BY MADHU KISHWAR

Many people in India find it difficult to justify or reconcile themselves to the fact that in a culture which worships Saraswati as the Goddess of Learning, so many girls are deprived of even primary education; in a culture which worships Lakshmi as the Goddess of Wealth, so many modern-day Lakshmis live a slavish life of economic dependence; in a culture where male Gods have had to appeal for perfection to the feminine Shakti, women among many communities are not allowed to venture out of their domestic confines without male protection. This bewilderment and guilt has compelled numerous people to pick up cudgels on behalf of women, throwing up important social movements. It is noteworthy that a majority of women’s rights struggles and movements in modern India have been often initiated, led and sustained by men.

In the nineteenth century, considered by many as a period of severe erosion of women’s rights in India, Vidyasagar in Bengal, Ranade and Phule in Maharashtra, Veerasalingam in Andhra, Lala Devraj in Punjab and a host of others committed their entire lives to the cause of women. In the writings of these social reformers, cutting across regional and caste boundaries, woman as the wronged matri shakti, is a recurring metaphor. A good part of their efforts went into convincing other men that Indian society could not make progress as long as their partners stayed oppressed, that the country’s freedom could not be won as long as women were denied their rightful due in the family and in society. To women, their message was that they should recognise their own feminine shakti and become modern-day Durgas without, of course, losing Sita’s nurturing qualities.

Sita is considered a very negative role model, the hallmark of wifely slavery for most of those who consider themselves progressives and feminists. Her suffering is seen as a product of masochism, lack of selfhood and supine surrender to patriarchy. Many Indian “modernists ” see Sita as an adversary whose influence among people is to be countered. The association of the feminine with nurturing mother figures is seen as a patriarchal conspiracy to put women in restrictive and self-effacing roles.

Needless to say, this projection is altogether contrary to the popular perception of Sita. The Ramayana tells the story of a whole spectrum of voluntary sacrifices and hardships endured by most of the main characters in their resolve to adhere to their dharmic codes. However, it is Sita’s sacrifices, and the raw deal meted out to her, that loom much larger in the Indian consciousness than the hardships undergone by any of the other characters in the epic. Sita emerges as the final moral touchstone of the story. Her pain and sorrow hang heavily on the collective consciousness of the Indian people like that of no other character, divine or mortal.

Sita short-changed:

The popular obsession with Sita’s predicament is rooted in the three episodes after her liberation from Ravana’s captivity: her agnipariksha (ordeal by fire), her later banishment by Rama and, in the end, Rama’s demand for a second fire-ordeal, which she rejects through an appeal to her mother, Prithvi (Goddess Earth), to receive her back into Her womb. These episodes, as depicted in the Valmiki Ramayana, have disturbed devotees and nondevotees alike throughout the centuries. Rama’s treatment of Sita, in the latter parts of the Ramayana, remains immensely controversial and has provoked innumerable attempts by successive generations to critique and rework their relationship. From Kalidasa and Bhavabhuti to Kamban, Tulsidas and contemporary writers such as Bharat Bhushan Agarwal and Maithili Sharan Gupt, authors have challenged Rama’s behavior towards Sita or have attempted to reform Rama to make him prove himself a more worthy husband for her.

Who is to blame?

This obsession with reforming Rama has to do with the popular perception of Sita as perfection incarnate, so much so that even Maryada Purushottam Rama, the Divinely Perfect Rama, does not measure up to her. Sita is seen as flawless, despite the fact that she brings about trouble for everyone by crossing the magic circle of protection around her forest hut. In this projection, people have voluntarily glossed over those few occasions when Sita behaves unreasonably as in her castigation of Lakshmana, accusing him of lustful intentions towards her at the time he refuses to follow her dictates and go to help Rama in the forest.

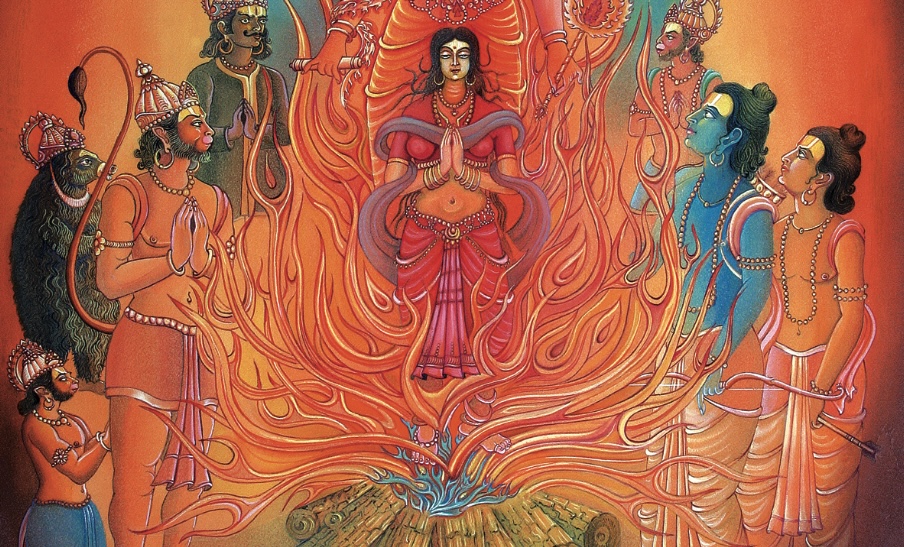

Whereas feminists interpret Sita’s offer to undergo agnipariksha as an act of surrender to the whims of an unreasonable husband, in popular perception it is seen as an act of defiance that challenges her husband’s aspersions. Sita emerges as a woman that even Agni, the Fire God–who has the power to destroy everything He touches–does not dare harm.

My assessment is that while no one in India feels offended if Rama is asked to improve, reform and change some of his anti-women notions, people unencumbered by “isms ” are not enthusiastic about Sita being subjected to “improvements ” which make her behave altogether out of character. Politically inspired attempts to make Sita lose the very qualities that make her Sita are resented or simply dismissed by those who have some roots in their culture and tradition.

Sita as ally:

If we want people to gracefully yield space for our newly acquired ideologies, we have to learn to be tolerant and respectful of those they already hold. There is no need to treat our traditional Gods and Goddesses as adversaries, especially considering that they are willing to come a long way to support our causes. At the heart of this controversy between these two opposing approaches to social and religious reform is the key question: How do we relate to our cultural heritage and define our relationship to our own people and the values they cherish?

Do we disown tradition and position ourselves outside it, or do we accept it as our own, in the way we accept our gene stock? Owning up to our traditions does not imply subscribing to every one of their pathological norms and endorsing harmful practices. It simply means learning to distinguish between inherently unjust practices and those that one doesn’t like because one has adopted a different value framework.

Social reformers can be effective only when people see them as caring insiders who have stood by them in their various trials and tribulations. But if we descend as attacking outsiders, focusing solely on practices we disapprove of, we will not make much of a dent. Only by creating a shared sense of right and wrong with the people whose lives we wish to change for the better can we create a new social consensus for a more just and humane society within our respective communities.

Mahatma Gandhi was among the most creative reformers who instinctively understood the creative potential of many of our traditions and values. For example, he used the Sita symbol to advocate the idea of women’s strength, autonomy and ability to protect themselves rather than depend on men for safety. His Sita was like a “lioness in spirit ” before which Ravana became “as helpless as a goat.” For the protection of her virtues even in Ravana’s custody, she did not “need the assistance of Rama.” Her own purity was her sole shield.

Gandhi’s Sita became a symbol of swadeshi or the decolonization of the Indian economy. He asked the women of India to follow her example by wearing Indian homespun and boycotting foreign fineries because Gandhi’s Sita would have never worn imported fabric. Gandhi wanted to create a whole army of new Sitas who were not brought up to think that a woman “was well only with her husband or on the funeral pyre.” He wanted them to stop aspiring to be mere wives and instead become leaders of men, teaching them the message of peace and social harmony.

Even those who are put off by Gandhi’s use of Hindu religious symbols for political mobilization and who have problems with many of his views on women and sexuality do not deny that, more than any other modern leader, he helped create a favorable atmosphere for women’s large scale and respectful entry into public life. Gandhi’s moral backing legitimized women’s right to hold political office without having to wage long-drawn battles, like the Suffragists in the West had to do to. His Sitas were encouraged to break the shackles of domesticity, to come out of purdah, to lead political movements and teach the art of peace to this warring world.

Joshi’s movement: In recent years, the Shetkari Sangathana leader Sharad Joshi also used the Sita symbol to drive home a radical message of gender justice among the farmers of Maharashtra. It was in 1986 that I was first invited to come and work out a program of action for the Shetkari Sangathana’s women’s front, the Shetkari Mahila Aghadi. An important outcome of my inputs and interactions with the Mahila Aghadi was the Lakshmi Mukti Karyakram. That is, the program for Liberating Lakshmis–the Goddesses of wealth. Sita is believed to be an incarnation of Lakshmi. An ordinary wife is also referred to as a Lakshmi of the household–a grihalakshmi. The Lakshmi Mukti Karyakram revolved around the idea that the peasantry could not get a fair deal for itself and would remain exploited by urban interests as long as the curse of Mother Sita stayed on them, that is, as long as they kept their wives or grihalakshmis enslaved by keeping them economically dependent and powerless in the family. The Sangathana announced in 1989 that any village in which a hundred or more families transferred, of their own accord, a piece of land to the wife’s name would be honored as a Lakshmi Mukti Gaon, a village which had liberated its hitherto enslaved Lakshmis.

This campaign became the real turning point in my understanding of the powerful emotional hold of certain traditional symbols on the psyches of people of all ages and varied communities in India. During the campaign tours, while I would use images and examples from contemporary life, Sharad Joshi’s speeches revolved around the Sita story, which seems to have played a crucial role in striking a deep emotional chord among the Sangathana followers. I quote from his very evocative speech which first establishes a link between the daily privations, drudgery and acts of loyalty of the wives of ordinary, poor farmers and the privations suffered by Sita in Valmiki Ramayana:

“During our struggle for remunerative prices I taught you to calculate the cost of production of farm produce and asked you to get into the habit of noting down each and every item of agricultural work and the cost involved. I would now suggest another exercise: On an off day, just sit down in a quiet corner of your house and start noting down on a long sheet of paper the various tasks your Lakshmi performs from as early as five in the morning to late at night: feeding the cattle, followed by all the chores required for the upkeep of the house and its surroundings, cooking, fetching water, and the care of children. All these by themselves represent a full day’s work. But she goes on non-stop.

“After completing housework, she goes to the fields and, at the end of a back-breaking day of work, on her way back home, she tries to scrounge around and collect anything that can be used as firewood for the evening meal. Then she follows with a second round of tasks–cooking the evening meal, looking after little children, feeding the animals and tending to the needs of other family members including the old and sick. From the time she wakes up to feed the cattle to the time she lays down to sleep, she has probably put in no less than 15 hours of work. How do you calculate in rupee terms the love, care and affection that she puts into all these tasks? How do you put a money value on the services of a person who saves the honor of the family by going and stealthily borrowing milk or sugar from the neighbors so she can provide tea for your guests who come at an unexpected hour at a time when the house does not have those provisions? Let us put the value of all these acts of loyalty and love at zero. But shouldn’t she get at least as much money as a person working for the Employment Guarantee Scheme gets for simply moving earth from one place to another?

“Let us figure out the value of her labor on the basis of a minimum wage of 12 rupees per day [then us$1]. She works 365 days a year. Let us say she has been married to you for 20 years. Given that she has worked 365 days a year for 20 years, the amount comes to more than 160,000 rupees [$12,700]. She has never tried to demand this amount you owe her, nor sent a notice with a jeep load of people to come, seize and take away your household utensils as the bank officials do when you owe much smaller amounts as agricultural loans to government banks. On the contrary, to save you from other creditors, remember how often she even sold off the little bit of jewellery she was wearing? If we calculate the total, along with the interest, it comes to a minimum of 400,000 rupees [$31,700]. What have you given her in return? Two saris for a whole year and that, too, forgotten if there is a drought. No guarantee of even adequate food. If there is not enough food in the house, the husband’s share is not reduced. And a mother will hardly snatch food away from her own children’s mouths. She makes do with whatever is left over–a half or a quarter chapati and fills the rest of her stomach by drinking water. This has been her fate so far.”

Having thus established the credentials of their wives as no less self-effacing than Sita Mata herself, Joshi goes on to show them that they are emulating a very negative role model and being as ungrateful and uncaring as was Rama:

“That this situation is not new is certain. But how and when did it start? Prabhu Ramchandra is considered a purushottam, the ideal human. But think of how he treated Sita Mata, who joyfully embraced exile in the forest for 14 years to be with him. As soon as Rama was appointed as king, he decided to cast her off. It is not necessary for us to get into a debate on whether it was right or not for Rama to give up Sita. But was it not necessary for him to at least take the trouble of explaining to Sita why, as a king, he was compelled to abandon her? He could have assured her that she need not lack anything after his parting company with her, that she could continue living respectably in Ayodhya. Better still, Rama should have told his subjects: ‘If she is not good enough for you as a queen, I will go along with her.’ After all that is what she had done when Rama was banished by Kaikeyi who had told Sita she could continue living in the palace. But Sita had said, ‘Jithe Rama, tithe Sita’; [ “Wherever Ram goes, there goes Sita “]. Even if Rama was not ready to leave his kingship for her, surely there were less cruel ways to deal with the situation. Sita was pregnant at that time. If Rama had provided her a small straw hut till the time of her delivery, he would not have lost any of his greatness by doing so.”

Joshi then links the story to an architectural relic which stands as testimony to the injustice done to Sita in popular imagination: “There is a Sita temple at Raveri village of Maharashtra. The villagers in that area tell you that Sita Mata delivered her two sons on that very spot. She was in such a destitute condition that she went begging for a handful of grains. The people of village Raveri spurned her and refused to give her any. Sita Mata cursed them in her grief. Such was the power of that curse that not a grain of wheat would grow in that village for centuries (until the arrival of the hybrid variety), even though the neighboring villages produced plentiful harvests of wheat. In other words, the poverty of Indian farmers will not go away unless they get rid of the curse of Mother Sita by atoning for the misdeed of Rama. They can do so by repaying their debt to their own Lakshmis and free themselves of her curses. After all the husband of a slave cannot be a free man.”

Sharad Joshi would conclude his speech by saying that the purpose of the Lakshmi Mukti campaign was to see that no modern-day Sita would ever have to suffer the fate of Rama’s Sita because she had nothing to call her own, no house or property of her own. By transferring land to their wives, they were paying off “a long overdue debt ” to Mother Sita: “Through this gesture you, my farmer brothers, will be vanquishing that monster of male tyranny which even Prabhu Ram could not vanquish though he slayed a greater warrior like Ravana with ease.”

This is indeed a hard-hitting critique of Bhagwan Rama, and yet no one seemed to mind because Joshi was drawing upon popular sentiment on this issue even while putting it far more strongly. In village after village, I saw men reduced to tears as Sharad Joshi retold the story of Sita, adapting it movingly to the context of the campaign. Within a couple of years, hundreds of villages had already been honored as Lakshmi Mukti villages and hundreds more had volunteered to carry out Lakshmi Mukti. Most of the villages that carried out Lakshmi Mukti celebrated it as though it were a big festival. We would find the entire village decorated with buntings, balloons and rangoli (colored floor designs). We would be received with women performing aratis (worship with oil lamps) while men danced to the beat of celebratory drums. Men seemed even more elated than women–some of the men I interviewed described the whole campaign as a mahayagna, a great religious sacrifice.

For as long as it lasted, this unique campaign was able to draw deep emotional response because Mother Sita has the power to guilt-trip the most hard-hearted Hindu men to respond to her plea for justice. Needless to say, this campaign for women’s economic rights could take off in rural Maharashtra in large part due to Joshi’s charisma and credibility as a leader. However, as the Sangathana gravitated more and more towards electoral politics, it lost a good deal of its power to evoke similar enthusiasm for such nonpartisan, moral causes. Is it because, while people in India have let Lord Rama be dragged into the murkiness of electoral politics, they do not want Mother Sita to be used for such narrow purposes?

Madhu Kishwar, New Delhi, is editor of Manushi, India’s leading magazine on human issues, especially women’s rights. This essay is a revised version of excerpts from two essays in Manushi–A Journal about Women and Society published from Delhi since 1978: “Of Humans and Divines, Female Moral Exemplars in the Hindu Tradition, ” issue 136 of 2003, and “Yes to Sita, No to Ram: The Continuing Hold of Sita on Popular Imagination, ” issue 98 of 1997. Both these issues and subscriptions to Manushi can be ordered from Manushi, C1/3 Sangam Estate, 1 Underhill Road, Civil Lines, Delhi 110054 India. E-mail Manushi@nda.vsnl.net.in

The journey of goddess sita is very sad and inspiring at the same time, she explained us the true meaning of love and devotion towards her husband, where she has to go through sp many ups and down in her life, although she was a princess and married to the king of Ayodhya, but unfortuntely she has to live a simple life like others, her journey always teaches us one thing i.e to never give up on anything and always fight for the truth. so thank u so much for this beautiful blog, i appreciate your effects for creating this blog, Also i m here to promote a brand called poojapaath which is famous for its handmade incense sticks with soothing fragrance so if you looking for an incense sticks online at an affordable price then do visit poojapaath now:-

https://www.poojapaath.com