Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami had a persistent interest in the Saiva Agamas. The founder of Kauai’s Hindu Monastery, home of Hinduism Today, knew these ancient texts to be the key scriptures defining the Saiva denomination of Hinduism. They are best known today as the source texts for temple construction and worship. But they contain much more, from cosmology and the intricacies of the guru-disciple relationship, to initiations and instructions for meditations on the nature of Lord Siva.

During his lifetime, Gurudeva, as Subramuniyaswami was known, was dismayed that these spiritual texts were virtually unavailable. So, he sent a team of monks on mission in India in the 1980s to discover where these texts could be found in their original palm-leaf manuscript form. Only a few had been put into print. None had been translated into English, or even into Tamil or other Indian languages.

The largest collection of Agamas was encountered at the French Institute of Pondicherry, a hundred miles south of Chennai. This institute was founded and directed by the late Dr. Jean Filliozat, who also directed the nearby French School of the Far East. Dr. Filliozat, wishing to explain the Hindu temple, started the manuscript library soon after opening the institute. During the late 50s and throughout the 60s, the late Pandit N. R. Bhatt spearheaded the collection effort. Bhatt, a scholar of the French School and former head of Indology at the Institute, gathered manuscripts from temples, priests and monasteries across South India.

The Institute now has about 8,600 manuscripts, some as old as three centuries, containing approximately 60,000 texts. Jointly with the French School of the Far East, the total of over 11,000 manuscripts includes the world’s largest assemblage of texts on Hinduism’s Saiva Siddhanta tradition. It has been deemed a UNESCO “Memory of the World” collection. Besides the Saiva scriptures, there are significant numbers of devotional hymns and legends about holy places, Vedic astrology texts, epics, myths and legends, traditional medical texts, Vedas and other literary works. Among the manuscripts, 6,850 are written in Sanskrit in the Grantha script and 1,200 in Tamil.

The palm leaves come in a range of sizes, from the Ramayana Aarudam at just a few inches across to one of the Saiva Agamas at 45 inches long. These leaves, onto which letters are incised with a stylus, can deteriorate quickly in South India’s climate. Many are perforated with holes left by insect larvae. They are so fragile that each handling causes damage; pieces break off, sometimes carrying fragments of writing.

Digitizing the Collection

Gurudeva’s successor, Bodhinatha Veylanswami, visited the Institute in 2005 after learning of the perilous condition of the manuscripts. He intended to protect the Saiva-related material–about half the collection–from further deterioration by having them digitized. But once he understood the significance of the entire collection, which could easily have been ruined by fire, tsunami or other disasters, he offered to digitize everything.

In their day, palm-leaf manuscripts were state-of-the-art technology. Well cared for, they can last for hundreds of years; but if neglected, they can be quickly destroyed by nature. Traditionally, such manuscripts were painstakingly recopied every hundred years or so to preserve them; but that effort stopped in the 19th century. Early efforts to copy the manuscripts using microfilm technology were thwarted by the cost and complexity. Only recently, with the advent of high resolution digital cameras, did an efficient, economical method become available.

The Institute is owned by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Even though the Institute itself had always intended to digitize the collection, getting permission from the French Government to accept Bodhinatha Veylanswami’s offer was a tedious process. Finally, in 2008, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between the Institute and the monastery’s Indian counterpart, the San Marga Trust. The Institute’s new director, Dr. Velayoudom Marimoutou, told us it is quite unusual for the French government to enter into such an agreement with a religious organization.

The entire plan could easily have fallen afoul of the French policy of laicite, their strict version of secularism, or separation of church and state. However, the Institute staff concluded the agreement would not violate the spirit of the policy, since the monastery was covering all expenses, no money was being exchanged and the Institute would own the copyright of all photos taken. Another critical factor was the Institute’s tradition of openness with the collection. It had always allowed any scholar to easily access the manuscripts, unlike many libraries in India which restrict access. Limited access to rare manuscripts is a major obstacle for Sanskrit scholars. The publication of the Institute’s entire collection on-line promises to revolutionize study of these texts by making them available instantly anywhere in the world. Already Dr. S.P. Sabharathnam of Chennai is utilizing the digitized bundles to translate key Agamas into English.

Photographers contacted about the job in the Pondicherry area replied that it would be difficult and technical, requiring years of work and untold American dollars. Unfazed, the monastery sought out institutions with experience in digitization. They soon found the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library at St. John’s University, a Catholic school in central Minnesota. Wayne Torborg, their Director of Digital Collections and Imaging, proved immensely helpful and encouraging. He explained that with mid-price digital cameras and a few meticulous, industrious individuals, the collection could be photographed with top-notch results. He was confident because he was running more than a dozen projects worldwide just like it.

Let the Work Begin

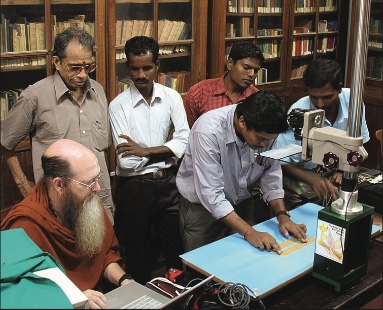

With the MOU secured, plans proceeded in earnest. Experts in ancient manuscripts and photography were consulted, and a simple system using Nikon cameras tethered to Macintosh computers was set up at the Institute. Indivar Sivanathan, a long-time devotee of Gurudeva and professional photographer with extensive archiving experience, helped select and buy the cameras, lenses and copy stands. The project used Nikon D80 and D90 cameras with Nikkor 35mm f2.0 autofocus lenses. Markley Boyer, an expert photographer who participated in Bodhinatha’s 2008 India pilgrimage, volunteered to help set up the project in Pondicherry. Boyer is experienced with Adobe Photoshop, the software used to process the photos.

In December 2008, Bodhinatha and one of his monks set off to India with four Macintosh laptops, four cameras, three copy stands and miscellaneous equipment. They expected to be charged several thousand dollars in duty at Indian Customs in Chennai. But the Customs official quickly shooed the team away to the green lane, insisting, “No duty on cameras and computers”–or possibly no duty for sannyasins.

Four young men were hired to do the work and process the photos. They averaged 2,000 photos daily and completed the collection (save 200 heavily damaged bundles) on January 1, 2011. Altogether, they took 775,261 photographs. These have been assembled into PDF files, one for each bundle, which are available for download on the Institute’s website–possibly the first of India’s ancient manuscript collections to be entirely digitized. The collection is available online at www.ifpindia.org/manuscripts. A second digitization project, nearing completion as of this writing, will preserve 1,600 manuscripts of the French School of the Far East. This is a specialized collection, mostly Vaishnava in content.

Dr. Dominic Goodall of the French School of the Far East warned that the project would “go through cameras.” The D80 and D90 are rated to take 50,000 pictures–more than most people would shoot in years. One of the project’s D80s took 191,695 photos before acting up! In all, the project went through 12 cameras and eight lenses.

In retrospect, the monastery’s project may appear to have been audacious. With no experience in manuscriptology, and only slightly more in photography, they set out to digitize the premier source of ancient Saivite manuscripts. The condition of the manuscripts ranged from excellent to disintegrating. Some would fall apart at the slightest touch; in others, the leaves had become stuck together to form a solid block. A few bundles were found with live worms in them–and this in one of the best-cared-for collections in India. But the final results were excellent, with sharp image clarity.

The importance of these scriptures cannot be overstated. Consider the excerpt at right from Sarvajnanottara Agama, translated by Dr. Sabharathnam. Such profound thought is usually associated only with the Upanishads and Vedanta, the philosophy most well-known in Indian society. Vedanta is even more prominent outside of India, where it is often regarded as the sole expression of Hindu metaphysics. Here, in the Agamas, we find not only such profound expression of Advaitic oneness with God, but an expression melded with the metaphysics of temple worship.

The common Vedantic view regards temple worship as a beginner’s practice, and provides it little philosophic support. Hence, temple worship is left adrift philosophically, especially in the countries of the diaspora, even though temples are the most conspicuous manifestation of Hinduism.

The Adisaivas, Tamil Nadu’s hereditary clan of Sivachariyar temple priests, are the traditional guardians of the Saiva Agamas. It is they who entrusted their precious manuscripts to the Institute. Today, leading Sivachariyar priests–such as Dr. Sabharathnam, Dr. Abhiramasundaram, Dr. K. Pitchai and A.S. Sundaramurthy Sivam–have expressed strong interest in utilizing the priest training schools to produce modern Sanskrit, Tamil and English editions of the Agamas. A meeting is scheduled for July 2011 in Chennai to discuss how to approach this massive endeavor.PIpi

THE LEAVES’ HIDDEN TREASURES

“I am the individual self. Siva who is considered to be the Supreme Self is different from me.” He who contemplates in this way being under the spell of ignorance and infatuation will never attain the exalted qualities of Lord Siva characterized by the power of all knowing and that of all doing. (12)

“Siva is different from me. Actually, I am different from Siva.” The highly refined seeker should avoid such vicious notions of difference. “He who is Siva is indeed Myself.” Let him always contemplate this non-dual union between Siva and himself. (13)

With one-pointed meditation of such non-dual unity one gets himself established within his own Self, always and everywhere. Being established within himself, he directly sees the Lord, who is within every soul and within every object and who presents Himself in all the manifested bodies. There is no doubt about the occurrence of such experience. (14)

Within such a yogi who establishes himself in absolute non-dual union with Lord Siva and who keeps himself free from all sorts of differentiating notions, the exalted power of all-knowing gets unfolded in all its fullness.(15)

He who is declared in all the authentic scriptures as unborn, the creator and controller of the universe, the One who is not associated with a body evolved from maya, the One who is free from the qualities evolved from maya and who is the Self of all, is indeed Myself. There is no doubt about this non-dual union. (16)