He strode powerfully along the roads and fields of his island each day, and those who saw him coming would move warily to the other side, avoiding the man whose look and voice could pierce the soul and shake the spirit of anyone he met. The white-haired, dark-skinned sage knew their thoughts, and sometimes spoke them aloud. He saw their future, and not infrequently intimated what lay ahead. If you didn’t want to know your inmost Self, you didn’t want to meet Yogaswami on the roadside.

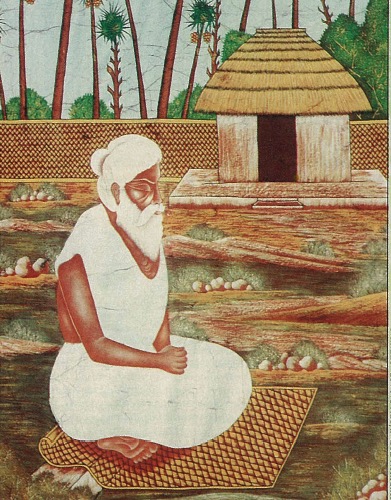

He dressed in white and lived simply, immersed not in things of this world but in an expanded consciousness of the timeless, formless, spaceless Self, Parasiva. Hindus, Christians, Buddhists, Muslims and even atheists sought his wisdom, whether it be delivered with heart-melting love or heart-stopping power. It was 125 years ago that Sage Yogaswami, the satguru of Lanka’s Tamil Hindus for half a century, was born. Inwardly, it is believed, he continues to guide his followers, now scattered around the globe.

He is mother, father and guru: Each morning in his austere hut with its cowdung floor, Yogaswami would rise before the sun and light camphor to drive the night outside. His only worship was conducted at a small shrine which held the holy sandals of his satguru, Chellappaswami. He would offer a few flowers to the tiruvadi, and light an oil lamp. Soon devotees would arrive, eager to catch him early before he marched out on the roads, for he would daily walk 20 to 40 miles, alone. He continued this regimen into his eighties. Devotees would quietly come forward, touch his feet and sit on the mats. At his gesture they would sing, usually from the Thevarams and other Tamil scriptures and mystic poems.

A Sri Lankan teacher, the late Tiru T. Sangarappillai Thirunelveli, vividly remembered the ashram during its height in the 1940s and 1950s. “I used to go early in the morning. I would see hand carts, bullock carts and motor cars all lined up on the road. Many would come out bearing fruits, fruit trays and paper bags. Others would enter, taking milk and fruits. On one side people would worship. On the other people would chant the Tamil Vedas. People would wait patiently outside unable to enter. Inside people would be seated in silence. Such was the sight of the devotees. He would shower his grace on each one. He would sit in perfect silence; then he would sing. He would ask the devotees near him to sing. On many occasions I stayed the night. At times we could sleep only after midnight. Even then, Gurunathan would wake up by four, perform his ablutions and sit in deep meditation. After his meditation, he would worship God with divine songs. In this way his humble ashram slowly became known as a temple to a living God.”

You are not these flesh and bones: Sage Yogaswami passed his early days in search of God, and lived his later life in union with Him. His devotional and contemplative nature blossomed early on. Even in his childhood, he rushed to the temple, cried tears of joy during worship and eagerly undertook penance, such as rolling around the temple in the hot sun. As a young adult, he vowed himself to celibacy and renounced a place in his father’s business because it did not allow him time to meditate and study the scriptures he loved so deeply. Around 1890, he found a quiet job as a storekeeper for an irrigation project in Kilinochchi. Here, he lived like a yogi, often meditating all night long. He demanded utter simplicity of himself, and purity. Purity would be what he later called all his devotees to achieve–in mind, speech and action. What appeared to others as incomprehensible austerities were, to Yogaswami, natural, necessary and even blissful strivings which brought him ever closer to God, who he called Siva. Yet, all of this was just a rudimentary preparation for the life he would live with his satguru.

Yogaswami’s satguru, Chellappaswami, was intense, unpredictable, unfathomable. Once Yogaswami related to a devotee, “If it were you, you would not have lasted one day with Chellappa.” Yogaswami lived over five years with him, from 1905 to 1911. At another time, a devotee said to Yogaswami, “Chellappaswami has gone away, but he gave everything to you.” Yogaswami at once clarified the process of his guru’s “giving.” “Did I receive it freely?” he retorted. “I obtained it by digging up a mountain!” Chellappaswami’s outward appearance was of a rumpled vagrant. He would speak to himself and shout at those who passed by. He ate with the crows. Very few people recognized or acknowledged his divine stature. Thus, when Yogaswami began to follow Chellappaswami as a disciple, he was also deemed a madman, a guise not uncommon among masters of the Natha Sampradaya.

Yogaswami knew, however, that the day-to-day life that most people led could not give him the truth he sought. With his guru, he joyfully denied himself the most basic of physical needs, including food, shelter and sleep, and ultimately transcended all of them. After Chellappa’s passing in 1911, Yogaswami spent years of intense tapas under an olive (illuppai) tree. The junction at the illuppai tree was well trafficked, so Yogaswami always had stones at his side to pursuade loiterers to move on. His practice during this period was to meditate for three days and nights in the open without moving about or taking shelter from the weather. On the fourth day he would walk long distances, returning to Columbuthurai to repeat the cycle.

After some years, Yogaswami allowed a few sincere seekers to approach. They worried that his sadhanas were too severe, and urged him to take care of himself. Eventually, they persuaded the yogi to move into a nearby one room thatched hut they had built for him. Even here he forbade devotees to revere or care for him. He prohibited anyone even to rethatch the roof. His closest followers would do so only when he was away, being sure to be finished before his return. Holding fast to his self-reliance, he would not even permit a lamp to be lit by another person. Day and night Swami was absorbed in his inner worship, guiding the karmas of thousands, down to every detail of a marriage proposal, a health problem or a close follower’s business transactions. Politicians would always fall at his feet before embarking on their work. Every Sivaratri he would meditate through the entire night. Devotees described seeing brilliant light in place of Swami’s body on these nights. Others were amazed to see him sit statue-like for hours on end. On one occasion which he liked to recall, Swami was seated in perfect stillness, like a stone. A crow flew down and rested several minutes on his head, apparently thinking this was a statue.

Soften your heart and let it melt: As the years passed, Swami relented a little, permitting his ever-increasing fold to express their natural devotion. He allowed his hut to be cleaned, the snakes removed and a new cow-dung floor installed.

Yogaswami was equally feared and loved. Even his ardent devotees approached him with trepidation, for he somehow always knew their innermost thoughts and feelings–the good and otherwise. If their motivation was not pure, he would berate them or pelt them with stones or see they never entered his gate. He was not a stranger to rough language, using it to keep the wrong people at bay. When one of his disciples complained about his sometimes incendiary temper, he replied, “Is not a big fire necessary to burn so much rubbish?” Still, even those he rebuked felt blessed, reckoning it a spiritual cleansing. Susunaga Weeraperuma, a Sinhalese Buddhist, recounted that in his first meeting, “Yogaswami was sweeping the garden with a long broom. ‘I am doing a coolie’s job,’ he said. ‘Why have you come to see a coolie?’ He chuckled with a mischievous twinkle in his eyes. I interpreted his words to mean, ‘I am a spiritual cleaner of human beings. Why do you want to be cleansed?’ He gently beckoned us into his hut. Talking to him was unnecessary, for one had only to think of something and he replied instantaneously. Yogaswami was aware of my thoughts all the time.”

In another account, the late Dr. S. Ramanathan Chunnakam recalls a humbling lesson received in 1920. “I went to visit Swami with advocate Somasunderam of Nallur. In my youth, I was proficient in sword fighting and similar arts. As a result, I was a little arrogant. While on the way to the ashram, Swami appeared in the middle of the road and felled me. I can never forget this incident. Even marshal arts instructors cannot show the proficiency in their hands and legs that Swami displayed. After I got up, Swami took me into his hut and showered me with love. But it was only years later that I understood the divine sport that made me eat the dust on the road to Swami’s ashram.”

Contemplative contemporaries: Yogaswami revered and was deeply motivated by the other Hindu leaders of his time. In 1889, Swami Vivekananda was received in Jaffna by a large crowd and taken in festive procession along Colombuturai Road. As he neared the illuppai tree that Yogaswami later performed his tapas under, Vivekananda stopped the procession and disembarked from his carriage. He explained that this was sacred ground and that he preferred to walk past. He described the area around the tree as an “oasis in the desert.” The next day, the 18-year-old Yogaswami attended Vivekananda’s public speech. He later recalled that Vivekananda paced powerfully across the stage and “roared like a lion”–making a deep impression on the young yogi. Vivekananda began his address with “The time is short but the subject is vast.” This statement went deep into Yogaswami’s psyche. He repeated it like a mantra to himself and spoke it to devotees throughout his life.

On one occasion, Yogaswami divulged his respect for Mahatma Gandhi. He related, “Two European ladies came to see me. They had been in India to see Mahatma Gandhi and wanted a message from me. I asked them what Gandhi had told them. The Mahatma had said, ‘One God, one world.’ I told them I could not think of a better message and sent them away.” Yogaswami also met the great sage Ramana Maharshi on a pilgrimage to India.

Good thoughts: Yogaswami articulated his own teachings in over 3,000 poems and songs, called Natchintanai, meaning “good thoughts,” urging seekers to follow dharma, serve selflessly and realize God within. These gems flowed spontaneously from him, sometimes while in a devotee’s home, often seated at the small side shrine to Parvati in a nearby Siva temple he frequented. Any devotee present would write them down, and he occasionally scribed them himself [see right]. Natchintanai have been published in several books and through the primary outlet and archive of his teachings, the Sivathondan, a monthly journal he established in 1935.

These publications preserve the rich legacy of Swami’s sayings and sweet songs. The Natchintanai are enchantingly composed, and a joy to sing. Swami’s devotees soulfully intone them during their daily worship and discipline as much today as when the great sage walked the narrow lanes of Jaffna. Natchintanai are a profound and powerful tool for teaching and preserving Hinduism’s core truths. Professional, modern recordings of Natchintanai are numerous, the latest being produced in the UK early this year.

Based in pure Saiva Siddhanta, the Natchintanai affirm the oneness of man and God. Though Yogaswami dauntlessly stressed the nondual nature of Reality, he could never be labeled an Advaitic or Vedantin. He acknowledged the utmost peaks of consciousness as well as the foothills that must be traversed to reach that summit, and constantly spoke of the Nayanars, the 63 Tamil saints who embodied his Siddhanta heritage and ideals. His message was summarized by him in two words, Sivadhyana and Sivathondu–meditation on Siva and service to Siva. With these two, he ever asserted, one can complete the journey.

Don’t go halfway to meet difficulties. Face them as they

come to you; God is always with you, and that is the

greatest news I have for you.

Sage Yogaswami

A MASTERFUL LIFE

1872-1964: At 3:30am on a Wednesday, in May of 1872, a son was born to Ambalavanar and Sinnachi Amma not far from the Kandaswamy temple in Maviddapuram, Sri Lanka. He was named Sadasivan. His mother died before he reached age 10. His aunt and uncle raised him.

In his school days he was bright, but independent, often studying alone high in the mango trees. After finishing school, he joined government service as a storekeeper in the irrigation department and served for years in the verdant backwoods of Kilinochchi.

The decisive point of his life came when he found his guru outside Nallur Temple in 1905. As he walked along the road, Sage Chellappan, a disheveled sadhu, shook the bars from within the chariot shed where he camped and shouted loudly at the passing brahmachari, “Hey! Who are you?” Sadasivan was transfixed by that simple, piercing, inquiry. “There is not one wrong thing!” “It is as it is! Who knows?” the jnani roared, and suddenly everything vanished in a sea of light. At a later encounter amid a festival crowd, Chellappa ordered him, “Go within; meditate; stay here until I return.” He came back three days later to find Yogawami still waiting for his master.

Yogaswami surrendered himself completely to his guru, and life for him became one of intense spiritual discipline, severe austerity and stern trials. One such trial, ordered by Chellappa, was a continuous meditation which Chellappa demanded of Sadasivan and Kathiravelu in 1909. For 40 days and nights the two disciples sat upon a large flat rock. Chellappa came each day and gave them only tea or water. On the morning of the fortieth day, the guru brought some stringhoppers. Instead of feeding the hungry yogis, he threw the food high in the air, proclaiming, “That’s all I have for you. Two elephants cannot be tied to one post.” It was his way of saying two powerful men cannot reign in one place. Following this ordination, their sannyas diksha, he sent the initiates away and never received them again.

Kathiravelu was not seen again. Yogaswami began the life of the wandering ascetic, begging for his food, visiting temples and chanting hymns. He undertook an arduous foot pilgrimage to Kathirgama Temple in the far South. In 1910, after returning to Jaffna, two devotees witnessed Yogaswami’s “coronation.” He met with Chellappa, who greeted him, saying, “Come! I give the crown of Kingship to you!–for as long as the universe endures.”

Chellappa passed in 1911. Yogaswami, obeying his guru’s last orders, sat on the roots of a huge olive tree at Colombuthurai. Under this tree he stayed, exposed to the roughest weather, unmindful of the hardship, and serene as ever. This was his home for the next few years. Intent on his meditative regime, he would chase away curious onlookers and worshipful devotees with stones and harsh words. After much persuasion, he was convinced to move into a nearby thatched hut provided by a devotee.

Few recognized his attainment. But this changed significantly one day when he traveled by train from Colombo to Jaffna. An esteemed and scholarly pandit riding in another car repeatedly stated he sensed a ” great jyoti” (a light) on the train. When he saw Siva Yogaswami disembark, he cried, “You see! There he is.” The pandit cancelled his discourses, located and rushed to Siva Yogaswami’s ashram, prostrating at his feet. His visit to the hut became the clarion call that here indeed was a worshipful being.

From then on people of all ages and all walks of life, irrespective of creed, caste or race, went to Yogaswami. They sought solace and spiritual guidance, and none went away empty-handed. He influenced their lives profoundly. Many realized how blessed they were only after years had passed.

Yogaswami’s infinite compassion never ceased to impress. He would regularly walk long miles to visit Chellachchi Ammaiyar, a saintly woman immersed in meditation and tapas. Yogaswami would feed her and attend to duties as she sat in samadhi. Upon her directive, her devotees, some the most learned elite of Sri Lanka, transferred their devotion to Satguru Yogaswami after her passing.

He would mysteriously enter the homes of devotees just when they needed him, when ill or at the time of their death. He would stand over them, apply holy ash and safeguard their passage. He was also known to have remarkable healing powers and a comprehensive knowledge of medicinal uses of herbs. Countless stories tell how he healed from afar. He would prepare remedies for ill devotees. Cures always came as he prescribed.

When not out visiting devotees, Yogaswami would receive them in his hut. From dawn to dusk they came and listened, rapt in devotion.

In 1940, Yogaswami went to India on pilgrimage to Banaras and Chidambaram. His famous letter from Banaras states, “After wanderings far in an earnest quest, I came to Kasi and saw the Lord of the Universe–within myself. The herb that you seek is under your feet.”

One day he visited Sri Ramana Maharshi at his Arunachalam Ashram. The two simply sat all afternoon, facing each other in elequent silence. Not a word was spoken. Back in Jaffna he explained, “We said all that had to be said.”

Followers became more numerous, so he gave them all work to do, seva to God and to the community. In December, 1934, he had them begin his monthly journal, Sivathondan, meaning both “servant of Siva” and “service to Siva.”

As the years progressed, Swami more and more enjoyed traversing the Jaffna peninsula by car, and it became a common sight to see him chaperoned through the villages.

On February 22, 1961, Swami went outside to give his cow, Valli, his banana leaf after eating, as he always did. Valli was a gentle cow. But this day she rushed her master, struck his leg and knocked him down. The hip was broken, not a trivial matter for an 89-year-old in those days. Swami spent months in the hospital, and once released was confined to a wheelchair.

Devotees were heart-stricken by the accident, yet he remained unshaken. He ever affirmed, “Siva’s will prevails within and without–abide in His will.”

Swami was now confined to his ashram, and devotees flocked to him in even greater numbers, for he could no longer escape on long walks. He was, he quipped, “captured.” With infinite patience and love, he meted out his wisdom, guidance and grace throughout his final few years.

At 3:30 am on a Wednesday in March of 1964, Yogaswami passed quietly from this Earth at age 91. The nation stopped when the radio spread news of his Great Departure, and devotees thronged to Jaffna to bid him farewell. Though enlightened souls are often interred, it was his wish to be cremated. Today, a temple complex is being erected on the site of the hut from which he ruled Lanka for 50 years.

Natchintanai: A famous song of Satguru Yogaswami. The transliteration is:

Appanum Ammaiyum Sivame; Aria sahotararum Sivame; Opil manaiviyum Sivame; Otarum maindarum Sivame; Sepil arasarum Sivame; Devadi devarum Sivame; Ippuvi ellam Sivame; Ennai andattum Sivame.

A poetic English rendering:

Father and mother with Siva stay; Brothers and sisters light Siva’s day; Wife with no equal treads Siva’s way; Beloved children are Siva’s play; Rulers and kings under Siva’s sway; All Gods and Goddesses to Siva pray; All of the cosmos is Siva’s clay; And my Lord, You are Sivame.