In 1996, Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor, then 37, was immersed in a successful career at Harvard and a long history of brain research. She was a neuroanatomist with a passionate drive. Her brother suffers from schizophrenia, and she dedicated her life to the study of brain disorders, trying to understand why he, unlike her, could not share the common perception of the world that most people call “reality.”

Dr. Taylor’s research focused on investigating the chemicals that cells use to communicate with other cells. Her team tried to identify the biological differences between the brains of individuals diagnosed as normal and the brains of those diagnosed with schizophrenia, schizoaffective or similar disorders.

To identify what makes brains different, one needs, well, brains–specimens to dissect, compare and catalog. Those who have relatives with mental disorders and ardently hope for a cure are the ones whom the scientists seek out, because they can authorize the donation of organs when their relatives die.

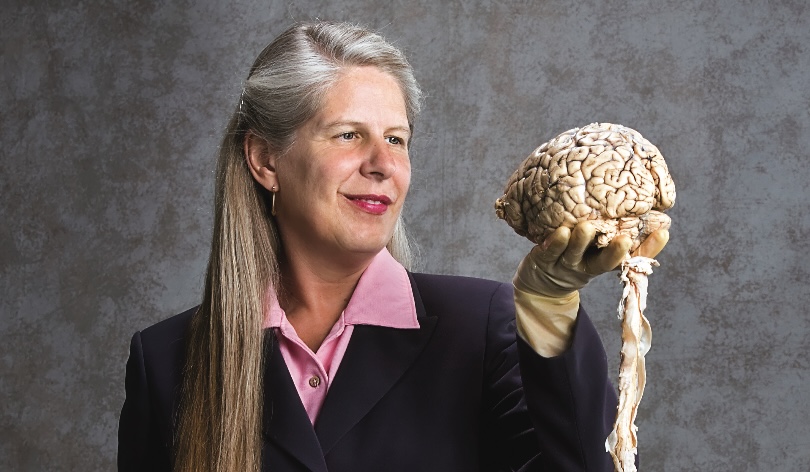

In the mid-1990s, Harvard’s “Brain Bank” had barely enough donations to keep research going. Wanting to help, Dr. Taylor embarked on a mission that, she says, gave her life a lot of meaning. It included the peculiar task of asking people for their brains, while politely assuring them she was not in a hurry.

Music, she learned, could break the ice. Carrying her guitar around the country on weekends, the “singing scientist” crooned compositions of her own: Oh, I am a brain banker / Banking brains is what I do / I am a brain banker / Asking for a deposit from you! // When you are heaven bound / your brain can hang around/ To help humanity find the key / to this thing we call insanity.

She led a purposeful life, successful and happy–when on the morning of December 10, 1996, an artery in her brain exploded, propelling her into unexplored inner worlds and nearly an untimely death.

A “STROKE OF INSIGHT”

Dr. Taylor describes the morning of the stroke and the approximate time of events:

“I woke up to a pounding, caustic pain behind my left eye. It was very unusual for me to experience pain, so I just started my normal routine. I got up and went on to exercise on my full-body exercise machine. When I looked at my hands grasping the handles, they seemed such primitive claws. ‘That’s very peculiar,’ I thought. I looked down at my body to find myself to be a weird-looking creature.” Dr. Taylor was not identifying with her body anymore. “My consciousness had shifted away from my normal perception of reality. I was not the person having the experience. Instead, I was witnessing myself in the third person.”

She continued as if it were just a passing disarray. “With my headache getting worse, I walked across my living room, realizing that my movements were rigid and very deliberate.” Because her external perceptions were contracted and confused, she reached for the inside of herself. There, she was astonished at what her mind could sense. She was no longer a single organism alone in the room. She had become an agglomerate of life. “I was momentarily privy to a precise understanding of how hard the fifty trillion cells in my brain and body were working. I heard the orders that made one muscle contract, the other one relax, working in perfect unison. I witnessed in awe as my nervous system calculated and recalculated every angle. I was each of my cells, each molecule of the thriving sea inside my skin.”

On her way to take a shower, balancing her weight against the bathroom wall, Dr. Taylor realized she could no longer identify the boundaries of her body. “I could not define where I began and where I ended, because the atoms and the molecules of my arm blended with the atoms and molecules of the wall. All I could detect was pure energy everywhere.”

Asking herself what was wrong, she received no answer, no thought. The question itself faded. Then the mental chatter we always hear in our minds–the verbal decision-making process, the dialogue of our thoughts–was gone. Her mind was a still lake, a vast and silent void.

Silencing the mind flow and stilling thoughts to a perfect quiescence is a common goal in meditation. Hinduism and Buddhism describe this as a spiritually desirable state. Yogis use pranayama (breathing techniques), body postures, japa (repetition of mantras) and efforts of will to gradually achieve it. In Dr. Taylor’s case, her brain took her there in a flash. She thought she had lost herself somewhere along the way. Who was she, if not the voice in her head? But even though she was not thinking in verbal constructs, she was still fully aware. “I was conscious in my mind. I was fully present, and now was the only moment. At first I was shocked to find myself in a silent mind. But then, almost immediately I was captivated by the magnificence of energy around me. I felt enormous, expansive. I felt at one with all energy, and it was beautiful.”

Human brains have two hemispheres, completely separate except at the corpus callosum at their base. Scientists understand that our personal identity is defined entirely in the left lobe of our brain, while the right lobe has very different functions, different thoughts, different priorities and even a different way of processing information. Dr. Taylor’s left-lobe stroke was affecting the home of the ego, that which in Sanskrit is called ahamkara, “I-maker,” man’s finitizing principle. Without it, as she puts it, she was no longer I, but we.

The hemorrhage was drowning the neurons that civilized humans are most familiar with, those in the left hemisphere. There we store all of our opinions, rearranging them to form new ones. In our intellectualized modern life, the aggregate of our memories and opinions is a common way to define ourselves, thus its connection to the ego. The left side analyzes, ponders, categorizes and measures the immense amount of information it receives from the senses and from the right brain. It thinks in language and words, linearly chaining facts and conclusions. It remembers the past and speculates about the future. It connects humans to the external world, remembers to pick up the laundry on the way home and responds to our given name. It makes us solid individuals, separate from the whole.

Dr. Taylor was cast into a very different area of her mind. With the left hemisphere offline, she was free from the clutches of the intellectual mind and experienced her right hemisphere fully. It had never been off–actually, it predominates in babies, but remains obscured throughout adult life. In the right brain, only the present exists; there is no past and no future. Information in the form of energy streams simultaneously from all senses, exploding into an enormous collage of what a moment looks, feels, tastes like. The right lobe thinks in pictures, abstractions, kinesthesia and physiological input. It is not judgmental; nor does it understand limits and separativeness. It is about oneness, harmony and relating everything in a vast, intuitive understanding. Lost in that realm, Dr. Taylor was enraptured by the silence, the clarity of her consciousness and the bliss. But she could still be reached by bouts of severe pain.

Suddenly, in a spasm, her left hemisphere gathered enough resources to urge, “This is not normal. I am in danger.” But that was all it said. Unable to think of what to do next, she drifted back into right-hemisphere consciousness. A pristine detachment from the world emerged in her. “All stress was gone. I felt lighter in my body. All my relationships in the external world and their pressures ceased to be. Imagine what it feels like to lose 37 years of emotional baggage! I felt peace and euphoria.” And with no sense of time, her newly found freedom seemed to last forever.

Untethered, she realized her body was an extraordinary, but temporary, home. “In the wisdom of my dementia, I understood that this body was, by the magnificence of its design, a precious and fragile gift. It was clear to me that it functioned like a portal through which the energy of who I am can manifest here. I wondered how I could have spent so many years in this construct of life and never realize I was just visiting.”

With effort, she dressed for work. But faced with a paralyzed arm, she finally understood the situation. “I’m having a stroke!”–immediately followed by, “Wow, this is so cool!” For a brain scientist, studying her mind from the inside was the ultimate opportunity. Conscious enough in her waning left lobe to know she needed care, she went to call for help. But between each number she dialed, her consciousness expanded into heavenly bliss and overpowering tranquility, making it laboriously challenging to remember what she was trying to do–or which number was next.

She was lost in an existence of love and expansiveness, of color and energy. She felt atoms and molecules in a dance of swirling light, connecting her to all beings. But while she waded in bliss, an intense pain gripped her body in an irreconcilable dichotomy. Dr. Taylor was enticed by the allure of surrendering to it all, and letting go of life. “A piece of me yearned to be released from captivity. Providentially, in spite of this unremitting temptation, something inside of me remained committed to orchestrating my rescue.” Finally, she managed to call her workplace, reaching a colleague who recognized her voice.

In the ambulance on the way to Massachusetts General Hospital, humbled by her condition, she curled up into a fetal ball. Still acutely aware, she remembers feeling “just like a balloon with the last bit of air blowing out of this vulnerable container. I felt my energy lift; I felt my spirit surrender.”

At the hospital, her condition was stabilized by the medics. Waking up, she was shocked to still be alive, but remained in a state of bittersweet altered consciousness. Sensory stimulation was painfully amplified. Light burned like wildfire and sounds disintegrated into chaos; while at the same time a harmonious sea of silent peace flooded her nervous system. She was unable to worry. All she could do was to be in an eternal now.

She describes soaring as a being with no boundaries, expanding far beyond her body. “I was like a genie just liberated from her bottle. I remember thinking I would never be able to squeeze the enormousness of myself back inside this tiny little body. I was one with the vastness of the universe.” Three-dimensional space and time were inexistent. She remained in a state of pure being, of unfettered consciousness and constant bliss. Any Hindu might wonder if this was the yogi’s sat-chit-ananda, “existence-consciousness-bliss.”

People, she discovered, could bring good energy or take it away. She was oblivious to the meaning of words but could understand the intention behind them. In a touch, she could feel the love–or disdain–of any nurse or relative. Though mentally disabled, she was not unintelligent, only injured.

Trying to identify her state, she wondered if it was the Buddhist’s nirvana. She reasoned, if she was alive and had found nirvana, then everyone else could, too. That was something worth living for. “I pictured a world filled with beautiful, peaceful, compassionate, loving people who knew they could come to this area of their minds at any time. They could purposely choose to step to the right hemisphere and find this peace. I realized what a tremendous gift this experience could be, and that motivated me to recover.” After two weeks, a surgeon removed a golfball-sized blood clot from Jill’s brain. It took her eight years to regain her normal faculties. It was a spectacular and rare recovery, aided by the unremitting care of her mother, Gladys Gilmann, for whose persistence, love and respect in helping her heal Jill spares no praise.

A NEW LIFE

Slowly a different person emerged from the cocoon of the stroke patient Dr. Taylor had been. She had to re-learn things much like a baby. Rebuilding her mind was an enormous task, but as a mature adult, she could watch over the process and make decisions.

When we are born, both hemispheres are equal, Dr. Taylor told Hinduism Today. The left hemisphere begins to change rapidly as we develop an analytical intellect, while the right hemisphere stays approximately within its original frame.

When a thought or an activity is performed repeatedly, the brain readjusts neurons to form a highway on which that impulse can travel with the least expenditure of energy. Synapses, as the connection between neurons are called, line up in a chain of minimum effort and maximized performance. In our brain, connections reflect our habits and patterns. That is why familiar thoughts are so much easier to reevaluate than new concepts; that is why we can mechanically perform complex tasks such as driving or talking.

But with many of her synapses gone, Dr. Taylor was free to consciously choose to not rebuild some of her old mental bridges. She loved to now realize she was a fluid beam of energy, not an organic object. She loved to experience being one with the universe and with everything–and everyone. Most of all, she loved the deep inner peace that flooded the core of her being.

One uneasy doubt tinted her enthusiastic dedication to recovering, which she explains by quoting peace activist Marianne Williamson, “Could I rejoin the rat race without becoming a rat again?” Dr. Taylor pondered, “Could I value money without hooking into to neurological loops of lack, greed and selfishness? Could I regain my position in the world while retaining compassion and a perception of equality among all people? Frankly, I would not want to lose touch with my authentic self. What would be the price to pay to be considered normal?”

It was essential to maintain the dominance of the right brain in areas it performs better that the left. In her quest, Dr. Taylor painstakingly worked out a way to never let go of her beautiful, right-brain new world. She consciously avoided certain places in the mind where impatience, worry, criticism or unkindness live. Anytime her awareness drifted there, she consciously stepped over to her now-familiar right side, where compassion and a subjective sense of time make things very different. With new neurological pathways, she says, she began rediscovering the world with childlike curiosity and joy.

Under-used, the circuitry of her ego never regained its full influence. Still, she assiduously tends her “mind’s garden,” setting aside a day every week for her authentic self–a silent day of right-brain consciousness. And she also nourishes it with music, guitar-playing and stained glass art. She finds it most importantly, though, to constantly arbitrate between the two sides within. She might, for instance, inwardly address her worrying left mind, enunciating that though efforts to alert her of real danger is welcome, anxious thoughts are not needed and can stop–thank you very much!

UNEXPECTED FAME

On the road to her recovery, Dr. Jill Taylor rebuilt her career as a scientist. She resumed lecturing even before she could understand addition and subtraction again. Though she can no longer vivisect any living creature, she became ever more fascinated with the brain. Today she works with the Indiana University School of Medicine and is a national spokesperson for the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center.

Dr. Taylor wrote a book recounting her experiences, A Stroke of Insight (Viking, New York, 184 pages). It is an intimately personal tale, not a medical dissertation on recovery. The last two chapters discusses how to tap into the potential of the right brain. She nearly deleted the material from the manuscript, afraid that it sounded too much like metaphysics and too little like science, with instructions like “our desire for peace must be stronger than our attachment to the ego.” Feeling brave, she decided to publish it anyway, hoping her experience will help others.

“Unfortunately, as a society, we tend to not teach our children to tend carefully to the garden of their minds. Thoughts run rampant and redundant,” she explains, underlying the need for simple weeding. Because we are never taught to identify our inner conflicting opposites, we tend to think we are ourselves conflicted. “Thanks to my stroke, I have learned I have the power to stop thinking about events that have occurred in the past by consciously aligning myself with the present.” It is a decision she says she has to make a thousand times a day.

An irresistible wave of change swept through her life in January 2008 after she shared her journey with a select group at an event called TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design), an annual conference which uses the motto “ideas worth spreading.” The presentation was so engaging that the audience of scientists, politicians and intellectuals gave her a standing ovation. It was soon posted on the Internet, where it became an instant and unexpected sensation: 250,000 people saw it within the first 24 hours (www.ted.com/talks/view/id/229).

Suddenly, Dr. Taylor became famous in a way she had never imagined. A simple airplane trip would have people approaching her to shyly express appreciation. She was invited to give an interview on Oprah, America’s gateway to popular recognition, and the video of her lecture was posted on Oprah’s website. Time magazine chose her as one of the 100 most influential people in the world for 2008, and The New York Times published an article on her experiences entitled “Superhighway to Bliss.”

Judging by the content of those articles, most of the interest has been medical: people want to hear from a person who recovered so completely from a serious brain incident. Her story is not typical of stroke victims; left-brain injuries are more likely to lead to dysfunctions than to blissful peace. But the transcendental is too tightly woven into her narrative to be dismissed and, in her opinion, it is the core of the story’s popularity. Her tale speaks of detachment, energy, transcendence, inner silence and being at one with all things, making people ask themselves, “Do I have all this inside of me, too?”

Fellow scientists did not react en masse. The spark she lit created new possibilities for research, raised skepticism and fired a wide debate. The New York Times reported that Dr. Francine M. Benes, director of the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center, said, “When I saw her on the TED video, at first I thought, ‘Oh my God, is she losing it.'” Dr. Taylor says that most colleagues are warmly supportive, or at least amiably intrigued. Opposition, she says, is rare, but can be vicious. “We scientists label things, but normally do not experience them,” she told Hinduism Today. “In my story, I use two forbidden words, energy and consciousness. There is an idea that, if you are a serious researcher, you can never use these terms.”

Current scientific consensus recognizes her experience, but not her conclusions. Research by Dr. Newman and Dr. D’Aquili (Why God Won’t Go Away, Ballantine, NY, 2001) investigated how mystic experiences stimulate certain areas of the brain. In their experiment, Tibetan meditators and Franciscan nuns in contemplation signaled when they felt connected with God, or the Absolute. SPECT scans of that moment showed a sharp decline in the activity of their left brain while the right hemisphere did not markedly change pace.

But Dr. Taylor’s bravery lies in the assertion that rather than experiencing the “delusion” of God-consciousness, she touched real perceptions of an unexplored facet of reality, one as true as ordinary life–should we only learn to reach it.

She is not comfortable with being called a mystic. To her, she is still a scientist, but also a person who discovered infinite possibilities within herself and everyone else. Hinduism Today asked how her discovery took her to a world well mapped by India’s ancient yogis and gurus. She replied unassumingly, “I don’t know much. I am happy to understand that people have systems that allow them to reach these states of consciousness. I have mine, one that does it for me. But I strongly encourage people to do something that will take them to this precious place inside themselves.”

Helping others reach the heights she touched is still a significant goal. In her TED lecture she calls, “So who are we? We have the power to choose it, moment by moment. I can step into a consciousness where we are the life-force-power of the universe, and of all the 50 trillion beautiful molecules that make up my form. Or I can choose to step into a consciousness where I become a single individual–a solid, separate from the flow, separate from you. Which would you choose? And when?”

In our minds, she believes, lies the foundation for a new, better world–our microcosms transforming the macrocosm. “I believe that the more time we spend choosing the deep, inner-peace circuitry of our right hemispheres, the more peace we will project into the world–and the more peaceful our planet will be.”