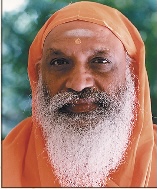

BY SWAMI DAYANANDA SARASWATI

Being a tradition, not an organized religion the Hindu Dharma is imbibed by one as one grows in a society where that tradition is alive at home and in the community. Through the various forms of culture which are not alienated from religion, one can gain a degree of appreciation of one’s religion. The religion itself is based upon its vision of human destiny, of the world and of God. Whatever one imbibes from parents and one’s community forms a part of the core person. The absence of alternative forms, which challenge one’s own cultural and religious commitment, lends stability to this core person. The core person being stable, the adult can explore further and learn, in time, the meaning of every form in all its profundity. Even if one does not have the desire or opportunity to learn, yet one can command a degree of trust in oneself, the world and God. The core person being stable, the adult can continue with the religious beliefs and forms of practice, with a sense of doing the right thing.

The child growing in an Indian home in America is not in the same situation. The home of the first-generation immigrants is more or less like one in India in terms of culture, religion, attitudes and values. But when this child is sent to a day-care center and then to kindergarten, it is bound to be confused by the inconsistency between the home and outside. Of these two, which will be more real and acceptable to the child? With television programs contributing their might through cultural forms of language, dress, food, music and so on, what is outside the home will gain better credibility. But the parents, on the other hand, are never dispensable, for they are Gods for the child, and their language, food, dress, customs and manners cannot be wrong. It is logical that the core person now faces issues of self-identity. If these issues of self-identity are not addressed, they will haunt the person not only as a young adult, but until he or she is 90 years old. Without addressing them, unfortunately some turn away from this problem of identity confusion to totally conform to the thinking and life-style of the majority. This will not help. The confusion of the core person still being there; it will control one’s life. The meaning of life is bound to be found missing. Living becomes miserable. Psychotherapy is inevitable. While therapy can help one understand the core problem, the conflict of self-identity remains to be addressed. This amounts to one’s conscious attempt to understand the parents’ culture, religion and the whole background. How?

A program of study under the guidance of someone who is well informed would be an obvious course to gain a firm grasp of the Hindu dharma in general. In the absence of such guidance. a group study of certain selected books authored by recognized scholars of this vast dharma would be an ideal alternative. The groups can also invite scholars to discuss various topics in their group meetings. Hinduism Today can recommend, after careful examination, a set of books for study.

The Vaidika Dharma allows different forms of prayer and worship. The altar of worship is also personal. This freedom comes from the Vedic vision that all that is here is nonseparate from God. God is looked upon as both the maker and the material for the creation of this world. Any created form cannot be separate from its material cause like the shirt is nonseparate from the fabric of which it is made. While God can be independent of the world, the world, on the other hand, cannot be independent of God. So every phenomenon in the world is the manifestation of God.

For a Hindu, even space can be an altar of worship. In the temple of Chidambaram, space is worshiped as the Lord–so too, time and everything else that is in time and space. Therefore, any altar, as well as any form of worship, is valid for a Hindu. In the light of this vision of God, the question of many Gods does not arise, nor is God a matter of belief. When all that is here is God, one has to understand God. I don’t believe in the existence of the world. I know that I face, encounter a world. I am within this world. I don’t believe, but know that there is a world. If that world, including my body-mind-sense complex, is God, according to the Veda, then there is a challenge for me to understand how that can be.

When we say that all forms and altars of prayer are valid, we do not mean that all religions lead to the same goal. Each world religion has its own goal. Most of them promise a heaven. By one’s own thinking, one can be away from the reality of God, even though God is everything. While any form of prayer is acceptable and valid, that itself is not the goal of a religious pursuit. It is a laudable quality to grant others the freedom to pursue their own religion, but it is important that we examine the ultimate end professed by given religions. They are definitely different. The section of the Vedas dealing with realities of living is always in the form of a dialogue. Even an epic like the Mahabharata is a dialogue, including the Bhagavad Gita therein. This is so because the subject matter unfolded in these dialogues is one to be understood and assimilated and lived, not to be blindly believed. Questions are always encouraged, so that the understanding and assimilation of the subject matter will take place. Even an unverifiable belief is to be understood as such. The realities cannot be a matter of belief. What is believed can be false. Reality is always to be understood, even though one may believe it to be true pending understanding. When this is the Hindu tradition, how can one resist its invitation to a dialogue?

Swami Dayananda, 67, a sannyasi of the Adi Shankara and Veda Vyasa tradition, founder of Arsha Vidya centers in India, Canada and Australia, has taught throughout the world for over 30 years.