BY OLIVIA WU

The chanting of mantras to invoke and give thanks to God before partaking of a meal is an ancient Hindu tradition, one that has perhaps been unfortunately forgotten by many Hindus who have left the traditional village for the cosmopolitan city. Here are excerpts from a charming article in the San Francisco Chronicle reaffirming the value of “saying grace, ” the wonderful, universal tradition of mealtime blessing that takes place wherever people eat, together or alone.

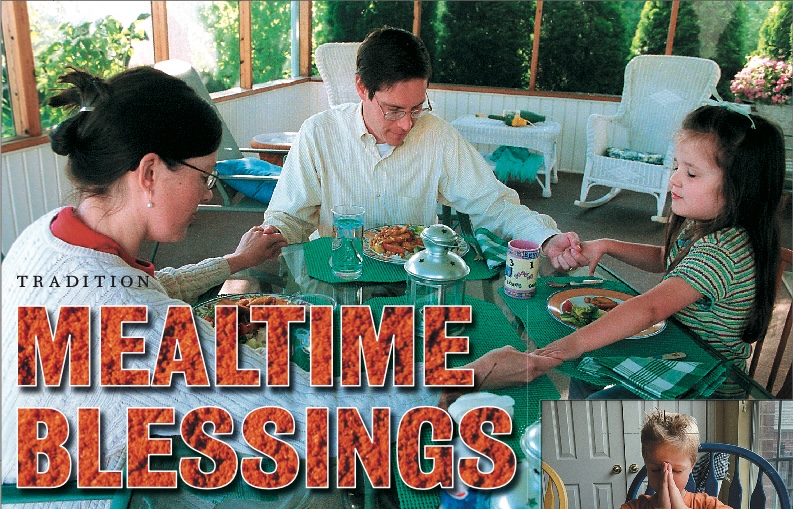

Wiggling and whispering builds as the three children and eight adults assemble around the dinner table. In the final flurry of spoons, asparagus and water, the father asks for silence. Then Chris Colson, 10, eyes bright, sings in a clear boy-soprano, “For all things good, for friends and food, we give Thee thanks, O Lord.” His two foster sisters, 6 and 4, chirp in. In the controlled chaos of Sunday night dinner at the Colson home in San Francisco, the melody etches a searing stillness. A focus snaps into place, and the crazy crush of this three-generation, blended family becomes whole.

Every day, all over the San Francisco Bay Area, saying grace whether to honor a God, celebrate the food or bring a family together lifts the curtain on mealtime. Despite fast food, the fast lane and the rapid erosion of the traditions of dinner time, millions of Americans cleave to this ritual.

In the gym of the Third Baptist Church in San Francisco’s Western Addition, the thumping of basketballs ceases and 40 African American children straggle toward folding tables to hold hands. A moment of stillness, and then, from the lips of a 17-year-old, the blessing.

In the East Bay, a robed monk lifts seven grains of rice above his head, re-enacting a centuries-old daily ritual before a handful of lay members of the Berkeley Buddhist Monastery. They chant a prayer and segue into the weekly Saturday community vegetarian meal, eating in focused silence.

Lynnie, a single, 33-year-old San Francisco woman who is a member of Overeaters Anonymous, sits before her plate and bows her head. She says thanks for the food, and thanks that “this plateful be enough.”

The act of slowing down begins with the blessing of a meal. In a 1998 Gallup poll, 64 percent of Americans said they express gratitude by saying grace at meals; in 63 percent of families with children under 18, someone says it aloud. “Mealtime prayer is a pretty enduring feature in many people’s lives, ” says Gustav Niebuhr, a fellow at the Center for the Study of Religion in Princeton, N.J. The numbers, which have stayed constant since the 1960s, suggest that families lean on the pillars of tradition, but individuals are also joining the ranks in creative, ecumenical ways.

“It’s not just that the food is blessed but that the process of eating is itself a renewal, ” says Mark Jurgensmeyer, professor of sociology and religious studies and director of Global and International Studies at UC Santa Barbara. “The idea of ingestion is almost universal within religious traditions as a sacramental act.”

Even for individuals who are not traditionally religious, “There is this little pause at the beginning of a meal, ” Jurgensmeyer says. “You don’t eat before everybody is served, and often there is a toast, a salute. And that will be a kind of grace a moment of reflection and appreciation. And that’s all grace is.”

Graces: Prayers for Everyday Meals and Special Occasions, by June Cotner, (HarperSanFrancisco, 1994), a collection from many faiths, is in its 31st printing and has sold more than 200,000 copies. Cotner believes her book’s popularity shows a hunger for spirituality. A reverent pause before eating in an edgy world affirms family and teaches reverence, Cotner says. She estimates that only 60 percent of those who buy her book are churchgoers. The rest turn the food blessings into opportunities for polyglot fusions, and inspirational, in-the-moment expressions of thanks.

Immigrant families often rely on mealtime rituals to stay connected to their roots and to recall what’s important. Luis Trucios of Redwood City, originally from Peru, is raising two children, ages 3 and 5. Prayer was core in his childhood, and prayer is how he keeps tradition, especially at dinner, “because that’s when we’re together. It leads to meaningful conversation, ” he says. The message of thanks for the source of food breeds connections beyond the table. Trucios and his wife complete the connections by shopping and cooking with their kids. “They understand the whole circle of food, ” he says.

For British-born John Farrington of South San Francisco, a single father, a simple “little moment of stillness ” in the blessing with his 7-year-old son, Gabriel, “brings history into my son’s life. It is a conduit to talk about my history in England.” Sensitive to hunger issues, Gabriel recently surprised his father by setting aside half of the waffle he ordered at a restaurant to give to the homeless. “Through giving and prayers, he’s not thinking of food for himself, ” says Farrington. He knows we live in a world (of hunger), not just in America.”

Giulio Sorro, 27, of San Francisco is Italian-Filipino, from a lapsed Catholic family. Living as a Bridges Fellowship volunteer among the Luya tribe in Kenya transformed his relation to food. He saw hunger, the always imminent threat of drought, and heard his hosts’ heartfelt prayers, which fused Christianity and native religion. “They thanked God and the Earth for the food. They thanked the food, ” says Sorro.

Says Rev. Heng Sure, director of the Berkeley Buddhist Monastery, “We make our most intimate connection every day through the mouth.” The practice of offering food affirms that “I do participate and I am of this fabric, ” so that the act of eating turns into an act of compassion. A traditional Buddhist prayer says, “In this food I see clearly the presence of the entire universe supporting my existence.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “For each new morning with its light. For rest and shelter of the night. For health and food, for love and friends. For everything thy goodness sends.”

Republished with permission of the San Francisco Chronicle from their June 4, 2003 edition; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, inc.

A TRADITIONAL PRAYER OF GRATITUDE TO THE SOURCE OF SUSTENANCE

A BHOJANA MANTRA CHANTED BY HINDUS BEFORE MEALS

Aum annapurne sadapurne Shankaraprana vallabhe;

Jnanavairagya siddhyartham bhiksham dehai cha Parvati.

Mata cha Parvati Devi pita Devo Maheshvara

Bandavah Shiva bhaktascha svadeso bhuvanatrayam.

Aum purnamadah purnamidam purnatpurnam udachyate,

Purnasya purnamadaya purname vava shishyate.

Aum shanti shanti shanti.

Aum Shivarpanamastu.

Aum, beloved Shakti of Siva, fullness everlasting and fully manifest as this food; O, Mother of the universe, nourish us with this gift of food so that we may attain knowledge, dispassion and spiritual perfection. Goddess Parvati is my mother. God Maheshvara is my father. All devotees of Siva are my family. All three worlds are my home. Aum, That is Fullness. Creation is fullness. From Divine Fullness flows this world’s fullness. This fullness issues from that Fullness, yet that Fullness remains full. Aum, peace, peace, peace. Aum, this I offer unto Siva.

LINES 1-4 ARE FROM SRI ADI SANKARA’S ANNAPURNASHTAKAM. LINES 5-6 ARE THE ISA UPANISHAD INVOCATION. LINES 7-8 ARE A TRADITIONAL SAIVITE CLOSING.