BY LOIS ELFMAN

Colleges and universities across North America have offered courses on Hinduism and South Asian studies for decades, but for the most part few people of Indian origin have availed themselves of these classes. Over the past 10 to 15 years, however, professors of such courses have noticed that the number of enrollees of Indian heritage has increased significantly. With this shift come new classroom dynamics. Classes now comprise a diverse range of students in terms of familiarity with the course material. Perhaps more significantly, students with Hindu backgrounds are tackling a very personal area in an academic setting. One impact is for classes to reawaken Hindu students to their own religion. Another is that students may strongly challenge stereotypes, misconceptions and biased research that are taught as fact in classes, leading even their teachers to reevaluate their presentations.

“Occasionally students speak about how something contradicts their personal knowledge, experience or belief, ” says Vasudha Narayanan, professor of religion at the University of Florida, former president of the American Academy of Religion and founder of the Center for the Study of Hindu Traditions (CHiTra) at the University of Florida. “I say, ‘Yes, but taken from a historical stand or from a linguistic stand, these are the answers the scholars give. Whether one accepts it or not is up to you, but we discuss these in classes.’ We lay out these areas as problematic and keep going.”

Professor Narayanan, who has taught at the University since 1982, readily acknowledges the changing demographics in her classes. She says the presence of Hindus has helped non-Hindus experience the complexity and diversity of the practice of Hinduism first hand.

“When I tell about a story or a ritual or when a Hindu student does, someone usually will interject, ‘I heard a slightly different version of it,’ or ‘We do it a different way,’ or ‘We don’t celebrate this ritual.’ This tells the rest of the class that Hinduism is not something everyone celebrates the same way. Students from the Caribbean have a very important voice in talking about this. By getting the students involved and giving them a voice on such issues, allowing them to challenge or to question the textbooks and to augment the textbooks with their own experiences, we can keep them engaged.”

Part of her approach comes from her own experiences as a student. While studying at Harvard in the mid-1970s, Narayanan took a course titled “New Testament 101 ” taught by a Catholic priest who was also a respected scholar. She was deeply impressed by his ability to objectively discuss the New Testament within a historical context. “I’ve tried in my approaches to have that sense of academic integrity as well as sensitivity to the students’ own faith and what they grew up with, ” she says. “Quite often it works, but sometimes it doesn’t.”

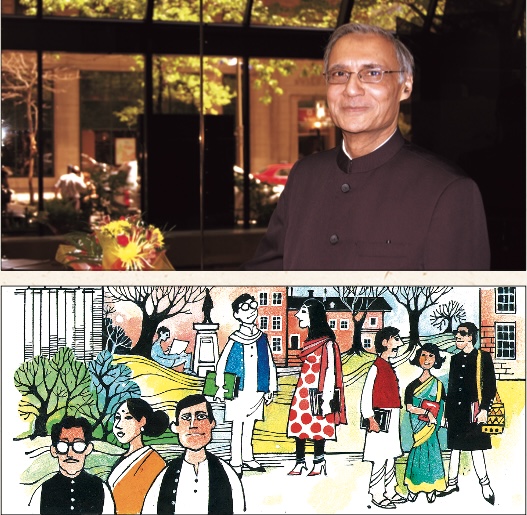

Arvind Sharma, Birks professor of comparative religion at McGill University in Montreal and an internationally renowned author and scholar, says he largely utilizes the phenomenological approach, particularly in introductory courses. This means teaching religious traditions from the perspective of the insider or believer.

“Your basic goal is to make the religious tradition intelligible–to the insider and to the outsider, ” he explains. “Given the nature of the method and the nature of the goal, the scope for conflict between what one has learned at home, for instance, and what one is being taught is narrowed by this approach. Moreover, when there are differences, and these do arise, the discrepancy is clearly addressed. It is pointed out that this is what people believe, but this is what historians see. Because the spirit is to make the tradition intelligible, the difference does not remain as sharp as you might imagine.”

There are certainly trying moments when Hindu students grapple with academic analysis. Sharma recalls one time while teaching Advaita Vedanta when he described something as pre-scientific. “Some of the Indian students in the class looked at me somewhat darkly, ” he says. “I don’t think they liked the expression pre-scientific. I was only using an expression that is used in our textbooks. This was a very interesting experience for me. I realized that while I was treating the subject at that moment as a mere academic exercise in explaining to them what the views of Advaita Vedanta are in epistemology–the investigation of what distinguishes justified belief from opinion–the fact that I referred to these views as pre-scientific did offend them as people of faith. I then became more cautious in the words I use, because it is not my intention to convey an impression other than utmost respect for what I am teaching.”

Although Helen Asquine Fazio, Ph.D., did not teach Hindu studies during her six years as a lecturer at Rutgers University in New Jersey, the classes she taught, such as Introduction to Literatures of India and World Mythology, did touch on similar subjects. She said some of her students expressed internal culture clashes with the material. “Frequently, parents who come from one culture to another very different culture become very conservative, preserving and propagating a conservative or limited version of the culture from which they came, ” she notes, and naturally passing their view on to their children.

“Generally, the classroom situation has been very nice, ” she adds. “South Asian students have taken the classes because they know they need to learn more that is objective. They are willing to learn, to hear an academic perspective or a historian’s perspective. The non-South Asians in the classroom have always been very much accepted by the South Asians.”

Julie Rajan, a colleague of Fazio at Rutgers, jokes that as an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins she was one of those Indian students (she was born in Madurai) who never considered taking a class related to Hinduism or South Asia. But she did find herself drawn to Indian literature and history and pursued such studies in grad school. She and Fazio were instrumental in increasing the number of India-related offerings at Rutgers. There she has taught Modern Literatures of India, Introduction to Literatures of India and South Asian Feminism.

“To assume that all Indians have any general idea about Indian history is not the right way to look at it, ” Rajan says. “Even within India, everybody has a different history.” She points out that Indian students include Muslims, Christians and Hindus from diverse geographic locations and backgrounds. She has never observed any conflict between those of different backgrounds. Rather, they are eager to learn and willing to admit it when topics arise with which they are completely unfamiliar.

A screening of Deepa Mehta’s film Fire, depicting the relationship between two women, did inspire strong emotions among students in Julie’s South Asian Feminism class. “We were discussing the way fire has been used as a way of testing a women’s purity in South Asia (such as in Ramayana). The movie Fire took the symbol of fire and read it through a feminist lens. Fire becomes a way of bringing out the power of women in society. Some students were perturbed by the movie, ” she says. “I find the students in America in some ways to be a little conservative when it comes to Hinduism. Some of them were not very open to even looking at alternate suggestions of perhaps feminism in South Asia.”

Narayanan took a decisive approach to gender issues–she wrote textbooks that include her extensive research about women. “I decided to go back and include women in every century, ” Narayanan says. “I used other people’s research, and if it didn’t exist, I did my own research. I included women philosophers who lived in the 14th century who were spouting the Vedas, and women mentioned in temple inscriptions.” She points out that though this evidence exists, these women are often omitted from historical texts. “That makes my students realize how idiosyncratic our sources of knowledge are. They really get into that, ” she says.

As more Indian students have enrolled in her classes, Narayanan has become acutely aware of how the practice of Hinduism evolves as people move from surroundings where they are in the majority to a setting where they are in the minority. She addresses this in her course Hinduism in America, which looks at Hinduism as part of American religious history. She is writing a book on the subject. Currently, she is also deeply involved in studying Hinduism in Cambodia. “What is it that Hindus carry with them when they migrate?” she asks. “What is it that they adapt? What is it that they discard? And what is it that they highlight?”

She says her studies have fueled her own sense of faith and belief. She is also constantly inspired by the energy and enthusiasm of her students. Sharma likewise says that studying Hinduism from an academic viewpoint has enhanced his own personal faith. “For me, one of the key ingredients of the Hindu view of life has been the attempt to seek out the truth, ” he says. “In seeking out the truth, I think it is really helpful to be challenged about the authenticity of what one comes to believe in naturally in terms of one’s inherited tradition. I found the academic study of Hinduism extremely stimulating for my faith, because the way Hinduism is represented is basically along Western lines. Western scholars do not normally share in the Hindu faith assumptions–so at least they claim. For me, all of this has been very useful because it helps me to address the question of the truth of the tradition more vigorously than would have been possible otherwise.”