Interview by Amritha Sivanand

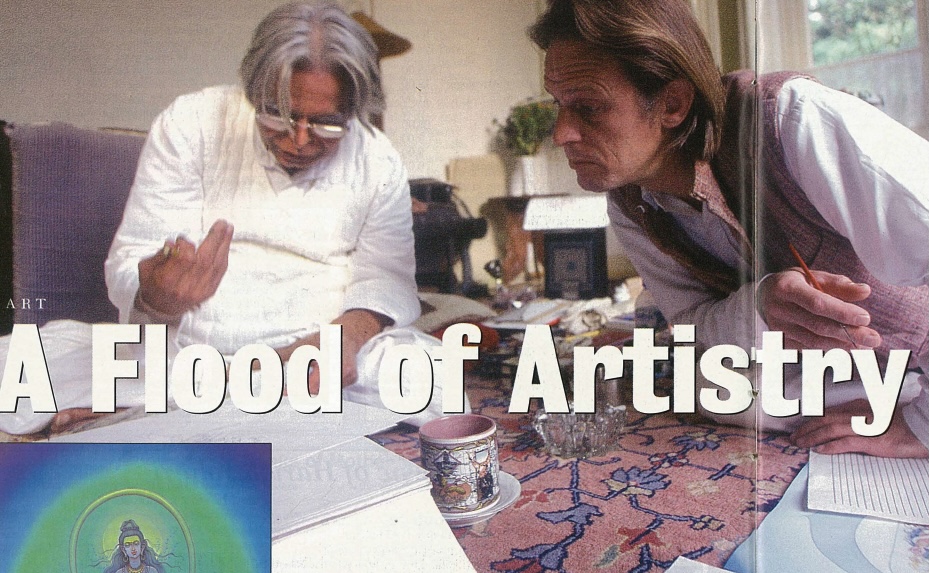

To get away from the things of the world which take energy and bother,” Harish Johari told Hinduism Today correspondent Amritha Sivanand, “the best way is to think of God, paint God, talk about God, write about God and that way spend all your energy thinking about the One who appears as many and is yet One.” So began her interview with one of India’s most versatile men–a gifted artist and able composer, a popular expounder in both lectures and books on the healing arts, astrology, yoga, tantra, numerology, gemstones, even massage and cooking. Johari, age 64, was in a jocular mood for the interview. “It was a joy to watch him,” reported Amritha from Holland, “His entire personality is one of creativity.” Johari’s most recent creation is Birth of the Ganga, a stunning collection of 45 paintings done with Pieter Weltevrede (his Dutch student of 20 years, and in whose home the work was done) and collaborators.

“Every year from the age of two,” recalls Harish, “I went to Haridwar and came to love Ganga. She has the power to heal, to purify and to energize. I thought it would be very good to do Her story, because I love Ganga and you like to paint whatever you love.” Ganga’s biography is well known, and Harish follows the traditional stories from the Skanda Purana and other sources. He recounts how Ganga originated in heaven from the energy of Lord Vishnu, then descends to Earth as a result of the penance of King Bhagirath to liberate his ancestors from the netherworld. Each painting depicts one of the scenes, such as when Lord Siva catches Ganga in His hair to break Her torrential fall to Earth, or how She is led out of the Himalayas and across the plains of India by the king, finally reaching the ocean at the Bay of Bengal.

The book is important for its sophisticated art–the result of decades of development by Johari. “I did not copy any style,” he explained. “I liked the art work which was done in Ajanta Caves [200 to 600 ce, Buddhist, located in west-central India]. They drew very beautifully, nice eyes, nose, formation of the body. I also saw at Elephanta Caves [near Mumbai, 600 ce] that the proportions used in the sculptures were beautiful. And at Khajuraho [900 ce, central India], I saw the way in which they expressed stories and the various hand gestures. From this I developed a unique style which actually existed thousands of years ago, but in the form of sculptures, not painting.” Specifically, Johari explains, “Our work is mostly line work, because we believe that it is very important to be clear in what you do, which can only be seen through your lines.”

The technique combines that delicate dark line art with pastel watercolor shades and an overall color cast created in the final washing stages. The silk paintings are mostly done in browns, greens or blues and, though obviously “Indian,” are very unlike typical poster art. The best are the masterfully composed kinetic scenes, such as of Ganga being led through the plains [above], as well as the divine depictions, such as Ganga emerging from Brahma’s chalice [at left]. These are capable of eliciting a primordial devotional response of Godliness, even if a person had no knowledge of the subject matter.

Johari’s main collaborator and student, Dutch-born Pieter Weltevrede, 43, began his study of art twenty years ago. He worked nonstop for one year to create the paintings in Birth of the Ganga. “Although I helped with the compositions, color selecting and the finishing of the paintings,” Johari writes in an afterword to the book, “it is Pieter who deserves the admiration for creating such a beautifully illustrated story.” Pieter was born a Roman Catholic but, he said, “I consider myself more a Hindu because they are more open.” Married with three children, Pieter became a vegetarian 25 years ago and started the practice of yoga, but painting is his main form of religious expression. “I find that painting gives peace and makes one calm. It helps concentration and is a preparation for meditation,” he said. Fortunately for Hinduism, Pieter has pursued this form of art in lieu of more lucrative commercial art–an option only made possible by support from the Dutch government. It is enough to allow him to paint all the time, and he says he is weltevrede–his family name–which means “well-satisfied.”

Johari took to the canvas as a child. Every year, for example, on Janmashtami, his family would paint the story of Krishna’s life. “The whole family worked together,” he recalled. “My mother made the borders, my father the landscapes, my uncle the stones, my other uncle Krishna sitting on those stones, my sister, my brother, everybody contributed to it. We’d paint Krishna doing so many things–playing with a cow, lifting an elephant, running, jumping, standing. It was done all in one day, and from it I learned storytelling through art.” The specific technique of wash painting used in Birth of the Ganga Johari learned from Shri Chandra Bal, who in turn learned it from Bhawani Prasad Mittal who studied art at Shanti Niketan, founded by Rabindranath Tagore. In this method, both watercolor and tempera are used, and the paintings are rinsed with water several different times to remove excess color and allow additional colors to be applied without interference [see photos page 23]. Shri Chandra Bal has also directly instructed Pieter in this method and helped with the Ganga paintings.

If Johari’s family life and education were unusual, his entry into adult life was decidedly extraordinary. As a young man he worked as a factory manager. However, upon getting married he asked his new wife if she was “prepared to starve.” He explained to her that he wanted to pursue a career in art, and that almost certainly meant they would be poor for a long period of time, but in the end both happy and rich. The alternative for her, he said, might likely be a miserable husband unhappy with years in a boring job. She agreed, and Johari quit his promising job the next day–to the astonishment and utter dismay of his mother. He then took up art projects not for money, but for payment in kind–clothes, rice, spices, etc.–and that way managed to avoid even having to shop. “We had no money to spend, but we had food to eat, clothes to wear and everything I needed was there.”

Johari likens learning art to studying language in order to write a novel or to write poems. One must learn the necessary grammar, vocabulary and writing techniques. The aspiring artist, he advises, “should likewise learn to sketch, to draw, to paint, to use depth, highlights and middle tones; to know which colors go together and which don’t, to understand the difference between harmony, contrast and balance. If they know these, they have the freedom to compose whatever they want. Then you must be a great observer, and know what things look like. Good art needs no captions to explain itself.”

Johari had a bigger vision than just success in art. He is blessed with the ability to sleep just three hours a night–2 am to 5 am. As a result, he says, “You find it very difficult not to learn and not to absorb, because otherwise what will you do? I didn’t want to go to a club or spend my time gossiping. Instead I would sit with a vaidya, a doctor, or a musician, a painter, an astrologer.” His sleeplessness made him an expert in a number of esoteric fields, and produced over a dozen books–all wonderfully illustrated, and several among the best available on their subject.

“I am a follower of Sanatana Dharma, the ancient religion, also known as Hinduism,” Johari explains about his religious beliefs. “In the ancient religion, they worshiped one God with so many forms. They knew that behind everything there is one energy that is working, the Shakti or mother principle. The science that especially works with this Shakti is called tantra. But it is not the tantra that is known in the West. When I came here for the first time, people said, ‘Oh, you do tantra, then can you teach me some of the sexual things?’ I said that my tantra is not that tantra. My tantra is the tantra of devotion, of concentration, of worship. It is a method that makes it possible for people to get what they want through meditation and concentration.”

Johari is an advocate of using both sides of the brain–the right side of intuition, imagination and art; the left side of analysis, language, reason and computation. “I think God has given you two sides, and you are supposed to use both. Have faith, but don’t trust blindly. Doubt everything, but doubt the doubt. Some people doubt God, and believe their doubt as dogmatically as people who believe in God. The best thing is to know and understand and fall in love with God.”

“If asked,” Johari went on, “I will say that as I am called, I’m a Hindu. But I think of myself as a person who sees the Divine in everything and can accept every holy book as a holy book, every Deity as a Deity, and every person as God incarnated in a particular form. I think Hinduism provides lots of inspiration to live, and it tells you that whatever you get from the world is all divine. The light of the sun, the ocean, the mountains, the river, the trees are not just nature without intelligence, without consciousness, and you have the right to do whatever you want to do with them because you are the king and they are just your subordinates. That is something which is very wrong. Hinduism teaches you to see God in everything. That is the greatest lesson that it gives. It inspires you to adopt practices which make you more civilized and friendly, more lovable and enjoyable, more inspired, a good person and a good citizen of the world.”

BIRTH OF THE GANGA AND OTHER BOOKS BY HARISH JOHARI ARE AVAILABLE FROM INNER TRADITIONS, ONE PARK STREET, ROCHESTER, VERMONT 05767 USA. PHONE: 802-767-3174; FAX: 802-767-3726, EMAIL: WWW.GOTOIT.COM. SEE AD ON PAGE 19 OF HARD COPY