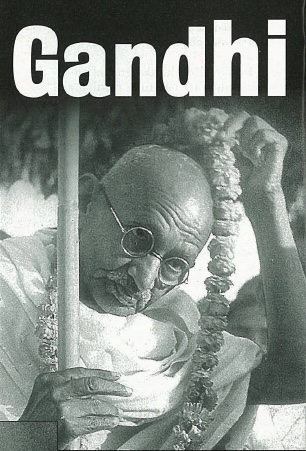

Gandhi was a brilliant, complex and selfless man, understood in different ways by different people. No one will ever deny his profound effect upon society in and beyond India, an impact as complex, perhaps, as the man himself. Exactly what did Gandhi leave us? Author Mark Shepard spent a substantial portion of his life in devoted study of the life and work of this larger-than-life legend. He wrote the book Gandhi Today and numerous articles about it. Below, we share Mark’s insights into Gandhi and his thinking, especially with regard to nonviolence.

It is surprising how many people have the idea that nonviolent action is passive. There is nothing passive about Gandhian action. Gandhi himself helped create this misunderstanding by referring to his method at first as “passive resistance,” because it was in some ways similar to techniques bearing that label. But he soon changed his mind and rejected the term.

Gandhi’s nonviolent action was not an evasive strategy, nor a defensive one. Gandhi was always on the offensive. He believed in confronting his opponents aggressively, in such a way that they could not avoid dealing with him. But wasn’t Gandhi’s nonviolence designed to avoid violence? Yes and no. Gandhi steadfastly avoided violence toward his opponents. He did not avoid violence toward himself or his followers. Gandhi said that the nonviolent activist, like any soldier, had to be ready to die for the cause. And, in fact, during India’s struggle for independence, hundreds of nonviolent Indians were killed by the British. The difference was that the nonviolent activist, while willing to die, was never willing to kill.

Three Ways to Respond

Gandhi pointed out three possible responses to oppression and injustice. One he described as the coward’s way: to accept the wrong or run away from it. The second option was to stand and fight by force of arms. Gandhi said this was better than running away. The third way, he said, was best of all three, but required the most courage: to stand and fight solely by nonviolent means.

Who Started It?

One of the biggest myths about nonviolent action is the idea that Gandhi invented it. While he did raise nonviolent action to a level never before achieved, it was not at all his creation. Gene Sharp of Harvard University, in his book Gandhi as a Political Strategist, shows that Gandhi and his Indian colleagues in South Africa were well aware, in 1906, of mass nonviolent actions in India, China, Russia and among blacks in South Africa itself. In another of his books, The Politics of Nonviolent Action, Sharp cites over 200 cases of mass nonviolent struggle throughout history. And he believes many more will be found if historians take the trouble to look.

Nonviolence in the US

Curiously, some of the best earlier examples come from the United States in the years leading up to the American Revolution. To oppose British rule, the colonists used many tactics amazingly like Gandhi’s. And, according to Sharp, they used these techniques with more skill and sophistication than anyone else before Gandhi’s time.

For instance, to resist the British Stamp Act, the colonists widely refused to pay for the official stamp required to appear on publications and legal documents a case of civil disobedience and tax refusal, both used later by Gandhi. Boycotts of British imports were organized to protest the Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts and the so-called Intolerable Acts. The campaign against the latter was organized by the First Continental Congress, which was really a nonviolent action organization. Almost two centuries later, a boycott of British imports played a pivotal role in Gandhi’s own struggle against colonial rule.

The colonists used another strategy later adopted by Gandhi setting up parallel institutions to take over functions of government and had far greater success with it than Gandhi ever did. In fact, according to Sharp, colonial organizations had largely taken over control from the British in most of the colonies before a shot was fired.

Journalists and Historians

To know about current and past events, we depend a great deal on journalists and historians. One thing that journalists and historians understand is military power. They know what results from many people being shot or imprisoned. It’s obvious when such power is being used, and a journalist or historian can feel professionally safe in describing and analyzing it.

Most of them, however, do not deal so well with subtle, nonviolent forms of power. They don’t understand how such power operates. The fact is, even in revolutions that are primarily violent, the successful ones usually include nonviolent civilian actions not so different from the ones Gandhi used. And, nearly every time, these actions are curiously down-played or ignored by most journalists and historians. As Indira Gandhi put it, “The meek may one day inherit the earth, but not the headlines.”

Truth-Force and Civil Disobedience

Gandhi called his overall method of nonviolent action satyagraha. This translates roughly as “truth-force.” A fuller rendering, though, would be “the force that is generated through adherence to truth.” Nowadays, it’s usually called nonviolence. But, for Gandhi, nonviolence was the word for a different, broader concept namely, “a way of life based on love and compassion.” In Gandhi’s terminology, satyagraha was an outgrowth of nonviolence.

Gandhi practiced two types of satyagraha in his mass campaigns. The first was civil disobedience, which entailed breaking a law and courting arrest. He used “civil” here not just in its meaning of “relating to citizenship and government” but also in its meaning of “civilized” or “polite.” And that’s exactly what Gandhi strove for. But to Gandhi the core of civil disobedience was going to prison. Breaking the law was mostly just a way to get there, and getting there was a way to provoke support.

Gandhi wanted to say, “I care so deeply about this matter that I’m willing to take on the legal penalties, to sit in this prison cell, to sacrifice my freedom, in order to show you how deeply I care. Because, when you see the depth of my concern, and how ‘civil’ I am in going about this, you’re bound to change your mind about me, to abandon your rigid, unjust position, and to let me help you see the truth of my cause.”

In other words, Gandhi’s method aimed to win not by overwhelming, but by converting his opponent or, as the Gandhians say, by bringing about a “change of heart.”

The belief that civil disobedience succeeded by converting the opponent was perhaps a misconception, one held by Gandhi himself. To this day it is shared by most of his admirers. But as far as I can tell, no civil disobedience campaign of Gandhi’s ever succeeded chiefly through a change of heart in his opponents. However, this does not mean civil disobedience didn’t work. It did.

Here is what I believe happened when Gandhi and his followers committed civil disobedience: They broke a law politely. A public leader had them arrested and put in prison. Gandhi and his followers cheerfully accept it all. Members of the public are impressed by the protest. Public sympathy is aroused for the protesters and their cause. Members of the public put pressure on public leaders to negotiate with Gandhi. As cycles of civil disobedience recur, public pressure grows stronger. Finally, a public leader gives in to pressure from his constituency and negotiates with Gandhi. That’s the general outline.

Notice that there is a “change of heart,” but it’s more in the public than in the opponent. And notice, too, that there’s an element of coercion, though it’s indirect, coming from the public, rather than directly from Gandhi’s camp. Gandhi’s most decisive influence on his opponents was more indirect than direct.

Gandhi set out a number of rules for the practice of civil disobedience. These rules often baffle his critics, and often even his admirers set them aside as nonessential. One such rule was that only specific, unjust laws were to be broken. Civil disobedience didn’t mean flouting all law. In fact, Gandhi said that only people with a high regard for the law were qualified for civil disobedience. Only action by such people would convey the depth of their concern and win respect. No one thinks much of it when the law is broken by those who care nothing for law anyway.

Gandhi also ruled out direct coercion, such as trying to physically block someone. Hostile language was banned. Destroying property was forbidden. Not even secrecy was allowed. All these were ruled out because any of them would undercut the empathy and trust Gandhi was trying to build.

Noncooperation

A second form of mass satyagraha was noncooperation. It took such forms as strikes, economic boycotts and tax refusals. Of course, noncooperation and civil disobedience overlapped. Noncooperation was to be carried out in a “civil” manner. Here, too, Gandhi’s followers had to face beating, imprisonment, confiscation of their property and it was hoped that this willing suffering would cause a “change of heart.” But noncooperation also had a dynamic of its own, based not on appeals, but on the power of the people themselves. Gandhi saw that the power of any tyrant depends entirely on people being willing to comply with unjust rules. The tyrant may get people to obey by threatening to throw them in prison, or by holding guns to their heads. But the power still resides in the obedience, not in the prison.

Gandhi said, “I believe that no government can exist for a single moment without the cooperation of the people, willing or forced, and, if people suddenly withdraw their cooperation in every detail, the government will come to a standstill.” That was Gandhi’s concept of power.

Does Nonviolence Really Work?

Some of Gandhi’s critics say: Maybe nonviolent action does work but it’s just too slow. People are suffering injustice, slavery, starvation and murder. How can you ask them to be patient and work nonviolently? There are so many variables that comparisons between one situation and another are difficult, but certainly, we cannot say that violence is always quick. If we look at the Chinese Revolution, for instance, we find that Mao Tse-Tung and his Communist forces were engaged in combat over a period of 22 years. Vietnam was embattled for an even longer period: 35 years. These are not swift victories. We can also dispel the notion that nonviolent action has to be slow. The nonviolent overthrow of Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines took only three years.

Nonviolent action requires more patience, because the action is less thrilling. And violence, even when it succeeds, has major negative side-effects side-effects that nonviolent action mostly avoids. First, a violent struggle will tend to bring about much more destruction of life, property and environment. Other consequences of violence come into view once the struggle comes to an end. For instance, violence generally leaves the two sides as long-standing enemies. Maybe the most amazing thing about Gandhi’s nonviolent revolution is not that the British left but that they left as friends, and that Britain and India became partners in the British Commonwealth. Gandhi noted that violent revolutions almost always end in repressive dictatorships. And, of course, bitter enemies within a country continually need to be put down and kept down. Gandhi hoped that a nonviolent revolution, led by civilians, would avoid all this.

India today is not a paradise. It is afflicted by widespread injustice, civil violence and authoritarian trends. Still, it is one of a few Third World countries where democracy has survived continuously and dynamically.

Gandhi never meant to defeat anyone. He saw satyagraha as an instrument of unity. It was a way to remove injustice and restore social harmony to the benefit of both sides. Gandhi’s satyagraha was for his opponent’s sake as well. When satyagraha worked, both sides won. This is the essential difference between Gandhi’s nonviolence and that of most others.

Mark Shepardis the author of Gandhi Today as well as numerous articles which have appeared in 21 magazines and books around the world. He lives in Arcata, California.