From uncounted spiritual poets, we examine the life, language and works of a few

By Lakshmi Chandrashekar Subramanian

Before we speak of the great bhakta poets, we should acknowledge the primary language that was the tool for many of them. Hindi is the treasured national language of India, with 615 million speakers worldwide. Hindu devotees from all regional and language backgrounds engage with Hindi through popular devotional songs (bhajans), scriptures such as Ramcharitmanas (the famed story of Lord Rama), the poems of Kabir, religious stories (katha), and in other ways big and small. Hindi is written in Devanagari script, which it shares with Sanskrit, Marathi, Nepali, Rajasthani, Kashmiri, and dialects such as Brajbhasha and Awadhi which can both be classified linguistically as Hindi. This family of tongues is the medium of a vast body of literature, with every dialect carrying unique nuances.

Brajbhasha, meaning “language of Braj,” was one of North India’s most notable literary languages from the 16th to the early 20th century. Braj is a region in India on both sides of the Yamuna river with its center at Mathura-Vrindavan in Uttar Pradesh state. Brajbhasha was also a major court language, in addition to being the poetic vehicle of many Krishna bhaktas. We refer to a time when there was fluid interweaving between the “devotional” and the “courtly.”

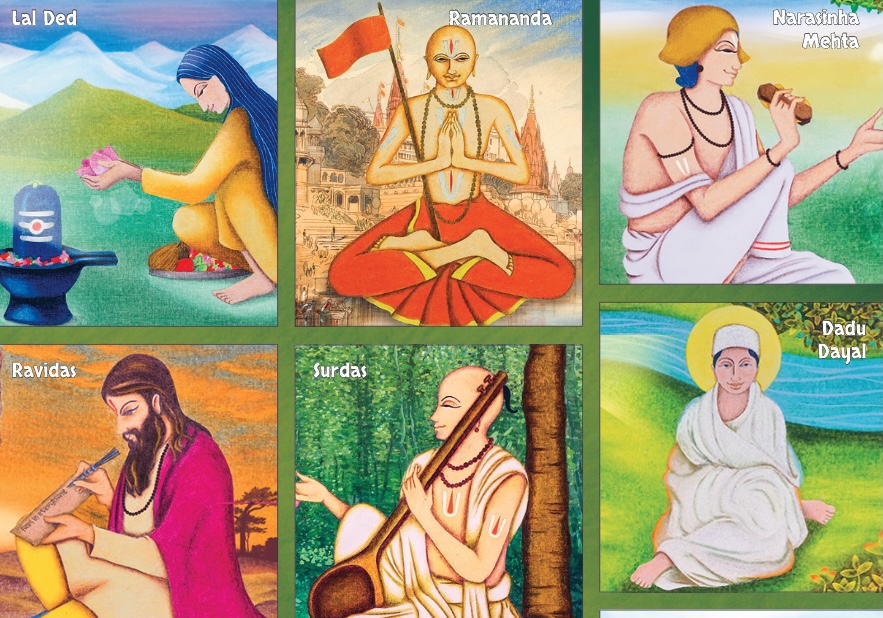

Sanatana Dharma (Hinduism) has given rise to a plethora of poet-saints, immortalized by tradition. Their devotional songs have lived long after their physical passing, carrying on the spirit of their soulful love and longing for God. The seven North Indian saints we are meeting in this Insight—Lal Ded, Swami Ramananda, Narasinha Mehta, Ravidas, Surdas, Dadu Dayal and Tulsidas—sang the universal language of bhakti in five Indian tongues: Kashmiri, Hindi, Gujarati, Brajbhasha and Avadhi. Here we explore a sampling of their works, acknowledging the limits of translating these timeless works into English.

While many of these saints lived in the religious epicenter of Varanasi, they are well-known all over India. Their legacy is not limited to where they hailed from. With the prevalence of Mirabai and Kabir festivals, Amar Chitra Katha comic books, religious cartoons and Hindi serials, these saints have become global religious and cultural icons.

They represent a broad spectrum of bhaktas: from those who sang about the formless Truth, to those with overflowing love for the Divinities Siva, Rama and Krishna. We know little with historical authority, but much from sacred narratives that developed over the centuries. When surveyed together, these reveal consistent legends and themes. Therefore, each poet-saint’s story is cobbled together from narratives, oral and written, popular and historical, drawn from a number of sources.

A genre of poems called “pad” was the favored mode of many of these composers. The closing lines of a pad would provide the author’s oral signature, called “chaap,” an indication to the audience that the poem was about to conclude. Practically, this also creates an inner “wow” as listeners reflect on the poet’s legendary life story, bhakti, and poetic genius all at once. Here we hope to facilitate that inner wow as we dive into the lives, compositions and legends of seven key North Indian saints.

Swami Sivananda queries, “Who is a saint? He who lives in God, or the Eternal, who is free from egoism, likes and dislikes, selfishness, vanity, mine-ness, lust, greed and anger, who is endowed with equal vision, balanced mind, mercy, tolerance, righteousness and cosmic love, and who has divine knowledge, is a saint.” While tradition idolizes numerous saints who lived and breathed bhakti, India has given birth to innumerable more unsung God-intoxicated heroes. It is not surprising that this ancient nation is often referred to as Punyabhumi (“land of merit”), the blessed land where saints could be living anywhere, even in the most unexpected places. The author wishes to honor those saintly souls who have paved the way for a life of spirituality for generations to come.

Lal Ded: Kashmir, c. 1320–1392

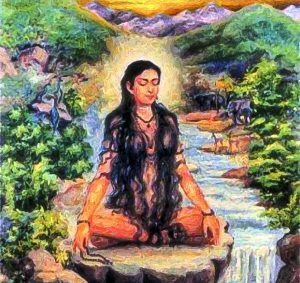

Reminiscent of Akka Mahadevi in 12th-century Karnataka, Lal Ded is a bhakta from Kashmir who dedicated her life to pursue union with Siva. Belonging to the 14th century, a time of political and religious flux, when Kashmir was under various rulers, poet-saint Lal Ded, or Grandmother Lal, known formally as Lalleshwari or affectionately as Lalla (“darling” in Kashmiri), is very much a part of modern Kashmiri psyche due to her mystic poems (vakh) and their universal appeal.

Oral traditions say Lalla was born in Pandrethan, southeast of Srinagar, in the spiritual atmosphere of a traditional Kashmiri Pandit household. Her poems suggest she was educated in Hindu scriptures and yoga philosophy early in life in her father’s home. This is sometimes cited as evidence that girls received advanced education in those times. She was married at a young age and moved to the town of Pampore. It was an untenable marriage, rife with difficulties, and she turned to spiritual life for solace. A popular anecdote goes thus: one day when Lalla returned home late from fetching water at the river (where she worshiped Siva as Natha Keshava Bhairava in a temple on the opposite bank), her mother-in-law accused her of infidelity. Believing this falsehood, her husband grew angry and struck out at her, breaking the pot of water she was carrying on her head. Miraculously, the water remained in the shape of the pot! She then tossed the water into the yard, where it grew into a pond known today as Lalla Trag.

Around the age of 26, Lalla took sannyasa, renouncing the world in search of God Realization. Tradition says she became a disciple of Kashmiri Saiva saint Siddha Srikantha, also called Sed Bayu, a direct descendent in the guru-shishya lineage of Vasugupta, the founder of modern Saivism in Kashmir, a nondualist tradition with scholarly and yogic streams. Lalla lived as a yogini, composing devotional verses on Siva, singing about mystical experiences, ecstatic love for God, seeing Siva in everything, and her nondualistic relationship with God. Kashmiri legends say she shed her clothes and wandered with hair loose, ridiculed by some and worshiped by others. At the end of her life, like Mirabai in the Vaishnavite stream, Lal Ded attained Siva-consciousness and merged into the Divine.

Lal Vakh

Lalla’s succinct, declarative, and at times cryptic, sacred utterances are called Lal Vakh. Over 250 verses have been attributed to her; around 128 are considered indisputably hers. Vakh, singular and plural, is cognate with the Sanskrit vach (speech) and vakya (sentence). Each vakh is usually a stanza of four lines and conveys an independent idea. As one of the earliest compositions in vernacular Kashmiri language, passed down orally through the generations and transcribed many centuries later, Lalla’s verses play a central role in the making of modern Kashmiri language and literature. Today, every Kashmiri native or student of the language would be familiar with her wise utterances, as the language is imbued with them.

Lalla’s proverbs are not easily categorized. They are rooted in Trika Saivite philosophy with Sanskrit phrases, while alluding to ideas from Tantra and Yogachara Buddhism. Lal Ded seems to have been acquainted with Sufism as well. The same vakh can elucidate Hindu philosophy and yogic terminology for one translator, while another envisions her mystic poem through a Sufi lens. Her Lal Vakh have inspired Hindus and Sufis alike, translated differently based on context. Her verses express deep religious yearning, reverence to guru, importance of intense meditation and yogic practices, rejection of orthodoxy and organized religion, and the soul’s burning desire to experience God. They also carry a plethora of images such as moons, lakes, nectar and waterfalls, which sometimes express the celebratory mood of having merged with the Divine within. Among many mystic subjects, she wrote of the power of mantra, as in this verse: “O Lalli! With right knowledge, open your ears and hear how the trees sway to Om Namasivaya, how the wind says Om Namasivaya, how water flows with the sound Namasivaya. The entire universe is singing the name of Siva. O Lalli! Pay a little attention” (The Yoga of Discipline, by Gurumayi Chidvilasananda). In another poem she writes, “I, Lalla, entered the gate of the mind’s garden and saw Siva united with Sakti. I was immersed in the lake of undying bliss. Here, in this lifetime, I’ve been unchained from the wheel of birth and death. What can the world do to me?” (Yong Kian/Wikimedia Commons).

Ambassador of Communal Harmony

Inspiring peace, devotionalism and communal harmony in the Kashmir Valley, Lal Ded’s works represent a confluence of Saivism and Sufism. Her poetry inspired many Sufis of Kashmir over the centuries, and her association with Sufi saint Nund Rishi is especially noteworthy. He formed the Rishi order of saints, who are considered heirs of Lal Ded by some. In a region where Hinduism and Islam have deeply influenced one another, saints like Lal Ded inspire a vision of pluralistic coexistence in how dear she is to both communities. She was revered as Lalleshwari by Kashmiri Hindus and Lalla Arifa by the Muslims.

Lal Ded’s aphoristic sayings are still recited in Kashmir today, making a deep impact on the religion and culture of locals from all walks of life. They have also been adopted by contemporary global movers and shakers in scholarly publications, music, and theater productions. For example, the solo play in Englisççh, Hindi and Kashmiri entitled “Lal Ded” has been performed by actress Mita Vashisht all over India and abroad since 2004.

Testimony from Poet and Author Ranjit Hoskote

“To the outer world, Lal Ded is arguably Kashmir’s best-known spiritual and literary figure; within Kashmir, she has been venerated both by Hindus and Muslims for nearly seven centuries. For most of that period, she has successfully eluded the proprietorial claims of religious monopolists.”

Lal Ded’s Vakh

translated by ranjit hoskote, from his book i, lalla

Kusha grass, flowers, sesame seed, lamp, water:

it’s just another list for someone who’s listened,

really listened, to his teacher. Every day he sinks deeper

into Shambhu, frees himself from the trap

of action and reaction. He will not suffer birth again.

χ χ χ

Who trusts his Master’s word

and controls the mind-horse

with the reins of wisdom,

he shall not die, he shall not be killed.

χ χ χ

The Lord has spread the subtle net of Himself across the world.

See how He gets under your skin, inside your bones?

If you can’t see Him while you’re alive,

don’t expect a special vision once you’re dead.

χ χ χ

Wrapped up in Yourself, You hid from me.

All day I looked for You

and when I found You hiding inside me,

I ran wild, playing now me, now You.

χ χ χ

What the books taught me, I’ve practiced.

What they didn’t teach me, I’ve taught myself.

I’ve gone into the forest and wrestled with the lion.

I didn’t get this far by teaching one thing and doing another.

χ χ χ

Some, who have closed their eyes, are wide awake.

Some, who look out at the world, are fast asleep.

Some who bathe in sacred pools remain dirty.

Some are at home in the world but keep their hands clean.

Learn more

Read the book I, Lalla: The Poems of Lal Ded, translated by Ranjit Hoskote

Listen to Lal Vakh sung on YouTube

Swami Ramananda: Varanasi, c.1400–1470

In Varanasi: With the holy city and Ganges River behind him, Swami Ramananda presses his hands together in worship of Rama and Sita, whom he takes to be the universe entire.

Ram, Ram!” Swami Ramananda is often hailed as the guru of a galaxy of saints—including Kabir, Ravidas, Sena, Pipa and Dhana. He played a crucial role in the cultivation of poet-saints and the propagation of bhakti in late 14th- or early 15th-century North India. As with countless Indian saints, little is known with certainty about his life, but devotees and historians have put together key details. According to Bhagwan Prasad Rupkala, an early 20th-century Ramanandi monk, the saint was born in ancient Prayag as Ramadatta. In his youth, he became a disciple of Raghavananda, who gave him the Ram mantra and initiated him as Ramananda. According to legend, as a youth Ramananda went on pilgrimage to South India and returned as a follower of Sri Vaishnavism in the line of the renowned philosopher-theologian Ramanujacharya, though he disagreed with that tradition’s strict ritualistic guidelines and caste exclusivity. Some Ramanandis, such as Rupkala, disassociate their founder from the South Indian Vaishnavas. Another influence in Ramananda’s teachings is that of the Nathpanthi ascetics.

After his travels, Ramananda settled in Varanasi, on the banks of River Ganga, to preach in local dialects his liberal ideas of egalitarianism, selfless devotion, and making bhakti truly accessible to all people.

A famous story details Swami Ramananda inadvertently initiating weaver-saint Kabir on the banks of the Ganga in Varanasi. While walking up the ghat steps one morning, he tripped over Kabir who lay prone on the step, waiting for Ramananda. As he stumbled, Ramananda exclaimed the name of the Lord, “Ram!” Kabir took that as his sought-after initiation. From then on, Kabir, like his guru, sang the glories of the Lord. In another version, Kabir goes to meet Ramananda and requests initiation. The guru initially sends him away; but later, once convinced of Kabir’s sincerity and wisdom, he initiates the persistent seeker. Scholars over past decades have questioned the historicity of this relationship due to the conflicting dates attributed to the two poets, but Ramanandis and Kabir Panthis retell the story often, valuing it as an important puzzle piece in their enigmatic biographies. Stories narrate that another poet-saint, Ravidas, a leatherworker of Varanasi, also received his spiritual mantra from Ramananda, while other versions say that Ravidas’s guru may have been Kabir. In any case, several of the well-known North Indian bhakti saints are considered spiritual descendants of Swami Ramananda.

The Ramananda Tradition Today

A pioneering force of bhakti in North India, Saint Ramananda is also the inspiration behind the Ramananda Sampradaya, an ascetic Hindu order. Its sadhus (saint-practitioners), often called Ramanandis or Vairagis, adhere to vows, discipline and austerities. They are considered the largest monastic order in North India, the parent of numerous subgroups. Ramanandis who choose to get initiated in additional vows of austerity become Tyagis (renunciates), and Mahatyagis, undertaking even more stringent vows. Disciplines include restrictions in food, clothing and lifestyle choices. With bhakti as the core of all Ramanandi practice, two ways of interacting with the Divine emerged: one that savored “saguna” (God with form) worship towards Lord Rama and His consort Goddess Sita, and the other “nirguna” (formless Divine), deeming Rama as the ineffable supreme Reality. Poet-saint Tulsidas extolled the saguna philosophy with his Shri Ramcharitmanas, a devotional text at the heart of the Ramananda tradition, while Kabir was a leading voice of devotion to the formless divine with his dohas and bhajans (couplets and songs). Today, Ramanandis live throughout western and northern India, predominantly in the states of Gujarat, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, the Ganges basin, the Himalayan foothills and Nepal.

Testimony from Dr. Ramdas Lamb

“Swami Ramananda opened up Ram bhakti to the masses like no one else. During my time as a vairagi in India, it was always so refreshing to be in satsang with those for whom devotion was both the means and the goal, the process as well as the product. Swami Ramananda played a pivotal role in the individualization and personalization of the bhakti tradition. One of the sayings commonly heard within his order with respect to who is qualified to follow the path is Jati pati puchha na koi. Jo Hari ko bhajan, so Hari ka hoi. He taught anyone who had an interest in learning the path of devotion, including females and males, Hindus and non-Hindus, those of any caste, rich and poor, educated and uneducated. Living at a time when Sanskrit was considered by many as the religious language, he encouraged his followers to sing, write and teach in vernacular languages that listeners could understand and relate to. Undoubtedly, his best-known direct disciple was Kabir, and by far the best known of the members of his lineage is Tulsidas. For both, love of God transcends all limitations (jati pati).

“In the contemporary world, far too many seek to emphasize our differences with each other, whether it be caste, class, ethnicity, ideology, physical appearance or ability. However, those differences are so temporary and thus so meaningless. For Ramananda, and ideally for all his followers, Ram and Sita together are the essence and the manifestation of all reality. Thus, seeing and serving that Universal Divinity in all should be the ultimate goal for all of us. Tulsidas presents this idea and approach to life in the two verses from his manas (presented in the sidebar at right).”

Did You Know?

Guru and God are both highly regarded in Hinduism. Ramananda’s fame spread due to his illustrious disciples, especially poet-saint Kabir. A popular couplet of Kabir, translated by Linda Hess, goes thus:

Guru and God are before me. Whose feet should I touch?

I offer myself to the guru who showed me God.

Learn more

Discover Ramanandi practices in “Monastic Vows and the Ramananda Sampraday” by Dr. Ramdas Lamb, scholar and former Ramanandi Sadhu, in the book Dealing with Deities: The Ritual Vow in South Asia

Read Vasudha Paramasivan’s PhD dissertation, “Between Text and Sect: Early Nineteenth Century Shifts in the Theology of Ram”

Listen to Musical renditions of Ramananda’s “Ek Onkar” on YouTube

Swami Ramananda’s Shabad

in the Adi Granth

translated by sant singh khalsa

One Universal Creator God. By the Grace of the True Guru.

Where should I go? My home is filled with bliss.

My consciousness does not go out wandering.

My mind has become crippled.

One day, a desire welled up in my mind.

I ground up sandalwood, along with several fragrant oils.

I went to God’s place, and worshiped Him there.

That God showed me the Guru, within my own mind.

Wherever I go, I find water and stones.

You are totally pervading and permeating in all.

I have searched through all the Vedas and the Puranas.

I would go there, only if the Lord were not here.

I am a sacrifice to You, O my True Guru.

You have cut through all my confusion and doubt. Ramanand’s Lord and Master is the All-pervading Lord God. The Word of the Guru’s Shabad eradicates

the karma of millions of past actions.

Verses from Tulsidas’s Manas

translated by dr. ramdas lamb

Knowing the universe is filled with Sita and Ram,

I join my hands bowing to them in pranam.

[Lord Ram exclaims:]

Hanuman, he is my devotee who is pure in the thought

Of seeing me, his Lord, in all that moves and does not.

Narasinha Mehta: Gujarat, c.1414—1481

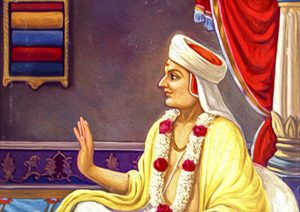

Can you name the poet-saint whose hymns were a moral compass for visionaries such as Mahatma Gandhi? That is none other than 15th-century Narasinha Mehta of Gujarat, also known as Narsi Bhagat. Honored as Adi Kavi (“first poet”) of the Gujarati language, Narasinha is both a renowned literary figure and a beloved Vaishnava saint whose devotional songs about Krishna are widely sung in Gujarat, Rajasthan and beyond.

Narasinha was born into a Saivite Nagar Brahmin family who worshiped Lord Siva. Legends say he lost his parents at a young age. He later married and had two children. He lived with his brother and his wife in the city of Junagadh. Narratives portray his becoming a Vaishnava thus: Narasinha was so engrossed in singing bhakti songs that he did not earn enough, which his sister-in-law taunted him about. In indignation and search for peace, Narasinha Mehta took refuge in a forest, where he meditated in an abandoned Siva temple for seven days and nights without food or water. This prompted Siva to appear and offer him a boon. Narasinha was so overwhelmed he couldn’t think of what to ask for. On impulse, he asked for what was rare to the Lord Himself. Siva transported him to Lord Krishna’s world of Raas Leela. Seeing Krishna and the Gopis’ devotion transformed Narasinha, and he was filled with Vaishnava bhakti—all through the grace of Siva.

Narasinha Mehta unites Saivite and Vaishnavite communities with his affiliation to both traditions. He also bridges the nirguna and saguna communities. His poems, written in a genre called pad, show that he was well-versed in the Vaishnava cannon, and was influenced by Vedantic philosophy and classical Sanskrit kavya literature. Passed down orally, his songs extol nirguna bhakti (devotion to the formless Divine), Sri Krishna Leela (Krishna’s divine play), reverence to Siva, and moral teachings. Many of these are sung as early morning hymns (prabhatiya in Gujarati) in temples and at night-long bhajan gatherings in Gujarat. Some poems share glimpses of his life, including miracles and his encounters with the Divine.

Narasinha Mehta and Gandhi

As seen in the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Narasinha Mehta is one of the saints whom Gandhi glorified in his writings, along with Tulsidas, Surdas, Mirabai and Kabir. Narasinha and Gandhi both hailed from Gujarat and believed in an egalitarian society. Like Gandhi, Narasinha interacted with people from all castes. This angered and alienated his own community, but did not stop him from living the ideals he preached. Gandhi was born in a Vaishnava family, and there came a point in his life when Narasinha’s bhajan “Vaishnava Jana” struck a deep chord. In fact, it was in the context of this song that Gandhi defined himself as a Vaishnava. Gandhi said even his Christian and Muslim friends loved the song, as it espouses ethical guidelines that transcend religious affiliations.

Professor Neelima Shukla-Bhatt discusses this in her 2014 book: “The references to Narasinha in Gandhi’s writing indicate that the saint-poet’s songs formed an integral part of Gandhi’s inner world and that the saint’s sacred biography, with its marked stress on voluntary poverty and empathy for the downtrodden, offered him a model to emulate as well as to invoke in public life. Gandhi also found in these songs and narratives valuable resources to support his social and political ideology. He adopted the term Harijan (children of God) from a Narasinha song to refer to the Dalits, the “untouchables” of Hindu society, and recurrently alluded to the saint in public debates about untouchability in Gujarat.”

Universal Moral Anthem

Narasinha Mehta’s iconic song on moral values begins with Vaishnavajana to tene re kahie (Call only that one a true Vaishnava), and encourages peace and noble thought, word and action (see sidebar, right). Set to raga Mishra Khamaj by Pandit Narayan Khare, the song outlines the virtues of a truly spiritual person, worthy of emulation (termed Vaishnava in the bhajan). As Gandhi’s favorite, it became a part of his ashram’s book of bhajans despite having no political or patriotic undertones. It was sung in daily prayer meetings and important public events such as the 1930 Salt March. As a core part of the Gandhian Movement, it appealed not only to Gujarati speakers but united all Indians, and humankind at large. It is taught to children at Gandhi Camps even today. The song is reminiscent of Kanchi Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswati’s “Maitreem Bhajata,” a benediction in Sanskrit encouraging world peace and harmony composed for the United Nations. Similarly, Narasinha’s “Vaishnava Jana” functions as a universal moral anthem that warms the heart of anyone who cherishes compassion, empathy, truthfulness and devotion.

Every top musician in India, whether vocalist or instrumentalist, has performed this song. Some of the most soulful renditions include those of M.S. Subbulakshmi and Lata Mangeshkar. The Narasinha tradition gained momentum with Mahatma Gandhi’s inspired use of his songs and life story, and continues to evolve as younger generations give his eternal poems their own innovative layers of meaning.

Did You Know?

Narasinha Mehta No Choro, in Junagadh, Gujarat, is the place where the poet-saint and his followers gathered for spiritual discourses and bhajans. Narasinha is believed to have had his first darshan of Lord Krishna in this sacred spot.

Rupayatan, a school of Gujarati art and literature in Junagadh, together with an artists’ association called Gujarat Kala Pratishthan, has undertaken a creative project to document Narasinha’s inspiring poetry in visual art.

Learn more

Read the book Narasinha Mehta of Gujarat: A Legacy of Bhakti in Songs and Stories by Neelima Shukla-Bhatt

Enjoy many renditions of “Vaishnava Jana” on YouTube

Watch Hindi devotional biopic “Narsi Bhagat” (1940) by Vijay Bhatt

Narasinha Mehta’s Pads

translated by neelima shukla-bhatt

Call only that one a true Vaishnava

who understands others’ pain,

who helps them in their suffering,

but has no arrogance in his heart.

The one who respects everyone in the world

and speaks ill of none,

who is unwavering in speech, action and thought,

blessed, blessed is his mother!

The one who sees everyone as equal, and has given up desires,

who views another’s wife as mother,

whose tongue does not lie,

who does not touch another’s wealth,

who is not bound by illusory attachments,

whose detachment is firm,

and whose heart is immersed in Ram’s name,

all places of pilgrimage are within his body.

The one who is without greed or deceit,

who has subdued anger and lust,

on seeing that one, says Narasaiyo:

seventy-one generations are saved.

χ χ χ

Meditate on him.

Contemplate on him.

The Lord is in the eyes;

the singular focus of search within.

He will be seen in your body, will touch you with love—

the unique, unmatched, unheld form.

With your heart filled with joy and karmas destroyed,

the earth will appear like the woods of Vraj.

Krishna will sport in the lovely bowers;

the young woman and her friends will watch him with joy.

Ravidas: Varanasi, c. 1450–1520

Let’s transport ourselves to Varanasi, one of India’s religious epicenters (also known as Benares and Kashi), on the banks of River Ganga in Uttar Pradesh. Here, in the 15th or 16th century in the southern village of Sri Govardhanpur, lived a devoted leather worker (chamar) called Ravidas. He composed powerful, soulful devotional hymns in Hindi, earning a noteworthy place in the family of North Indian bhakti poets. Ravidas mentions poet-saints Namdev, Trilochan and Kabir in his compositions, indicating deep solidarity with them.

One of the distinguishing features of the devotional works often highlighted from this period was their voice-giving to the lower classes. Ravidas, sometimes known as Raidas, often sang of his status as a shoemaker, demonstrating that such livelihoods are in no way a barrier to reaching God. In fact, his trade offered a unique vantage point for him to transcend social distinctions through bhakti. He exclaims in one of his couplets, “O, well-born of Benares, I too am born well known: my labor is with leather. But my heart can boast the Lord” (translated by John Stratton Hawley and Mark Juergensmeyer).

Like poet-saint Kabir, also from Varanasi and famous for his nirguna bhakti, Ravidas often sang about devotion to the formless Divine and is thought by many to be a disciple of Saint Ramananda. Nirguna literally means without qualities, making nirguna bhakti seem like an oxymoron. How can one feel love towards something without qualities or personality traits? Herein lies the genius of Ravidas. Unlike Mirabai or Surdas, who gained spiritual fulfillment by loving and surrendering to God in a specific form, Ravidas ardently communicated his love for Divinity without form. Ravidas uses Ram as a synonym for God or Truth, and as a goal that one should meditate on and strive towards.

Ravidas as Mirabai’s Guru

In the late 17th century, Anantadas dedicated an entire section of his hagiographies to Sant Ravidas, called the Raidas Parchai. Here we read of several miraculous incidents demonstrating the purity of Ravidas’s devotion. Moreover, we find stories about Ravidas’s meeting with the Rajput queen Jhali of Chittor, who is presumably Mirabai, the iconic poet-saint from Rajasthan (as per Ravidas Ramayana). Anantadas describes Queen Jhali’s search for a guru and how she went to Ravidas in Varanasi for spiritual guidance. He writes that the queen bowed down and touched her forehead to his feet. Subsequently she received initiation from him. There is mention of Brahmins objecting vehemently to the initiation, but they did not prevent it. Queen Jhali then returned to her royal palace, after donating money to Ravidas’s temple, which the saint used to feed the poor. There is also mention of Queen Jhali’s sending a letter to Ravidas, requesting him to visit Chittor. After gaining permission from “his big brother” Kabir, Ravidas leaves for the city. This episode in Anantadas’s hagiography is a prime reason for the popular belief that Ravidas was Mirabai’s guru.

Ravidas in the Dadu Panth

Several of Ravidas’s poems are embedded in the scriptures of the Dadu Panth, a sect headquartered in Rajasthan. Dadu’s followers revere Ravidas as one of the four great bhaktas, following his teachings alongside those of their guru, Dadu Dayal. Legend has it that Ravidas met Nanak, the founder and first guru of the Sikh tradition, at the Guru Bagh (Gurus’ Garden) in Varanasi. Philosophically, Ravidas, Dadu Dayal and Guru Nanak share a spiritual affinity to poet-saint Kabir (c. 1398-1448) and his teachings. All three considered themselves to be in Kabir’s lineage. The poems of all four of these saints carry common themes, such as challenging caste distinctions and the authority of organized religion. Inspired by the ascetic teachings of the Nath Yogis, each spurned external forms of worship and encouraged turning inward to seek God and wholeheartedly loving God. Over time, Ravidas’s charismatic hymns gained so much momentum that they were included in various Hindu and Sikh scriptures. Indeed, much of his poetry was adopted into the Sikh scriptural anthology Adi Granth.

In Recent Times

In 2001, the Indian government issued stamps in Ravidas’s honor to celebrate his birth anniversary. Considered by many as their guru, the saint continues to draw thousands of followers from Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, who visit the Sant Ravidas Janam Asthan Mandir to offer prayers on his birth anniversary each year. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Ram Nath Kovind paid a visit there in February 2019.

Ravidas inspires India’s youth to this day. For example, the Saint Shiromani Ravidas Youth Club in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, organizes activities to promote the philosophy of the poet-saint, as well as that of Dr. Ambedkar, and assists needy youth financially and otherwise, something the impoverished poet might have done himself.

Did You Know?

Numerous temples, religious organizations and educational institutions worldwide draw inspiration from the life and works of Ravidas. Many community leaders in North India adopt his philosophy of helping others in their service to their community.

The Amar Chitra Katha comic book series was launched in the 1960s with the goal of teaching Indian children about their rich cultural heritage. The series featured legendary stories of famous North Indian saints, including Ravidas, Surdas, Tulsidas, Kabir and Mirabai. These richly illustrated booklets were often a child’s first introduction to the saints, whose poetry they might learn as part of their school curriculum. The comics are still widely available, on Amazon and elsewhere.

Learn more

Visit Sant Ravidas Janam Asthan Mandir in Seer Goverdhanpur, Varanasi, India

Listen to Ravidas’s famous bhajan “Prabhuji Tum Chandan Hum Pani” on YouTube

Ravidas’s Poems from the Adi Granth

translated by john stratton hawley & mark juergensmeyer

A family that has a true follower of the Lord

Is neither high caste nor low caste, lordly or poor.

The world will know it by its fragrance.

Priests or merchants, laborers or warriors, halfbreeds,

outcasts, and those who tend cremation fires—

their hearts are all the same.

He who becomes pure through love of the Lord

exalts himself and his family as well.

Thanks be to his village, thanks to his home,

thanks to that pure family, each and every one,

For he’s drunk with the essence of the liquid of life

and he pours away all the poisons.

No one equals someone so pure and devoted—

not priests, not heroes, not parasoled kings.

As the lotus leaf floats above the water, Ravidas says,

so he flowers above the world of his birth.

χ χ χ

The day it comes, it goes;

whatever you do, nothing stays firm.

The group goes, and I go;

the going is long, and death is overhead.

What! Are you sleeping? Wake up, fool,

wake to the world you took to be true.

The one who gave you life daily feeds you, clothes you;

inside every body, he runs the store.

So keep to your prayers, abandon “me” and “mine,”

now’s the time to nurture the name that’s in the heart.

Life has slipped away. No one’s left on the road,

and in each direction, the evening dark has come.

Madman, says Ravidas, here’s the cause of it all—

it’s only a house of tricks. Ignore the world.

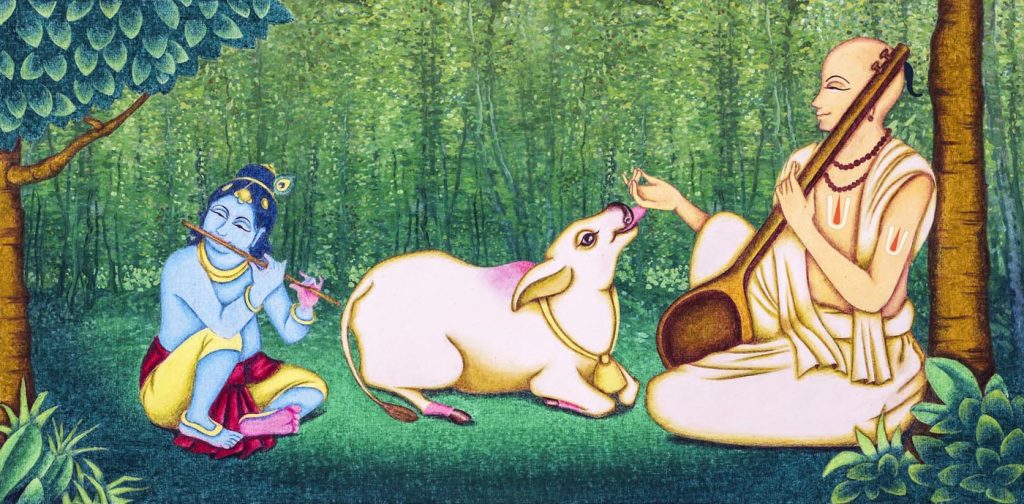

Surdas: Braj, c. 1478—1584

What poet, hearing the poems Sur has made, will not nod his head in pleasure?” asks 17th-century saint Nabhadas in Shribhaktamal, one of the oldest Indian vernacular hagiographies. This is bhakti scholar John Stratton Hawley’s translation of the opening line on Surdas, expressing appreciation for the saint’s poetic brilliance that is shared by countless devotees worldwide.

Surdas is a mainstay in the family of North Indian bhakti saints. Primarily a saguna poet, he composed in Brajbhasha for and about a personal God with personality traits (saguna: sa “with,” guna “attributes”). To Surdas, Divinity came in the form of Shri Krishna, the eighth avatar of Vishnu. Surdas also wrote about Lord Rama and Sita, and often addressed Hari; but he is most celebrated for his songs on Krishna leela (“divine play”).

Surdas is remembered as a blind poet-saint in the Braj region south of Delhi, where Lord Krishna spent his childhood. There are many explanations for Sur’s loss of sight, ranging from blindness from birth, to metaphorical blindness, to his request to Krishna to remove his vision after a magnificent darshan of the Lord. Devotees consider his blindness an advantage, as worldly distractions would not affect his spiritual vision. The songster was renowned in his own times in the 16th century. Stories include his being invited to compose for Mughal emperor Akbar, who greatly admired his poetry. Nabhadas, who composed his influential Shribhaktamal in the early 1600s, devoted several lines praising Surdas’s matchless lyrical dexterity in conveying the depths of devotion. Since then, Surdas has remained renowned among Vaishnava poets, revered by worshipers and scholars alike.

Surdas is the most well known of the ashtachaap, “eight seals,” or eight great disciples, of the Vallabha Sampradaya, also known as Pushtimarga. Founded by Vaishnava philosopher-theologian Vallabhacharya (c. 1475–1530), this devotional community engages in pure nondualism (Shuddha Advaita) through Krishna-centric worship. One of Vallabhacharya’s grandsons, Gokulnath, compiled the Chaurasi Vaishnavan ki Varta (Accounts of Eighty-Four Vaishnavas) in the 17th century. The work features Surdas as a principal teacher in the tradition and contains an account of his life, with Vallabhacharya as his spiritual mentor.

Sur’s Ocean of Poems

The massive poetic corpus Sursagar (“Sur’s Ocean”) recounts numerous episodes from the tenth canto of the Sanskrit Bhagavata Purana in literary Brajbhasha dialect. According to the Vallabha Sampradaya, Surdas composed 125,000 poems, some of which are in the Sursagar, with others having been lost over time. Historians date the earliest manuscript of Sur’s poems at 1582, with 239 poems, from Fatehpur in present-day Rajasthan. By 1640, Sur’s collection of poems was termed Sursagar and contained 795 poems. That number steadily increased in later manuscripts, with a 19th-century Sursagar containing nearly ten thousand. Academicians conclude that poets over the centuries adopted Surdas’s voice and wrote poems in his name, even including his signature (chaap). Some poems in the Sursagar are about him; others simply embody his inspiring devotion. Surdas’s authorial identity extends thus beyond his lifetime, and the Sursagar now refers to the collective poems of the evolving Sur genre. As devotees, we can ask ourselves: If a poem can evoke bhakti in our hearts and minds, how much does history’s academic stamp of approval on the poet’s identity really matter?

Themes Surdas Loved

Surdas’s poems are lyrically par excellence, replete with visual detail describing darling Krishna’s divine deeds, virtues and form, often as elaborated in the Bhagavata Purana, using such terms as “dark one” and “Nanda’s delight” for Krishna. These are not mere creative descriptions but translations of affectionate addresses traditionally associated with the Lord.

Typical of bhakti poetry, Surdas’s poems emphasize personal experience and emotional engagement in relational terms, such as maternal affection (vatsalya bhava) for baby Krishna, or lovers’ honeyed emotions (madhurya bhava). The language frequently demonstrates viraha vedana, the longing and agony of separation from the divine beloved Hari. Surdas assumes the persona of a devotee, male or female, and at times even that of Lord Krishna. The gopis (cowherding women) whose ultimate goal is spiritual union with Krishna, epitomize viraha.

Surdas is also famous for bhramargit, “songs to the bee,” a type of viraha poem that the gopis of Braj sing to Krishna’s messenger Udho. While Udho consoles and philosophically reasons that Krishna exists within them as Supreme Being of the nirguna persuasion, the gopis respond by lauding the greatness of devotion to Lord Krishna with personality traits. Not surprisingly, a major theme in Surdas’s poetry is humble supplication, vinaya poetry that demonstrates a devotee’s laments and complaints of having been deserted or ignored by their Lord. The Sur genre continues to evolve today as artists and devotees recreate and relive his poems in temples, homes and concert halls worldwide.

Did You Know?

Like his female counterpart Mirabai, Surdas is a truly pan-Indian poet-saint. Though he is from the Braj region, his soulful compositions to Krishna and inspiring life story are famous in every Indian state. Vaishnava communities (those who regard Maha Vishnu and His avatars as Supreme) globally adore his bhakti-laden poetry.

Krishna leela, or divine play, as described in the Hindu scripture Srimad Bhagavatam, is full of colorful stories, from childhood antics to adolescent pranks. Surdas’s poems vividly capture every incident with emotional sensitivity and poetic flair. Another famed bhakta who composed poetry on Krishna with similar expertise is the 18th century Tamil composer-saint Oothukadu Venkata Kavi.

Learn more

Read John Stratton Hawley’s book Surdas: Poet, Singer, Saint

Listen to singer Anup Jalota’s “Main Nahin Makhan Khayo” bhajan on YouTube

Enjoy Sursagar paintings online and in museums around the world

Surdas’s Poems

translated by john stratton hawley

A Bhramargit from 1582 in Fatehpur

Having seen Hari’s face, our eyes are opened wide.

Forgetting to blink, our pupils are naked

like those who are clad with the sky.

They’ve shaved their Brahmin braids—their in-laws’ teachings,

burned up the sacred thread of decorum,

And left their veils—their homes—to mumble exposed

through the forests, day and night, down the roads

In simple concentration—their ascetic’s death;

beauty makes them vow their eyes will never waver,

And anyone who tries to hinder them—husbands,

cousins, fathers—fails.

So Udho, though your words touch our hearts

and we understand them all, says Sur,

What are we to do? Our eyes are fixed.

They refuse to be moved by what we say.

χ χ χ

Ever since your name has entered Hari’s ear

It’s been “Radha, O Radha,” an infinite mantra,

a formula chanted to a secret string of beads.

Nightly he sits by the Jumna, in a grove

far from his friends and his happiness and home.

He yearns for you. He has turned into a yogi:

constantly wakeful, whatever the hour.

Sometimes he spreads himself a bed of tender leaves;

sometimes he recites your treasurehouse of fames;

Sometimes he pledges silence; he closes his eyes

and meditates on every pleasure of your frame—

His eyes the invocation, his heart the oblation,

his mutterings the food to feed

the priests who tend the fire.

So has Syam’s whole body wasted away.

Says Sur, let him see you. Fulfill his desire.

Dadu Dayal: Rajasthan, c. 1544–1603

A spiritual lighthouse claimed as their own by two Indian states, Dadu Dayal was a gifted poet who was born in Ahmedabad, Gujarat and spent his spiritual life in Rajasthan. Affectionately known as “compassionate (dayal) brother (dadu),” he attracted both Hindus and Muslims with his nonsectarian teachings.

Some say Dadu was a foster son of a wealthy businessman in Ahmedabad named Lodhiram, who found the baby floating on the Sabarmati River in 1545. In his childhood, Dadu was blessed by an elderly sage named Vriddhananda, or Baba Budha, whom Dadu’s followers revere as God Himself. Having received divine instruction from Baba, Dadu commenced worshiping the peerless Absolute Brahman.

Considered a disciple in the lineage of saints Ramananda and Kabir, Dadu was a cotton carder (dhuniya or pinjari) by occupation, who married and had four children. After some years, he left family life and became a religious wanderer, finally settling down in Rajasthan. There he garnered a large following, which marked the formation of a sect called the Dadu Panth. Some accounts suggest he once met the Mughal emperor Akbar in the famed city of Fatehpur Sikri.

Nirguna Poetry

The Dadu sect reveres the Divine as the formless (nirgun), untainted Existence-Consciousness-Bliss (Sat-Chit-Ananda). Historically, the nirguna sant tradition flourished in several parts of North India, particularly Punjab. This strain of bhakti advocates devotion to the ineffable Absolute, without shape or form. Like the renowned 15th-century poet-saint Kabir, Dadu Dayal was known for his influential nirguna compositions. His “Dadu Anubhav Vani” is a compilation of 5,000 verses (padas) on such topics as truth, virtue and faith, documented by his disciple Rajjab. Composed in the Brajbhasha dialect, they exalt spontaneous bliss (sahaja). The themes of Dadu’s poetry echo those in Kabir’s poems, as well as motifs used by earlier Sahajiya Buddhists and Natha yogis. In one doha, called “Kaya Mahai Rati Dina,” Dadu sang: “The breath is the single-stringed musical instrument that continually emerges and subsides within one’s body. Dadu says, ‘When I found the supreme guru, he made me become one with the primordial sound of God within.’”

Equality of all was a pillar of Dadu’s teachings. He preached that devotion to God should transcend religious or sectarian affiliation, and that devotees should become non-sectarian, or nipakh. He promoted japa (repeating names of God) as a tool for turning inward to find God, and stressed the centrality of guru, a source of divine authority who can lead the aspirant to God. Dadu’s followers venerate other sants alongside their guru, including Kabir, Namdev, Ravidas and Haridas, all of whose poems feature prominently in the Dadu Panth scripture Panchavani.

Shedding His Mortal Coil

Dadu spent the last phase of his ascetic life in Naraina, near Jaipur in Rajasthan, where he attained mahasamadhi in 1603 at age 59. Subsequently, his body was taken in a palanquin from Naraina to Bhairana, where popular legend says Tila, a disciple, saw him standing at the entrance of a hilltop cave where he declared, “Satya Ram,” and disappeared into the cave. Dadu Panthis say that on the palanquin, in place of his body, only flowers remained, which they then offered into the final cremation fires. Today, the site of the vision is called Shri Dadu Palkan. Here the religious sect offers free accommodation to pilgrims, along with lunch and dinner prasad.

The Dadu Dwara in Naraina, the main center of worship for Dadu Panthis, is a sacred place of asceticism, as well as an education center and hub of religious discourse. Naraina is home to many of Dadu’s followers.

The Dadu Panth

The sect Dadu founded remains a vibrant spiritual community to this day. It consists of male and female monastics, as well as householder devotees. They abstain from alcohol and are vegetarian, in line with the ascetic character of the tradition. The Dadu Panth is headquartered in Rajasthan, where it first originated, and its scriptural texts serve as a major resource for early manuscripts of poems by Dadu and other north Indian saints, such as Ravidas. By traditional accounts, Dadu had 100 disciples who attained samadhi. He instructed 52 disciples to build ashrams, known as thambas, of which the five most sacred are in the cities of Naraina, Bhairana, Sambhar, Amer, and Karadala (Kalyanpura). These are places of pilgrimage for devotees from Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra and other parts of the country. The lineage is continued through a succession of acharyas who carry on Dadu Dayal’s vision as spiritual heads. All of them worship their Compassionate Brother with utmost love.

Testimony from Rajesh Anand, Singapore

Only with devotion to God and guru we can transcend the maya and reach the divine realm where is there is no birth, death, disease, old age, etc. That is a state of complete bliss. This can only be achieved in human form. Bhagavad Gita and other scriptures state this unequivocally. Poet saint Dadu Dayal says the same in his poetry: “Human form, which is rare, is not [easily] obtained again and again; this human birth is a priceless gift granted by the grace of God.”

Did You Know?

Dadu Dayal had such great respect for Kabir that Dadu’s followers preserved Kabir’s poetry in their collections. Thus we find that the Dadu Panth scriptures are a wonderful resource, capturing the 15th-century poet-saint’s writings.

Learn more

Spend a day at the Mandir Shri Dadu Dwara in Jaipur, Rajasthan

Listen to Dadu Dayal bhajans on YouTube

Read books and essays about Dadu Dayal by Winand M. Callewaert

Dadu Dayal’s Padas

translated by w.g. orr

The Creator has many and diverse names:

Choose the name that comes to mind;

thus do all the saints practice remembrance.

The Lord who endowed us with soul

and body—worship Him in your heart;

Worship Him by that name

which best suits the moment.

χ χ χ

Where Rama is, there I am not; where I am, there Rama is not.

This mansion is of delicate construction; there is no place for two.

While self remains, so long will there be a second;

When this selfhood is blotted out, then there is no other.

When I am not, there is but One; when I obtrude, then two.

When the veil of “I” is taken away, then does the One become as It was.

χ χ χ

Ah me! Oft do I feel such pangs of separation from

my Beloved that I am likely to die unless I see Him.

Maiden, hearken to the tale of my agony;

I am restless without my Beloved.

In my yearning desire for the Beloved I break into song

day and night; I pour out my woes like the nightingale.

Ah me! Who will bring me to my Beloved?

Who will show me His path and console my heart?

Dadu says: O Lord, let me see Thy face,

even for a moment, and be blessed.

Tulsidas: Varanasi, c. 1543–1623

In the Hanuman Chalisa, poet-saint Tulsidas seeks the grace of Lord Rama, Sita, Lakshmana and Hanuman, fervently requesting them to forever reside in his heart. This hugely popular 40-verse ode is today memorized and chanted by devotees worldwide. Hanuman is known to help not only human beings in need, but is so loyal and powerful that his service extends to even the Gods! Tulsidas describes this and more in his composition, at the heart of which is beloved Hanuman’s virtues, valor and surrender to Rama. Like Hanuman, poet-saint Tulsidas devoted his life to Shri Rama bhakti; in his case, by creating and reveling in literary masterpieces on Lord Rama and Hanuman.

A proponent of Rama Nama (repeating the Lord Rama’s name) and one of India’s most renowned Hindi devotional poets, Goswami Tulsidas was a Sanskrit scholar, bhakta and saint who lived in 16th-century Varanasi during the Mughal rule of Akbar and Jahangir. Tulsidas composed many devotional hymns, including Sankat Mochan (glorifying Hanuman as “Remover of Sorrows”) and Vinaya Patrika (“Letter of Humble Petition” to Rama). His most celebrated work is Shri Ramcharitmanas, the Ramayana epic recomposed in the eastern Hindi dialect, Avadhi. Stories about Tulsidas record his interactions with his bhakti kin, poet-saints Surdas and Mirabai.

Transformation from Grihasta to Bhakta

An anecdote from Priyadas’s early 18th-century hagiography Bhaktirasabodhini revolves around Tulsidas’s transformation from a grihasta (householder) to bhakta (devotee). Rambola and Ratnavali are names popularly attributed to Tulsidas and his wife. Rambola utterly adored Ratnavali. Once, upon returning from a trip and realizing that she had gone to her parents’ home (a common custom for young brides), he rushed to be with her. Amar Chitra Katha comics portray him using a corpse as a raft to cross a river, and mistaking a snake for a rope while climbing up to her window. Once he and his wife were face to face, she was so stunned by his intense dedication to her that Ratnavali reminds him of the impermanence of earthly love. She explains that while the body is a temporary reality of bones covered with skin, the love of Rama lives on forever. Shocked to the core upon hearing such wisdom from his wife, Rambola sets out on the path to Truth. He leaves his young family and dedicates his life to God. Years later, having lived the life of a bhakta, constantly craving a vision of Lord Rama, he composes the Ramcharitmanas as Saint Tulsidas.

The Masterpiece: Shri Ramcharitmanas

One of India’s greatest treasures, the Ramayana was composed by Sage Valmiki in Sanskrit around the 5th to 4th century bce, as estimated by historians. It is a magnificent epic narrating the life of the divine king Rama, which over time has been many an artist’s creative playground. It manifests in diverse textual versions, oral recreations, classical and folk singing, temple rituals and recitations, theatrical shows, and pravachanas (discourses) in which one learns the philosophical nuances of Rama’s dharmic example. In all of these, retelling, enacting and reflecting are common factors. Add to this a trove of visual art, architecture, sculpture and popular media portrayals it has inspired. There are Ramayanas in numerous South and Southeast Asian languages, as scholar A.K. Ramanujan points out: Balinese, Bengali, Cambodian, Chinese, Gujarati, Javanese, Kannada, Kashmiri, Laotian, Malay, Marathi, Oriya, Prakrit, Sinhalese, Tamil, Telugu, Thai, Tibetan—as well as Jain and Buddhist tellings. In Sanskrit alone, there are more than 25 versions in various genres. With one central storyline, we enjoy a multitude of discourses based on each poet’s vision, audience and context.

Tulsidas brought this epic of Rama into the Hindi language. One cannot reflect on the life of Tulsidas without dipping into his awe-inspiring Manas (Spiritual Lake). Shri Ramcharitmanas (roughly translating to “The Spiritual Lake of Rama’s Acts”) is a Hindi version of the Ramayana about Lord Rama’s life and great deeds from the bhakti perspective of Tulsidas, composed in the latter half of the 16th century. Scholars suggest it was influenced by Kambar’s 12th-century Tamil Ramayana, called Ramavataram.

A fascinating feature in Tulsidas’s Ramcharitmanas is the deep reverence that Siva (the presiding Deity of Varanasi) and Rama have for one another. While Siva extols the greatness of Lord Rama, Rama is a worshiper of Siva. In other poetic works, Tulsidas praises Rama and Siva in every other line, as he equates Siva’s greatest mantra, Namasivaya, to Rama’s name. Saint Tulsidas thus served as a bridge between two major Hindu streams.

Through his epic poem, Tulsidas made Lord Rama’s story accessible in Avadhi. In those days it was not customary to render such works in a local dialect. Despite being challenged by many at the time, Tulsidas thus expanded the reach of the epic boundlessly. This can be likened to making devotional works available in numerous transliterations and translations in the 21st century, enabling seekers worldwide to reflect on India’s spiritual wisdom regardless of language.

Did You Know?

During the Dussehra festival, the “Ramlila of Ramnagar” (Varanasi) is performed every evening for 31 days, during the course of which the entire Ramcharitmanas is recited. Each scene is elaborately enacted in a different part of the city. The Ramlila is a spiritual and visual treat for attendees as they follow and witness the story of Rama.

Learn more

Visit the Tulsi Ghat neighborhood, as well as Sankat Mochan Hanuman Temple and Tulsi Manas Mandir in Varanasi

Read Philip Lutgendorf’s book The Life of a Text: Performing the Ramcaritmanas of Tulsidas

Listen to renditions of the Hanuman Chalisa on YouTube

Poems from the Vinaya Patrika

translated by john stratton hawley

and mark juergensmeyer

The name of King Ram: think of it with love.

It is provisions for those who journey empty-handed,

and a friend for those who travel alone,

It is blessedness for the unblessed,

good character for those with none,

A patron to purchase goods from the poor,

and a benefactor to the abandoned.

It is a good family for those without one,

they say—and the scriptures agree—

It is, to the crippled, hands and feet,

and to the blind it is sight.

It is parents to those who are destitute,

solid ground to the ungrounded,

A bridge that spans the sea of existence

and the cause of the essence of joy.

Ram’s name has no equal—

Rescuer of the fallen:

The thought of it makes fertile earth

from Tulsi’s barren soil.

χ χ χ

To those who look to Hanuman

The fulfillment of promises is certain,

like a diamond-cut line in stone.

He makes the impossible possible, the possible impossible—

no one else receives such praise.

Those who think on Him, that joyful treasure,

are freed from adversities and cares.

He is favored by the Gods—Parvati, Siva,

Lakshman, Ram and Sita—

And Tulsi; the gracious gaze from that monkey

is a mine of good fortune, a mother lode.