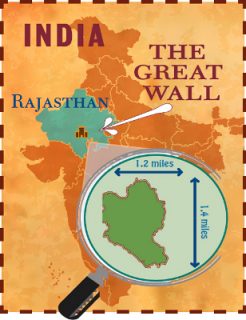

The untold history of Kumbhalgarh, Rajasthan’s most famous fort, surrounded by a massive 23-mile-long rampart that is second only to China’s Great Wall

BY ANNESHA SENGUPTA, NEW YORK CITY

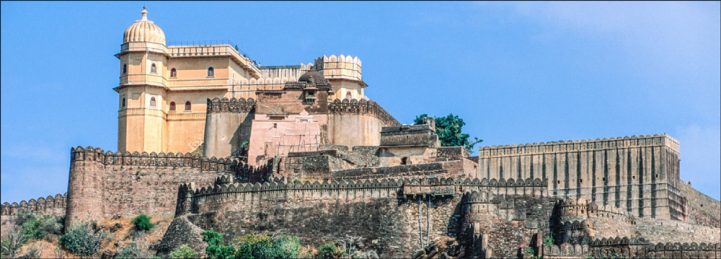

SIXTY-FOUR KILOMETERS FROM THE city of Udaipur, formerly the capital of the Mewar Kingdom, sits the elaborate Kumbhalgarh Fort. At first glance, it appears like a mirage—the harsh yet beautifully constructed buildings create a somber silhouette atop the Aravalli mountains. The fort, perched 3,600 feet above sea level, is one of the loftiest jewels in Rajasthan. Taking nearly a century to complete, it was begun under the supervision of master architect Mandan on the side of an even more ancient castle built by Samprati, a Jain prince of the second century bce.

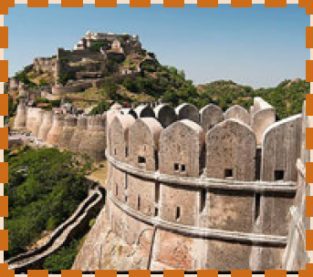

Perhaps even more astonishing than the fort is the surrounding wall and parapets. At almost 23 miles long, it’s the second longest wall in the world, second only to China’s Great Wall. At most sections it is 15 feet wide, but broader stretches reach 49 feet. Legend claims eight horsemen could ride side by side at the top. At each of its seven gates is a formidable rampart with circular bastions for archers and other fighters. The ramparts were often folded within each other in places where the wall was crenelated.

But unlike the Great Wall, Kumbhalgarh Fort contains a powerful religious influence, with large and ornate temples. Today, Kumbhalgarh Fort is one of Rajasthan’s best kept secrets, with much of the rich folklore and history known only by local historians and academics. The historical king Rana Kumbha (1433–1468), constructed it in the 15th century, completing the main section after 15 years. When finished, it proved to be one of the most impenetrable fortresses known to man. Strategically situated on steep, high ground, the fort contained all the supplies necessary to withstand long, tedious sieges. Water was always in full supply from the nearby Banas River, and the heavily fortified battlements could withstand heavy bombardment. In all its 500 years as a stronghold of the Mewar Kingdom, it was only captured once. That happened in when the Mughal army took advantage of a drought (some claim they poisoned the water supply), but the Rajasthanis recaptured it just days later. “If you wish to enter [the fort],” wrote scholar Onkar Rathor, “you have to become a mosquito.”

The fort’s creation is shrouded in mythology. It is said that when Rana Kumbha first started construction, whatever his workers built each day would crumble to ruins by sunset. A priest informed the monarch that the fort could not be built until someone voluntarily gave their life as a spiritual sacrifice. For months, no one could be found, until one pilgrim (who in some versions is a soldier from Rana’s troops) volunteered and was ritually dispatched. From that moment on, the fort blossomed on the mountainside. From this origin story stems the history of the fort as a place of war and religion, bloodshed and peace.

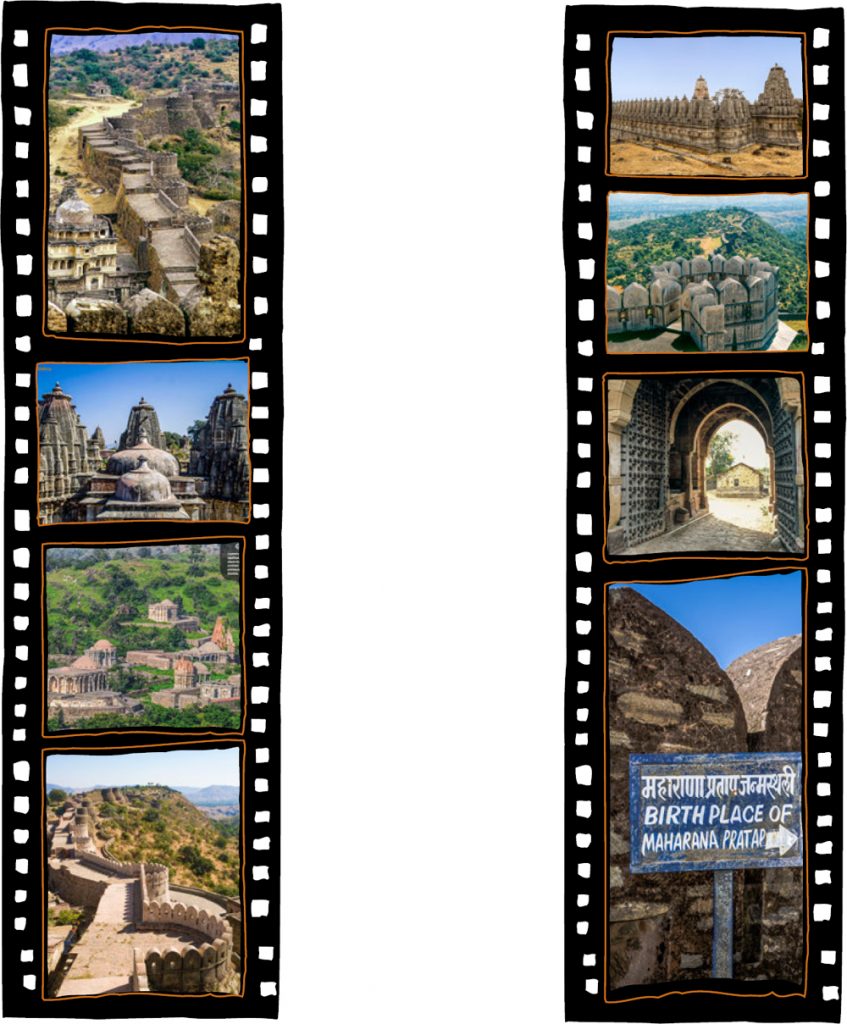

A Jain temple inside the wall; typical embattlement detail; one of the seven entry gates; sign leading to the king’s birthplace; the wall from above; the Golera group of shrines; towers of a Hindu temple; the wall’s wide walkways.

While Rana Kumbha was a real, historical figure, the stalwart leader of the Mewar kingdom, he has picked up mythological characteristics throughout the years. Formidable on the battlefield, famous for capturing the city of Nagaur, he commissioned over 31 other Rajasthani fortresses, and also oversaw the construction of the 121-foot-tall Vijay Stambha, the Victory Tower of Vishnu. He was an accomplished wrestler, artist and poet, the author of 13,000 couplets. It is said he was eight feet tall, one reason that many of the temple Sivalingams are enormous, as they were designed, per tradition, to equate with the king’s stature. During his reign, the fort was not overcome once.

Unfortunately, Rana Kumbha’s glorious life came to an inglorious end when, at age 35, he was murdered by his own son, Udai Singh I, in 1468. At that point Kumbhalgarh temporarily lost its glory. The patricidal son did not live long after the murder. He was struck by lightning in Delhi while traveling to offer his daughter’s hand in marriage to the Delhi Sultan. This is seen by many as divine justice for his gestures toward the enemy. Kumbhalgarh then lay nearly forgotten for over seventy years.

This changed in 1540 with the birth of Rana Pratap, one of the most respected warriors of Indian history. Rana Pratap, born within the confines of the fort, rejuvenated interest in the area as a place of history, politics and war. His archenemy was Akbar, more popularly known as Akbar I or Akbar the Great. Rana Pratap spent his entire life fighting the Mughal Empire at a time when resistance to the foreign invaders’ larger armies seemed futile. The Mughals breached the fort only once, but it was taken back by Rana Pratap within a matter of days. He would go on to spend most of his life in Kumbhalgarh, dying of hunting injuries at the age of 56.

Defensive bastions: A few of the massive round bastions with parapets above to give soldiers protected spaces

A quick glance at the structure of the fort’s interior reveals the priorities of its creators. The residential structures are sparse and utilitarian, almost entirely devoid of ornamentation. These are flat-roofed structures made of rubble stone or broken scrap stone with little ornamental beauty, while the great wall was made of large premium stone blocks from the surrounding mountains. The multitudinous temples that dot the fort and wall are stunningly elaborate, full of intricate work carved by thousands of artisans, who often utilized rare and stunning black stone, showing the culture’s reverence for these religious edifices. There are over 360 temples within the wall’s confines, mostly Jain, while many of the largest are Hindu. While Rana Kumbha built the fort for defensive purposes, he was clearly just as interested in providing his citizens with places of worship.

The largest, a Siva temple, has over 52 canopies, an expansive courtyard and a pillared corridor. The ceilings, rounded and beautiful, stand above statues of several Deity murtis, including Siva and Hanuman, that reach from the floor to the top of the roof. This creates the illusion that the Gods themselves are holding the temple aloft and betrays the fundamental wartime purpose of the fort. Hinduism is no minor adornment here. Rather, it is the very cornerstone of the citadel—the artistic and military power of its success. Rana Kumbha regarded all his endeavors as holy, a perspective that his successor, Rana Pratap, would also come to hold. No part of the fort—its defense, its picturesque surroundings, its harbouring of Jain merchants—could exist without the Gods.

The Siva temple was built in the middle of the 15th century, shortly after the main structures went up. It is a stupendous feat of architecture—a wide, round dome with a heavy and intricately designed roof held aloft by 24 massive pillars. Nandi the bull, the mount of Lord Siva and protector of His ancestral home, Mount Kailash, stands statuesque at the temple’s entrance. The Sivalingam is five feet high and made of black stone.

Some distance from that citadel sits a Jain temple to Ganesha with an intricately decorated roof that appears like a dome when viewed from afar. Nearby are statues of Brahma, Vishnu and Siva. This is part of a complex of nine coexisting Hindu and Jain shrines. Many of the tenants of Kumbhalgarh Fort were wealthy Jain merchants who had allied themselves with Rana Kumbha and lived here in religious and diplomatic harmony. One of the most famous of the Jain temples stands on a platform rising above the flat ground and is devoid of any idol. The layout is simple, but the stones adorning the gate are elaborately carved with scenes from the Mahabharata and delicate figures of temple dancers.

The Vedi Temple, three stories tall, is a sacrificial shrine located near the famous Hanuman Gate. It was built by Rana Kumbha and later renovated by Maharana Fateh Singh. It is the final remnant of India’s ancient sacrificial temples.

While Kumbhalgarh is a popular tourist destination for those living nearby in Rajasthan, it has not achieved nearly as much popularity as its closest counterpart, the Great Wall of China. This is curious, because although the Kumbhalgarh Wall is vastly shorter than the Great Wall, there are many features in Kumbhalgarh that are worthy of fame. The Great Wall, for example, was purely military in purpose, and does not give space for temples and monuments. The Great Wall was not connected by a single fort that also functioned as a ruler’s court—it worked as a border, not as a center. Remarkably, Kumbhalgarh manages to do both. Tourists and locals who visit Kumbhalgarh describe being overwhelmed by its grandiosity, its cultural complexity and the breath-taking surrounding landscape.

Baudhayan Lahiri, an IT professional who is also an avid traveller, photographer and videographer, describes his experience: “After entering the fort, we first had a lunch break and then commenced our journey upwards. While quite a steep climb, we still enjoyed as the weather was pleasant and the views became more and more amazing. After a climb of almost 1.5 hours, we finally reached the top which was extremely windy and provided stunning panoramic views of the Aravali mountain range. What amazed me was that other than the main fort boundary there are other walls built across the mountainous range around which demarcated the area of governance and control. The walls extended for miles around, and I had to use my binoculars to see them.”

Inside the fort’s courtyard.

Kumbhalgarh lies not only at the intersection of government and religion, but religion and aesthetics. Everything about Kumbhalgarh is absolutely beautiful, from its carefully designed interior to the sweeping views outside. The fort intentionally becomes part of the landscape, and both the beauty of the fort and the beauty of its locale serve as a testament to Kumbha’s faith in the beauty of all things created by God.

In 2013, Kumbhalgarh Fort, along with five other forts of Rajasthan, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is finally protected by both the government and groups of dedicated scholars and archaeologists. Now that it is no longer private property, Kumbhalgarh is not used as a residence. Its significant upkeep is overseen by the government of Rajasthan. The fort maintains its cultural importance in the surrounding community. Every year, the Rajasthan Tourism Department organizes a three-day festival in honor of Kumbha and his contribution to the arts. The festival includes a Heritage Fort Walk, turban tying, tug-of-war and mehindi for adults and children. It remains the perfect tourist attraction, reachable by air from Udaipur (85km away), by train via the Falna railhead (80km away) and by road via private cars and buses. The recently released book, Wonderful India, Kumbhalgarh the Majestic, by Amit Tejwani and photographer Kapil Tejwani, contains the best photos you will see of the site and a wealth of information on the fort’s history and architecture.

Kumbhalgarh Fort has the second largest parapet wall in the world and is the second largest fort in Rajasthan. However often the fort is demoted to being second, it refuses to be overshadowed. Within its delicately carved temples and sparse yet majestic rooms is the birthplace of Rana Pratap and the fascinating history his reign inspired. Its architecture tells the story of the warrior king Kumbha and all those who lived with him, died with him and even fought against him. It is a place of religious harmony, where Jain and Hindu temples coexisted, and where faith was prioritized above war and politics. Kumbhalgarh Fort remains a testament to humanity, courage, the Hindu faith, religious synergy and time itself.

Great videos of the fort can be found here:

youtube.com/watch?v=o5WNv5-IuzI

youtube.com/watch?v=_w9BWbhJ4HA

youtube.com/watch?v=dmRr7lWbUcs

Fort Factoids

RAJASTHAN IS HOME TO SOME OF THE WORLD’S GREATEST FORTS. AMONG THEM KUMB-halgarh stands apart, not because the fortress itself is especially magnificent (which it is), but because of the great wall that surrounds and protects it.

The fort which the wall surrounds is built high on a steep hillside and dominates the landscape, being more than 1,000 meters above sea level. The kings of those days hoped that the protection of the wall would avoid violence simply because any advancing enemy could not penetrate it. The wall was constructed half a millennium ago (work began in 1443, about the time the printing press was invented), in tandem with Kumbhalgarh Fort itself, the second most significant citadel after Chittorgarh in the Mewar region. It is one of 32 forts built by the Rajput rulers of the Mewar kingdom. The virtually unassailable fort boasts seven gigantic gateways, called pols, and seven ramparts strengthened by rounded bastions and massive watchtowers.

Tourists find it pleasant to have this extensive, well-preserved but not not well-trafficked site to themselves, a feature of the many miles they had to travel through the desert to reach it. Though clever traps and defensive mechanisms along the wall and within the fort have been deactivated, visitors are still warned to be careful, especially when approaching badly deteriorating areas. Guest quarters and restaurants have been opened inside the fort itself, making for an immersive experience.

Within the walls stand more than 360 Jain and Hindu temples. A delightful palace, aptly named Badal Mahal or the Cloud Palace, sits at the summit. From the palace roof, one can see several kilometers into the Aravalli Range and the sand dunes of the popular Thar Desert. According to local folklore, Maharana Kumbha used to burn huge lamps that consumed 50 kilograms of ghee and 100 kilograms of cotton each night to provide light for the farmers who worked the fields during the nights in the valley.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has successfully protected the site, which includes five other majestic forts: Chittorgarh; Sawai Madhopur; Jhalawar; Jaipur and Jaisalmer. The eclectic architecture bears testimony to the power of the Rajput princely states that flourished in the region from the 8th to the 18th centuries. Enclosed within defensive walls are major urban centers, palaces, trading facilities, living quarters and temples that often predate the fortifications. There is evidence here of a highly developed and elaborate courtly culture that supported learning, music and the arts. The fort uses the natural defenses offered by the landscape: inaccessible hills, deserts, rivers and dense forests. The extensive and highly engineered water harvesting structures are largely still in use today.

From the Thrilling Travel Blog

BY AMI BHAT

WHENEVER I RESEARCH A DESTINATION, THERE ARE ALways some places that I earmark as “uncompromisable,” “must visit,” “cannot avoid” kind of destinations. Kumbhalgarh, for me, was this one uncompromisable destination during my trip to Rajasthan.

It is hard to believe that you are in a desert when you pass through these hills, for they are naturally green and the cool breeze that blows along makes you realise what an apt location the Kumbha kings had chosen for their fort. The best part of this fort is that there is no restriction, and you are free to wander away from the main path to explore anything that catches your fancy. I walked along the walls to discover little watch towers, gun and cannon holes.

The walls of the fort are unusual and very scenic. They are brownish with a bit of red color. They reminded me of castles I saw in Europe. With the greenery and the lovely clouds as the backdrop, they are bound to bring out the shutterbug in you.

Unlike the other forts in Rajasthan, Kumbhalgarh Fort is devoid of guides—both real and audio. There are very few sign posts and the whole fort is kind of DIY. I frankly loved that about the fort for it gave the explorer in me a bit of satisfaction. I felt as if I was living a story. You can even explore the little tunnels near the walls. They must have been made for sentries to walk along in the night.

The entrance to the room Maharana Pratap was born in is through a flight of stairs. The room itself seemed removed from the main palace, possibly used as an infirmary or a room where mid wives were called to help out the queens. When I walked in, I realized that the room was empty and in shambles. It did not seem like a Queen’s chamber at all.

The palace is not as huge as I imagined it to be, nor as ostentatious as the Meherangarh Fort of Jodhpur. Simple and charming is how I would describe it.

Built by Rana Fateh Singh, the Badal Mahal clearly has two parts—the male chambers (Mardana Mahal) and the female rooms (Zenana Mahal). You can easily identify these sections from the decor. The Zenana Mahal has a lot of windows that would shield the women from the public eye and yet allow them to see the court proceedings.