Water holds a special place in every Hindu’s life. The rivers are sacred, the temple tanks bestow blessings, and worshipful offerings are made daily.

By Anuradha Goyal, Delhi

Giving water to the thirsty earns you instant punya or merit—so declared our grandmothers. Travel across India and you see this as a living tradition, where clay pots filled with water are kept on the road for anyone who may be thirsty. With time, clay pots have made way for water coolers, but the idea remains the same. In Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh you still see women sitting on the road in the hot sun to offer water to thirsty passersby. Not just fellow humans; we keep water even for birds and animals.

Water is one of the Pancha Tattva, the five prime elements of which everything is made, four others being Earth, Air, Fire, and Sky. Of these, water is the key nurturer, without which most life, including human life, cannot survive. No wonder, when man decided to settle, he chose to settle near the rivers flowing from hills to the oceans. These lands were fertile, ensuring constant food supply; but more importantly, there was ample water for all kinds of needs. Later, when men did settle away from rivers, they established huge lakes that allowed them to collect water and saturate the earth beneath. Cities like Bhopal, Hyderabad and Bengaluru are a good example of cities full of lakes.

In India, anyone who nurtures you is a Devata, a Deity worthy of worship. So, every source of water is revered and prayed to—be it oceans, rivers, ponds, wells and lakes, or man-made stepwells and temple tanks. Worship of water goes back to Vedic times at least. The Rig Veda’s “Nadi Stuti Sukta” hymn praises the primary rivers that nurtured the land of Bharata, including Ganga, Yamuna, Shutudri (now Sutlej), Sarasvati, Asikni (Chenab), Parushni (Ravi), Vitasta (Jhelum), and several rivers that are lost to us. Most major rivers have their own stutis, or songs, praising them, which are duly sung while worshiping them.

Unfortunately, the water-rich culture that treated water with so much reverence is losing its water at a rapid speed. The rivers are getting polluted with unchecked toxic industrial waste being dumped into them. The region of Cherrapunji and Mawsynram in the hill state of Meghalaya is one of the wettest places on earth, receiving an average of 467 inches of rainfall yearly. Come summer months, even these areas suffer water shortage. Underground water tables are lessening across the country, and are dangerously low in urban areas. Big cities like Bengaluru are predicted to go dry soon. P. Sainath—the founder/editor of PARI (People’s Archive of Rural India) cites per-capita availability of water falling from 5,177 cubic meters in 1951 to 3,300 in 2011. He attributes this to the channelizing of water from small landowning farmers to industries and urban areas.

Dependence on piped water, which consumers have no idea where it comes from, has broken the relationship between humans and sources of water. People whose ancestors started their day by worshiping the water bodies near and far, by invoking all the holy rivers with mantras like “gange cha yamune chaiv godavari sarasvati narmade sindhu kaveri jalesmin sannidhim kuru” as they poured water on their bodies to bathe, now treat it as a commodity like any they buy. Ironically, a people who for eons believed that offering local water to the thirsty carried great merit now sell pilgrims water from the polluting plastic bottles, water that is sucked from the earth and transported long distances. It is time India realizes its sacred relationship with water, revives and re-establishes it, values it, cherishes it, and lives with abundant water, just like our ancestors did.

Abhay Mishra—author and Riverine Culture Scholar at IGNCA, New Delhi, endorses this view that introduction of tap water disconnected us from our sources of water, which used to be collectively managed by society. He recalls their vital role in the family and social rituals and emphasizes that we have forgotten to offer gratitude to sources of water. He talks about the efforts of Saurabh Singh, who is reviving wells for potable water in Ghazipur. It is helping them deal with the grave threat of arsenic in ground water, an issue that has its roots in digging too many tube wells in the fields. He gives an example of Halma, a community effort for common issues, organized by Shivganga organization in the tribal region of Jhabua in central India. Thousands of villagers work one day a week to create 30,000 trenches on the Hathipawa hill to collect rainwater that was otherwise being lost. Each trench is two meters long, one meter wide and half meter deep. Groups of such trenches store and channelize water while improving the biodiversity of the region. All this is achieved through community effort with minimal cost. There are similar initiatives happening in other parts of the country. Hopefully, these water body revival activities will scale up across India and bring back the much-required balance between water management and consumption. These efforts inspire us to look back in time at the great water heritage of India.

Water, Water Everywhere

India is a “Jal Pradhan,” the water-abundant land. It is not only blessed with a 4,670-mile coastline that touches the three oceans, but its whole landscape is adorned with a vast network of rivers originating from hills and mountains and running towards the sea. They are like the nerve system of the country, transporting water, the nectar of life, to all parts of the land. Thousands of mini streams, bejeweled with waterfalls, flow through myriad terrains to join these rivers. India is famously called the land of seven rivers, rivers that are invoked before every major ritual. However, every region has so many rivers and river valley settlements that it would not be inappropriate to call it the land of hundreds of rivers.

Each tributary has famous cities and pilgrimage sites on its banks. Ganga has Haridwar, where it enters the plains at the foothills of the Himalayas, and then Kashi, where it flows northwards for a while looking back at its origin. Cauvery originates from the Kodagu hills in South India and flows eastward towards the Bay of Bengal, nurturing the states of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. Each river has its own stories in the Puranas. King Bhagirath brought Ganga down from the heavens via the hair of Siva. Tapti is the daughter of the sun. The Godavari is called Gautami due to her association with Rishi Gautam. Cauvery came down in the kamandalu, or metal pot, of Rishi Agastya. The Brahmaputra comes from a pond that arose at the place where Brahma’s son was placed, making it a rare male river. According to the Puranas, most rivers are Goddesses who live on Earth in their dravya, or liquid, form. In fact, the most beautiful women in the Indraloka originate from water and are hence called apsaras—ap being water.

India’s reverence for water extends from rivers to every drop of rain bestowed upon its land. In peak summer months, people keep looking at the skies, waiting for clouds to show up and assure them that rains are around the corner. Why not? After all, rains keep the wheels of the agrarian economy moving. Nothing brings more happiness than the abundant rains for four months known as Chaturmas. This is the time when travels are abandoned, fields are left on their own and people stay at home. Even the wandering saints choose one place to stay for these four months. In Ramayana, Sri Ram and his brother Lakshman camped on the outskirts of Kishkindha during Chaturmas before moving to Lanka. The Sanskrit word for monsoons is Varsha. That is the word also used for a year, giving rain the preeminence it deserves. Monsoon is one of the six seasons in India. It usually starts in early June from the southern coast and moves upward, lasting till September. Both cold and hot deserts in Ladakh and Rajasthan get hardly any rain, while coastal regions get about 120 inches, and the wettest parts get as much as 550 inches. Folk songs like “Kajri,” sung during monsoons, are full of emotions that rains invoke. Kalidasa evocatively describes monsoon as a season of longing in his poem “Ritusamhara.”

Anupam Mishra, a pioneer in rainwater harvesting and water conservation, is credited with reviving many traditional water conservation techniques. In his copyright-free book Ponds Are Still Relevant, he takes us through the ecosystem of water bodies in different parts of India. He talks about how people chose the right spot and time to build the pond and how they maintained it over years, involving each segment of the society that benefited from it. Every rooftop was connected to a water collection mechanism leading to individual wells in desert cities, including Jaisalmer, even though it has a wealth of 52 scenic ponds.

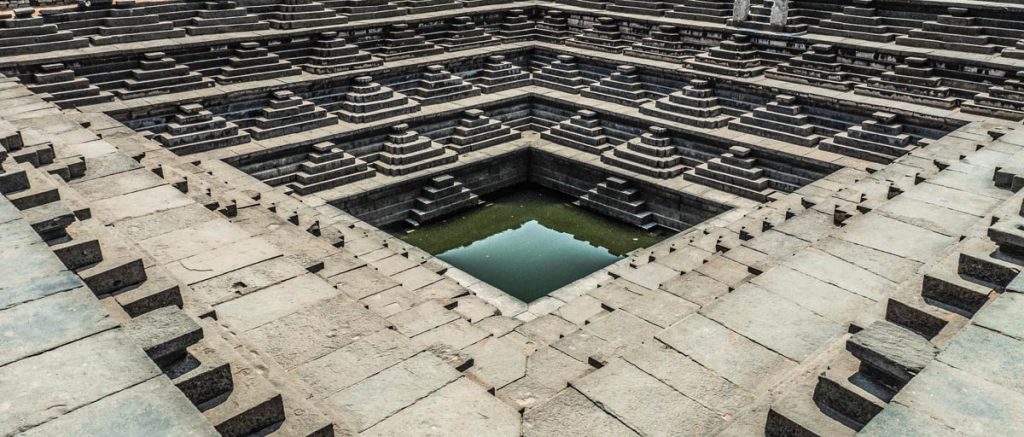

Stepwells

Extraordinary stepwells are sprinkled across the country, more so in the dry western states like Rajasthan and Gujarat. They are man-made oases that not only stored water but served as social places to gather. They are built like inverted temples dedicated to Vishnu, who likes to sleep in the waters of Ksheersagar.

Rani Ki Vav (“Queen’s Well”) was built in the 11th century by Queen Udaymati of Solanki dynasty in the town of Patan in Gujarat state. It descends seven levels below the ground, with stone walls and platforms all around, adorned with ornate carvings, leading to a pool 31 feet square and 75 feet deep. You wonder what inspired the queen to build such an architectural wonder, thought to be a memorial for her departed husband. My answer is punya: the greatest merit that you accumulate is by ensuring water for your people.

At Abhaneri near Jaipur, the sheer symmetry of Chand Baori makes it one of the most photogenic stepwells. Its more than 3,500 rhythmic geometric steps going sideways ensure that you can reach the water level at all times.

At Shringverpur near Prayagraj, there is an ancient elaborate arrangement of connected tanks to collect the floodwaters of Ganga during the rainy season and direct excess water back into the river. The tanks not only collected water but also cleaned it through sedimentation process. We find extensive water management systems in archaeological sites like Dholavira, that belong to the Sindhu Saraswati River Valley civilization, dating back to at least the 8th century bce. Water channels can be seen all around the 2,000-year-old excavated Buddhist caves called Kanheri Caves in the heart of Mumbai. Interconnected water tanks at regular intervals leverage the natural gradient of the rock, capturing water from the roofs of the caves. The water collected in four months lasted for the whole year for the monks.

In the eastern state of Odisha, when you drive through the rural landscape, you know you are close to a village when you see a series of large ponds, invariably with a small temple in the middle or on the banks. In the northeastern states, most ponds are full of lotus flowers that cover the water with their broad leaves, minimizing loss by evaporation.

Each temple in ancient India had at least one temple tank, if not more. Skanda Purana, in its “Ayodhya Mahatmay,” describes a map of Ayodhya defined by a series of interconnected ponds, despite the city being located on the banks of a sarayu, perennial river. In the South, the ancient temple town of Kanchipuram is full of tanks inside and outside the temples. In the heart of the city is Sarv Teertham Kulam, a huge tank surrounded by small temples on three sides. One can only imagine it as a place where the locals and pilgrims mingled and exchanged stories in olden times.

A ray of hope: the revival of temple tanks in Tamil Nadu have yielded immediate impact on the level of groundwater, showing that if the inlets and outlets of these tanks are maintained, they automatically channelize rainwater back into the earth that would otherwise be dissipated.

The best example of water preservation is seen at Mandu, an ancient city located on the top of a tabletop hill with no supply of water except the annual rain. Narmada, the closest river, is more than 40 miles away. The city was among the most densely populated in the world in its time but, it seems, was never short of water. Walk around and you see a series of lakes to collect water. Inside its royal quarters, the buildings are arranged around deep wells to collect every drop of water. You also see luxurious rooftop swimming pools! So much so that its palace is called Jahah Mahal, as it looks like a ship sailing on the water with two huge lakes surrounding it on either side. The whole city is designed around water collection and conservation.

Where Rivers Meet

All the pilgrimages in India involve taking a dip in the holy waters of the place being visited. Can the pilgrimage to Kashi ever be complete without a dip in the Ganga? Famous Panchkroshi Yatra, around the larger mandala of Kashi, begins and ends with a boat ride on the Ganga from Manikarnika Ghat. The highest tribute to the Narmada, the oldest river in India, is Narmada Parikrama, where pilgrims walk the full length of the river and then returning on the opposite bank, taking a holy bath in its water every morning. They walk more than 1,600 miles for months and sometimes years together, stopping for the night at the temples and ashrams and eating whatever they are offered.

That brings me to the grandest celebration of water on Earth, the Kumbh Mela, which happens every 12 years at four different venues. The heart of the massive festival is bathing in sacred rivers—the confluence of rivers Ganga, Yamuna and Saraswati at Prayag; River Ganga at Haridwar; the Kshipra River at Ujjain, and the River Godavari at Nashik. Millions of people travel from across the nation during precise planetary conjunctions just to take a dip in the water. You can do a million things at the Kumbh, but it is essentially a visit to the holy river, to pray to it and to take a dip in it.

Throughout each year there are considered most auspicious to bathe in India’s holy rivers. The full moon night of Karthik, in January, 15 days after the Diwali festival, is celebrated in many ways, but the most important is bathing in a holy river close to you. There also are special snans, or bathing schedules, for intense events like solar eclipses, when pilgrims visit holy sites like Kurukshetra for a ritual bath.

It is interesting to note the purpose said to be served by that each of India’s cardinal dhams. Devatas meditate at the Badrikashram located in the Himalayas in the north.They eat at Anna Kshetra of Puri in the East. They sleep in Dwarka on the western coast. And they bathe at Rameswaram in the South.

There is a water wonder of 22 stone wells inside the premises of Rameswaram temple, where, following ancient tradition, pilgrims take bath after they have bathed the Sivalinga with the Ganga River water they bring from Kashi. They say taking bath in these perennial wells absolves all your sins. Each well has a name and story of kings and sages who took bath in these wells and the type of sin the well is known to affect. For example, at Kodi Teertham, Sri Krishna got rid of the sin of killing Kamsa, and after a dip at Chakra Tirtha the Sun received its golden glow.

In the spirit of giving water to those who need it, India remains a net exporter of water. No, it does not sell its water per se, but its major exports are agricultural products that need a lot of water to grow. Among the primary crops exported are rice, cotton and sugarcane, which are all water-thirsty crops. Add to this the massive meat exports. Essentially India is taking upon itself the water burden of countries it is exporting to. Can it or should it do this while it faces water shortages itself?

It is promising that the Indian Government set up Jal Shakti Ministry in 2019, an agency that looks at water as the key resource and is expected to work on river rejuvenation, including the cleaning of Ganga and on providing safe clean drinking water for everyone. Hopefully, this will bring the focus required to make India water-rich again, along with bringing back the culture that treats water as sacred in everyday life as much as it does in its rituals.

Rameshwaram Temple’s Karma-Conquering Wells

The 22 wells of this ancient South Indian temple wash away pilgrims’ karmas and bestow blessings. The labyrinthine complex is large even by Indian temple standards, with thousands of feet of high-ceilinged granite-pillared corridors. Having pilgrimaged here, you ready yourself by wading out to immerse three times in the Bay of Bengal. You turn and walk 700 feet to the temple tower, entering a fantasy world of stone chambers, slippery floors and steel handrails. At the first well, groups are organized into little tribes that will spend the next 90 minutes together. As instructed by your guru, you hold in your mind the far-too-many wrongdoings of this life—sometimes called sins, but that’s a charged word, too Abrahamic. Your caravansary of misdeeds marches past—the wrongs, the hurts, the transgressions, the vices and victims of your ignorance—all there, carried all this distance. At each well one among them will surge forward, be acknowledged and—as the sacred waters of Sivaness pour over you—washed away and released forever. How it must feel, you wonder, to be free of all that.

The pilgrims are ready, and you are urgently signaled to follow a thin man who scurries ahead holding a dented tin bucket tied to a long, yellow rope. The guide rushes through several dark halls as you and your tribe of 15 try to keep up, confused by the hundreds of other pilgrims following dozens of other bucketeers, all crisscrossing, scurrying barefoot along the wet stone floors, worn smooth by millions of previous pilgrims’ feet. Suddenly the guide stops at the second well and climbs atop the wall with such deftness that you forget how precarious his perch really is. He tosses the bucket into the water some 20 feet below, and with lightning moves born of years of practice, brings the brimming pail up, splashing the cool water with kinetic urgency on the crown of your head. Others step forward for their turn, and you take that moment to purposefully watch one gnarly misdeed disappear.

Off the tribe goes, through a dim tunnel, out into an open, sunny courtyard, then back into the dark corridors, left and right until the third well is reached. You realize you’ve become disoriented in both time and space. That might be a cause for concern, but not here, not now. It is a blissful state, the feeling of being everywhere and everywhen at once.

The wells continue in no logical order, some close, others far. Some are round and others square. One turns out to be the giant temple tank, 100 feet wide and filled with water lilies. You feel the lightness of the soul as felonies, misdemeanors and unkindnesses fall away.

Each well has a story, you are told. The first, Mahalakshmi Tirtham, bestows riches. The second, third and fourth lifted a curse from a rishi. At Ganga Tirtham, the 13th well, Rama was absolved of the sin of killing Ravana. You reach the final well, the twenty-second. Called Kodi Tirtham, it is said to confer blessings equal to bathing in the holy Ganga ten million times. There is no bucket here, just a tiny copper cup holding a few scant ounces. How ironic. The greatest blessings from the smallest demitasse!

You feel strangely different, purer, right with yourself and the world. “How long can this last?” you wonder.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Anuradha Goyal is one of India’s leading travel bloggers. Her key focus at www.IndiTales.com is ancient Indian civilization and temple architecture along with old techniques such as water management with step wells.