Illuminating the pivotal role of ancient Hindu temples in the preservation of South India’s history encapsulated by chronicles carved in stone

By Sunitha Madhavan, Chennai

For those who value knowledge of the ancient past, temples built by the Imperial Cholas are historical treasure troves. Their inscriptions impart knowledge of the forgotten past, revealing the culture and history of this mighty dynasty which dominated South India and much of Southeast Asia. The heights of the Cholas’ achievements took place between the 10th and 13th centuries ce. Many gems of knowledge await us from the precepts of the great Chola rulers.

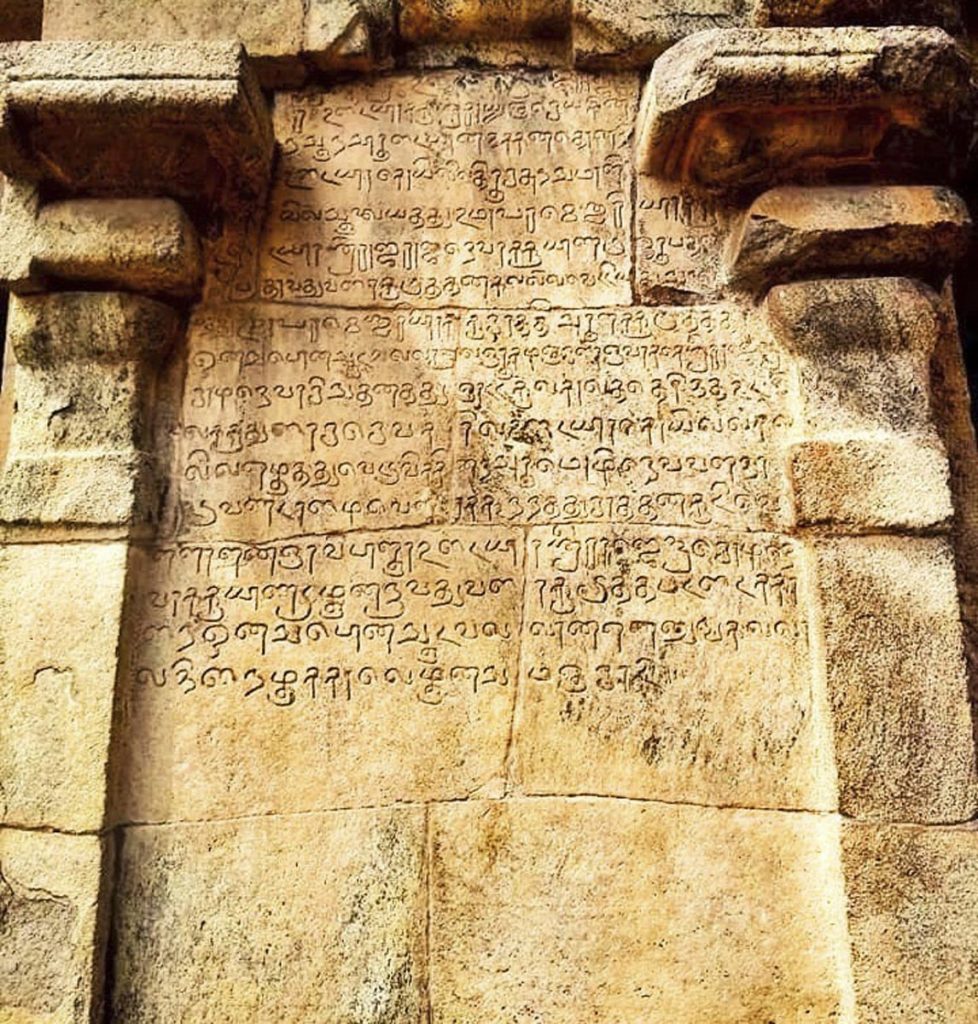

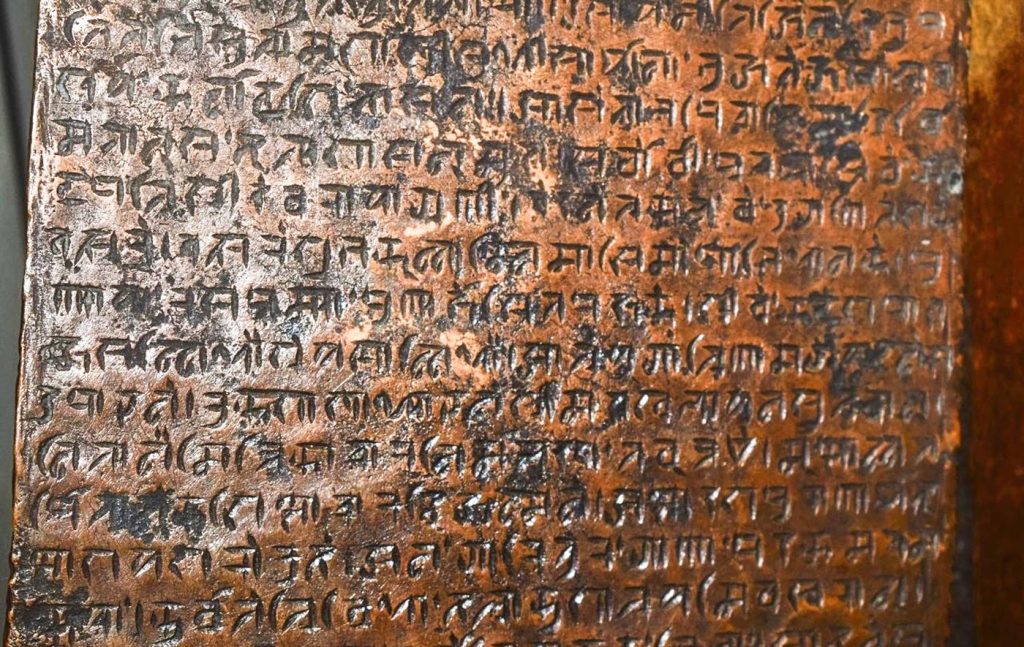

A stone temple is a bastion of information from the time it was created and from the people who constructed it. Throughout South India, not only do we find information in a structure’s architecture or in the geological makeup of its stones. Here we find countless inscriptions, missives from the past, that can be dated to a period, era or regnal year of a monarch. So, too, do we find metallic records, the copper-plate charters known as thambara sasanas—notifications, frequently official in character, concerning proclamations or endowments. Temple inscriptions on imperishable materials like stone and metal were intended as lasting records, not subject to revisions or interpolations. Early granite temples were replete with such inscriptions. Some of them even had in their custody the copper plate grants that documented endowments made for their upkeep. Epigraphy, the science of deciphering such inscriptions, is the primary tool for historians to study the past, which impacts our present and future.

Discovering the Past

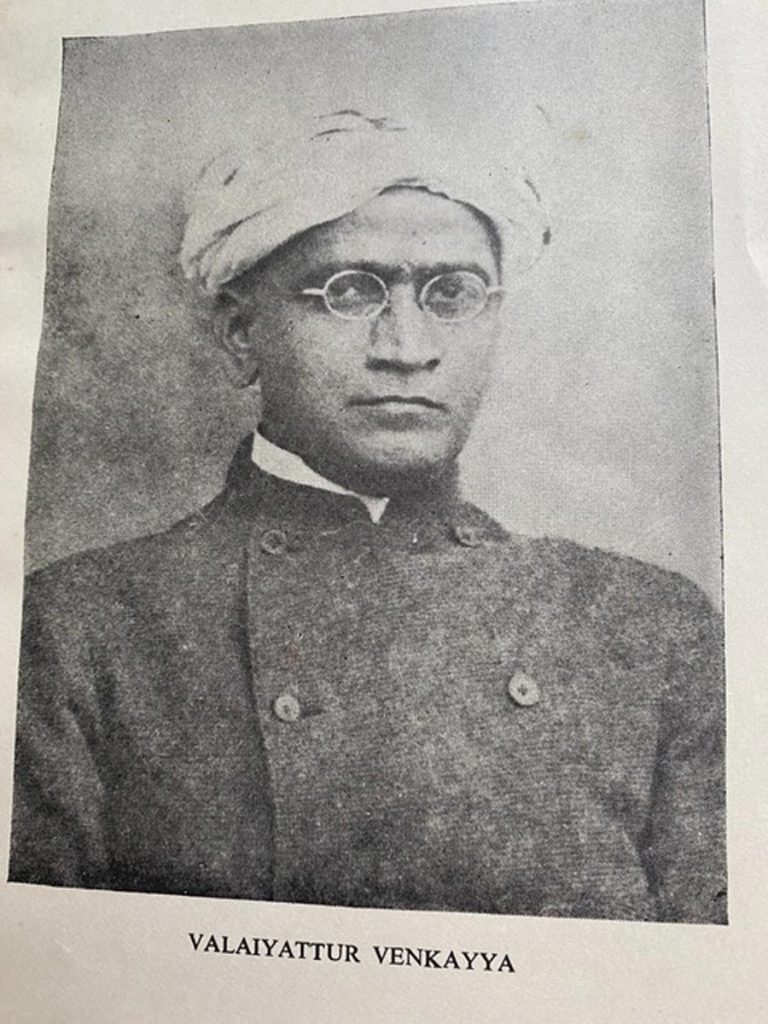

Rai Bahadur V. Venkayya was the first Indian epigraphist, historian and Chief Epigraphist to the Government of India. In 1906 he discovered a string of 31 copper plates weighing over 200 pounds, issued by King Rajendra Chola I, from the Vataranyesvara Temple in Thiruvalangadu village near Madras. These furnished the genealogy of the medieval Cholas starting from King Vijayalaya (middle 9th century ce), who wrested Thanjavur from the Mutharaiyars. His son Aditya Chola I vanquished the Pallavas of Kanchi, initiating the reign of Imperial Cholas. These inscriptions have provided much of what we know of the history of the dynasty.

Interesting nuggets of information from Chola temple inscriptions pepper the account on their judicious administration. They built not only magnificent temples but also irrigation tanks for their agrarian economy to prosper. How well they were all managed is known from the inscriptions. The select highlights presented here relate chiefly to three prominent monarchs of the age, Parantaka Chola I (the son of Aditya I) Rajaraja Chola I (the great grandson of Parantaka I) and Rajendra Chola I (the son of Rajaraja Chola I).

The Pallavas, the predecessors to the Cholas, built rock hewn temples. Tamil readers of Kalki Krishnamurthi’s historic novel Sivagamiyin Sabatham would be familiar with the monolithic constructions at Mamallapuram. Structured granite temples were the forte of the Cholas, who came later. The crest jewel among them is the stone structure at Thanjavur—Brihadishvara Temple, built by Rajaraja Chola I. The historical fiction of Kalki Krishnamurthi’s magnum opus, Ponniyin Selvan, pivoted on the bewildering court intrigues of Rajaraja Chola I, prior to his enthronement.

The era’s true history is authenticated by epigraphical evidences. The Pallavas reigned supreme in South India between 600-900ce. Thereafter, the Chola hegemony prevailed. The heritage of the Pallava empire was kept up by the Cholas in temple architecture, administration and political systems. A temple built by one dynasty may be expanded or renovated by subsequent ruling monarchs, who leave their mark on it. The Kailasanathar Temple at Kanchipuram, originally constructed by Rajasimha Pallava (Narasimha II), contains inscriptions of both Pallava and Chola periods. We are informed it was Parantaka Chola I who covered the roof of the Siva temple at Chidambaram with gold at Vyagragraha—the Sanskrit name for Puliyur, the “tiger village”—in Tamil parlance. This bears reference to Chidambaram temple, where legend has it that Vyagrapada, a sage with tiger’s feet, worshiped Lord Siva.

In Awe of Ancient Governance

Undisputed masters of stonecraft, the Cholas also excelled in statecraft. Near Kanchipuram is the hamlet Uthiramerur, where a group of temples were built by Nandivarma Pallava. Of exceptional interest are inscriptions in Grantha script, Tamil language, of Parantaka Chola-I (907-955ce) discovered there by V. Venkayya in 1898 at Vaikuntha Perumal Temple and on the walls of the Grama

Sabha Mandapa of Sundara Varadaraja Temple. They register rules made by Parantaka Chola I for the proper management of village committees. The two most famous of these inscriptions were brought forward and published in 1889. During his 12th regnal year, Parantaka sent an officer to Uthiramerur with instructions that rules be framed for good governance. Laxity resulted in mismanagement of funds. Two years later, the emperor—though engrossed in expanding the empire—was paying equal attention to local administration. He sent another letter calling for stringent regulations to correct the mismanagement. The village assembly heeded the royal request, and soon the problem was resolved. It must be noted that the emperor could not impose the decision. Only when the residents agreed would it take effect. The Cholas had perfected a highly organized system of central control which simultaneously fostered village autonomy, recognizing each village as a little republic.

Once deciphered, Uthiramerur’s inscriptions wowed Westerners and awed scholars. In ancient times village administration was honed to a perfect system through elections. Though the Chola records are unique in the density of inscriptions elaborating their system of self-governance, inscriptions of the Pallavas and Pandyas also suggest the norm of self-governance for village life. In this millennium, when Bhumi Puja, ground blessing, was performed in December 2020 for India’s new Parliament building, Prime Minister Modi lauded these inscriptions as a standing testimonial to the democratic character of the land from earliest times.

The second inscription of Parantaka I provides great detail on the method of electing the village government. It states that the arrangement was “for the prosperity of our village in order that wicked men may perish, and the rest may prosper.” The settlement concludes: “Thus from this year onwards, as long as the sun and the moon endure, committees shall always be appointed by pot-tickets alone.”

The engraved constitution of Uthiramerur reveals that the village was divided into 30 wards. The village assembly (governing body) consisted of committees—the Tank Committee, Garden Committee and Annual Committee for general supervision. These had 6, 12 and 12 members respectively—30 representatives in all, one drawn from each ward. The eligible members were nominated by the resident villagers from every ward.

Purity in public life was held on a high pedestal. The qualifications for candidacy included age (35-70), education (knowledge of dharma in scriptures), property (residential house built on their own land, paying taxes) and conduct (acquired property through honest means). Disqualifications were also specified. Tenure of office was one year, and anyone who had served on any committee in the previous year was disallowed; the office could be held only by rotation. Those who had failed to submit accounts while in prior service were debarred from ever holding office again. If anyone had embezzled communal funds and defaulted, they, along with their family and friends, were debarred for seven generations. Thus, each village functioned as a nursery of virtue. The Sage of Kanchi, who lived for a 100 glorious years, had spoke on the sublimity of the Uthiramerur inscriptions in Deivathin Kural, The Voice of God.

Secret ballot by pot-tickets was used for choosing committee members. A kudam (pot) was the ballot box; the ballots bearing the candidates’ names were palm leaves. The ballots for each ward were packeted separately. The 30 packets were put in a pot. On the day of election, all villagers had to be present. The priests also assembled. The eldest among them lifted the pot containing the 30 packets. The contents were placed in an empty pot and shaken well. A little boy then drew one ballot from the pot and gave it to the official arbitrator, who received it with open palm and announced the name of the winning candidate from that ward. This procedure was repeated for each ward. The 30 men were thus chosen for the three committees. But if a member was found guilty of any offense while in office, he was fired at once and could never again hold office.

The inscriptions furnish incontestable proof of the exalted representative form of rural government in ancient times. Vincent A. Smith, in his book The Early History of India, remarks: “It is a pity that the apparently excellent system of local self-government, really popular in origin, should have died out ages ago. Modern governments would be happier if they could command equally effective local agency.”

The village assembly managed internal affairs—collecting taxes, making payments, maintaining charitable institutions and the village temple, performing works of public utility, and overseeing cultivation of land and irrigation needs. The inscriptions also suggest judicial function. The legendary report of the Madras Epigraphist demonstrates how the village community functioned effectively and efficiently in the realms of social, political, economic and religious life.

Valuing Temples

Parantaka Chola I gold gilded the roof of the Golden Hall of the dancing Siva at Chidambaram. His grandson Sundara Chola (alias Parantaka II—the father of Rajaraja I, “the Great”) spent his last days there with his Queen Vanavanmahadevi. The Cholas were Saivites. Evidently this explains Rajaraja’s affinity to Chidambaram Temple and the munificent gifts he made to it. Eventually Rajaraja decided to build the great Siva temple at Thanjavur. Originally called Rajarajesvara (now Brihadisvara, or just “the Big Temple”), this edifice with its majestic 216-foot vimanam verily connects earth and heaven. The inscriptions tell us Rajaraja gold plated the entire structure. The mighty tower, dazzling in sunlight, is an awesome sight. Rightly has it been called Dakshinameru.

Copious inscriptions covering the base, walls and pillars of the Thanjavur Temple give detailed accounts by Rajaraja the Great (985-1014ce) and his immediate family. Dr. E. Hultzsch and V. Venkayya published these inscriptions with their translation in English in Volume II of the series South Indian Inscriptions, a colossal feat that rolled out the red carpet for scholars to write factual history of the region.

A Greater Survey

The inscriptions encompass every facet of Chola administration. They record the main divisions, subdivisions and villages in Chola territory, and the extent of Thanjavur city, with the names of its big streets, quarters and bazaars. Information can be gleaned on land survey operations. An extent of land as small as a tiny fraction of a veli (unit of land, about 85 acres) was assessed. Such minute fractions etched in the Thanjavur temple show the ingenuity of Chola-period accountants. Vincent Smith commented, “The lands under cultivation were carefully surveyed and holdings registered at least a century before the famous Great Survey of King William I.” Dry and wet lands were assessed at different rates. Land revenue was payable in paddy or gold. We learn the standard weights and measures used, the prices of commodities, and the exchange value of articles of daily consumption, even food requirements and items consumed by the common man. Detailed tables of wages for different occupations give insight into the job opportunities in those times. The unit of account was gold kasu. Rate of interest was 12.5%.

Chilies seem to be unknown in the Chola country. Botanists believe the plant is not of indigenous origin. More curious is the absence of coconut both in temple worship and ordinary diet. We learn that various kinds of cloth were manufactured. Inscriptions of the great temple at Thanjavur reveal that gold was abundant and silver rare! The art of making jewels and bronze murtis was perfected. People were sufficiently wealthy, and private property was safe.

Engraved on the walls of the central shrine are the fabulous gifts given by King Rajaraja and his venerable sister Kundavi. Grants were made by Queen Lokamahadevi and Rajaraja’s other wives. Inscriptions on the pillars and niches describe copper images of Gods and of canonized Saiva saints installed in the temple by Rajaraja, his many queens, army general, the priest and the manager of the temple. The amount of gold ornaments and gold utensils gifted is incredible; the name, weight and value of each is spelled out. A great variety of rubies, nine gems, their quality and luster are listed. The gifts proclaim the wealth of the Chola dominion of his day.

Ancient Record Keeping

Temple inscriptions served the purpose of registered documentation. Rajaraja’s organizational genius is demonstrated in the systematic manner in which the various endowments were made and the principles laid down for their proper administration. He ordered that every grant made to the Rajarajesvara temple by the royalty, officers, priests and other philanthropists be engraved on stone. Thus we learn the object of each grant, with names of donors, donees, and their ancestry. Land grants have their boundaries mentioned.

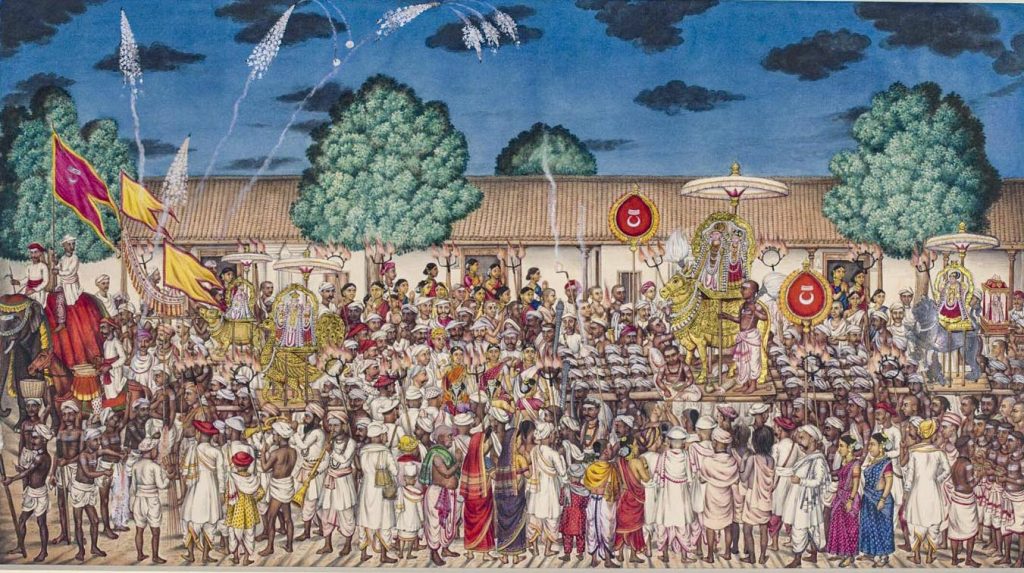

The temple employed people to conduct worship as well as for its maintenance, from Vedic priests down to the sweepers. Their duties, qualifications for recruitment, tenure of office and remuneration are all inscribed. Oduvars and Vedic teachers were paid. Students were given stipends. Sanskrit and Tamil learning was encouraged. Nambiyandar Nambi of Thiruvisaipa was a contemporary of Rajaraja. Saivite literature was patronized, as were music and the arts. The temple maintained dancers, musicians, tailors, cooks, cleaners, torch and flag bearers, as well as fly-whisk and parasol holders. Employees were paid in paddy from temple lands. The temple also functioned as a bank. Money donated to the temple was loaned to village assemblies and corporate guilds; the interest flow was used to procure temple requirements.

During Rajaraja’s reign, we hear for the first time of officers and commissions appointed to enquire into the misappropriation of endowments made to charitable institutions—overhauling accounts, calling for witnesses, taking evidence and punishing offenders. Rajaraja was emulated by his successors, as shown by an inscription in the Siva temple at Kutralam: for misappropriation of temple gold, the priests guilty of the embezzlement were disallowed to enter the premises and lost their means of livelihood.

Rajaraja’s inscriptions also record his political conquests. His dominions comprised the whole of the Madras Presidency, a considerable portion of Mysore State and the island of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). The entire war bounty went into temple construction. We understand he granted several villages in Ceylon to the Thanjavur temple, and they had to remit their assessment in paddy or money. Rajaraja honored his army for his conquests, mentioning 31 regiments and officers in the inscriptions.

Virtually every village had a temple. Village assemblies managed their internal administration and temples. Local and overseas trade prospered. The temple in turn was gifted land and cattle, thereby ensuring a regular supply of paddy, flowers and dairy products for preparation of naivedyam (prasadam) and puja. Culinary enthusiasts will relish the types of prasadams cooked daily and on festival occasions. They were incised in stone with their recipes! Ghee was used to light perpetual lamps. The responsibility for providing every ingredient was pinned to the families of the beneficiaries. Not a single want of the temple was left unattended.

The inscriptions were intended, and respected, as a historical chronicle. An inscription at the Vaidyanatha Temple at Tirumalavadi in Trichinopoly recorded that when its central shrine must be rebuilt, that before pulling down the walls, the inscriptions engraved on them should be copied and re-engraved on the new walls. The king’s successors similarly left complete records of their military achievements and temple renovation work. A record of Kulottunga Chola III (1178-1218ce) from Sivayam, Karur district, states the inscriptions on the walls of the Vinayaka Pillayar shrine in Sivapurisvarar temple were re-engraved after the walls were repaired.

The Thiruvalangadu plates of Rajendra also recorded Rajendra’s military campaigns, including his conquests of Kidaram in lower Burma, and Srivijaya in modern Sumatra. They describe his expedition to procure Ganga water to consecrate the marvelous second Brihadishvara Temple he built at Gangaikonda Cholapuram, his new capital.

In the process, the rulers of Kanuj and Chola kingdoms must have come to an accord. This is established by a damaged inscription of the Gahadavala dynasty of Kanuj found far south of Gangaikonda Cholapuram. The inscription is part of a record in the reign of Kulottunga Chola I, corresponding to the year 1110-11ce. It is inferred that the Gahadavala family might have proposed to make a grant to the new temple there. For some reason the engraving is incomplete. Rulers of Kanuj worshiped Lord Surya as their tutelary deity. Kulottunga was influenced and inspired by them to build the Suryanar Koil in Thanjavur district.

Gangaikonda Cholapuram temple built by Rajendra Chola I is a close imitation of the Thanjavur temple, but the surviving epigraphic records are fragmentary. Wars between English-supported Nawab and the local Poligars in the early 18th century left much of the temple in ruins, and fallen stones were taken for building the lower Kollidam Anicut in 1836, a dam on the Narmada River

We therefore fall back upon Tiruvalangadu copper-plate inscriptions issued by the emperor. These plates record the grant of village Palaiyanur to the Siva temple at the place. The same design of the royal seal found on the ring that binds the copper-plates were in the coins minted by the Chola Emperor. These numismatics are also brought within the fold of epigraphy.

Caring for the People

The Chola kings demonstrated exemplary concern for people’s health and well-being. Inscriptions by Rajendra Chola’s son Veera Rajendra Deva (1063-1069ce), found in Appan Venkatesa Perumal Temple at Thirumukkuda, reveal that the temple ran a hospital which provided ayurvedic treatment and herbal medicines following the ayurvedic text Charaka Samhita. Castor oil is mentioned to reduce excess bile in one’s body. The hospital consisted of 15 beds that functioned in the Jananatha Mandapam there. It was named Veera Cholesvara Hospital. The staff comprised a doctor, a surgeon and two male nurses who brought herbs and firewood to prepare medicines. Two female nurses administered medicines, cooked food and fed the patients. A barber, a washerman, a potter and a gatekeeper were also employed. A lamp was kept burning all night.

Medicines were prepared in the form of medicated ghee, medicated oils and medicated water, made by mixing cardamom and lemon. Nasiyam for nasal and kallikan for ocular treatments were used. Oil application was for reducing body heat; fumigation to correct vatta (air) and pitta (fire/bile) imbalances. Inscriptions by Rajaraja Chola III (1216-1256ce) show he established an asylum to treat mental disorders in the Vedaranyesvara Temple at Nagapattinam.

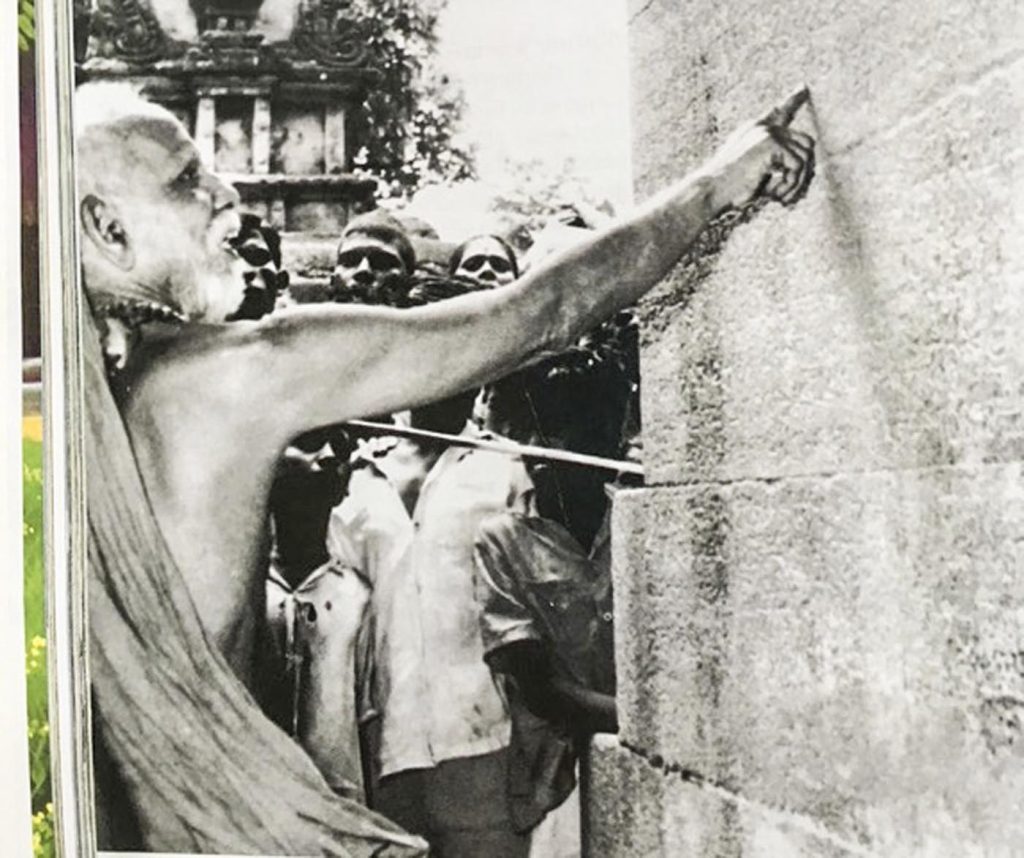

The most important of all South Indian institutions has been the temple. Each is an oasis of peace and calm in the rush of today’s society, yet despite their devotional and historical value, they are often neglected. Temple renovations must be carried out with great care to protect their inscriptions, which preserve our roots, our identity. Many a missing link in history may be supplied by these records.

The dedicated epigraphists of earlier times worked passionately to preserve our cultural heritage by deciphering temple inscriptions. There was no technology, GPS, not even electricity; transport and accommodation (if any) were primitive. Risking their health, they ventured into wilderness and deciphered the inscriptions from derelict temples for posterity. They were great explorers and karma yogis.

The temple is the elixir of our cultural and spiritual life. All mankind has a right to its blessing. It is our duty to see that our temples are maintained in both quality and quantity. Even the smallest act done toward this end will not go in vain, but will yield its results in due time.

About the Author

Sunitha Madhavan is the great grand daughter of Rai Bahadur V. Venkayya, India’s first modern epigraphist. Sunitha currently lives in the Unites States after her 2002 retirement as Professor and Head of the Department of Economics at Meenakshi College following a long college teaching career. She authored the book Life and Works of Rai Bahadur V.Venkayya, published by the Tamil Arts Academy in 2020.

Great to see the arts and images.

I enjoyed reading your article.

I often wonder as i walk through Srirangam Ranganatha temple what the inscriptions carved on

the walls are saying. These writings are in different south Indian languages and also written in various time periods through our history. Some paintings on ceilings have partially survived time, sculptures, along with the tall lofty granite architecture are breathtaking. These structures have stood for more than a millennia yet our modern roads don’t last a year.

I would love to know if our Indian Archaeology has any links or research into the writing, painting, & sculpture work at Srirangam Ranganatha temple.

Fascinating read except for the choice of Ai imagery. Its embarassingly inaccurate.