By V. G. Julie Rajan

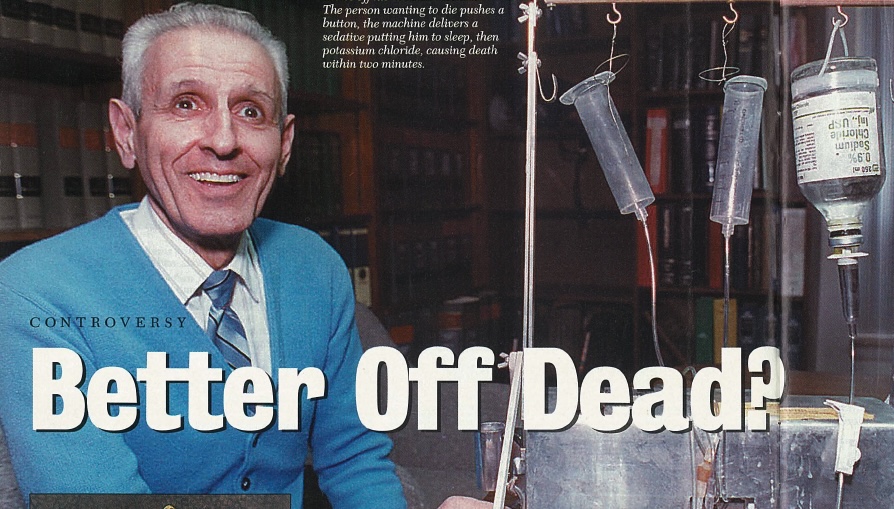

Even for a Sunday night news show, this was not your normal fare. Earlier this year “Sixty Minutes” broadcast a video tape of Jack Kevorkian–“Dr. Death”–lethally injecting Thomas Youk. Mr. Youk, age 52, suffered from the incurable Lou Gehrig’s disease, and had asked to die. But Youk’s death was different from that of the previous 130 people Kevorkian says he has helped to die, beginning with Janet Adkins in 1990. Mrs. Adkins, an Oregon resident, age 54, suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, pushed the button on Kevorkian’s “suicide machine” that automatically injected her with potassium chloride. With Youk, Kevorkian did the injecting himself. He was arrested, charged, convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to ten to 25 years. He had taken the movement toward “assisted suicide” one step too far. [See www.freep.com/suicide/index.htm on Kevorkian’s history.]

Kevorkian’s decade-long campaign was intended to bring to the forefront the question of the care of the terminally ill. He is an advocate of legal, doctor-assisted euthanasia–a Greek word meaning “good death” and usually juxtaposed to the prospect of a long, lingering death. The issue is a result of modern medical technology which can prolong the life of people who just a few decades ago would have died quickly as a result of their disease or injury.

The term euthanasia is popularly applied to several types of circumstances that are not the same in terms of morals, ethics or religion. At one extreme is Kevorkian’s treatment of Youk. Youk wanted to die, Kevorkian killed him by lethal injection. When a doctor deliberately and knowingly increases a patient’s morphine drip (intended to relieve pain) to the point of a lethal dose, he also has killed his patient. Removing a comatose patient from nourishment without his express prior authorization, causing his death by starvation, is illegal. However, not treating a patient by, for example, not performing cardio-pulmonary resuscitation when the patient has a heart attack, can be viewed as “letting nature take its course.” This is an important distinction from the Hindu point of view. Finally, we have the circumstance of suicide proper, where the person himself performs an action that ends his life. Suicide can be quick, as with a lethal dose of pills, or slow, as with fasting to death.

An informative statistic: in the US, 2.3 million people died in 1998. Thirty-three percent succumbed quickly to disease or died by accident, requiring no “end-of life” care. Twenty-three percent were admitted to hospice programs that provided a comfortable setting and eased the pain of dying, but made no attempt to extend life. The remaining 45 percent died in hospitals. The hospice movement itself is a response to the complex issue of dying in a medically advanced society. It has developed from almost nothing to its present scale in just twenty years, according to Stephen Connor of the National Hospice Organization in Virginia.

Hindus, with their long tradition of respect for the elderly, may feel exempt from the problem of care of the dying, because this duty has always been the solemn responsibility of the family. But times are changing, quickly in the urban centers, slowly in the villages. Keralites were shocked earlier this year by a petition from four elderly men to legalize doctor-assisted euthanasia in India. According to an Associated Press report early in 1999, “Experts say the elderly are increasingly neglected and isolated, particularly in Kerala, because the life expectancy is 70 years, far above India’s average of 59.” The result of the increased longevity is economic pressure on the younger generation, who must support aged parents longer and through more debilitating illnesses. Attitudes have also changed. “Old people are discarded by their descendants. Their property is grabbed by their relatives. I see this all around me,” said 69-year-old Mukundan Pillai to AP. He is a retired school teacher and one of those who filed the petition.

Manu Kothari, an anatomist at the Seth G.S. Medical College in Parel, Mumbai, has studied the issue of euthanasia in India and elsewhere. He’s upbeat about the situation in India, “I’ve been a doctor for 40 years, and I am amazed at the care given to the elderly. India doesn’t ignore the old. I have the feeling that in America the elderly person suffers great emotional deprivation, because no one is caring for him. They consider suicide not because of disease but because of the absence of human touch.” Kothari is against legal euthanasia. “It is not a weapon worth giving into the hands of mankind,” he said.

For the time being, Hindu attitudes toward the elderly will probably keep the issue of euthanasia at bay. “In India, age is equated with wisdom, and here [in the US] age is equated with senility,” said Sheela Reddy, a Hindu PhD student studying psychology at Rutgers University. “There age is respected, versus here where with age your respect level goes down. You’re put in an old-age home. As you die, you are really alone, whereas in India your children try to make you feel comfortable.”

Kothari makes a useful distinction between death and disease. We may fear disease and the associated pain, he said, but we should not fear death. “Nature is compassionate and merciful when it unmakes us. Death is a very well designed process, always very well timed.” Hinduism Today publisher Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, in his new book, Merging with Siva, writes, “Pain is not part of the process of death. That is the process of life, which results in death. Death itself is blissful. You don’t need any counseling. You intuitively know what’s going to happen. Death is like a meditation, a samadhi. That’s why it is called maha (great) samadhi. A Hindu is prepared from childhood for that mahasamadhi.”

The kind of suicide advocated by Kevorkian is, from the Hindu point of view, not a “good death” at all. Swami Brahmavidyananda of the Institute of Holistic Yoga in Miami, Florida, stated that the soul who has committed suicide escapes nothing. Following suicide, the soul wanders on the astral plane, a kind of temporary damnation. Then it is reincarnated in another physical body wherein the same suffering will occur again because the same karma is still present. “Man, even if he leaves the physical body, will suffer in another body. It’s not finished. That is the real Vedic philosophy,” he concluded. Swami Rameswarananda of the International Yoga and Daily Life Center in Alexandria, Virginia, concurred: “Liberation, moksha, is the only way out of the cycle. Unless one attains wisdom, there is always life and death.”

Whereas Kevorkian’s approach to euthanasia is bold, more quiet acts of euthanasia may be occurring in hospitals in the US. One Hindu doctor, who asked his name not be used, said, “In medical terms, euthanasia is a mercy killing. In many hospitals, nobody ever does it, it is against the law. But if the patient is in the terminal stage of illness, we may advise the family that the patient will be like a vegetable, not conscious and unable to recognize his relatives. We will tell the family that we don’t have to be very aggressive in resuscitating efforts when the patient has a crisis. If the family says, ‘Please do whatever you can,’ then we do whatever we can until the very end.” According to one doctor, medical technology is so advanced that nearly anyone in any stage of illness can be kept alive on machines and can only really die when unplugged.

Swami Rameswarananda argues, “Once you make euthanasia an institution, then it will get out of control, because of the ego involved in it. The person cannot understand all the consequences. They cannot bear the pain now, they think, but they will be born again, and maybe in greater pain. It’s very short-sighted.”

Swami Brahmavidyananda says that the negative and helpless state of mind in which one chooses euthanasia will impact the process of reincarnation. “The last thought, whichever you have when you die, upon that depends your next incarnation,” he warns.

Dr. Devananda Tandavan, medical columnist for Hinduism Today, offered, “Euthanasia goes against my principles as a physician, which are stated in the Hippocratic Oath, more than 3,000 years old.” That oath, sworn originally to “Apollo, Aesculapius and all the Gods and Goddesses,” states in part, “I will follow that system which I consider for the benefit of my patients, and abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous. I will give no deadly medicine to any one if asked, nor suggest any such counsel; and in like manner I will not give to a woman a means to produce abortion. With purity and holiness I will pass my life and practice my art.” That such prohibitions were formulated in ancient times shows euthanasia, “doctor-assisted suicide” and abortion are not new issues.

Now retired for ten years after a 44-year practice in radiology, Dr. Tandavan said in his entire career he never heard of patients asking to commit suicide. He attributes the change to recent concepts of “rights.” “When I was in school, we didn’t even know we had those rights, and we didn’t care. People now think of their rights because of their own selfish desire. If they’re suffering from cancer, they want to have control of their lives, since it is, supposedly, one of our rights. But if they wanted to exercise their rights, they should have done it a long time ago, changed their diets and not gotten cancer.”

Dr. Tandavan believes that a terminally-ill patient’s family members “may want them out of the way because it’s costing too much to keep them in the hospital.” If a person were to ask Tandavan about euthanasia, he said, “I would tell them about how the soul has to have a body, and if the body is suddenly taken away, the soul is lost–temporarily, of course–and doesn’t know where to go. The soul is much more important than the body. Medicine cannot predict the intricacies of life on earth. To end a life that is suffering does not allow for the very, very, very occasional miracle that does happen. I have never been able to predict how long someone has to live from their ailments. All we doctors do is play averages.”

A common, but little-known problem, in hospitals is lack of respect for the dying. Harried doctors and nurses simply don’t have time, nor necessarily the training, to comfort those for whom medicine offers no further benefit. One California man, dying of emphysema, was so put off by the demeaning way he was treated by the hospital personnel that he called his family, and demanded they take him home. Once home, he turned off his oxygen tank and died the same night. One solution to this is a hospice, where knowledgeable and sympathetic caretakers can facilitate a dignified end to life. Families can visit as much as they want at the hospice, sit with the patient, read scriptures, etc., all to assist the transition.

In some hospitals, families are not adequately consulted about the patient. One person in New Jersey told us they discovered their father, who was in a teaching hospital, was being used for experimental treatments, without their permission. Further, the staff allowed the family visits for only 15 minutes a day, despite the fact there was no hope of recovery. When the hospital finally took him off life support, they didn’t even notify the family of their intent, just phoned to tell them he died. Families should not hesitate to aggressively involve themselves in the care of their relatives, demanding–if necessary–to be informed of the treatments, and insisting on lengthy visiting hours, or even staying with the patient.

The practicalities of death: According to Indian philosophy and metaphysics, death is a natural and wonderful event, not to be feared. Death also has its own natural timing. We should, therefore, not fight too hard nor run too far when we sense Lord Yama’s imminent arrival. “The problem comes when doctors bring the dying back,” writes Subramuniyaswami. “To make heroic medical attempts that interfere with the process of the patient’s departure is a grave responsibility, similar to not letting a traveler board a plane flight he has a reservation for, to keep him stranded in the airport with a profusion of tears and useless conversation.” In America, one must make a legal declaration, in advance of illness, instructing doctors not to make heroic efforts, put one on life support, etc. Without this “Living Will,” every effort will be made to keep the patient alive, as doctors have no other option under the law.

It is not acceptable from the Hindu point of view for the doctor to kill the patient, even at the patient’s request. Such intervention causes separation of the soul at an unnatural time, with karmic consequences both for the doctor and the patient. The issue of the comatose patient is more controversial, but from the Hindu point of view, as long as there is life in the body, which means the process of decay has not set in, the soul is still connected. Death has not occurred, even if the person is so-called “brain dead.” It is better not to get into this situation, by not going on life support in the first place, or by taking oneself off it when still sufficiently conscious to order it done. But once on it, and once the patient is not conscious, if death occurs because the life support is shut off, that is again an unnatural intervention. There is a great deal of difference between a patient who yanks out his feeding tube and says, “Let me die,” and a doctor who does the same and says, “Now die.”

Self-willed death: Hinduism does provide a means to end one’s own life when faced with incurable illness and great pain and debilitation. That is fasting to death, prayopavesa, under strict community guidelines. Gandhi’s associate, Vinod Bhave, died in this manner, as did recently Swami Nirmalananda of Kerala. It is generally thought of as a practice of yogis, but is acceptable for all persons. Prayopavesa is a rare option, one which the family and community must support–to be sure this is the desire of the person involved and not a result of untoward pressures.

It is not necessarily an easy experience, for the person or for the relatives. Devi–not her real name–recently helped her 90-year-old mother-in-law, living in Northern California, fast to death. Devi explained, “She announced she would fast rather than undergo any more medical treatment, and began to go through her personal phone book and call whomever she wanted to and say good-bye. The doctors accepted her decision, and we got some help from a hospice worker. But it was more difficult than any of us expected. At first, when she stopped the medication, she actually got better. But she was in a lot of pain. She died in three weeks. Her doctor signed her death certificate, and the local coroner, who recorded the cause of death as ‘self-starvation,’ asked us a lot of questions, but said we faced no legal trouble. I’m an initiated Buddhist, and at her request we read scriptures to her, especially the Tibetan Book of the Dead, and chanted ‘Aum.’ My advice to anyone involved in this form of dying is to have a legal statement of intent drawn up by the person. It is necessary, too, that someone be available who has experience with the stages of death, which, like childbirth, is a less frightening experience if one knows what to expect.”

It is neither necessary nor desirable to artificially prolong the life of the body. Working from this one unassailable conclusion, how to deal with the terminally ill becomes more clear. Certainly disease and injury can be aggressively treated. But when recovery is not going to happen, and the quality of life has deteriorated, then the patient has every right to refuse more medical treatment, to be taken off life support systems, to go home or to a hospice and die with dignity. For to miss the natural timing of death can have serious consequences for the karmic patterns of future births. The Hindu also has the right to refuse aggressive treatment in the first place, and to accept the natural timing of his passing.

RITES OF TRANSITION

HINDU DEATH RITUALS REFLECT DEEP REVERENCE FOR THE “GREAT DEPARTURE”

Hindu death rituals, first set forth in the ancient Vedas, remain largely the same across all the lands Hindus inhabit. It is a family rite, assisted by special priests, and can be described in ten parts:

1. The Approach of Death

Traditionally, a Hindu dies at home, attended by his loved ones who keep vigil, singing hymns, praying and reading scripture. A lamp is lit near his head. He is urged to concentrate on God, and prepare for the greatest spiritual experience of his life, his soul’s departure from the body.

2. The Moment of Death

If the dying person is unconscious at departure, a family member chants a mantra softly in the right ear. Holy ash or sandal paste is applied to the forehead, Vedic verses are chanted, and a few drops of milk, Ganga or other holy water are trickled into the mouth. The lamp is kept lit near the head and incense burned. After death, a cloth is tied under the chin and over the top of the head. The thumbs are tied together, as are the big toes. Religious pictures are turned to the wall. Relatives are beckoned to bid farewell and sing sacred songs at the side of the body.

3. The Homa Fire Ritual

The special funeral priest is called. In a shelter built by the family at the home, a fire ritual (homa) is performed to bless nine brass kumbhas (water pots) and one clay pot. Lacking the shelter, an appropriate fire is made in the home. The chief mourner–for the father, the eldest son; the youngest son for the mother–leads the rites

4. Preparing the Body

The chief mourner now performs arati, passing an oil lamp over the remains, then offers flowers. The body is privately bathed with the water from the nine pots, dressed, placed on a palanquin, then taken to the shelter. The children, holding lighted sticks, encircle the body, singing hymns. Women then walk around the body and offer puffed rice to nourish the deceased for the journey ahead. A widow will place her tali (wedding pendant) around her husband’s neck.

5. Cremation

Only men go to the cremation site, led by the chief mourner. Two pots are carried: the clay kumbha and another containing burning embers from the homa. The body is carried three times counterclockwise around the pyre, then placed upon it. Offerings are made. With the clay pot on his left shoulder, the chief mourner circles the pyre while holding a fire brand behind his back. At each turn around the pyre, a relative knocks a hole in the pot with a knife, letting water out, signifying life’s leaving its vessel. At the end of three turns, the chief mourner drops the pot. Then, without turning to face the body, he lights the pyre and leaves the cremation grounds.

6. Return Home

Returning home, all bathe and share in cleaning the house. A lamp and water pot are set where the body lay in state. The shrine room is closed, and white cloth draped over all icons. During these days of ritual impurity, commonly one month, family and close relatives do not visit others’ homes, though neighbors and relatives may bring daily meals. Neither do they attend festivals and temples, visit swamis, nor take part in marriage arrangements. Scriptures admonish against excessive lamentation, as prolonged grieving can hold the departed soul in earthly consciousness, inhibiting full transition to the heaven worlds. In Hindu Bali, it is considered shameful to cry for the dead.

7. Bone-Gathering Ceremony

About twelve hours after cremation, family men return to collect the remains. Water is sprinkled on the ash; the remains are collected on a large tray. At crematoriums the family can arrange to personally gather the remains. Ashes are carried or sent to India for deposition in the Ganges or placed in an auspicious river or the ocean, along with garlands and flowers.

8. First Memorial

On the 3rd, 5th, 7th or 9th day, relatives gather for a meal of the deceased’s favorite foods. A portion is offered before his photo and later ceremonially left at an abandoned place, along with lit camphor. Customs for this period vary. Some offer pinda (rice balls) daily for nine days. Others combine all these offerings with the subsequent sapindikarana rituals for a few days or one day of ceremonies.

9. 31st-Day Memorial

On the 31st day, a memorial service is held. In some traditions it is a repetition of the funeral rites. A priest purifies the home and performs the ritual offering of rice balls. Afterwards the pindas are fed to the crows, to a cow or thrown in a river for the fish. Once the sapindikarana is completed, the ritual impurity ends.

10. One-Year Memorial

At the yearly anniversary of the death, a priest conducts the shraddha rites in the home, offering pinda to the ancestors according to custom.

My first symptoms of ALS occurred in 2014, but was diagnosed in 2016. I had severe symptoms ranging from shortness of breath, balance problems, couldn’t walk without a walker or a power chair, i had difficulty swallowing and fatigue. I was given medications which helped but only for a short burst of time, then I decided to try alternative measures and began on ALS Formula treatment from Tree of Life Health clinic. It has made a tremendous difference for me (Visit w w w. healthcareherbalcentre .com I had improved walking balance, increased appetite, muscle strength, improved eyesight and others. ]