ganesha and the Dalai Lama. This interview was conducted in Nepali.

THE MAIN JOB OF A BONGTHING IS TO PERFORM PUJA FOR PEOPLE of the community. My father was also a priest, but the urge to become a Bongthing must come from within oneself. There are 20 to 30 Bongthings in Sikkim. I learned many things from my father, but there is no scripture or book we use for prayers. My name, Naphey, means someone who is recognized and considered important. It was given to me at birth. My wife’s name is Dokhet, which is the name of a Goddess. We had a love marriage around 30 years ago and I am very happy with her.

Many Lepchas became Buddhists under the rule of the Buddhist kings. I treat the Dalai Lama as our guru and believe in Lord Siva as the Creator. We believe Guru Rinpoche is a form of Siva. I know Ganesha is very generous and grants the wishes of those who pray to Him. Some of the Lepchas are Christians, and that is of their own free will. But it is unclear to me why Lepchas would convert to Christianity. Hinduism has a caste system, and therefore Lepchas cannot become Hindus. However, I have many Hindu friends.

When I work as a healer, I follow the Lepcha traditions and the way of worship known as Mun. We do not perform animal sacrifice, we light a lamp and use only flowers and fruits as offerings when we perform the puja. We first pray to nature, including the mountains, sun, moon and earth, to grant us the power to heal. If anyone is suffering, it is our duty to serve and cure that person and ensure that he is peaceful. When we are healing a sick person, no one, including the family members, is allowed to touch that person. It is through my forefathers that I have learned some mantras for healing the sick. Besides healing, I also perform puja for the peace and well-being of the ancestors.

We do not have women as Bongthings. My son could become one if he wanted to, but he has chosen to become a Buddhist lama. He was educated up to twelfth standard and had many Buddhist friends. I never wanted to interfere with his life. He is my only son and it is fine with me that he serve the people of this area as a lama. Likewise, I would have allowed him to become a Hindu priest, if he had wanted.

Community priest: Bongthing Naphey Lepcha of Kambal Vasti village with his wife, daughter-in-law and grandchildren

There are around 18 Lepcha families in this village. I conduct marriage as well as funeral rituals in the Lepcha language. We cremate our dead as well as bury them. For most cremations, the lamas do the rituals. We are invited to Hindu social occasions, such as the namakarana samskara, name-giving ceremony. If asked, I will suggest a name for the child based on the time he or she was born. Our community celebrates the festival of Tendong Lho Rumfaat, prayer to Tendong Mountain, in a grand manner. According to legend, the ancestors of the Lepchas went to the top of Tendong Mountain seeking shelter for their lives when it had rained continuously for 40 days and nights, and they were saved by the blessings of the mountain. [Similar stories of a great flood in ancient times are found on every continent]. This festival is in memory of that happening. We also worship Kangchenjunga Mountain.

I normally do not ask for money, but accept whatever is offered to me. If someone willingly offers liquor, that is fine. For my household expenses, I depend on my income from farming. We have been given a home under the chief minister’s residence reconstruction scheme. What I get as offerings for my work as a Bongthing is not more than just pocket money.

As a Bongthing, my message is that we should all live in peace and harmony. We must manage our lives within the incomes we generate. Only when people live in peace and within their means do they experience happiness. My message to the youth is that they should fulfill their karma by working hard and trying to practice truth in their lives. If they do these two things, then they will be successful and blessed.

Sikkim’s Buddhist World

Rumtek Monastery, the most famous of several important Tibetan Buddhist institutions in Sikkim, thrives again, centuries after the religion’s arrival here

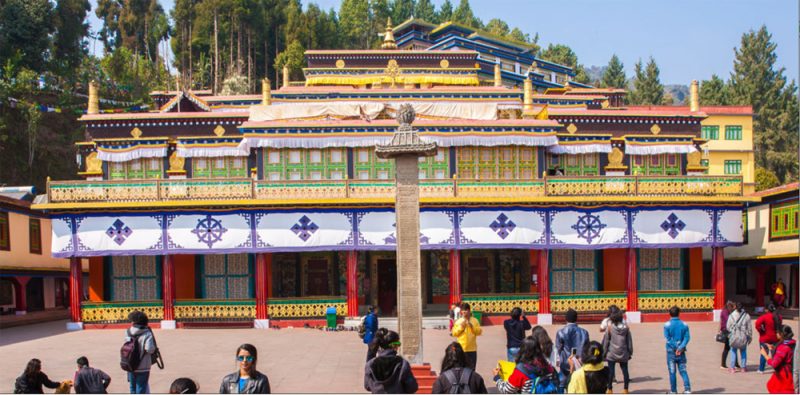

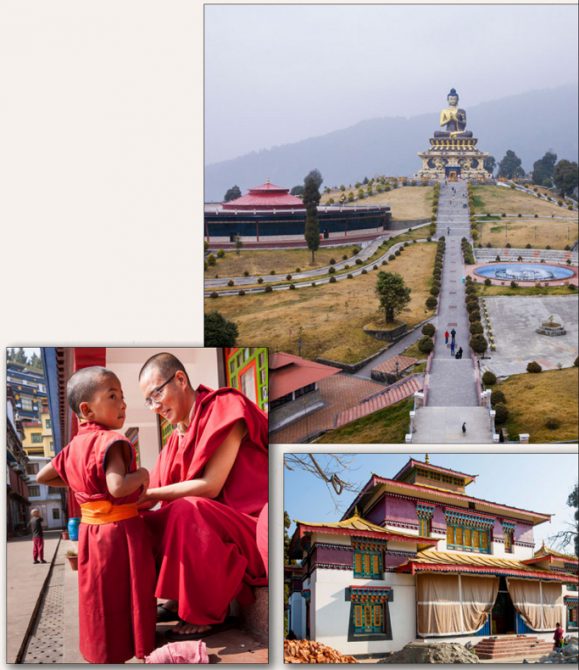

THE INDIAN STATE OF SIKKIM HAS BEEN ASSOCIATED WITH TIBETAN Buddhism for well over a millennium, and its importance in this religious tradition has increased greatly since the Chinese takeover of Tibet. Sikkim has 60 Tibetan Buddhist monasteries as well as schools and research institutes. Of those in the Gangtok area, Rumtek Monastery is the largest and finest architecturally.

Rumtek is surrounded by lush green countryside, with mountains and a river. To reach the monastery, one takes a footpath for several hundred yards. Posted alongside the path are pointed messages, such as this from the Buddha: “If you can’t be positive, then at least be quiet.” When we visited, many visitors were being taken around by local guides. We saw many monks, especially the young ones who are brought by their families, some from as far as Thailand, to be educated at the monastery. The young monks seemed to enjoy getting their pictures taken with visitors.

Originally built in the 17th century, Rumtek Monastery had fallen into ruin by the time Rangjung Rigpe Dorje, the 16th Karmapa, fled Tibet in 1959. Sikkim’s royal family and the locals helped him rebuild it. Successorship is a matter of heated dispute, and is presently before the Indian courts; the 17th Karmapa, like his predecessors, will become the owner of the monastery and its valuable contents.

On their way to or from Rumtek, tourists and devotees alike stop at the Dro-dul Chorten Stupa. Accommodating up to 700 monks and encompassing the Sikkim Institute of Higher Nyingma Studies, this was built in 1945 by Trulshik Rinpoche, head of the Nyingma school of Buddhism. We witnessed a rush of monks and devotees seeking to meet several senior lamas who were visiting.

In Gangtok itself is the Namgyal Institue of Tibetology, a museum and research institute established by the Dalai Lama in 1958, which documents the history of Sikkim’s Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. The director, Tashi Densapa, explained that the institute preserves important scriptures belonging to all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism. He and research coordinator Anna Denjongpa emphasized that a harmony exists among the various religious communities in Sikkim, in part because Buddhism is a liberal, all-embracing religion.

Visitors at Rumtek monastery; Buddha Park of Ravangla in southern Sikkim, opened in 2013; Enchey Monastery was established in 1909 with the blessing of Lama Drupthob Karpo; older monk adjusts a new one’s robes