T R AV E L O G U E

THE TRAVELS OF TWAIN

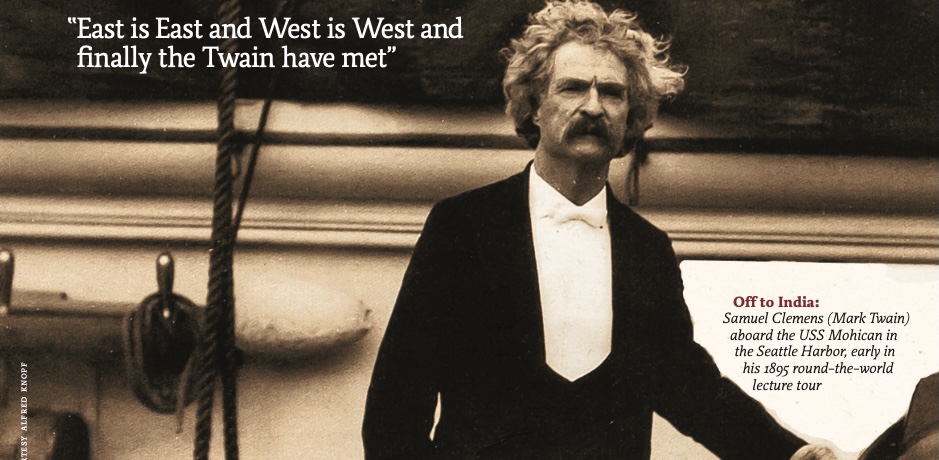

“East is East and West is West and

finally the Twain have met”

Off to India: Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) aboard the USS Mohican in the Seattle Harbor, early in his 1895 round-the-world lecture tour

• • • • • • • • • • • • • •

MARK TWAIN SAID, “I think we never become really and genuinely our entire and honest selves until we are dead—and not then until we have been dead years and years.”

Mark Twain (1835-1910) has now been dead for just over a century, and few would deny that he is looking good for his age. Firmly cemented in history as one of America’s greatest writers, he has been accused of being the funniest man on Earth.

Mark Twain was a printer’s apprentice, a riverboat pilot, a prospector, a Confederate soldier, a newspaper editor, an entrepreneur and a lecturer—and he wrote about it all. It was his writing that made him great—greater still as the test of time now confers on him an immortality he would certainly pooh-pooh.

Although the humor and linguistic genius of Twain’s writing would have earned him enduring celebrity, it was the caustically revealing insight behind all his jesting that made him a legend. There was also the vastness of his subject matter. Extremely well read, well traveled and well informed for a man of his times, he had a little something to say about almost everything. And what he said then could just as validly be said today.

Most certainly, Mark Twain’s fame will not wane. It is, instead, growing like his own tall tales. Ken Burns, Geoffrey C. Ward and Dayton Duncan co-authored a popular and beautifully illustrated biography of him, entitled Mark Twain, companioning a four-hour PBS special that aired in 2002. Hallmark produced a full-length movie entitled “Roughing It” staring James Garner and Jill Eikenberry. Laura Bush, wife of US President George W. Bush, chose Mark Twain as her leading feature author in an American literature series she sponsored at the White House. And for 47 years, in more than 2,000 performances, noted actor Hal Holbrook has traveled the world with his magnificent dramatic monologue “Mark Twain Tonight.” Others are following in his footsteps. The list goes on.

Twain’s tales of his encounter with India and Hinduism are typical of the famous essayist—witty, sagacious, exaggerated and cynical. Yet few people know he ever went to Dharma’s homeland or wrote so extensively about what he saw there.

The journey was not a pilgrimage, though in many ways it became exactly that. At age 60, Mark Twain, whose real name was Samuel Clemens, had fallen on hard times. The literary genius who gave the world Huckleberry Finn, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Innocents Abroad had become a pauper. It happened when he undertook two large business enterprises with Charles Webster Publishing and Paige Typesetting Machine; they both failed miserably. Twain had borrowed heavily for the ventures, and felt personally responsible to investors who had trusted in him.

It was to Twain’s credit that he refused to let those who had trusted in him suffer. He fussed for weeks and finally crafted a plan to recoup their losses doing what he did best—lecturing and writing books. The debt was vast, about $100,000, and so the plan had to be equally ambitious. He chose to circle the globe. It would be a long, arduous journey, and he was sick much of the time, mostly from a cold and a carbuncle. He set sail for the East, traveling west. The itinerary took him to Hawaii, Fiji, Australia, New Zealand, Sri Lanka, India, Mauritius, South Africa and England. It is, interestingly, a list of nations which our late publisher, Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, often traveled to, in the same order.

The Year-Long Adventure

Though he traveled far and experienced much, Twain’s three months in India were the highlight of his year-long trek and the intriguing centerpiece of his revealing 712-page book, Following the Equator.

So it was that the self-proclaimed vagabond and literary gadfly set out on July 15, 1895, to pay his debts; but what he really gave the world was a saga, a romance and a human adventure. Ironically, it was poverty that took him to India and it was poverty-stricken India that made him solvent again—an observation he might have made himself were he not so close to the facts of the matter.

Twain traveled with his wife Olivia and daughter and with a colleague, Mr. Smythe, who made all of the India travel and lecture arrangements. Landing in Bombay from Colombo, he was overwhelmed by the color and the ancientness of the land. He wrote: “This is India! The land of dreams and romance, of fabulous wealth and fabulous poverty, of splendor and rags, of palaces and hovels, of famine and pestilence, of genii and giants and Aladdin lamps, of tigers and elephants, the cobra and the jungle, the country of a hundred nations and a hundred tongues, of a thousand religions and two million gods, cradle of the human race, birthplace of human speech, mother of history, grandmother of legend, great-grandmother of tradition, whose yesterdays bear date with the mouldering antiquities of the rest of the nations—the one sole country under the sun that is endowed with an imperishable interest for alien prate, for lettered and ignorant, wise and fool, rich and poor, bond and free, the one land that all men desire to see, and having seen once, by even a glimpse, would not give that glimpse for all the shows of all the rest of the globe combined. Even now, after a lapse of a year, the delirium of those days in Bombay has not left me, and I hope it never will.”

A trained mind could infer that Mark Twain was impressed with India. But work called. He had chosen a conversational style for his presentations, which he called “At Home.” He thought lectures too formal, too stiff, for his manner and purpose. They were to him “speech,” and he preferred “talk.” That is not to say that Twain’s informal talks, with their long and detailed stories, their tearful pathos and side-hugging fun, were either careless or totally spontaneous. Rather, they were crafted, rehearsed, improved, refined and changed according to each audience. Such a studied approach paid off.

With his white suit, curly hair, shaggy eyebrows and magnetic smile, Clemens’s appearance was compelling. His face did not suggest his latent humor but recalled a stern and serious appearance as he paced up and down the stage, a slender but well-built man in a spotless white suit. Said a Bombay paper, “With his feet planted some distance apart and a hand sometimes in his trouser pockets, elbow sometimes placed against his cheek and supported by the other arm, whilst his eyes, oftener than not, gazed as he would in the presence of a group of familiar friends, he never once raised his voice above a conversational pitch.”

With the help of the press: Mark Twain’s lectures, which he much preferred to refer to as “talks,” were advertised in top Indian newspapers like the Kaiser-I-Hind of Bombay.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Indian audiences, accustomed to British speech, pronunciation and formality, found in his American accent a certain piquancy. They liked it. America was something of a mystery for most people he encountered. They knew about George Washington, about Chicago and its World’s Fair that made Swami Vivekananda a world figure. That was about the extent of general knowledge in those days.

The main purpose for which Clemens traveled around the world was fulfilled satisfactorily, for he collected money enough to pay off a large part of his debt. Much of the success came in India, where his once-in-a-lifetime presence and Smythe’s crafty media hype drew large crowds. Most of the theaters where he appeared accommodated about 1,000 people, and extra seats often had to be provided. In Bombay the Novelty Theatre held 1,400. He collected about US$650 for each evening. Stories, anecdotes, human sketches and homilies, excerpts from Huck Finn and such filled the three-hour evenings. His wife always felt the audience should get its money’s worth and urged him to not end after just an hour or two.

One man wrote: “So, Mark Twain came to India and conquered the people. What the British with nearly a hundred and fifty years of strong rule could not achieve, he could do in one day by being At Home to the people. They had read Mark Twain and were greatly responsive to his subtle humor and highly exaggerated stories.”

An advertisement featured in the Kaiser-I-Hind for a “talk” by Twain.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

The Grand Land of India

Mark Twain had read over much about the subcontinent and imagined its “Aladdin Lamp” atmosphere, but even so he was not prepared for what he encountered between January 18 and March 31, 1896:

“There is only one India! It is the only country that has a monopoly of grand and imposing specialties. When another country has a remarkable thing, it cannot have it all to itself—some other country has a duplicate. But India—that is different. Its marvels are its own; the patents cannot be infringed; imitations are not possible. And think of the size of them, the majesty of them, the weird and outlandish character of most of them!”

“India had the start of the whole world in the beginning of things. She had the first civilization; she had the first accumulation of material wealth; she was populous with deep thinkers and subtle intellects; she had mines, and woods, and a fruitful soul.”

As he traveled through Bombay, Pune, Allahabad, Banares, Calcutta, Darjeeling, Agra, Jaipur, Delhi and other cities, mostly by train (of which he had much to say), the American humorist gathered impressions and crafted them into descriptions. He later wrote about the animals in India, with special reference to the crows and lions and an elephant ride that made him feel quite regal. He gave tales of life in Indian hotels, of fancy parties and long names, of street scenes and fakirs, of the elaborate Indian costumes that made him wax poetic, and even of long-forgotten historical events. An example: “In other countries a long wait at a train station is a dull thing and tedious, but one has no right to have that feeling in India. You have the monster crowd of bejeweled natives, the stir, the bustle, the confusion, the shifting splendors of the costumes—dear me, the delight of it, the charm of it are beyond speech.”

Diaries and notebooks piled up. Of India’s people he wrote, “The bad hearts are there, but I believe that they are in a small, poor minority. One thing is sure: They are much the most interesting people in the world—and the nearest to being incomprehensible. At the very least they are the hardest to account for. Their character and their history, their customs and their religion confront you with riddles at every turn—riddles which are a trifle more perplexing after they are explained than they were before. [As for spirituality], it makes our own religious enthusiasm seem pale and cold.”

QUOTES & QUIPS

BY MARK TWAIN

His first impressions of India

“Everything was absolutely new—all that beautiful color, all those costumes which one hears of but never sees, and which if you see them on stage you never believe in. It defies all description: one simply laughs at the painter’s brush; it is impossible for him to reproduce it.”

His first meeting with a holy man

“Suddenly a man came up who had traveled hundreds of miles for this very experience [of worshiping a holy man]. As soon as he approached near enough, he prostrated himself in the dust and kissed the saint’s foot. I had never realized till then what it was to stand in the presence of a divinity…. I have no hesitation in saying that in all my travels I have never seen anything so remarkable as Banares or anybody so wonderful as that recluse.”

On the poverty of India:

“A feature that has struck me very forcibly in India is the poverty of the country. It is a poverty based upon a certain value which does not exist in the country I come from. Somebody told me that it doesn’t make any difference how low wages in India are, the working man will somehow save something out of it.”

On the city of Banares

“The city of Banares is in effect just a big church, a religious hive, whose every cell is a temple, a shrine or a mosque, and whose every conceivable earthly and heavenly good is procurable under one roof, so to speak…. I think one would not get tired of the bathers, nor their costumes, nor of their ingenuities in getting out of them and into them again without exposing too much bronze, nor of their devotional gesticulations and absorbed bead-tellings.”

From Huckleberry Finn

“You don’t know about me without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer; but that ain’t no matter. That book was made by Mr. Mark Twain, and he told the truth, mainly. There was things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth.”

Following the Equator

In the eyes of the educated Indian people Mark Twain was not merely a public speaker or a writer, but a man with a serious social purpose and human understanding who cemented the hearts of two mutually unknown people with different backgrounds and cultural influences, and subjected to colonial and social tyrannies.

Following the Equator is thought by many to be Mark Twain’s best travelogue, an example of his observations of human dignity and debasement. Travel accounts interested him throughout his life, and he wrote about his trips to Europe and around the American continent. He liked history, biography and travels. He roamed about with an open eye and a receptive mind and told vividly of what he saw. His keen eye detected shams which he exposed with sympathy due to a tolerant attitude about the human condition. His intense interest in social problems and his travel-guide craft reached their height in Following the Equator. Permeated with his uniquely singular stories and whimsies, it received fine reviews during his lifetime. He considered it among his finest efforts.

Mark Twain’s humorous comments are characteristically exaggerated in all his works, but most particularly in his travel accounts. In Following the Equator he starts with a fantastic tale of a shark that swallowed a man and his London Times in England and delivered the paper in just ten days to a shark hunter in Australia who made some money, since the shark-delivered wool market news arrived weeks before the steamer officially docked with the same paper.

Twain was especially impressed with the brilliant color and uncommonness of the Eastern costume. There were many sights of Oriental beauty in India, from “the tender shapely bodies, slim legs and arms and little feet and hands of the Indian woman and the rich and vivid deep colors of the graceful robes they wear—usually silks, soft and flimsy,” to the extraordinarily glittering dress of the maharajahs and princes. It was “all color, bewitching color—everywhere, all around, all the way around.”

There is no doubt that Twain was shaken by the reality he found in India. First in Bombay, then village by village, the immensity of history and of want fell upon his weary eyes. Like a mountain climber, he went through ups and downs of illness and robustness, of gaiety and grief, of distress and wonderment. Any modern-day pilgrim could sympathize with such extremes.

But never did his humor fail him. Encountering the firm Indian pillow in a hotel for the first time, he quipped: “In India from the beginning, in time of war, breastworks have been built of hotel pillows. It was found that a cannon ball could go through earth or sandbag, but when it hit a pillow it hit with a dull thud and dropped to the ground.”

A most sacred place: Banares, located in northeast-central India on the Ganga River southeast of Lucknow, is one of India’s oldest cities. It is a sacred Hindu pilgrimage site with some 1,500 temples, palaces and shrines. This photo was taken around the time that Mark Twain was there. After watching nine corpses being cremated on the bank of the sacred Ganges river in Banares, Twain quipped, “I should not wish to see any more of it unless I might select the parties.”

IN THE CITY OF LIGHT

______________________

Experiencing how Hindus view death

______________________

A TWO-DAY VISIT TO Banares presented Mark Twain and his party with an opportunity to explore Hinduism and investigate especially its contradictions, orthodoxy and superstition. The filthy waters of the Ganga disgusted him, and the fact that pilgrims looked upon it as pure and purifying and drank it eagerly absolutely repelled him.

His enduring fascination with various ways that humankind deal with death and burial was amply fulfilled in Banares. He attended cremation ceremonies for hours on end, watching, stretching his mind to take it all in as he had earlier at the Parsee Towers of Silence. He later wrote, “We are drifting slowly—but hopefully—toward cremation these days. It could not be expected that this progress should be swift, but if it be steady and continuous, even if slow, that will suffice. When cremation becomes the rule, we shall cease to shudder at it; we should shudder at burial if we allowed ourselves to that what goes on in the grave.”

It is truly unfortunate that he was taken around Banares by a good Christian, Rev. Parker, who understood little about Hinduism’s subtle esoterics and profound ways. Twain became victim to one of his own insights, shared in A Tramp Abroad: “Between fools and guidebooks a man could acquire ignorance enough in twenty-four hours in a country like this to last him a year.”

His story of Banares is caustically critical of Hindu beliefs. He noted that wherever there was room for one more Lingam, a Lingam was there. “If Vishnu had foreseen what this town was going to be, he would have called it Idolville or Lingamburg.” Still, he saw so much that was new to him, experienced so fully, that he was to later say, “I think Banares is one of the most wonderful places I have ever seen. It has struck me that a Westerner feels in Banares very much as an Oriental must feel while he is planted down in the middle of London.”

HE LIVED RIGHT NEXT DOOR

______________________

Sharing Common Ground with Mr. Twain

______________________

Mark Twain was here: At the young age of 26, Samuel Clemens hoisted more than a few mugs of beer at the local brewery in Virginia City, Nevada, where he worked as a writer for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise and first came to be known as Mark Twain. A hundred years later that brewery became a monastery (above) where from 1964 to 1972 the staff of Hinduism Today lived, served and founded a major printing press.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

MORE DECADES AGO THAN WE GENERALLY SPEAK OF, the staff of Hinduism Today lived and served in a remote Hindu monastery in the mountain-desert region of Nevada. The wood-and-brick building, standing three stories high, was surrounded by sage in the summer and snow in the winter. It was just half a mile down the hill from Virginia City.

As it happens, Samuel Clemens came to Virginia City with his brother in the summer of 1861. Just 26, he had failed at mining and stock speculations and become a writer for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise. It was here, on February 3, 1863, that “Mark Twain” was born when young Clemens signed a humorous travelogue with that pseudonym.

As it happened, a local brewery served the thirsts of about 70,000 miners (everyone was a miner). Twain visited it often. In case you haven’t guessed, a hundred years later the Old Nevada Brewery became a monastic retreat. We also had occasions to set type for our p.ublications with the same sorts used by Mr. Clemens, in his very office.

Years later, we resettled in Hawaii. But even on the remote Garden Island of Kauai we discovered our rambler had been here first. He noted that our Lumahai Beach (where the movie Bali Hai would later be filmed) was the most beautiful in the world. It is.

And so it was that our destiny and that of the perceptive, comic and bitter Mark Twain crossed—a hundred years apart.

The Oxford of India

Despite the crowded and frequent funereal experiences, Banares was not entirely a disappointment to Mark Twain. He called it “the Oxford of India” for its wealth of Hindu and Sanskrit studies. He met the priests who purported to broker salvation for the pious contributor, but he also met a real holy man in whom Hinduism and saintliness became embodied for him. The man’s name was Swami Bhaskaranand Saraswati. Twain visited the Swami, who had studied Vedanta philosophy and renounced the world, in a small garden called Anandabag where he lived. This soul impressed Twain as a great spiritual leader and scholar, compelling him to write: “He is no longer a part or feature of this world. He is utterly holy, utterly pure.” Their meeting was enthusiastically retold by Twain again and again, “There he is. He is minus the trappings of civilization. He hasn’t a rag on his back. But he has perfect manners, a ready wit and a turn for conversation.”

Tolerance was essential to Samuel Langhorne Clemens. It had to be. He was raised amid its opposite and had seen too much of hatred and self-righteousness in the slave-master relationship of the American South. So he tried again and again to teach others the foolishness of it. After his meeting with the Indian holy man, he reflected at length on the matter: “He has my reverence. And I don’t offer it as a common thing and poor, but as an unusual thing and of value. The ordinary reverence, the reverence defined and explained by the dictionary costs nothing. Reverence for one’s own sacred things—parents, religion, flag, laws, and respect for one’s own beliefs—these are feelings which we cannot even help. They come natural to us; they are involuntary, like breathing. ≠≠There is no personal merit in breathing. But the reverence which is difficult, and which has personal merit in it, is the respect which you pay, without compulsion, to the political or religious attitude of a man whose beliefs are not yours. You can’t revere his gods or his politics, and no one expects you to do that, but you could respect his belief in them if you tried hard enough. But it is very, very difficult; it is next to impossible, and so we hardly ever try. If the man doesn’t believe as we do, we say he is a crank, and that settles it. I mean it does nowadays, because now we can’t burn him.”

Mark Twain eschewed prejudice most of the time, and those that remained with him did not sully seriously his basic conception of man and the world, for he could laugh through them at the stupidities of individuals both at home and abroad. Mr. Bandaranaike, the late Prime Minister of Sri Lanka, appreciated Twain’s “mixture of humorous sympathy for the underdog and moral indignation about the cruelties and hypocrisies of mankind,” adding, “How could I be hostile to a country that produced Mark Twain?”

Nonetheless, Mark Twain never truly comprehended Hinduism. Through Rev. Parker’s eyes he saw the darker side—the unfortunate practices of making religion a business, and the immense poverty (which he rightly blamed on India’s invaders). Only in one visit to a Jain temple did a knowledgeable man present the deeper views and correct a handful of Twain’s misconceptions. But considering himself “a representative-at-large for the human race” more than an American, Twain also saw through the exterior and recognized a serene and self-possessed culture with high principles. In Banares he evinced an inner pleasure at the many men and women kneeling prayerfully for hours “while we in America are robbing and murdering.”

The poverty nearly suffocated him. He blamed the white man who, in the name of civilization and “the white man’s burden,” impoverished many peoples in the world. In his book Mark Twain in India, Keshav Mustalik noted of Twain’s observations: “The white man’s tools were whiskey and wine and tobacco offered with the fetters and hanging pole and noose; the white man’s world was death and murder coupled with the commandment Thou shalt not kill. Mark Twain angrily said, ‘We are obliged to believe that a nation that could look on, unmoved, and see starving or freezing women hanged for stealing twenty-six cents’ worth of food or rags, and boys snatched from their mothers and men from their families and sent to the other side of the world for long terms of years for similar trifling offenses, was a nation to whom the term “civilized” could not in any large way be applied.’ The result of ‘civilization’ was the extermination of the savages: ‘There are many humorous things in the world—among them the white man’s notion that he is less savage than the savages.’”

Being such an avid critic of society, any society, right from the beginning of his literary career, Twain moved forward to a sort of personal study of human life. In India he had anticipated a world of beauty and peace. Indeed, when he landed in Colombo, Sri Lanka, en route to Bombay, his first impression was “Dear me, it is beautiful! A sumptuous tropical, as to character of foliage and opulence of it.” But praise all too soon turned to cynicism when he saw a group of school girls, Sinhalese Christians “Europeanly dressed” and coming out of a missionary school. He thought their clothes ugly, “destitute of taste, destitute of grace, repulsive as a shroud” and preferred aloud the simple, colorful and more natural native garb.

In all, his cynicism of Western society and piety grew deeper as he traveled around the world. He returned to America noticeably disenchanted, a man who wrote his most stinging observations in What is Man? and The Mysterious Stranger. It is all the more remarkable that he wrote cheerfully and with great humor about India and her peoples, that he was able to watch dobies laundering their master’s clothes at the river and inquire: “Are they trying to break those stones with clothes?”

Of India itself he eloquently summed up his three months of exploration: “Nothing has been left undone, either by man or nature, to make India the most extraordinary country that the Sun visits on his round. Nothing seems to have been forgotten, nothing overlooked.”

Toward the end of his journey, tired and full, he wrote a friend, “I have been sick a good deal; the rest not so much. We have had a good time in India—we couldn’t ask for better. There are lovely people here. They made us feel at home.”

Readers who would like to enjoy the entire account of Twain’s Indian experience can do no better than search out the two books below. One is his final product, rich with illustrations, the very book that made it possible to pay off the debtors who inspired the trip in the first place. It is full of stories, wonderful stories, and of observations that are as true today as they were 100 years back.

The second is a short analysis of Twain’s tour, a look behind the scenes. The more ambitious may wish to contact the world’s greatest collection of the man’s life and works: The Mark Twain Papers, which is a full department within the library of the University of California at Berkeley.

REFERENCES:

FOLLOWING THE EQUATOr, 1971, AMS PRESS, INC., NEW YORK, N.Y. , ISBN: 0-404-01577-8, 712 PAGES MARK TWAIN IN INDIA, BY KESHAV MUTALIK, 1978, NOBLE PUBLISHING HOUSE, MUMBAI, 154 PAGES

A REMEDY FOR SIN

Mark Twain knew from extensive reading that India was a place where moral and philosophical subjects were welcome. Since it was his penchant to ponder these matters, he devised a preposterous plan which he presented to Indian audiences whose uncontrollable mirth contrasted with but never shattered the serious demeanor of the man. We share, in brief, Twain’s Moral Regeneration of the Whole Human Race Scheme.

IHAVE GOT A SCHEME FOR THE MORAL regeneration of the human race which I hope I can make effective, but I can’t tell yet. But I know it is planned out upon strictly scientific lines and is up to date in that particular. I propose to do for the moral fabric just what advanced medical art is doing for the physical body. To protect a healthy person forever from smallpox, hydrophobia, diphtheria and so on, the doctor gives him those very diseases—in a harmless form—inoculates him with them—and he’s safe then from ever catching them again. That great idea is going to be carried further and further. Fifty years from now the doctors will be inoculating for every conceivable disease. They will take the healthy baby out of the cradle and punch it and slash it and scarify it and load it up with the whole of the 1,644 diseases (those known to be fearful) that constitute their stock in trade—and that child will be a spectacle to look at. But no matter; it will be sick a couple of weeks, and after that, though it live to be a hundred, it can never be sick again. The chances are that that child will never die at all. In that great day there won’t be any doctors anymore—nothing but inoculators—and here and there a perishing undertaker.

“Now then, I propose to inoculate for Sin. Suppose that every time you commit a transgression, a crime of any kind, you lay up in your heart a memory of the shame you felt when your Sin found you out, and so make it a perpetual reminder and perpetual protection against your ever committing that particular Sin again. That is to say, inoculate yourself forever against that particular Sin. Now what must be the result? Why this—logically and infallibly: that the more crimes you commit (and forever amen) the richer you become, morally; and when you have committed all the trespasses, all the crimes that are known to the calendar of Sin, there you stand, white as an angel, pure as the driven Snow, the sky-kissing monument of moral perfection.

“Now is this a thing difficult? No. There are only 354 Sins possible—that’s all you can commit—that’s all there are; you can’t invent any fresh ones—that’s all been attended to. Now what is 354 Sins? It’s very easy work. It’s nothing—anybody can do it. I know. I have done it myself.”