Reflections on the cultural, religious and social importance found within our moniker

By Keshav Fulbrook

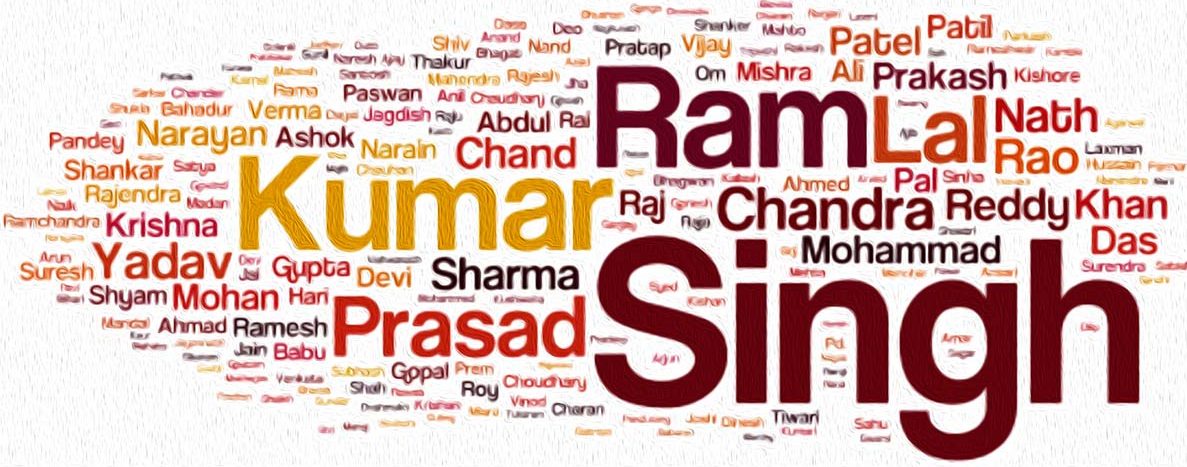

I was 23 when i was given the name Keshav during my namakarana samskara at the Hindu Temple of Las Vegas, my birth town. Many Hindu organizations such as Vishwa Hindu Parishad, the Sangh Pariwar, Arya Samaj and Kauai Adheenam all strongly encourage the adoption of a Hindu name if one was born in a non-Hindu family and seeks formal entrance into Hinduism. Many do not consider an aspirant eligible for diksha or further initiations without this first step. It is a step I took and am glad I did. I am well known by Keshav, especially among the Hindu community. My name is the subject of a lot of questions though, which leads me to reflect on how names are viewed by different people and why.

During my travels in India and Nepal, most people were enthusiastic to know about my interest in Sanatana Dharma which led me to pursue my local study of several Indian languages, as well as Nepalese. Though my experience over all was positive, I was occasionally met with confusion.

In India you will run into many Michaels and Jacobs who converted to Christianity and took Christian names. Similarly, Sikhs, Jains, Muslims and Hindus are all identifiable in India based on name, and if conversion does take place, often it is accompanied with a change in name. Due to the prevalence of this custom in Asia, I had thought that the reason behind a white guy taking a Hindu name would be intuitively understood. However, this is not always the case. To some people, a Hindu name has more to do with being Indian than being part of a trans-national Hinduism. Similarly, at least in the US, many people may not think of a name like Michael in Biblical terms. To them, changing one’s name on adopting or converting to another religion may seem odd.

Unfortunately, a one-way cultural adoption of Western values is often the norm, while the reverse is commonly met with puzzlement. The world wears jeans, but a Westerner in a dhoti will garner stares. Names in particular seem to be associated with a sense of identity in a way more intimate than things like dress, faith, etc. So when one introduces oneself with a name that doesn’t fit someone else’s projection of who a person ought to be, based on our heuristic about them, we almost feel the person is disingenuous.

This reveals to a great degree the power of these projected expectations in shaping behavior, because just a small handful of negative experiences can outweigh a lifetime of positive reinforcement. Thankfully, my personal experience in this area has been overwhelmingly positive, with just a few outlying events.

For every step someone takes down a road less traveled—in which the person finds meaning—the more it clears the way for others in similar shoes. Vamadeva Shastri, Ram Das and countless others have been along this road, as well as less publicly known sadhakas.

All in all, it is about commonplace exposure and numbers. I am definitely far from the first non-hereditary Hindu, but may be the first many have met personally. Most questions are not malicious, but come from genuine curiosity and a desire to connect and understand.

The less spiritually or religiously inclined a person is, the stranger a name change and its motivations will seem to them. I’ve noticed this even among second- or third-generation non-resident Indians—some of whom may themselves have adopted a more Western name. Many seem unaccustomed to a reversal of this. Their question is phrased most often as “What is your real name?” I can only respond, “Keshav is my real name.”

Keshav Fulbrook, 28, is pursuing a political science degree and has been a stalwart member of the Hindu tradition since he was 19. He is currently affiliated with Arsha Vidya Gurukulam. Contact: fulbrookb22@gmail.com