Among the many art and photo books published in commemoration of India’s 50th year of independence, Gods, Kings and Tigers, the Art of Kotah, published by Asia Society Galleries and Harvard University Art Museums, is truly outstanding. First credit must go to the now nameless artists who created these timeless masterpieces, but the book’s editors deserve kudos for their keen eye in selecting a fascinating range of representative pieces. Superb German lithography renders every painting in vivid detail. The original pieces are part of an exhibition touring New York, Cambridge (USA) and Zurich, Switzerland, during 1997.

Kotah was a princely state of Rajpootana, an area that nowadays corresponds more or less to Rajasthan in northwest India. It was created in 1631 by Mughal decree, with whom Kotah maintained an alliance until the 1820s when it came under British suzerainty. Its economic prosperity–especially the rich farmlands–invoked envy in British inspectors.

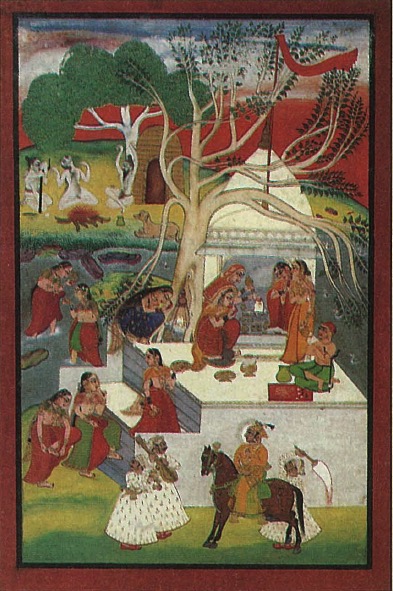

The refined court culture at Kotah was unique in the status it accorded paintings. In sharp contrast to their role at other medieval Indian courts, paintings at Kotah had pivotal roles in important royal and religious rituals in which they often were (and still are) considered to be invested with life.

Philosophically, the paintings reflect the Vaishnava Vallabha Sampradaya to which the royal family and a majority of Kotah’s Hindu population have belonged since the early 18th century. According to Vallabhacharya’s shuddhadvaita (“purified nondualism”), Divinity could reside in paintings as well as stone or metal images of the Gods. The religious practice of worshiping and lovingly caring for “live” paintings (vchitra seva) continues at Kotah today. Saint Vallabha (ca 1475-1530) said that Lord Krishna asked both Gods and their wives to “form part of the picture,” and therefore he taught that real Gods and their wives are what viewers see in the paintings.

There is a lot of Kotah art; the palace walls are covered with it inside and out, some panels reaching fourteen feet in height. The rulers successfully preserved huge stashes of paintings through the turbulent times. The present heir to the Kotah dynasty, H.H. Maharoa Brijraj Singh, maintains a large collection. The book drew upon all sources for its selection.

The paintings are mostly of court life, especially palace scenes, battles and hunts. Artists were brought along to historic meetings–much as the paparazzi follow today’s politicians–to record in detailed paintings the day’s events. So, too, were individual hunts recorded (occasionally in rather gruesome detail). Animals were a specialty of this school, especially elephants and tigers. Many festivals were depicted.

The religious art, such as seen in the gatefold opening this issue of Hinduism Today, is superb, every bit the invocation of the Divine intended by Sri Vallabhacharya. Altogether, the art is so detailed, so realistic and so successful at conveying emotion as to constitute a vivid and accurate glimpse into the life and times of early Rajasthan.

Asia Society Galleries, 725 Park Avenue New York, New York, 10021, USA. US$49.95