In a sequestered section of earth, protected and defined by the towering Himalayas, humankind’s relationship with Gods and demons remains vibrant and real. Tibet, known as the “Land of Snows” and the “Rooftop of the World,” has borne and continues to nurture the world’s most fantastic and other-worldy faiths. The religious landscape of Tibet is as rich and varied as the country’s terrain and as intricate as any Tibetan tangka painting. As most inhabitants still do today, early Tibetans regarded the earth, air and waters as home to a specific hierarchy of spirits, both helpful and harmful. In daily life, they sought to appease the wrathful “demons” and to enlist the beneficent deities. These practices were formalized in some cases. In others, they have remained isolated, private traditions or secret knowledge, loosely grouped together today as shamanism or animism. Modern Tibetan Buddhism shares Tibet with a religion that has uncertain links to this past. This religion is Bon. It has a limited traceable history, substantial traditional literature and detailed ritual codes. More and more, Western scholars are studying Bon, as the world slowly learns of yet another ancient way mankind seeks the Truth. The following sympathetic yet academic study is drawn from The Bon Religion of Tibet (1995, Shambhala, Boston) by Per Kvaerne, professor of the History of Religions and Tibetology at the University of Oslo, Norway.

By Per Kvaerne, Oslo

SINCE THE TENTH OR ELEVENTH CENTURY AND UNTIL THE present day there have been two organized religious traditions in Tibet: Buddhism and a faith that is referred to by its Tibetan name, Bon. An adherent of the Bon religion is called Bonpo. A Bonpo is a “believer in Bon,”and for him Bon signifies Truth, Reality or the eternal, unchanging Doctrine in which Truth and Reality are expressed. Thus, Bon has the same range of connotations for its adherents as the Tibetan word cho (chos, translating the Sanskrit term dharma) has for Buddhists. Although limited to Tibet, Bon regards itself as a universal religion in the sense that its doctrines are true and valid for all humanity. The Bonpos also believe that in former times Bon was propagated in many parts of the world (as conceived in their traditional cosmology). For this reason, it is called “Eternal Bon,” yungdrung bon.

Western scholars have adopted the Tibetan term Bon together with the corresponding adjective Bonpo to refer to ancient pre-Buddhist as well as later non-Buddhist religious beliefs and practices in Tibet. Hence, in the context of Western scholarship, Bon has no less than three significations:

1. The pre-Buddhist religion of Tibet which was gradually suppressed by Buddhism in the eighth and ninth centuries. This religion appears to have focused on the person of the king, who was regarded as sacred and possessing supernatural powers. Elaborate rituals were carried out by professional priests known as Bonpo. Their religious system was essentially different from Buddhism. The rituals performed by the ancient Bonpo priests were, above all, concerned with ensuring that the soul of a dead person was conducted safely to a postmortem land of bliss, to ensure the happiness of the deceased in the land of the dead and to obtain their beneficial influence for the welfare and fertility of the living.

2. Bon may also refer to a religion that appeared in Tibet in the tenth and eleventh centuries. This religion, which has continued as an unbroken tradition until the present day, has numerous and obvious points of similarity with Buddhism with regard to doctrine and practice. The fact that the adherents of this religion, the Bonpos–of whom there are many thousands in Tibet and in exile today–maintain that their religion is anterior to Buddhism in Tibet, and, in fact, identical with the pre-Buddhist Bon religion, has tended to be either contradicted or ignored by Western scholars. Tibetan Buddhists, however, also regard Bon as a distinct religion.

3. Bon is sometimes used to designate a vast and amorphous body of popular beliefs, including divination, the cult of local deities and conceptions of the soul. Tibetan usage does not, however, traditionally refer to such beliefs as Bon, and they do not form an essential part of Buddhism or of Bon in the sense of the word outlined under point two above. It is only since the mid-1960s that a more adequate understanding of Bon has emerged.

Subtle Distinctions: To the casual observer, Tibetans who follow the tradition of Bon and those who adhere to the Buddhist faith can hardly be distinguished. They all share a common Tibetan heritage. In particular, there is little distinction with regard to popular religious practices. Traditionally, all Tibetans assiduously follow the same methods of accumulating religious merit, with the ultimate end in view of obtaining rebirth in a future life as a human being once again or as an inhabitant of one of the many paradisiacal worlds of Tibetan (Buddhist, as well as Bonpo) cosmology. Such practices include turning prayer wheels, hand-held or set in motion by the wind or a stream; circumambulating sacred places such as monasteries or holy mountains; hoisting prayer flags; and chanting sacred formulas or engraving them on stones or cliffs. It is only when these practices are scrutinized more closely that differences appear; the ritual movement is always counter-clockwise and the sacred mantra is not the Buddhist “Om mani padme hum,” but “Om matri muye sale du.” Likewise, the innumerable deities of Tibetan religion, whether Buddhist or Bonpo, may at first appear to be indistinguishable. But again, the deities are, in fact, different (although belonging to the same range of divine categories) with regard to their names, mythological origins, characteristic colors and objects held in their hands or adorning their bodies.

Even a cursory glance at the doctrines of Bon, as expressed in their literature or explained by contemporary masters, reveals that they are in many respects identical with those found in Tibetan Buddhism. It is this fact that until recently led Western scholars to accuse the Bonpos of plagiarism. The view of the world as suffering, belief in the law of moral causality (the law of karma) and the corresponding concept of rebirth in the six states of existence, and the ideal of enlightenment and Buddhahood, are basic doctrinal elements not only of Buddhism, but also of Bon. Bonpos follow the same path of virtue and have recourse to the same meditational practices as Buddhist Tibetans.

One may well ask in what the distinction between the two religions consists. The answer, at least to this author, would seem to depend on which perspective is adopted when describing Bon. Rituals and other religious practices, as well as meditational and metaphysical traditions are, undeniably, to a large extent similar, even identical. Concepts of sacred history and sources of religious authority are, however, radically different and justify the claim of the Bonpos to constitute an entirely distinct religious community.

Hidden Holy Land: According to its own historical perspective, Bon was introduced into Tibet many centuries before Buddhism and enjoyed royal patronage until it was finally supplanted by the “false religion” (i.e. Buddhism) from India and its priests and sages expelled from Tibet by King Trisong Detsen in the eighth century. It did not, however, disappear from Tibet altogether. The tradition of Bon was preserved in certain family lineages, and after a few generations it flourished once more, although it never again enjoyed royal patronage.

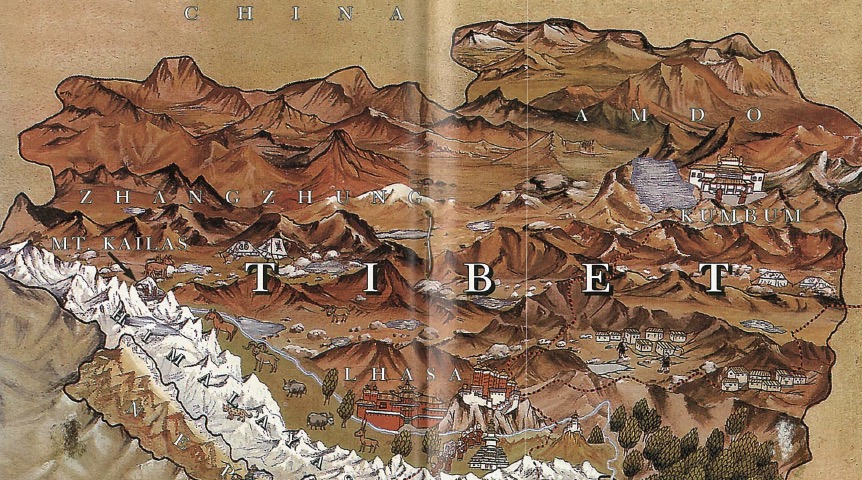

It is claimed that before reaching Tibet, Bon prospered in a land known as Zhangzhung and that this country remained the center of Bon until it was conquered by the expanding Tibetan empire in the seventh century. Zhangzhung was subsequently converted to Buddhism and assimilated into Tibetan culture, losing not only its independence but also its language and its Bonpo religious heritage in the process. There is no doubt as to the historical reality of Zhangzhung, although its exact extent and ethnic and cultural identity are far from clear. It seems, however, to have been situated in what today is, roughly speaking, western Tibet, with Mount Kailash as its center. [See map, page 28.]

The ultimate homeland of Bon is, however–so the Bonpos claim–to be found even farther to the west, beyond the borders of Zhangzhung. The Bonpos believe that Eternal Bon was first proclaimed in a land called Tazik. Although the name suggests the land of the Tajiks in Central Asia, it has so far not been possible to make a more exact identification of this holy land of Bon. Tazik is, however, not merely a geographical country like any other. In Bon tradition, it assumes the character of a “hidden,” semi-paradisiacal land which latter-day humans can only reach in visions or by supernatural means after being spiritually purified.

For the Bonpos, Tazik is the holy land of religion, being the land in which Tonpa Shenrap (the Teacher Shenrap) was born in the royal family and in due course became enthroned as king. Tonpa Shenrap is believed to be a fully enlightened being, the true Buddha (the word “Buddha” means “the Enlightened One”) of our world age. The Bonpos possess a voluminous hagiographical literature in which his exploits are extolled. One may note that his biography is not, contrary to what has sometimes been claimed by Western scholars, closely related to that of Sakyamuni. Thus, during the greater part of his career, Tonpa Shenrap was the ruler of Tazik or Wolmo Lungring and hence a layman, and it was as such that he incessantly journeyed from his capital in all directions to propagate Bon. This propagation also included the performance of innumerable rituals. These rituals, which are performed by Bonpos today, thus find their justification and legitimation in the exemplary exploits of Tonpa Shenrap. Contrary to Buddhism, where rituals generally have no direct canonical basis, in Bon, as pointed out by Philip Denwood, “We have whole developed rituals and their liturgies specified in the minutest detail in the basic canon.” It was only late in life that Tonpa Shenrap was ordained, after which he retired to a forest hermitage. It was only at this point in his career that he finally succeeded in converting his mighty opponent, the Prince of Demons.

The Bonpos have a vast literature which Western scholars are only just beginning to explore. Formerly it was taken for granted in the West that this literature was nothing but an uninspired and shameless plagiarism of Buddhist texts. The last twenty-five years have, however, seen a radical change in the view of the Bon religion. This reassessment was initiated by David L. Snellgrove, who in 1967 made the just observation regarding Bonpo literature that “by far the greater part would seem to have been absorbed through learning and then retold, and this is not just plagiarism.” Subsequently, other scholars have been able to show conclusively that in the case of several Bonpo texts which have obvious, even word-by-word Buddhist parallels, it is not, as was formerly taken for granted, the Bonpo text which reproduces a Buddhist original, but in fact the other way round: the Bonpo text has been copied by Buddhist authors. This does not mean that Bon was never at some stage powerfully influenced by Buddhism. But their relationship, it is now realized, was a complicated one of mutual influence.

Those texts which were considered by the Bonpos to be derived, ultimately, from Tonpa Shenrap himself, were collected to form a canon. This vast collection of texts (the only edition available today consists of approximately 190 volumes) constitutes the Bonpo Kanjur, forming an obvious parallel to the Tibetan Buddhist canon, likewise called Kanjur. A reasonable surmise would be that the Bonpo Kanjur was assembled by 1450. The Bonpo Kanjur, which in turn only constitutes a fraction of the total literary output of the Bonpos, covers the full range of Tibetan religious culture. As far as Western scholarship is concerned, it still remains practically unexplored.

It is difficult to assess the number of Bonpos in Tibet. Certainly, they are a significant minority. Particularly in eastern Tibet, as for example in the Sharkhog area north of Sungpan in Sichuan, whole districts are populated by Bonpos. Another important center is the region of Gyarong where several small kingdoms, fully independent of the Tibetan government in Lhasa as well as of the Chinese Emperor, provided generous patronage for local Bonpo monasteries until the greater part of the region was conquered in a series of devastating campaigns conducted by the imperial Chinese army in the eighteenth century. Scattered communities of Bonpos are also to be found in central and western Tibet. Of the ancient Zhangzhung kingdom, however, no trace remains, although Mount Kailash is an important place of pilgrimage for Bonpos as well as Buddhists. Another much-frequented place of pilgrimage, exclusively visited by Bonpos, is Mount Bonri, “Mountain of Bon,” in the southeastern district of Kongpo. In the north of Nepal there are Bonpo villages, especially in the district of Dolpo. In India, Bonpos belonging to the Tibetan exile community have established (since 1968) a large and well-organized monastery [in Dolanji, Himachal Pradesh] in which traditional scholarship, rituals and sacred dances of Bon have been preserved and are carried out with great vigor

CARDS FOR THE DEAD

Bon death rites reveal this living faith’s practice and profound belief in the role of sacred priests as guides to liberation. This account by Per Kv¾rne is from Religions of Tibet in Practice (1997, Princeton University Press), edited by Donald S. Lopez.

Tibetan death rituals, both buddhist and bonpo, basically serve to guide the consciousness of the dead person, often through a succession of initiations, out of the cycle of rebirth and toward final liberation. The consciousness of the deceased is believed to pass through several stages after death, at each of which the possibility of liberation exists.

Bonpo death rites have three parts. Immediately after death occurs, a ritual called “transference of consciousness” is performed in which a Bonpo monk attempts to transfer the consciousness of the deceased directly from the cycle of rebirth to the state of liberation.

Three days after death, a second ritual is performed in which the consciousness of the deceased is led progressively along the path to liberation. This ritual, which lasts approximately two hours, involves displaying various cards to a picture of the deceased. This takes place in the home of the deceased and is performed by a chief monk and two assistants. The corpse is present in the room but is kept behind a cloth screen. The ritual begins with the chief monk making an effigy of the deceased out of dough and offering it as a “ransom” to malevolent spirits that might interfere with the ceremony. Next, the consciousness of the deceased is summoned and asked to reside in a picture of the deceased. After cleaning the picture, the chief monk writes two series of seed syllables on it. The first series of six represent the six realms of rebirth, as a god, demigod, human, hungry ghost, animal, or hell being. The second consists of the “five heroic syllables,” which are antidotes to the rebirth in the six realms.

The next phase of the ritual involves the presentation of various gifts. This is effected through the chief monk showing the picture of the deceased a series of cards on which the gifts are depicted. Initially, all the sensory faculties (sight, hearing, taste, etc.) of the deceased are satisfied symbolically by being invoked in turn, and a series of small, painted cards depicting the object of each faculty are held up in sequence. In this way, whatever craving for material wealth and worldly power that the dead person may have experienced during his or her lifetime is appeased.

With the deceased now ritually provided with satisfaction of all material needs and ritually endowed with the mental qualities necessary for progress toward liberation, it is time for the consciousness of the deceased to be led through the stages of the path to enlightenment. The picture of the deceased is shown cards depicting four groups of deities, including the teacher, Shenrap. Finally, the deceased is shown a ritual card showing Buddha Kuntu Sangpo, the “All Good,” the essence of all the Buddhas.

The deceased, again through the use of ritual cards, is then given four initiations, after which he or she becomes an “unchanging mind hero,” the Bonpo equivalent of a bodhisattva. As such the consciousness of the deceased now passes through the thirteen stages of the path, each symbolized with a ritual card painted with a swastika. These are placed in a row on the floor, and the picture of the deceased is moved forward one card as the qualities of that stage are recited. At the end of the row is a card showing Kuntu Sangpo. Before moving to that card, the chief monk takes a lighted stick of incense and burns the six syllables symbolizing the six realms of rebirth, thus indicating freedom from all future rebirth.

Finally, to bring about the final union with Kuntu Sangpo, the chief monk places his robe over his head and enters a state of meditation in which he unites his consciousness with that of the deceased. He then unites his consciousness with Kuntu Sangpo. At this point, the deceased achieves liberation, and when the monk emerges from meditation, the picture of the deceased is burned and the ashes retained to be made into small religious figurines called tsatsa. The next morning, the third and final part of the death rite, the cremation of the corpse, takes place.