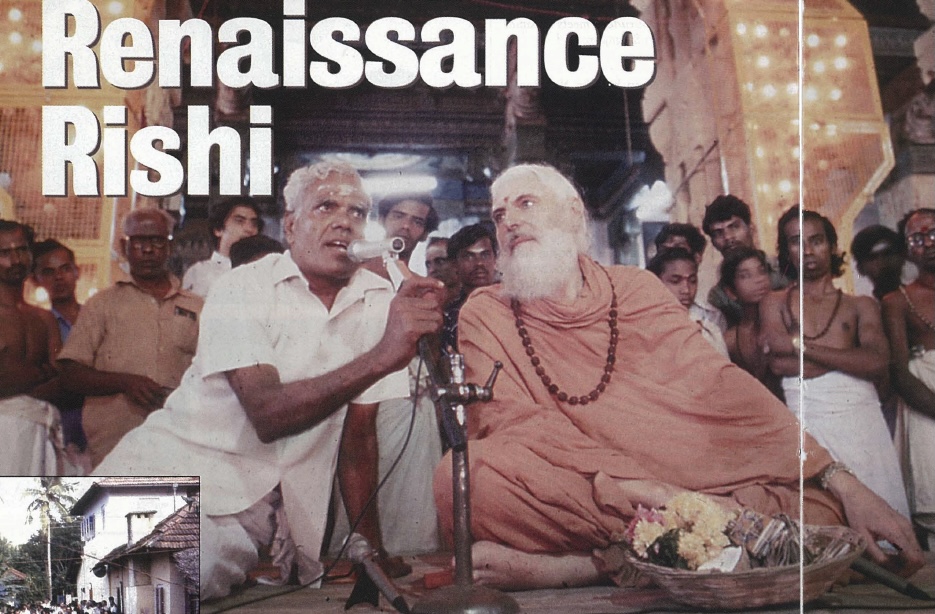

Hinduism is the greatest religion in the world!” Gurudeva thundered from podium after podium during his pilgrimage tours to India, Sri Lanka and Malaysia in the early 1980s. “Stand strong for Hinduism! Be proud to be a Hindu!” he commanded applauding audiences. The pilgrimages, or Innersearch programs, were usually comprised of Gurudeva, six or eight of his monks and 30 or more devotees. The group would travel to the great temples of South India, such as in Chidambaram, Madurai and Palani Hills, and especially through Sri Lanka, homeland of Gurudeva’s lineage. All along the way he would speak to standing-room only gatherings at temples, ashrams and public halls, each pilgrimage carrying a specific message. It was a mission to “convert Hindus to Hinduism,” as said Gurudeva’s friend and fellow worker for the Hindu renaissance, Swami Chinmayananda, characterizing his own aims. It was a mission to be continued, refined and added to up until Gurudeva’s last tour of Europe, weeks before his mahasamadhi in 2001. In the course of it, he met the great saints of India and the world’s outstanding community and political leaders, including presidents and prime ministers.

Gurudeva taught Hinduism to Hindus from the inside out, beginning with explanations of the deepest spiritual world. “The Third World is where the highest beings, such as Lord Ganesha, Lord Murugan and our Great God Siva, exist in shining bodies of golden light,” he explained again and again during the 1981 India Odyssey. “This Third World is called the Sivaloka. The Second World of existence, or astral plane, is called the Devaloka. The great Gods have millions of helpers in the Devaloka who help each and every one of us. One or more of them is assigned to personally help you in this First World, which is the world of material or physical existence, called the Bhuloka.”

He would then explain how the devas can see the sacred ash upon a person’s forehead, how they and the Gods can hear the Sanskrit chanting of the priest in the temple and how the stone icon of the Deity in the temple sanctum is like a telephone connection to the Third World of the Gods. Perhaps his audience had heard such explanations from their grandmothers or grandfathers, but it was quite a different matter to hear Gurudeva teach from his own realization.

The modern renaissance of Hinduism began in the 1800s with the missions of Dayananda Saraswati, founder of the Arya Samaj; Ramakrishna and his disciple Swami Vivekananda, founder of the Ramakrishna Mission; Kadaitswami of Jaffna, in Gurudeva’s own lineage; Sivadayal of the Radhasoami Vaishnava sect; Arumuga Navalar of Jaffna and Ramalingaswami of Tamil Nadu. It included Eknath Ranade, whose social reform thinking inspired Gandhi; Sri Aurobindo, who sought to advance the evolution of human consciousness; Swami Rama Tirtha, who lectured extensively in America; Sadhu Vaswani, Ramana Maharshi and many more. They were dedicated to bringing Hinduism out of centuries of oppression into its rightful place in the modern era.

For all the progress made by these great men, and dozens more since, there remained in 1980 serious obstacles to a true Hindu renaissance. At a time when the “brain drain” was drawing India’s best and brightest to America, perhaps it required GurudevaÑone of America’s best and brightestÑto travel the other way and remind Indians that they had something money couldn’t buy: Hinduism, the greatest religion in the world.

It was to be a tough mission. First, many Hindus wouldn’t even admit they were Hindus. In a lecture in Sri Lanka, he described the problem: “Today there are many Hindus who when asked, ‘Are you a Hindu?’ reply, ‘No, I’m not really a Hindu. I’m nonsectarian, universal, a follower of all religions. I’m a little bit of everything, and a little bit of everybody. Please don’t classify me in any particular way.’ Are these the words of a strong person? No. Too much of this kind of thinking makes the individual weak-minded.” Gurudeva wouldn’t stop there. “They are disclaiming their own sacred heritage for the sake of money and social or intellectual acceptance. How deceptive! How shallow! The word should go out loud and strong: Stand strong for Hinduism, and when you do, you will be strong yourself.”

Closely related to this lack of self-identity as a Hindu was the popular notion that “All religions are one.” Hindus don’t need to claim to be Hindus, went this line of thought, because it doesn’t really matter what religion you follow, since all are the same. Gurudeva countered, “All religions are not one. They are very, very different. They all worship and talk about God, yes, but they do not all lead their followers to the same spiritual goal. The Christians are not seeking God within themselves. They do not see God as all-pervasive. Jews, Christians and Muslims do not believe that there is more than one life or that there is such a thing as karma. They simply do not accept these beliefs. They are heresy to them.” He had his monks research the beliefs of all the major faiths and clearly delineate one from another.

Going against a common trend, he preached the merits of sectarianism, of each of the great traditions of Hinduism- Saivism, Vaishnavism, Shaktism and Smartism retaining and valuing their unique features. The watered-down, homogenized Hinduism which some were advocating, he warned, would not sustain the individual sampradayas, spiritual teaching traditions, which are its core strengths.

One of India’s leading writers, Sita Ram Goel, said, “Gurudeva’s greatest contribution has been to rescue the word Hinduism from being a dirty word and restore it to its age-old glory. He made Hindus everywhere to see themselves as a world community and as inheritors of a great civilization and culture.” Swami Advaitananda of the Brahma Vidya Ashrama in India said it this way: “In the present days, when Hindus are ashamed to call themselves so, it has been his work and teachings that have propelled faith and infused dynamism among the millions who lovingly addressed him as Gurudeva.”

Gurudeva was astonished at the pervasive Christian influence in India, even though just two percent of Indians were Christians and even though the British had left fifty years ago. He found those in India educated in Christian schools to be anemic Hindus, their faith undermined by the years of study under teachers propounding an alien faith. One Catholic priest in Colombo even told him straight out, “The Hindu children that pass through my school may never become Catholics, but they certainly will never be good Hindus.”

Gurudeva had nothing against Christianity or any other religion. He came, after all, from a country where Christians are in the majority. Only rarely in his years of ministry in America did he experience any Christian interference. In his early years, he studied with deeply mystical teachers of several religions, including Buddhists, Muslims and Christians. He knew the finer side of each faith.

What he saw at the Christian schools was bad enough, but the methods of Christian missionaries trickery, enticement, intimidation incensed him. He opposed this devious side of Christianity wherever he found it and told the Hindus worldwide to stand by their religious rights as Hindus. “When an elephant is young,” he said time and again, “the mahout, trainer, can control it with a small stick, and the elephant learns to fear that stick. When the elephant is big, he still fears the stick, even though he could pick it up and the mahout, too, and toss them far away.” By this same psychology, Gurudeva said, Hindus had become meek and submissive under years of Christian rule and unwilling now to mount serious protest to continued Christian oppression, even when the political power which made it possible in the first place was gone. His advice was not to attack the Christians, but to disengage from and ignore them. He told Hindus to take their children out of Christian schools and to close their doors on Christian missionaries who came to their homes to proselytize.

A few Hindus opposed Gurudeva, unsure of what he was trying to do, or feeling perhaps that their “turf” was being invaded by an outsider. In 1999, he told his students on the Alaska Innersearch program about this time. “We did not fight themÑ’them’ is ‘us’Ñbut let them find out that we were all working for the same thing, the upliftment of Hinduism.” And over the years they did, until Gurudeva humorously lamented, “I am so disappointed in my enemies. Not one has ever been able to stay mad at me.”

Gurudeva preached and practiced cooperation among Hindus. Three harmful habits stood in the way: attacking leaders, tolerating detractors and disharmony among boards and committees. “It is important that you refrain from the pattern that if one person in the community comes up, cut him down, malign him, criticize him until all heads are leveled,” he said. “In modern, industrial society everyone tries to lift everyone else up. People are proud of an individual in the community who comes up, and they help the next one behind him to succeed as well. They are proud of their religious leaders, too. Not so here in India, because if anyone does want to help out spiritually they have to be quiet and conceal themselves, lest they be maligned. Nobody is standing up to defend the religion; nobody is allowing anybody else to stand up, either. This has to change, and change fast it will.”

“Swami bashing” was another sport Gurudeva would not tolerate. Its origins were easily detected Christian missionaries on one side and communists on the other, each for their own reasons wanting todiscredit the swamis. Gurudeva later said, “When swami bashing was in vogue years ago, swamis took it seriously. They got to know each other better, stood up for each other and put a stop to the nonsense.” Gurudeva made a point of meeting as many of the swamis of India as possible. He stayed in contact with them, too, especially through Hinduism Today, and gathered their views on dozens of issues to formulate an all-Hindu stance and to empower spiritual leaders.

His perceptions about detractors were more subtle, and came to the fore as his renaissance mission matured in the late ’80s and ’90s and encompassed Hindus of the diaspora in dozens of countries. It was the result of years of experience with Hindu and non-Hindu organizations. The detractor, he explained, was the person who joined a religious group to socialize, but did not really support its aims. Such people, he said, can completely stymie a group’s efforts. “At meetings they are quite competent to tell in compelling terms why a project that all wish to manifest is not possible,” he said. “They are equally capable of making everyone question the mission of the organization and their part in it.”

It was a subtle perception, but perfectly clear for those facing detractors, such as a committee in the UK formed to build a Hindu temple. They even had one Christian and one communist as board members. Their purpose, one trustee memorably wrote, was “to infiltrate, dilute and destroy” the purpose of the committee. On his next visit to London, Gurudeva saw to it that the detractors were excused from the board.

Weeding out detractors was only a first step in making Hindu organizations, especially temple boards, more effective. Some in the West were famous for their rancorous meetings, with some disputes even spilling into the local courts, to the great embarrassment of the community. When trustees approached Gurudeva for advice, which many did, he emphasized the absolute necessity of harmony among board members, the same harmony he demanded of his monastic order. “Why,” he would ask, “can’t a board comprised of professional doctors and engineers get along in a professional manner? Do they have to forget their diplomatic skills mandatory at their regular jobs?” The advice was helpful to many communities, who realized that no good work, especially the construction of a Hindu temple, was going to come out of meetings where tempers flared. Anger, jealousy and ego, he said, will derail any spiritual project.

He stood ready to defend the priesthood who serve in the Hindu temples around the world. He defended the rights of the Sivachariyas, the highest order of Saivite priests. One of their leaders, Sri T. S. Sambamurthy Sivacharyiar, wrote, “His support to us was great. At a time when many organizations and even governments were discouraging us, he always raised his voice on behalf of us around the world at difficult times.”

Gurudeva criticized those who claimed social superiority by virtue of caste. He said, “I don’t understand how some people claim they are brahmins because their fathers are brahmins. They don’t know the religion, and they can’t do the worship. It’s like someone saying, ‘My father is a doctor, so I’m a doctor. Let me operate on you.’ No way.”

In Europe and America he advocated proper treatment of the priests, especially that they be given decent salaries, proper working conditions, reasonable hours and good housing. He wanted them to be represented on temple boards and be given the respect and position that priests and ministers of other faiths enjoy in the West, akin to that of a doctor or a lawyer. It wasn’t his most popular suggestion, especially to temple boards comprised of “brahmins.” As an alternative, he encouraged priests to start their own temples, which a few have done and more plan to in the future.

He addressed a special part of his message to his fellow Saivites to dispel the common misconception that Lord Siva should not be worshiped in the home, and that the worship of Siva would make one poor. “Nonsense,” he said, “Lord Siva is the God of Love” and explained that worship of Siva would bring every benefit, including wealth.

He wanted all the Gods brought “out of exile” and encouraged Hindus of each sect to make their home shrine the most beautiful room in the house. He reserved a special condemnation for those Hindus in the West who put their shrine in the closet, easily hidden when a guest visited. The house should proudly and openly reflect its religion and culture of the residents, he taught.

At a time when vocal advocates of a militant Hinduism arose, Gurudeva stood firm in defense of ahimsa, nonviolence, as an essential principle. Yet, he was not a pacifist. He endorsed the right of nations and individuals to self-defense. But he could foresee the negative karma and endless cycles of retribution in store for those who advocated violence, taking the law into their own hands to achieve their goals or to right past wrongs. This was not always the popular stance, but with scripture and the majority of swamis backing him up, one heard fewer and fewer Hindus advocating violent solutions.

Gurudeva didn’t just advise communities what should be done; he set about doing it, especially through his publications. The books filled the gap for well-written explanations on Hinduism. Swami Bua, age 115, wrote, “Gurudeva’s unique method of explaining the most complex principles in the simplest way was astounding. That was how he could reach more people. The most complicated philosophies appeared as the simplest and easiest messages in his handsÑbut with the same power and essence.”

Gurudeva’s renaissance message included Hindu pride, clear and public religious identity, correct religious understanding, reverence for scripture, respect for religious leaders, home worship, opposition to conversion, preservation of traditions, harmonious working together, interfaith harmony, Lord Siva as the God of Love and Hinduism as best suited of all religious for the modern, technological age. He dispelled many myths and misunderstandings about Hindus among Hindus and non-Hindus alike. He advocated a strong and loving Hindu home, encouraging mothers to not work but raise their children full-time and for parents to not use corporal punishment on children. He projected this message with clarity, boldness, love and humor, and he made a difference, redefining our modern Hindu world.

RENAISSANCE GURU

A Global Touch

Gurudeva brought an articulate, dynamic Hindu presence to world religious conferences

Gurudeva only occasionally attended conferences, though he was often invited. He found significant the Global Forums of Spiritual and Parliamentary Leaders on Human Survival in Oxford (1988), Moscow (1990) and Rio (1992), the Parliament of World Religions in Chicago (1993) and the Millennium Peace Summit of World Religious and Spiritual Leaders at the UN in 2000. “Russia was the most interesting of the Global Forums,” Gurudeva reminisced last year. “It was sort of a captured group. You couldn’t go out of the hotel or conference hall, because it was so cold.” Day after day the religious leaders and the political leaders (from 57 nations) discussed the problems of the world. “We found out humanity is on the endangered species list,” said Gurudeva, “right along with the whales and birds, and it was kind of embarrassing to find that out.”

He created quite a stir at this meeting when one of the religious leaders was slighted. It occurred at a plenary session opening blessing. After an elegant African priestess concluded the opening prayer, the panel moderator said, “Now let’s get on to the real business of the day.” Gurudeva took exception to this remark, telling the organizers that they had invited the spiritual leaders to work with the political leaders, but instead had them come up and give some little prayer, then insult their presence and diminish their participation. “She is the real business of the day,” he scolded them, “as much as everything else, and you’ve really offended every spiritual tradition by pronouncing that we’re just here as wallpaper to your meeting.” The chairperson apologized, and the rest of the week spiritual leaders were eagerly brought forward and honored properly.

While he found value in conferences, and had his Hinduism Today staff assist organizers, he found the meetings inefficient, boring, repetitive and woefully lacking in follow-through on the issues discussed after the event was over. He complained about meeting the same people time and again, making the same well-meaning resolutions, then forgetting all about it. He tried to keep the group of 25 “presidents” of religion, of which he was one of three Hindus, going after the Chicago Parliament of the World Religions. He felt this group could occasionally make statements on important issues. But there was little interest, and nothing came of it, despite his repeated efforts.

Kusumita Pedersen, a devotee of Sri Chinmoy and on the staff of the Global Forum, Parliament and UN organizing committees, commended Gurudeva’s participation at the international conferences for “his powerful spiritual presence and his great clarity and commitment in engaging the issues. Also, his behind-the-scenes contribution has made a little known but historic difference to the development of interfaith work in the last generation.”

Stop the War in the Home

Excerpts from Gurudeva’s 2001 Message at the UN

When asked by the United Nations leaders how humanity might better resolve the conflicts, hostilities and violent happenings that plague every nation, I answered that we must work at the source and cause, not with the symptoms.

To stop the wars in the world, our best long-term solution is to stop the war in the home. It is here that hatred begins, that animosities with those who are different from us are nurtured, that battered children learn to solve their problems with violence. This is true of every religious community. Not one is exempt.

This is a global problem, in all communities, but I believe that Hindus have the power to change it because our philosophy supports a better way. If we can end the war in our homes, then perhaps we can be an example to others, and this will lead to ending war in the world. People will choose a different path.

Sadly, in this day and age, beating the kids is just a way of life in many families. Nearly everyone was beaten a little as a child, so they beat their kids, and their kids will beat their kids, and those kids will beat their kids. Older brothers will beat younger brothers. Brothers will beat sisters. You can see what families are creating in this endless cycle of violence: little warriors. One day a war will come up, and it will be easy for a young person who has been beaten without mercy to pick up a gun and kill somebody without conscience, and even take pleasure in doing so.

I’ve had Hindus tell me, “Slapping or caning children to make them obey is just part of our culture.” I don’t think so. Hindu culture is a culture of kindness. Hindu culture teaches ahimsa, noninjury, physically, mentally and emotionally. It preaches against himsa, hurtfulness. It may be British Christian cultureÑwhich for 150 years taught Hindus in India the Biblical adage, “Spare the rod and spoil the child”Ñbut it’s not Hindu culture to beat the light out of the eyes of children, to beat the trust out of them, to beat the intelligence out of them and force them to go along with everything in a mindless way, then take their built-up anger out on their children and beat that generation down to nothingness. This is certainly not the culture of an intelligent future. It is a culture that will perpetuate every kind of hostility. Corporal punishment is arguably a prelude to gangs on the streets and those who will riot on call

Now, is this the Hinduism of tomorrow? We hope not. But this is the Hinduism of today. It can be corrected by all of you going forth to bring peace within every family and every home. If you know about the crime of a beating of a child or a wife, you are party to that crime unless you do something to protect that wife or to protect that child.

In the past 85 years we’ve had two world wars and hundreds of smaller ones. Killers come from among those who have been beaten. The slap and pinch, the sting of the paddle, the lash of the strap, the blows of a cane must manifest through those who receive them into the lives of others.

We do know a few Hindu families who have never beaten their children or disciplined them physically in any way. We ask them “Why?” They say, “Because we love our children. We love them.” “So, how do you train them, how do you discipline them?” “Well, we have them go into the shrine room and sit for 10 minutes and think over what they did wrong, and they come back and we talk to them. We communicate. We encourage them to do better, rather than making them feel worse.”

Holding the family together can be summed up in one word: love. Love is understanding. Love is acceptance. Love is making somebody feel good about his experience, whether the experience is a good one or not. Love is giving the assurance that there is no need to keep secrets, no matter what has happened. Love is wanting to be with members of the family.

When harmony persists in the home, harmony abides in the community, and harmony exists in the country. When love and trust is in the family, love and trust extend to the local community, and if enough homes have this harmony among members, the entire country becomes stronger and more secure. Let us determine then to call a truce in every Hindu home, then a truce in our communities leading to a longed-for truce among nations. This is something each and every one of us can do to put an end to wars.

SOLIDARITY

Uniting the Hindu World

From modest beginnings, HINDUISM TODAY evolved into a world-class magazine

BY LAVINA MELWANI, NEW YORK

lassiwithlavina.com [http://www.lassiwithlavina.com]

In the early 1980s,” Gurudeva told me, “I made several world tours, visiting Mauritius, Sri Lanka, India, South Africa, Malaysia, England and other countries, and speaking to hundreds of thousands of people. I discovered that Hindus in each country were totally unaware of, or did not care, what was happening within the realms of their religion in other places in the world. Out of these tours came the mission of Hinduism Today to strengthen all the many diverse expressions of Hindu spirituality and to give them a single, combined voice because everywhere else their voices were individualized. Through this magazine, we delineated the boundaries of Hinduism and placed this great and oldest religion alongside Islam, Christianity, Judaism, Jainism, Sikhism and the many other religions of the world. We showed the strength of Hinduism in articles by top writers and some of the finest photographers in the world, such as for our articles on the Kumbha Mela, the largest human gathering ever on planet Earth. We have been able to bring forward and honor a ‘Hindu of the Year’ and to listen to the wisdom of swamis and swaminis every month in our ‘Minister’s Message.'”

“Every religious order has a mission,” Gurudeva went on. “Instead of starting an eye-clinic or an orphanage, we created a global publication to advance the cause of Hinduism and record its modern history. Through the years, we went through many learning curves to bring Hinduism Today up to the standard it is today. It is the only religious magazine that we see on newsstands these days, right alongside Newsweek and Time.” He commissioned his monks to promote all Hindu denominations in the magazine, to report “everybody’s good work” and to never use the magazine solely for the promotion of our own mission and purposes.

Paramacharya Palaniswami, the editor of Hinduism Today, elaborated for me upon Gurudeva’s vision. “Opening up many books on Hinduism, they are so cluttered with technical terms, obscure references and other languages that the average seeker would go about three pages and not pursue it further.” Hinduism Today wanted to say all the important things, the profound things, but in an interesting voice which all could understand and appreciate. While Hindus living in India are surrounded by their culture and faith, Hinduism Today’s mandate was to also reach the millions of Hindus who are trying to keep their faith alive in far-off places surrounded by different cultures. In isolated, alien townships and cities, shared words can provide courage, enthusiasm and energy to keep true to a faith. Hinduism Today tells the world about India’s cultural riches: ayurveda, classical dance, literature and drama, the healing power of meditation and yoga and the virtues of vegetarianism. To those who are Hindu and to those merely attracted by the principles of Indian spirituality, it offers a common platform, a feeling of family, a source of good vibrations. “Affirming Sanatana Dharma and recording the modern history of a billion-strong global religion in renaissance” is its mission statement.

Hinduism Today reaches Hindus in 60 countries. Readers also include seekers of every ethnic group and religion who are attracted to the sublime philosophies of Sanatana Dharma. Surprisingly, a few subscribers are clergy and theological students of other major religions. For second-generation Indians growing up in foreign lands the magazine provides answers to perplexing questions in an intelligent and easily accessible way. It helps the children who have to deal with classmates who ask questions like, “Why do you worship cows?”

Back in 1987, the late Ram Swarup, then India’s foremost spokesman for Hinduism, clearly caught Gurudeva’s vision: “I personally believe that Hinduism Today is doing God’s work,” he wrote. “Posterity will realize that it was an important landmark in the history of the reawakening of Hinduism. It is already helping the Hindus of the American hemisphere to retain their self-identity. It is also an inspiration to many of us here. It must remain the mouthpiece of the Sanatana Dharma and renascent Hinduism and carry this message to all who care for it.”

After John Dart of the Los Angeles Times listed Hinduism Today as a prime source in his book, Deities and Deadlines, the magazine has fielded calls from religion editors around the country, including from Time magazine. Most surprising to the staff, however, was a request from Houghton Mifflin, one of America’s largest publishers for children’s textbooks in middle and high schools, to vet its chapters on Hinduism for a civilization series for sixth graders destined for school rooms where half a million 13-year-olds will study it in the United States. Houghton Mifflin had called Harvard to critique the chapters, and Harvard referred them to Hinduism Today. Recalls Palaniswami, “The two chapters were awful, devastatingly bad, even wrong in places. We ended up rewriting the whole thing, and also provided graphics. The chapters on other religions had really nice graphics, but for Hinduism they had found a horrible, monster-looking Siva for these young children to study. We sent them elegant, graceful images that Hindus would be proud to see.” To the amazement of the magazine team, the publishers adopted the rewritten chapters, and as a result American kids will have an authentic and compelling introduction to the world’s oldest religion, not some demeaning stereotype.

Many religious journals walk a tightrope between propaganda and journalism, but Hinduism Today has always chosen the harder path of insightful reporting. Says Palaniswami: “Happily, we are not just ‘another bhakti rag,’ as one reader observed. While remaining upbeat, we do try to tell readers even about the painful underbelly of one-sixth of the human race’s religion, Hinduism, to make it real and not paint an unrealistic or Pollyanna picture. It’s important to express things in that way; otherwise people stop listening.” Gurudeva added, “We only report the news after verification, and we always show both sides of controversial issues.” They’re not afraid to discuss tough social topics like wife battering, bride burnings, child abuse or the fact that Indian girls have the highest suicide rate. Interviews with strong Hindu women such as Madhu Kishwar, activist editor of Manushi, animal rights activist Maneka Gandhi and prison reformer Kiran Bedi are part of the consciousness-raising features.

While the core team is composed of monks, Hinduism Today has over 100 journalists and dozens of photographers and artists working for it worldwide. These people live in the community and understand the problems modern Hindus face. The majority of contributors are Hindu women.

Beginning in November, 2000, the magazine added a daily e-mail news summary service, Hindu Press International, as a means to distribute the constant stream of stories about Hinduism appearing in the world press. A team of a dozen work to find news on the Internet and in print and distill it to one-paragraph summaries. HPI has filled a gap for the magazine by providing a means to instantly release timely stories and others unsuited to the magazine format.

Over the years Hinduism Today has picked up the cudgels on behalf of persecuted Hindus in Fiji, Dubai, South Africa, Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Kashmir. Without being highlighted in the press, these victims would have disappeared from human memory. There have been stories about Nepal, the only Hindu nation, being stormed by foreign missionaries. There were only 25 baptized Nepalese Christians in 1960. The figure by 1994 had grown to 120,000. One rarely sees such stories in the press. With its countless success stories of important CEOs, artists, entrepreneurs and intellectuals unabashedly Hindu, Hinduism Today has pinpointed role models for a new generation to follow.

Gurudeva’s legacy highlights all that is good about Hinduism, with none of the infighting or fundamentalism. Always contemporary, witty and able to solve problems, he bridged cultural and language barriers and presented Hinduism in an accessible way to mainstream Americans and first generation Indian-Americans alike. Ma Yoga Shakti, a New York-based spiritual teacher, called him a Hanuman of today. Indeed, through his innovative and untiring efforts, he carried the pennant of Hinduism aloft in America.