By the Editor

When I was first told that the Winter Olympics Committee had used its “host nation option” to add a yogic event to the 1998 Games and wanted Hinduism Today to cover the story, I was skeptical. Still, they convinced our editors to fly to Nagano, a modern, narrow-streeted city of 350,000 nestled in the Zenkoji Plain amid Japan’s largest island, Honshu. Only 120 miles northwest of Tokyo, Nagano lies in the midst of majestic mountains–a silk producing region and vacation spot for city dwellers looking to escape urban sprawl.

The moment we arrived, our doubts dispersed. The Committee ushered the Tibetan team to our quarters along with Bikram Singh, India’s only entry. With the help of translators, we were introduced to the newest sport, officially called the YAK Championships, which I soon learned stood not for some exotically high-altitude ox race but for “Yoga and Kundalini.” That’s right, the old mystical arts were being showcased for the entire world to see, and small nations whose national passions incline toward inner striving, instead of baseball or soccer, would have a chance to excel.

Ten days later, on Friday, February 20th, in the packed White Ring where earlier rounds of Figure Skating, Speed Skating and Ice Hockey had been held, we watched the finals, won by a diminutive man with golden skin and rosy cheeks, lithe and liquid and ever so loquacious. This was Sri Khetsun Gyatso, and he had just won Tibet’s first ever Olympic Gold Medal. His elation was electric. “I am the serenest!” Gyatso gloated when his prize was announced. It was a brazen statement, clearly meant to intimidate opponents.

Gyatso fared poorly in the early YAK rounds, which, like the pentathlon, has five distinct events: Hatha Yoga, Breath Control, Zazen (stillness in meditation), Distractions and Timed Transcendence, which requires each athlete, without aids or implements, to attain Sunya, Absolute Nothingness, for one full minute and return to normal consciousness in the same body.

On the first day, Gyatso languished behind Zen Buddhist Roshi Konishi-san in the Double-T, as it is called, which Konishi, a native of Japan and local favorite, won in a mind-obliterating 17 minutes and 57 seconds, a full two minutes under the world’s record. Gyatso, who took 24 minutes flat to transcend, complained that the altitude hampered his efforts. “This is a travesty. I wasn’t myself today. I wasn’t anybody’s Self. I trained at 19,000 feet. The air here at five thousand feet is too dense for our more refined Tibetan style.”

As the days progressed, Gyatso’s youthful will and intensity slowly eroded Konishi’s lead. The Tibetan received a 9.6 in the Hatha Yoga “mandatory postures,” then topped it with a 9.8 in the free-style finals. The Gold Medal in Breath Control went to Bikram Singh, whose average over the one-hour course was .72 IHCs (Inhalation Cycles) per minute. Gyatso was second at .85 with Konishi breathing down his neck at .87. The two tied in Zazen, long assumed by insiders to be Konishi’s event. But he couldn’t, or maybe he just refused to, sit still for Gyatso’s guff and Gorilla dust. Afterwards, Gyatso ratcheted up the verbal jostling: “A tie is as good as a loss for Konishi. Everyone said he would out-Zazen me, but he failed. Tell the world this: Gyatso would have won, derriere down, if the cushions had not been so preposterously soft. They forced us to use zafu Zen pillows. Real yogis don’t use pillows. I challenge these sissies to meditate on a bare rock above Lhasa. These city boys couldn’t handle it.”

Distraction was Nagano’s innovative event. Olympic rules called for each yogi to endure three distinct disturbances: noise, numbing cold and, the toughest, insects. Konishi earned a 9.5 in the Decibel Duel, compared to Gyatso’s paltry 7.9. No doubt Konishi’s access during spring training to sound-polluted Japanese cities gave him the edge. But an undeterred Gyatso brought the astonished crowd to their feet with back-to-back perfect 10s in the Zoological Diversion–where he sat unfazed by mosquitos and even the crawling spiders that ultimately broke Konishi’s concentration–and Cold Exercises, something he had always boasted he could achieve but which had eluded him until now. “Cool!” grinned Gyatso, turning up the heat on his gelid adversaries.

Gyatso, 36, gained prominence on the international yoga circuit when he captured the prized Bharat Padma in New Delhi in 1994, where he introduced his abrasive style. Yoga Federation Commissioner Srila Patel told Hinduism Today that no rules prohibit such braggadocios behavior, though it is considered “unBuddhalike.” “I don’t care what critics say,” Gyatso scorned. “I am who I am. I am also who you are. My mind is as reflective as a mirror. By turning your mind’s negative energies toward me, you only hurt yourself. That’s the first lesson of the kindergarten karma text. Read it and stop whimpering about me. Change yourself…if you can. I dare you.”

Before the Delhi meet, Gyatso had never placed better than fifth. Many said he had forsaken rigorous training for the celebrity status gained from his controversial Nike contract, which showcased him using their new line of Self-Inflating, Ego-Deflating Meditation Mats. His Nagano performance will rank him Number One. In the end, the media found Gyatso’s taunting as daunting as did his foes: “I am the One. Who can compare with Sri Khetsun Gyatso? I am the greatest monk since time began!”

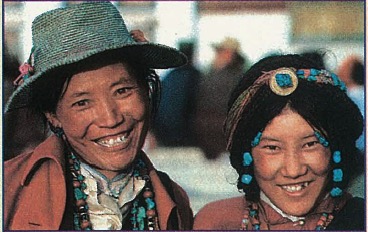

This month’s feature on Tibetan Buddhism is full of pathos, so it may surprise readers to know that Tibetans remain, after all they have endured, a blithe and fun-loving people. As the Dalai Lama once noted: “We Tibetans love all ceremonial and elegant dress; and, perhaps even more important, as a national characteristic, we love a joke. I do not know if we always laugh at the same things as Westerners, but we can almost always find something to laugh about.”