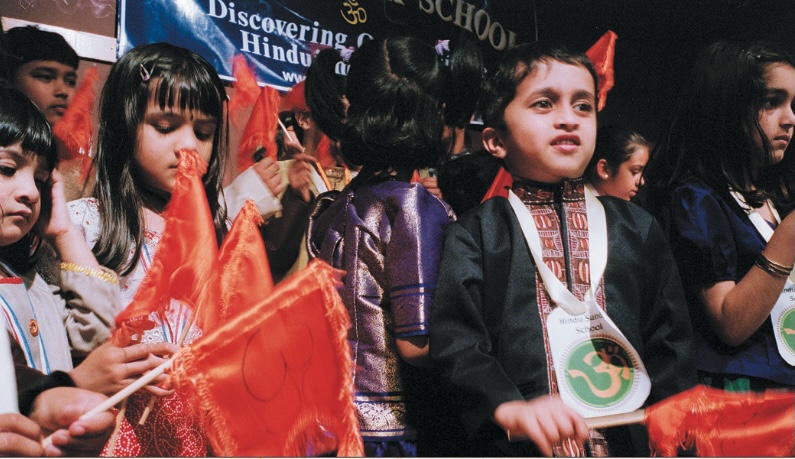

Just as at many other temples in the US, Hindu parents in Middletown, Connecticut, looked around one day in the Sri Satyanarayana Temple and asked, “Where are the kids?” They saw that their American-born children had little knowledge of Hinduism, and even less interest in. They realized that if they didn’t engage them in their rich religious and cultural heritage, it might soon be lost. So, a team came together and formed the “Hindu Sunday School “. It has been a grand success, with more than fifty children ranging from ages six to sixteen attending consistently for two and a half years.

Sunday school is an American institution. Long ago, immigrants of Western religions faced the challenge of passing on their heritage to generation after generation, and they figured out a system which is now the primary mode of religious instruction for millions of American children. The whole country is scheduled around attending church on Sunday. While the parents worship the chapel, the kids attend “Sunday school.” The Hindu parent-teachers who launched this program decided to take advantage of this established church model, and it worked. Hindu kids in the Hartford, Connecticut, area actually like it, and they keep coming back. They no longer have to wonder what they should do while their school friends are in Sunday school on Sunday mornings.

The program is working out so well that it drew the attention of The Hartford Courant, a newspaper based in the state capital, which ran a prominent story about the Hindu Sunday School in its June 16, 2003, edition. As Courant staff writer Frances Taylor put it, “The curriculum is a systematic way of transferring a complex blend of beliefs and practices to the next generation.”

After looking at the programs offered by Hindu gurukulams and balavihars in the area, Divya Jyothi Difazio, one of the founding teachers at the school, was so inspired one night that she wrote down the entire twelve-month curriculum. She explained that they base their 90-minute class format on the Sai Baba teaching model: “The children all get together for a half-hour of Aum chanting, bhajana singing and japa, and then break into groups based on the curriculum that has been adjusted for each age group.”

Kindergartners and first-graders learn simple songs and Sanskrit chants, with emphasis on pronunciation and learning the meanings in English. They also play games and share art and craft projects. Older kids go more in depth, learning about puja and homa, prayer, meditation and chanting, yoga, history, Vedic philosophy and Hindu traditions.

Teenagers are called “leaders in training.” Divya Jyothi explained, “The leaders in training program is for young people who are more firmly established in their faith and heritage and ready to develop leadership skills, primarily to become teachers for the younger children. There are nine kids in this program now. They work on developing leadership skills and on meeting goals through such projects as putting together bhajana books and resources for the younger kids’ classes, conducting seva projects, gathering inspirational quotes for study circles, writing plays and individual study projects like the eight limbs of yoga and others. Then they work on how they can take that information and gear it down for the younger kids.”

Occasionally the school brings in swamis, guest storytellers and performers, such as a recent Bharata Natyam dancer, to expose the children to traditional Hindu culture. However, the main thrust is to educate them about their religion. Beena Pandit, the school’s current coordinator, declared, “We must enlighten kids about Hinduism and give them answers instead of leaving them feeling disarmed and not knowing what to say, feeling they don’t fit in. We have to take every chance we get to contribute to their awareness of Hinduism.”

Teacher Asha Shipman, 32, a second-generation American Hindu, is an anthropology student at the University of Connecticut and a former high school teacher. She shared, “The kids love being here. They are so happy. The enthusiasm of these children is so delightful. As they learn their slokas and learn about the Gods and Goddesses, the modes of philosophy, do their coloring, they are so engrossed in what they’re doing. I didn’t have this as a Hindu growing up in the US.”

Keeping the interest of the younger children isn’t a problem. The key is keeping everything loose and flexible. Beena Pandit advised potential start-up Hindu Sunday schools, “Don’t make it too rigid. These children are bombarded with tons of homework and challenges in their secular schooling. Don’t make Sunday school a place they don’t want to come because they have to do this and that and they’re being corrected a lot. Put interesting things in front of them, more hands-on activities that appeal to them.”

According to Asha Shipman, the real challenge lies in keeping the interest of the high school kids. She confided, “It’s hard to find materials that are appropriate for them. Most things are usually too simple or too complex. One of the hardest things about teaching people is getting to them at the right level.”

There has been widespread support for the Hindu Sunday School amongst the Sri Satyanarayana Temple’s administration and devotees. Enthusiastic parents signed up about 100 kids for the school’s first semester. Subsequent semesters have seen sign-ups of about 50-60 children consistently, possibly due to the new $25 enrollment fee. There are now waiting lists for the younger kids’ groups, thanks to the coordinators’ wise choice to limit each class group to fifteen children. The number of children the school can enroll hinges on a limited number of qualified teachers, so there is new emphasis being placed on the leaders in training program.

Maintaining the interest of the parents is also a weight on the balance of enrollment and attendance. It takes as much commitment from the parents as from the teachers. Madhu Reddy, the school’s main visionary, lamented, “Sometimes kids want to come, but their parents don’t bring them. It has to be done with wholehearted commitment on everyone’s part. It has to be consistent.”

This Hindu Sunday School has been so successful that it could serve as a model for other temples. When asked what his advice would be to temple groups wanting to start a Sunday school, Reddy offered, “Put together a team. That team is very important. Every member must want to promote Hindu heritage and pass it on to the next generation.” As for how to keep it all going once it’s started: “Think through the long-term plan. Otherwise, it will die out after a while. You need backup so people don’t burn out. It requires a lot of responsibility on the part of the teachers, parents and the temple.”

Perhaps the most important step the Hindu Sunday School teachers keep taking toward making their school a success is to listen to the children and pay attention to their needs. Beena Pandit summed it up, “It has to be for the children, teaching with them in mind. You can’t adhere strictly to your own agenda of what you think they should be doing and learning. Kids are turned off by teachers who have an inflexible agenda. They learn in different ways. Those who came from other countries to the US and established temples here can’t expect their US-born kids to walk in their footsteps. These are American kids, not Indian kids, and they’re going to do things in their own way. Find out what that way is.”

Visit http://www.hinduschools.org [http://www.hinduschools.org] for more information about the hindu sunday school