By CHOODIE SHIVARAM, BANGALORE

Miss world ’96 beauty pageant is now over. The world beauty was crowned on November 23 in Bangalore, India, before a live TV audience of 2.5 billion viewers in 120 countries. The other 87 pretty representatives returned to their countries. All the noise and flurry has died down. The newly anointed Miss World, Irene Skliva of Greece, us$80,000 and many perks richer, is rendering service under the banner of “Beauty with a Purpose.”

What remains behind are the issues the pageant raised. Thousands of women (and men) across Bharat protested, calling the beauty pageant “demeaning to our culture,” “devaluing to our tradition,” “promoting vulgarity and obscenity,” and “a disgrace to womanhood.” An equal number of eminent persons–women and men–from the field of cinema and art supported the pageant with a cocky, “What’s wrong? Such contests have been going on for years.”

Communists deplored the event as capitalist exploitation of women and part of the multi-national corporations’ carefully planned plundering of India. Women’s groups found the event degrading to women. The organizers were surprised by the protester’s vehemence, but not by the opposition, as beauty contests have been a favorite target of feminists since the 1960s.

When Amitabh Bachchan’s ABCL company announced Bangalore as the venue, complaints began. Mrs. Hemalatha Mahishi, eminent advocate and general secretary of Jagriti Mahila Adhyaana Kendram, condemned his and all such contests: “They are a disgrace to womanhood. Our women throughout the ages have been known for their prowess. Is beauty any achievement? I can understand if these women were competing with intellectual achievers.”

“Such contests do not enhance the prestige of women, but only demean them,” stated Ms. Kumidhini Patti, general secretary of All India Progressive Women’s Association, during a protest march.

“An Indian woman is a beautiful person. Her role as a mother, wife, daughter, her patience and values make her a total person. She does not let go of her family, come what may. Beauty contests judge the physical attributes of women by the Western yardstick. It’s an insult to Indian women. We cannot allow this precedent,” stated Mrs. Kamal Kanteeravaswamy, a housewife who regularly assists needy people.

Eric Morley and his wife Julia founded the Miss World pageant in 1951, and held it annually in London until 1990. Rapidly diminishing interest in England forced moves first to America, then Sun City, South Africa, and now India. The Los Angeles Times observed, “Among current sentiments is the suspicion that India has become a dumping ground for the West’s rejects, and the Miss World pageant surely fits the bill.”

This isn’t the first threat to Miss World. In the early 70s a British activist group, the Angry Brigade, planted a bomb near the event site. In the late 70s protesters stormed the stage at the pageant finale at London’s Royal Albert Hall. Continued pressure from feminist groups has forced a recasting of contests in the West as a judging of talent, intelligence and accomplishment, as well as beauty–whence the new Miss World slogan, “Beauty with a purpose.”

Eric Morley defended his contest: “Protesters go on about culture, but it does not help to have a closed society.” His wife, Julia appealed to them, saying, “There’s a purpose behind this pageant. Let’s give up this rebellion and join hands.”

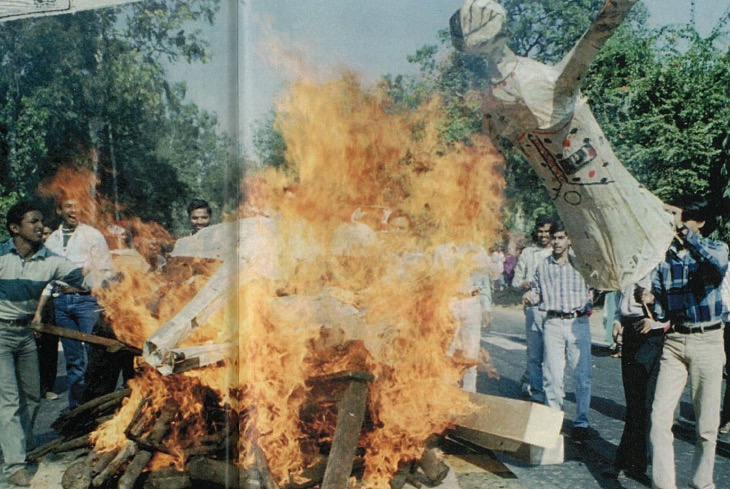

But the protests only heated up. Various factions ranging from rightist groups to extreme leftists, youth organizations and voluntary societies joined to voice their protests. Akila Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, the BJP youth wing, went from college to college condemning the pageant as “a cultural invasion and promotion of Western concepts of beauty, degrading to our women.” Bangalore colleges and schools had to be closed for two days before the controversial event.

Matters worsened when the Chief Minister of Karnataka, instead of ironing out the differences and coming to an understanding with the protesters, resorted at public functions to scathing verbal attacks on the protesting women. He even stated at one point, “If women want to show themselves in the nude, let them, and let those who want to see, see.” In fact, it seemed as if the government was a de facto sponsor of the event, which irked many protesters.

Dismissing a court challenge to the contest by Mahila Jagran Samiti (Forum to Awaken Women), Bangalore Justice S. Rajendra Babu lectured: “Coming as you do from the land where there is worship of nude women by tantrics,…where erotic sculpture is part of traditional temple architecture, where Vatsayana wrote on the art of love in the Kamasutra, necessary sense and sensibility regarding culture and decency–to discern between art and beauty on one hand and obscenity on the other hand–should always be maintained.” One high court judge told Hinduism Today during an informal chat, “These women obviously did not come up with an intelligent, coherent argument against the contest.”

With this, clear battle lines were drawn between the government and the protesters. Kinay Narayana Sashikala of the Mahila Jagran Samiti announced a twelve-member suicide squad would immolate themselves at the pageant while the show was on. But due to the extreme police protection, or last-minute second thoughts, none did. Members did storm into a Godrej showroom and smeared cowdung on the equipment. An unknown (and likely fictitious) group calling themselves “Indian Tigers” threatened bomb attacks. BJP parliamentarian Uma Bharati threatened, “We will give our lives, we will take lives, but we will not allow the show.” On November 14 India was stunned by the self-immolation of 24-year-old Suresh Kumar. He lit himself afire in front of hundreds of people at the Madurai train station while shouting anti-pageant slogans. He was a member of the Marxist Democratic Youth Federation. His death especially shocked the event organizers.

Additional security forces were called, and 12,000 police personnel posted for duty in Bangalore–at a cost to the event of more than us$1 million. Section 35 of the Police Act, prohibiting assembly of four or more persons, was invoked–a law meant for times of severe unrest and rioting. “This was required in the wake of threats to disrupt the pageant, and also the safety of the contestants who had come from different countries,” said the police commissioner.

More voices joined in chorus. About 10,000 women from all over India came to Bangalore and took out a march from the city railway station. “Some groups from outside India wrote to us expressing solidarity,” reported Mrs. Nesargi. The city witnessed a host of seminars and panel discussions by both pro- and anti-pageant activists. Television channels were full of interviews and discussions on the issue.

At a seminar organized by the All-India Mahila Samskritik Sanghatan, prominent personalities from the fields of law, literature and science spoke against the contest. A literary figure and former chief justice of Karnataka, High Court nonagenarian, Nittor Srinivasa Rao, expressed full support to the protest, and said, “Contests based on the attraction of a woman is unacceptable to the country.” Among those who also raised their voices were former chief justice of India, M.N. Venkatachaliah, E.S. Venkataramiya, former supreme court judge V.S. Krishna Iyer, Magsaysay award winner K.V. Subbanna, the doyen Kannada poet, Pu. Thi. Narasimhachar, prominent literary figures A.N. Murthy Rao and Channavira Kannavi.

To counter growing opposition, ABCL put forth a survey report supposedly conducted by a reputed institute of management showing Indians were mostly pro-pageant. The pageant-supporting All-India Mahakal Bhakta Mandal had a special puja performed for eight days at the Mahakaleswar temple in Ujjain for the pageant’s success.

Says Mark West, South African film maker who bought the TV rights for the pageant, “I simply cannot understand how a 2,000-plus year-old culture can be destroyed by a two-hour entertainment program. This event is too small a thing to make a impact on this ancient culture. I have been to a few Indian movies and there is far more nudity and obscenity in them than in our beauty contest.”

Countering these views, justice M.N. Venkatachaliah cautions, “The rationalist are trying to justify obscenity. We should remember that our country has been known for its ideals and spirituality. Yes, society should be open, but not permissive. Conventional values must be maintained. Ours is a duty- and obligation-based society. Degeneration of values will lead to moral instability and destruction.”

Many pointed out that when Sushmita Sen and Aishwarya Rai both won world beauty contests in 1994, India celebrated wildly. Mrs. Mahishi countered, “All these years we would watch Miss World on television and forget about it after a few hours. It was inconsequential. But when the big event comes right to our doorstep, it is bound to influence our youth. Our girls will become more fashion conscious, and this will find its way into their lifestyles. These wrong values will tear our traditional culture and spell danger. The consequences of this pageant can already be seen in advertisements now. They are more bold than before.”

“Today it’s Miss World; tomorrow it’s electrolysis, liposuction, artificial eyes and face-lifting,” said BJP state legislator, Pramila Nesargi. “The West wants all women to look alike, and the only way to do this is with makeup and surgery.”

While some women’s groups were crying foul about culture, a number of organizations and intellectuals were opposing the pageant as it promoted “commodification of women,” and entry of multi-national companies whom they called, “imperialists.” “Women are being used as raw material to promote a product. They say ‘Beauty with a purpose,’ but what is the purpose? Godrej co-sponsored the Miss World program to launch a new product. The first thing they did after the event was to get Miss World to model for their product in Bombay,” stated Mrs. Mahishi.

Amitabh Bachchan Corporation Ltd. promised that this ten-crore-rupee event would showcase India and launch Bangalore on the global pathway. I attended all the events and later watched a re-telecast of the final show. I heard some people in the audience commenting, “Our local programs are better organized.” Obviously, they left disappointed–most people had paid dearly for the tickets. For all the media hype and publicity it received, the final show was nothing more than a colorful entertainment program. I noticed the event did nothing to project Bangalore to the world, and the backdrop of Hampi (the Vijayanagar empire), though well done, failed to impress.

Renowned dancer Mallika Sarabhai described the cultural show as “Bollywood culture of India,” and regretted that such an opportunity to showcase India and its culture to the world was lost.

I found that the last round of questions, which judged the five semi-finalists, were the same that were asked the previous day at rehearsals. I saw truth in the statement of Vimochana, “Beauty contests and the hype around them not only convey the idea that beauty is an achievement (rather than a happy accident of birth), but a privileged achievement superior to accomplishments in various fields of work. Compare the publicity and rewards given to beauty queens to the scarce notice taken of women who have won prestigious international awards for their exceptional work or performance in a variety of professions and activities.”

The protests no doubt dampened the show for the organizers. They faced a disaster had any of the threats of self-immolation been carried out at the final show telecast live around the world. Several international publications noted that India was only learning that beauty pageants attract protests–the Los Angeles Times, for example, headlined their piece, “India Sees Ugly Side of Pageant.” The Washington Post said, “India’s feminists, asserting arguments also made in Western countries, said that such pageants demean women by turning them into commodities.”

The other day I watched a little five-year-old girl on television saying she wants to be a Miss World like Aishwarya Rai. I spoke to a group of college girls who admitted that they were a little more bold in their fashion after seeing all the beauties. “What’s wrong in it?” they asked me.

Beauty pageants may come and go, but the issues they raised cannot be ignored. We note that most of the countries of the world have either shown the door or outright rejected such beauty contests. At least in a land where Manu had written, Yatra naryastu pujyanthe, ramanthe tatra Devatha–“The Gods are pleased where the women are held in esteem,” let the women’s voice be heard.

SIDEBAR: IT’S HARMLESS – IT’S DANGEROUS

IT’S HARMLESS

Fanatical reaction has hurt Hinduism

Religiously healthy Hindus don’t share the protester’s reactionary sense of moral outrage at such an innocent activity. Objectors claim the contest reduces women to sex objects and condemn it as a flesh market. India has participated in such contests for decades, without perverting the morals of its society. This unknown coterie of women was seeking nothing but publicity for threatening suicide over this pageant. The media has given them excessive publicity, fueling their fanaticism and needlessly hurting the fair name of Hinduism.

Perhaps a few of these pageants are mere “cattle parades,” with only the physical aspect receiving attention. However, the intellectual, cultural and personality factors are evaluated in many such spectacles, and high standards of behavior are upheld. There’s nothing inherently immoral in adjudging beauty. To admire feminine beauty is not to ogle at girls. The judges themselves are normally qualified people, not lay lechers. Glitter and glamour eventually end, but they therefore cannot be ignored. To behave as if they do not exist, simply because they do not persist, is wrong. Femineity and grace endure, and contestants ought to be judged on these aspects, too.

All of life is to be enjoyed. “Pleasure as such is not to be condemned,” writes the greatest Hindu savant, Dr. S. Radhakrishnan, former president of India.

In matters of sex, Hindus as a rule avoid the extremes of prudery and prurience. Dr. Radhakrishnan approvingly quoted Havelock Ellis’ statement that in India “sexual life has been sanctified and divinized to a greater extent than in any other part of the world. It seems never to have entered into the heads of the Hindu legislators that anything natural could be offensively obscene, a singularity which pervades all their writings, but is no proof of the depravity of their morals.” Thus these protesting Indian women are not in the Hindu tradition.

Ramesh D. Jethalal, Journalist, Durban, South Africa

IT’S DANGEROUS

Pageants increase oppression of women

Arguments for and against beauty contests are presented in the Indian media as a case of international cultural modernizers fighting swadeshi votaries resisting cultural invasion. They are alternatively described as resulting from an aesthetic repugnance for the vulgarity or supposed immodesty of the entire exercise. It is possible that the spectacle of an ageing Bollywood megastar, in his recent reincarnation as trendy impresario peddling this kind of soft and brash entertainment, may be distasteful and even slightly degrading.

But the substantive opposition to the Miss World contest is much more serious, and has nothing to do with spurious ideas of national culture, nor does it lie in moralistic sermonizing on the extent of clothing that should cover the female body.

The Miss World contest and similar competitions are fundamentally objectionable because they seek to create and to perpetuate notions of female desirability which are actually oppressive and restrictive for most women. If earlier, more traditional societies created unfortunate stereotypes of women as self-sacrificing and subordinate housewives, the new role models of glamorous playthings are no less limiting, and indeed may go further in preventing the possibility of true equality between the sexes. When these images are relentlessly purveyed, not only by the media, but even by politicians and others, they can have very detrimental effects on the life changes of young women. These women may fail to realize their potential, not only because of the many constraints society overtly places on them, but because their own aspirations have been colored by such representations.

Jayati Ghose, Frontline Magazine, Chennai, India