With reports from ANIL MAHABIR, DEVANT MAHARAJ and PARAS RAMOUTAR, Trinidad

Each Fall the “Dipavali Village” is set up for two weeks on several acres of land on the Caroni plains in central Trinidad by the National Council for Indian Culture (NCIC). Booths are rented out to various businesses to sell crafts, food, clothes, even hardware and cars. A few religious lectures are given during the first week, but thereafter dances, fashion shows and music predominate. The Village has been popular with Trinidad’s Hindus and is the largest yearly Hindu event on the island.

The problem with Dipavali Village, complains the influential Maha Sabha, is that it has minimized religious content. “The Village has evolved into a commercial enterprise as business discovered the power of the Hindu wallet,” complains Maha Sabha executive member Devant Maharaj. “It has reduced Dipavali to a pre-Christmas shopping season.” The NCIC, they charge, is attempting to recast the festival as a “cultural observance,” a kind of Hindu carnival, not a religious event. Devant describes the NCIC as a mixed religious group comprised of Indian Hindus, Christians and Muslims, and headed by a Presbyterian, Hans Hanoomansingh.

The Maha Sabha is not the only group insisting Dipavali is a religious event. For different reasons, the Nur-E-Islam Education Committee has distributed a flyer called “Beware of Shirk [polytheism],” which advises Muslims not to participate directly in Dipavali because it is a festival in honor of Goddess Lakshmi, hence a form of “idol worship.” Hindus have taken offense at the flyer, though it is an accurate (if conservative) explanation of Islamic principles and does state, “As Muslims, we must exhibit tolerance towards other world religions.”

Like the Muslims, the “Thusians,” a local independent splinter group of the international Seventh Day Adventist denomination of Christianity, insist Dipavali is a religious festival, not a neutral cultural observance. Indeed, it is a brazen example of the worship of “graven images,” according to a eight-page fax sent to Hinduism Today by Thusian pastor Nyron Medina. He expressed this same opinion, embellished with malicious remarks about Hinduism, last March during his weekly program on a local radio station. Complaints to the station from the Maha Sabha and others got the program permanently canceled for violating the station’s prohibition on bringing another religion into disrepute or offending any community.

In defense, Medina said in his fax, “It was terribly distasteful to see the Maha Sabha and other Hindu organizations presenting to the nation that Dipavali was simply a ‘festival of lights,’ or the ‘triumph of light over darkness,’ when in fact this is not really the case at all. These Caribbean Hindus in a Christian cultural environment use these acceptable phrases to palliate the consciences of people so that it would not seem to be idolatry to participate in Dipavali. We showed that Dipavali is not really about lights, it is about the worship of the Goddess Lakshmi.”

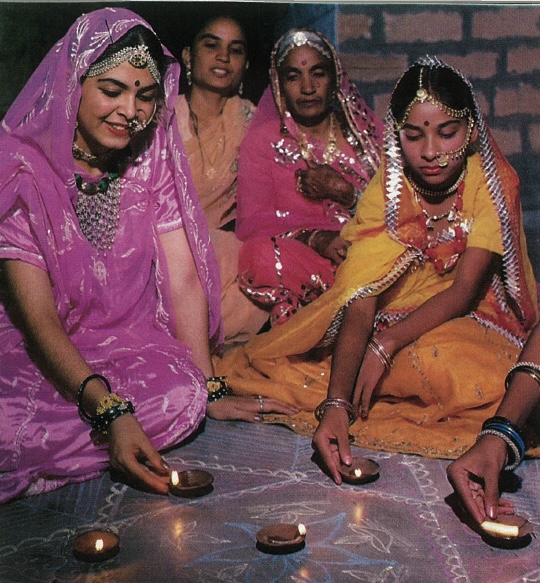

Dipavali, “Row of Lights,” is celebrated by all denominations of Hindus. It takes place in October-November the day before the new moon in Libra. There are several explanations of its origin, the most common being that it is the day Lord Rama returned to Ayodhya after spending 14 years in exile, but it is likely that the festival in honor of Lakshmi was already ancient in Rama’s time. It is the New Year’s day in the Vikram calendar–new clothes are donned, houses cleaned and businesses close out their books. In the evening thousands upon thousands of small lamps are lit and fireworks are displayed.

How to deal with festivals in a multi-religious environment has already been solved in India. There, during Dipavali, Hindus will greet their Muslim and Christian friends, and share with them the special Dipavali sweets. Similarly, on Eid-al-Fitr, the major Muslim holiday marking the end of the month-long Ramadan fast, Muslims will greet their Hindu and Christian friends and send to them the sweet vegetarian dish sewaina. Such sharing is done by Christians with their non-Christian friends at Christmas. This centuries-old solution in India doesn’t require anyone to go against his faith. But it does allow each to share the joy of their festivities with friends of other religions in an non-threatening way.