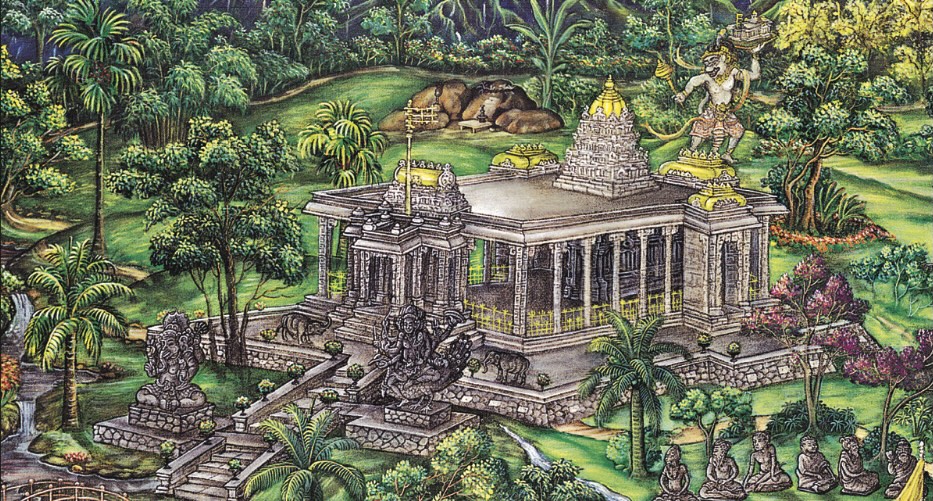

Untold centuries into the future, travelers will encounter a finely carved granite temple set like a gemstone on a Hawaiian island–one such as only the Tamil Chola kingdoms of South India could build. Puzzled, they may wonder what age, what civilization it belonged to. They will hear about a vision, a blaze of faith and a celebration of Hinduism that began in the late 20th century, and about a seed from the Tamil lands that sprouted far away.

Hinduism was not carried here by maritime traders or travelers but by a modern-day rishi, who–with the blessings of his Sri Lankan guru–created a Saivite citadel called Kauai’s Hindu Monastery and trained two generations of monks who aided him in his pioneering mission and live here still.

Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami (1927-2001), founder of Hinduism Today, is the spiritual genius that set it all in motion. When he first set foot on this site in 1968, Gurudeva, as he is affectionately called, realized how special the land is, charged with prana and palpable sanctity. He chose to make it the headquarters of his Hindu church and monastic order. A few years later, on February 15, 1975, he had an extraordinary experience. “One early morning, before dawn,” he recounted, “a three-fold vision of Lord Siva came to me. First, I beheld Lord Siva walking in a valley, then I saw His face peering into mine; then He was seated on a large stone, His reddish golden hair flowing down His back. This was the fulfillment of the quest for a vision of what the future might hold.” [See artwork on next page.]

In the Hindu tradition, there are two types of temples: those founded by men and those rare and most auspicious ones founded by the Gods through visions. Gurudeva explains how he seized the opportunity: “I felt certain that the great stone that Siva was sitting on was somewhere on our monastery land and set about to find it. Guided from within by my satguru, I hired a bulldozer and instructed the driver to follow me as I walked to the south edge of the property that was then a tangle of buffalo grass and wild guava. A tree deva directed my attention to a spot where there was a large rock–the self-created lingam on which Lord Siva had sat. A stunningly potent vibration was felt. The bulldozer’s trail now led exactly to the sacred stone, surrounded by five smaller boulders. San Marga, the ‘straight or pure path’ to God, had been created. An inner voice proclaimed, ‘This is the place where the world will come to pray.'” These visions inspired him to begin this exquisite temple, unlike any in the world. Since that day, pujas have been held daily at the spot, which will one day be sheltered with an elegant, open-air pavilion.

Today, 34 years later, the San Marga Iraivan Temple is a miracle nearing completion. It is a piece of India–its religion, culture, art and even the stones–manifesting on Kauai island. Each of the nearly 4,000 stones (the largest weighing 14,000 pounds) was hand-carved in India and then transported across the ocean to this Pacific island 8,000 miles away–about 80 container loads in all. Iraivan Temple is believed to be the only Hindu temple in the world moved block by block from one part of the globe to another. “Arguably the most elaborate Hindu temple in the United States” is how it was described in the Architectural Record by Brian James Barr, who noted that it is the only temple known to be entirely hand-carved in modern times.

During Gurudeva’s travels to South India in the early 1980s, he enlisted the services of Dr. V. Ganapati Sthapati, India’s foremost temple architect, who designed the temple strictly according to the Agamas and Vastu Shastras. Sthapati was especially inspired by Gurudeva’s edict to carve the temple entirely by hand, in the old way, without the use of modern machinery. To create it, in 1991 a small village was set up for 70 traditional sculptors, called silpis, and their families, in Madanayakanahalli, near Bengaluru. It was there, on an arid parcel known for its cobra snakes, that each stone was sculpted.

In Hawaii, rotating teams of six silpis (first brought over in 2001), helped by monks and local workers, have nearly finished assembling the temple. When complete, it will weigh 1,600 tons (3,200,000 pounds) at a cost of $16 million, which includes an $8-million endowment to permanently support the temple and its surroundings.

While Gurudeva decreed that ancient technology be used for the temple, his monks, dressed in hand-woven cotton Indian robes, used cutting-edge Macintosh computers to design the panel art that is found on many of the pillars to create a library in stone. Among other high-tech features, sunlight is channeled into the inner sanctum via fiber-optic cables, and web conferencing and iPhones are being used to coordinate every detail of the work. The new and the traditional dance together in Iraivan Temple.

The temple’s central murti is so rare that it may seem an innovation, but it is, in fact, of a kind lauded in olden scriptures. Iraivan’s inner sanctum enshrines the world’s largest single-pointed quartz crystal–a 700-pound, 39-inch-tall, six-sided natural gem, a sphatika Sivalingam that started growing 50 million years ago in a deep cave in Arkansas and was acquired by Gurudeva in 1987. Few know that such a crystal is, according to the Agamas, the most exalted of Sivalingams. Ganapati Sthapati explains, “In the Hindu culture of worship, Sivalingams are made of many materials, such as earth, wood, metal and gems. Among gems, the sphatika (quartz crystal) is considered very significant and sacred because it is spotless and transparent, like space. If all of the crystal Lingas in India were put together into one, they would still not equal the power of this one.”

Iraivan Temple is being built to channel and focus the spiritual power of this rare crystal Sivalingam, evoking the blessings of the Supreme God, Siva.

[pagebreak]

LIKE RISHIKESH OF OLD

Hindu temples in India are today mostly encrusted within crowded cities and towns, surrounded by the cacophony of automobiles and buses. Even in America, temples are often close to highways or a stone’s throw from strip malls, chain stores and fast food places. Today, alas, few devotees attending their neighborhood temple can approach the ideal described in the Krishna Yajur Veda, which says, “Find a quiet retreat for the practice of yoga; sheltered from the wind, level and clean, free from rubbish, smoldering fires and ugliness, where the sound of waters and the beauty of the place help thought and contemplation.”

Iraivan Temple is set in just such a perfect locale, one that seems to have been chosen by the Gods themselves–in the midst of a lush tropical forest on a Polynesian isle, with fresh water brooks and waterfalls all around, surrounded by a limitless expanse of sky and sea which changes from green to blue to indigo. It is built on the margin of the serene Wailua River, a pristine stream coming down from the nearby volcanic mountain. There are lotus-filled ponds, thousands of fruit-bearing and medicinal trees, and, with delightful frequency, inspiring rainbows arching above.

Iraivan Temple is a destination for serious pilgrims. Many have testified that they were never the same after their first visit, now understanding God, soul and world differently from ever before. “I’ve seen a thousand temples in India and the world. Of them all, this little temple on this little island stands out to me. It is the most beautiful. It is the most pure. It is actually divine. I can hardly believe it exists.” This quote is not from a celebrity or an intellectual powerhouse, nor is it from the shastras or saints. It is the voice of an ordinary devotee, unique only in her sincerity, a mother and a grandmother, an immigrant struggler who visited Iraivan Temple.

In the ancient Tamil language, Iraivan is an ancient Tamil word for God meaning, “He who is worshiped.” This temple is a pure celebration of Lord Siva. No other Deity is represented within its precincts. Everywhere one looks, in every direction, only Siva can be seen. Ganapati Sthapati pointed out that this is how all temples were built thousands of years ago.

Kumar Naganathan Gurukkal, a priest of the temple in Lanham, Maryland, who recently visited, effused, “I don’t have words to describe the temple’s architecture. After seeing it, my heart becomes single-minded, without desires and thoughts about the future. Generally temples are built as per the worshipers’ desire, but in Hawaii, the temple is built for the sake of the Supreme Lord.”

Gurukkal was delighted to see the abundance of the landscaped gardens surrounding the temple, with Indian favorites such as betel leaf, amala, bilva and areca trees, as well as rudraksha and konrai trees: “It is wonderful to see the forest of rudraksha, which grows in certain places only by God’s desire. It is not possible to plant and grow those trees anywhere except where the Lord wants them. Even in India, these trees grow only in remote places like Sabari Malai.”

Ravi Rahavendran from Carlsbad, Cali fornia, and his wife Sheela have been in love with Iraivan Temple from the first day they visited in 2003. Ravi shares, “The temple stretches back to the glory of ancient India.” He ponders, enthusiastically, “It is written in Saivite texts that one of Siva’s 108 holy abodes is Kovai. It is the only place of the 108 which cannot be located. Could Kovai be Kauai? It would not be surprising, given the sheer beauty of the island, the mystic vision and the location of the temple.”

[pagebreak]

BUILDING AS DIRECTED BY GOD

Deva and Gayatri Rajan of Canyon, California, have been devotees of Gurudeva for four decades. Deva emphasizes the divine origins of the temple: “Through the vision, Gods and devas were directly communicating with Gurudeva, directing him to have this temple built, and specifying how. The architect is one of India’s most revered builders of traditional Hindu temples. His plan follows the rules of the shastras, creating the perfect conditions for the mystical, inner workings of a Hindu temple to happen.”

Gurudeva directed that all aspects of the construction should be engineered to last a thousand years–an ambitious goal by Western standards, though many millennia-old temples persist in India today. The first challenge was to create a foundation that would last ten centuries and withstand earthquakes. The innovative expert Dr. Kumar Mehta, professor of engineering at the University of California, designed an amazingly dense 7,000-psi formula using fly ash, a coal by-product, reviving technology used in 2,000-year-old concrete Roman monuments. The result–a crack-free, 4-million-pound base using an auspicious 108 truckloads of concrete, and no rebar–was so successful that the project was showcased in Concrete Today, inspiring others, including the Swaminarayan Fellowship, to adopt the technology.

Having heard from Ganapati Sthapati that dynamite shatters the molecular matrix of the quartz in the granite and “kills the stone’s song,” Gurudeva made another decision: to use no explosives to quarry the stone, and no power tools for the carving, so as not to disturb the life force, or prana, in the stone. Therefore, only chisels–tens of thousands of them–and hammers are used for quarrying and sculpting. It is a laborious process. The chisels are made of relatively soft iron, because any harder metal would transfer the unbuffered impact of the hammer’s blow into the stones, causing unpredictable fractures. Chisels must be re-sharpened and re-tempered after just a few minutes of use. A blazing hot forge is used by the skilled silpis for the sharpening, and one gazing at their dexterous pounding on red-hot iron can feel transported to another age–for this was exactly how the grand temples of old were built.

The “chip-chip-chip” of chisels hitting hard granite that pilgrims hear around the temple site is the melody of a house for God being carved. When Gurudeva began negotiations for carving the stones in India, he heard murmurs that this song could be in its last notes. Nowadays, due to time and budget constraints, temples are, with rare exceptions, constructed of concrete and brick. A few use granite for the main sanctum, but even these employ machines for the main shaping, and hand chisels for the sculpting. Yes, even in India builders of holy places are asked to work cheaper and faster–hence to produce less elegant, less durable structures. Gurudeva understood that a temple carved by hand would be expensive and time-consuming. But he also knew that the most gracious work of the stone craftsman flows from his heart and his hands. Who could imagine Michelangelo’s David carved by power tools? And, in one very real sense, Iraivan Temple is a three-million-pound stone sculpture.

When Iraivan began, stone cutting was a dying art in India. Silpis were few and almost forgotten. But in recent years, there has arisen a new appetite for elaborate stonework in both temples and homes. This means that with the small pool of available talent, there is a constant struggle to obtain and keep the best silpis. Another managerial challenge in bringing this ancient craft to the modern age was the need to build the temple 8,000 miles away from the stone-carving site–usually the temple and the carving site are side by side. Coordinating such a ramified project has required expertise, patience, dedication–and no small amount of faith.

The expert and master builder in charge of the project is Selvanathan Sthapati, a fourth-generation temple architect from the family of Ganapati Sthapati. Selvanathan was given the responsibility to prepare detailed drawings and execute the site markings for the silpis to carve the stones at Bengaluru, as well as the technical markings for the jointing work by carvers on Kauai. For Selvanathan, working on Iraivan Temple is a mystical experience. He likes to quote Gurudeva’s original intent: “From the beginning, the temple was conceived to be as rare as the vision that birthed it.”

Selvanathan remembers,”Many years ago, Gurudeva gently took my hands into his and blessed me to be a sthapati of this project. Ancient scriptures of our craft say that ‘a silpa (sculpture) exists inside the silpi (sculptor), and then silpi turns into silpa,’ evoking how a silpi experiences the Divine form within himself as he carves it on the outside.”

Such mastery in all details has a tangible effect. “More and more I am seeing the temple not as a building as much as a gigantic sculptural masterpiece,” says Paramacharya Palaniswami, editor-in-chief of Hinduism Today. “It is more art than architecture, more spirit than matter, more heavenly than earthly–though it is all those things. It is about art as devotion, art as technical craft, art as skilled energy, art as sacrifice, art as vision.”

A unique touch, he adds, are 240 bas-relief stone panels on the pillars, telling in pictures and potent aphorisms the temple’s story and the essence of Saivism. It is a library forever set in stone. A walk through the temple is a walk through India’s great spiritual and cultural ideals, touching upon Hinduism, karma, reincarnation, states of consciousness and the yogas. Carvings teach about the various forms of Siva, about medicinal and sacred plants from India and Hawaii, meditation maps and so much more. Sheela Rahavendran dreams, “I can hardly wait to see pilgrims walking with their children from pillar to pillar, explaining a great many beautiful things about this temple, about its founder, and about Hinduism in general.”

Palaniswami explains that the team in Kauai is now working on the final stages of the main temple: installing the rose-colored granite flooring stones and the lotus hand rails. In India, carving is underway on the Nandi Mandapam, a relatively small, but exquisitely elaborate, 16-pillared pavilion which will be the home for Nandi the bull, Siva’s mount. The final stone works remaining to be done are the outer courtyard wall and steps down to the Wailua River.

“Since Iraivan Temple has been designed to last for so long,” explains Deva Rajan, “utmost care is being taken to use the finest and most durable stone and materials. Workers are advised to ‘slow down’ and ‘do the very best work that you can ever do’–advice seldom given to artisans on a worldly project. Where else on Earth do we find such goals as these?”

Alluring as the job might be, hiring is not easy. One doesn’t find traditional Hindu stone carvers for hire in America, without whom the temple construction would be impossible. Bringing silpi talent to America has been difficult, especially with post-9/11 security and visa issues. When visas for the sculptors were repeatedly and wrongfully denied in 2007, threatening the closure of this and other US projects, the swamis in Hawaii led the American Hindu community in pressing for regulation changes to reflect America’s growing religious diversity, acknowledging silpis and other occupations related to Hindu practice as qualified for the Religious Worker visa program. Palma Yanni, a prominent, expert immigration attorney in Washington, D.C. was hired, and other Hindu organizations engaged. The Hawaii swamis traveled to Washington to press their case with Senators and Representatives, orange-clad renunciates laboring in the halls of temporal power. They succeeded, and the resulting immigration policies reflect their concerns and are broad enough to accommodate most Hindu needs. Happily, the masterful, graceful carving of Iraivan Temple can continue.

[pagebreak]

FROM THE HEARTS OF PILGRIMS

Many visitors say that once they are touched by the mystical impulse that is creating this temple, a love develops for the project and the building itself. For many, it has meant a rediscovery of their connection with Hinduism, sometimes sparked by an encounter with the founder, Gurudeva. Pilgrims come from everywhere–from India and from countries of the diaspora, as far as Hong Kong, Australia and South Africa.

Manon Mardemootoo, a senior attorney practicing in the Supreme Court of Mauritius, says though he was born in a religious Hindu family, he came to appreciate Hinduism only after meeting Gurudeva and learning from him. Ever since, Iraivan Temple has been part of his life: “We were there in 1991 at the first chipping ceremony at Kailash Ashram, in Bengaluru, in the presence of many saints. Since then we have been following the progress on works both at the Bengaluru carving site and at Kauai, which we have been visiting regularly.” In his heart, of all the temple’s features the main murti stands unrivalled. “The main sanctum’s sphatika Sivalingam is worthy of a deeper understanding. Crystals are known to possess intelligence and qualities yet to be discovered.”

Mardemootoo is a “temple builder,” one of a dedicated group of people on several continents who devote part of their lives to making Iraivan Temple manifest, both with fund-raising and personal support. He takes this job seriously. “We feel particularly privileged to be ‘temple builders,’ as it is the greatest assignment which can be entrusted to us humans. The more people participate in spiritual endeavors, the more our planet benefits–which is presently very much in need of love and protection. I feel happy to be part of this project; it’s like being on a holy adventure, led by our loving Gurudeva, into our Self and the inner worlds.” His whole family is involved, along with sponsors and well-wishers they have introduced to the project. Mardemootoo adds, “We are all looking forward to the mahakumbhabhishekam (consecration ceremony) of Iraivan Temple, an auspicious day, a tremendous source of power for all.”

The Rahavendrans from California shared how they were touched by the weave of selfless monasticism and sincere worship that pervades Kauai’s Hindu Monastery. Sheela Rahavendran recalls that she was overcome with emotion, just facing Lord Murugan, Ganesha and Siva in the monastery’s 36-year-old Kadavul Temple, and could not get up to leave. After their first visit, just a few years ago, they took God’s blessings home and allowed that energy to change themselves and their lives. After Sheela’s return to California, a major transformation occurred. “I became a vegetarian, just like that–no meat, eggs or fish, and I have been that way ever since.” Kauai became a lifelong love. “The journey on San Marga, the straight path through glades and streams leading to Iraivan Temple, is a metaphor for the evolution of the soul unto its potential. It serves as an inspiration for self transformation in this lifetime,” notes Sheela. “There, spiritual upliftment is felt in every pore of one’s being. Sheer sattvic energy begs the devout Hindu to return time and time again on pilgrimage to Kauai.”

Iraivan Temple is a sanctuary for Hindus, but here people of all faiths report experiencing a sense of a divine presence. A local Christian minister told the monks, “This is the first time I really feel I am walking on holy ground.” Dr. Nilufer Clubwala, a pediatrician in Campbell Hall, New York, and Zoroastrian by faith, has been inexplicably drawn to Iraivan Temple. “My first experience of Iraivan Temple was in a vivid dream I had many years before my first encounter with Gurudeva. It was a sparkling white temple pulsing with an energy I had never felt before. Several years later while in Kauai, walking around on the temple grounds, I recognized this to be the very place that I had seen in that hard-to-forget dream years ago. As in the dream, I was suffused with the energy of the place. Pure, powerful and vibrant. No words of description can do it justice–it has to be experienced.”

Since then, Nilufer and family have made it a point to travel to Kauai every year, watching the temple rise up. She notes, “What makes this temple so special to me is the fact that so much more than granite has gone into its making. It is the love, time, contributions and energy of the devotees and friends of the temple, the unending dedication of the monastics who manage its construction, and the hard work of the silpis as they tirelessly chip away at the granite. All these factors magically come together as we see Gurudeva’s vision take form as Iraivan Temple.”

Though it will be a few years before the main structure of the temple is completed, pilgrims come in a steadily growing stream to experience the sanctity, which, many attest, is already there.

[pagebreak]

A STRONGHOLD OF SAIVISM

The long-term planning and daily functioning of the temple is managed by the Saiva Siddhanta Yoga Order. For Ravi Rahavendran, the monks’ involvement with the project is key to his enthusiastic support: “Their presence enables a strong and continuous connection to the inner worlds.” As Deva Rajan points out, “Unlike the ever-changing boards of directors that manage most Hindu temples, this monastic order brings to the management a consistency and stability that is free of politics and personal motives.”

Ravi is amazed that since March 12, 1973, the monks have been conducting pujas every three hours, 24 hours a day, at the smaller Kadavul Temple, located at the heart of the monastery. That’s over 36 years without missing a single puja, eight times a day. For this reason, Ravi states, “One can actually experience divine energy here.” By the time this issue of Hinduism Today arrives on the newsstands on July 1, 2009, the monks will have performed 106,069 uninterrupted vigils (three-hour spiritual watches each takes by turn), building up the vibration.

While Iraivan is the jewel of Kauai’s Hindu Monastery, several other initiatives upholding dharma are driven by the monks. It is from the monastery that Hinduism Today is published each quarter; books and pamphlets are created and distributed, and the multi-million-dollar Hindu Heritage Endowment is managed as a public service for Hindu institutions worldwide.

Every task–be it looking after the land, tending to the monastery’s gentle cows, supervising the building of the temple or publishing books and magazines about the Sanatana Dharma–is an act of devotion by the monks. Gurudeva left in writing: “What makes the San Marga Iraivan Temple, the moksha sphatika Sivalingam, our small and large shrines and publication facilities so special is that they are part of a monastery, or aadheenam: the home of a spiritual master, a satguru, and his tirelessly devoted sadhakas, yogis, swamis and acharyas. Moreover, this Aadheenam is a theological seminary for training monks from all over the world to take holy orders of sannyasa and join the great team of our Saiva Siddhanta Yoga Order. From the world over, devotees pilgrimage to Kauai Aadheenam, our headquarters. From here Iraivan’s sphatika moksha Sivalingam shines forth.”

[pagebreak]

GIFTS OF LOVE

The building of Iraivan Temple, a project so complex in scope and details, entails boundless time and enormous expense. It is the generosity of thousands of devotees that has been making this vision a reality. Gurudeva directed that the temple be built without any debt. That means that efficient and continuous fund-raising is a must.

Palaniswami recounts, “We have raised $12 million toward our $16-million goal. Though we have received a handful of large donations, by far the majority of all funding has come in the form of small, regular donations from our 12,000 contributors in 58 countries around the world.”

In Gurudeva’s trips to India, he saw many majestic temples that had fallen into neglect, with too little funding to maintain them, staffed by a handful of underpaid priests. Determined that Iraivan never suffer that fate, Gurudeva established a maintenance endowment, stipulating that half of every dollar donated go into that endowment. In this way he ensured that Iraivan Temple will continue to flourish in the future. Once the temple is consecrated, the endowment will be $8 million, providing sufficient income that the monks will never again have to raise funds to care for the temple. Iraivan’s endowment has been set up so that its principal cannot be spent under any circumstances, but generates income year after year.

Sannyasin Shanmuganathaswami, the monastery’s financial administrator, describes the fund-raising efforts: “First, Gurudeva concentrated on paying off the land. It was the late 80s before we started raising funds for the building itself. Fund-raising was hard in those days because there was no actual building to point to. Starting out with just a few close devotees, the monks used the modern tools of technology to get the word out.” Swami explains that ground-breaking technology was, to his guru, a wonderful tool for productivity that he enthusiastically embraced. Gurudeva might even have created the world’s first photo blog in 1998, when he instructed his monks to post photos and daily news–before the word blog was coined. This daily news site is called Today at Kauai Aadheenam, or TAKA.

The monastery has a user-friendly, resource-rich website (www.himalayanacademy.com [www.himalayanacademy.com]) with vivid images and text bringing Iraivan Temple into the homes of devotees. Contributions have come from people who have never set foot on Kauai. The list of countries involved is astonishing. One might ask, does it include faraway places such as Norway? Yes it does. What about mother India, colorful Guadeloupe, Brazil, Mauritius, Trinidad, Australia? Yes, donations come from those places as well. No country is too far for Siva’s devotees to be touched by the dream of Iraivan Temple. For them, instantaneous darshan available with a click of the mouse is important. On TAKA, these virtual pilgrims in faraway lands can see, day by day, Iraivan rising with their contributions. They hope to worship, one day, at the temple they are helping to build.

Most temples are based around a local community and are a reflection of its population. In contrast, Iraivan has a global flavor. This has been motivating, especially for Hindus outside of India who resonate to the pure Saivite tradition that thrives in this place of tranquility and peace. Wherever they live, however troubled the times or the region, they find solace in the fact that on Kauai things are right with the world.

The monastery’s printed newsletter has also been a vital tool in getting the word out, since it lists everyone who has given to the temple in the previous month, as well as the total raised. This inspires people who are new to the project to start giving regular donations to help bring Gurudeva’s vision into manifestation. “It has worked well, and it has set a model for other temples on how to keep in touch, as a well-knit family weave,” Shanmuganathaswami attests.

Malaysia plays a special role in this project. Dedicated Malaysians, constituting one-third of the sishyas of Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami, Gurudeva’s successor, have shown their commitment by raising funds to cover the cost of Iraivan Temple’s rose-colored floor. Malaysian devotees are creative fund-raisers, holding lively meetings and engaging in projects such as producing key chains to sell, with pictures and Saivite motifs, usually a photo of Gurudeva.

Personal stories color each pound of stone. Nageswaran and Rajeswari Nagaratnam of Sydney, Australia, volunteered to fund the carving of the gomukai–the stone that holds the water pouring out from the sanctum after an abhishekam–becoming the first, in February, 1993, to sponsor a single temple artifact. Another sponsor donated $108,000 for the capstone. Faithful Nandi, Siva’s sacred bull carved in black granite, was sponsored by devotees from Singapore. Most donations come in the form of an ongoing pledge, setting up an automatic charge on one’s credit card or bank account for a modest sum every month. The constant flow such donations bring is key to the project’s stability.

Shanmuganathaswami tells us there are ways to support a Hindu temple with money that would normally be paid to the government in the form of taxes. “We’ve been encouraging people to put the temple in their wills. We hired a planned giving consultant to help devotees write effective estate plans to help their family finances as well as the project. It’s a situation where everyone wins, but few people realize they can make their legacy continue to work for what they cared for in life.” Many people remember the temple in their wills. One donor took out a $750,000 life insurance policy, making Iraivan Temple the owner and beneficiary.

Iraivan Temple’s fund-raising is not immune to bad economic times: the Hindu Heritage Endowment suffered losses in 2008, along with everyone else. But Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami assures, “For us, what matters is the long-term performance. When the market eventually comes back up, so will our endowment’s assets.” We can all learn from a monk’s patience, and for a temple being built to last for a thousand years, this certainly rings true.

[pagebreak]

A PLACE OF PILGRIMAGE TODAY

While Iraivan Temple’s consecration ceremony is a few years away, even today, many families make this holy spot the destination of their pilgrimage, with the goal of worshiping in Kadavul Hindu Temple. This powerful sanctuary, founded in 1973, is a fire temple, said to burn karmas, enshrining a 6-foot-tall bronze, Lord Nataraja Deity. There, surrounded by 108 golden dancing Sivas, pujas are held every day at 9am. Pilgrims can be seen walking the monastery’s peaceful grounds, meditating by the river or worshiping at the site of the svayambhu Lingam.

Visiting pilgrims ask, “When will the temple will be completed?” As the monks like to say, there are no deadlines–the temple will be completed when all the money is raised. At the current rate of progress, the temple will be consecrated and opened for worship around 2017.

Speaking from the intuitive state of awareness he called the “inner sky,” Gurudeva expounded his heart’s vision for the temple: “Iraivan Temple, with Lord Siva facing south, is a moksha temple. This means that being in the presence of its sanctum sanctorum brings the pilgrim closer to freedom from rebirth on this planet. The vibration of the temple wipes away the dross of the subconscious vasanas and simultaneously heals the wounds of psychic surgery. It takes away encumbrances and releases the pristine beauty of the soul. As pilgrims leave the San Marga Sanctuary, they carry away with them a new self-image and a clearer understanding of the purpose of life on planet Earth. Here, Hindus find the center of themselves.”

[pagebreak]

BREAKING GROUND

On April 4-5, 1995, a grand ceremony, called Panchasilanyasa, brought priests and devotees from around the world to the site of Iraivan Temple for the placement of five sanctified bricks in an underground crypt, along with a cache of gems and other treasures. Warm Hawaiian breezes enveloped the faithful in a gentle embrace. Camphor, incense and flowers spoke to their senses as did the tintinnabulation of the bells and sonorous Sanskrit, chanted loudly by vibhuti-smeared priests. Deva Rajan shares his experience of the event.

“Many priests were there from Chennai for the homa, including the respected Sivasri Sambamurti Sivachariar, who officiated the Hindu rituals, along with architect V. Ganapati Sthapati. A four-by-four-by-foot square pit had been dug at the northeast corner of the future inner sanctum of the Iraivan Temple. In the pitch black of the hours before dawn, no one could tell if we were in India or in Hawaii. With great ceremony, my Gurudeva, the Hindu priests, the architect and others installed sacred substances into the pit–gems, gold, silver, rare herbs and other auspicious items. Tray after tray was carried by the monks to be placed. At one point, a large pot of vibhuti (holy ash) was poured into the pit; hence any further offering drew clouds of vibhuti floating out of the hole, blessing us all.

Under the tranquil light of the moon, Sambamurti Sivachariar, together with Gurudeva, frequently waved the glowing camphor flame. In bursts of powerful sacred chanting, the pit was consecrated. Master architect Ganapati Sthapati placed five sacred bricks engraved with the letters na ma si va ya in Tamil.

After these rich and abundant blessings, Gurudeva directed a few of us to seal it all off with concrete. As the crowd dispersed, we mixed several wheelbarrows of fresh concrete and poured it into the pit. When the task was complete, with joyous hearts we drifted away, knowing we had participated in a rare and magical event that would stay with us forever.”

[pagebreak]

THE PATIENT SCULPTORS’ SKILLS

The chipping sounds rarely stop as chisel and hammer pummel the reluctantly yielding stone. It is more a form of erosion than carving, a slow pulverizing of the granite a few hundred molecules at a time. Millions and hundreds of millions of blows by the sculptors slowly reveal the design. It is a labor of love requiring a level of patience that few are capable of, and thus the rarity of it all. To onlookers, this seems an impossibly tedious task, but carvers say it brings a greater reward–after all, this is God’s work. One single piece can take three or four men three long years to complete, and any serious mishap will put the work to waste.

Make no mistake, these artisans know their stone. While finishing work needs but a delicate etching of a fine-pointed chisel, basic shaping requires powerful blows that will cut open large boulders in minutes. The skilled silpis know the full range of the creative process, learned by most at their father’s knee.

How a temple evolves from raw stone to finished art is a story of stones, chisels and the blacksmith’s fire. The sthapati is the architect who designs and guides the transformation of raw granite into iconic statues and mighty temples, aided by an army of silpis or sculptors. Based on his precise design and markings, the silpis shape the stones to perfection.

The stones are then maneuvered, lifted, nudged together and finely fitted, the goal being the famed “paper joint,” so tight the thinnest paper cannot find the space between them. Laden with the devotion their creators’ impart, graced with the design of ancient wisdom, the stones merge, one by one, to create the massive temple structure. Alone they are marvelous works of art, but together they possess the power to contain God Himself, to be His body and His home.

This traditional knowledge, training and skill is passed from father to son, and each generation is initiated into this sacred art in childhood and youth. Iraivan Temple’s Selvanathan Sthapati, who inherited this wealth of knowledge from his paternal uncle and father, relates, “I was brought up in a home filled with the sound of chisels and hammers. Even as a child I learned the skills by watching the moves at our pattarai (workshop). Early on, I began exploring the nuances and curves of traditional designs that would be my lifelong occupation, and my legacy.”

[pagebreak]

ARTFUL WONDERMENTS

A wish-fulfilling crystal, whimsical musical pillars, powerful lions and a giant stone bell. These are among the awe-inspiring features that spark the pilgrim’s humility, elevate his thoughts and surround him in his divine quest.

Iraivan Temple emulates the architectural style of South India’s Chola empire, which reached its zenith 1,000 years ago. Crowning the temple is a giant 7-ton monolithic capstone that took four men three years to carve. Hanging at each of the temple’s four corners is an eight-foot-long chain, with graceful 14-inch links, impossibly carved from one block of granite (pictured on the left).

A 32-inch-diameter stone bell rings like metal when struck with a mallet. The wooden doors to the main sanctum are elaborately carved with ten forms of Siva and hung on an ornate black granite frame.

The Sivalingam is the largest single-pointed quartz crystal on earth. Its traditional five-metal base weighs nearly 10,000 pounds and is the largest cast in modern times.

Carvers will chisel two musical pillars from black granite, each 5 feet wide and 13 feet tall. From the massive stone which forms the central portion, craftsmen will carve out sixteen 4-inch-wide, 5-foot-long rods which, when struck, will resonate musical tones. Between the 16th and 18th centuries, just three South Indian temples were built with musical pillars. Iraivan will be the first temple outside India to have these rare artifacts, which are used by musicians to tune their instruments.

Guarding Iraivan’s entrance are two yalli sculptures representing inner-plane beings who are a magical combination of seven animal species. Six lion pillars supporting three surrounding towers complete the temple’s inner-plane guard. As if to show off the silpis’ skill, each lion holds in his mouth a three-inch stone ball, which children love to turn with their hands, though no amount of cajoling will release it!

On the north side of the temple stands a stately statue of Siva as Dakshinamurti, the South-Facing Lord, Universal Guru and Silent Preceptor, teaching four sages seated before Him. The noble black granite Nandi, Siva’s mount, will be enshrined in a 16-pillared pavilion in front of the main entrance, not far from three stone elephants who are climbing the steps to see Siva.

Visitors to Iraivan will be intrigued to learn that there are treasures even beneath the temple. Hindu temples traditionally have copper plates stored in a rock crypt sealed in the foundation, recording the history of the temple’s creation and the times. Iraivan not only has these but also a modern argon-gas-filled stainless steel canister containing present-day artifacts. Scheduled to be opened 1,000 years from now, these two time capsules will reveal to future generations a treasured record of the philosophy and culture of Hinduism, and of how Hindus lived and followed their faith.