A call to second-generation Indians in the United States and elsewhere to do their part to help sustain our great religion and pass it on to subsequent generations

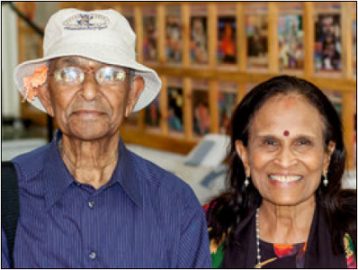

Dr. Pemmaraju Rao, devout Hindu, world expert in women’s health and passionate gardener, wrote the following article just prior to his passing in 2015.

I WAS BORN IN SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS, at a time when there were few Indians in the US. My parents were pioneers, moving here in an era when almost no Indians were here unless for scholarly research, medicine, science and education.

My father, originally a Fulbright Scholar in chemistry—one of only four chosen at that time to come from India—was an adventurous soul. At the time of my parents’ arrival in the US, my mother, was still emotionally and mentally preoccupied with her Indian family lineage and all its wit and woes. A state of shock greeted her upon arrival.

Tears come to me as I ponder their heartache as they were about to leave their ancient Motherland of India. They would be leaving the banks of the Eastern Godavari River—a cornucopia for ancient Saivism, Shaktism and Vaishnavism, the land of the gurus, sages and Gods—and landing on American soil in San Antonio, Texas, the land of cattle, cowboys, sombreros, critters and jalapenos.

I often imagine what they felt as their plane departed India, and their parents innocently waved goodbye, not knowing if they would see their children again. Somehow my parents were driven by an inner calling to go West, guided by the Divine to become Eastern pioneers in the Western world.

In looking at their lives from their arrival in the 50s to the present day, I am astonished at their courage, as well as the courage of other such Indian Hindu pioneers at the time. They would all plant the seeds of the Sanatana Dharma, which would eventually sprout into mighty trees of experience and understanding for our modern times. After an immense and ancient history, for only fifty years have Indian Hindus migrated westward. I was taught by my parents to never underestimate the power which immigrants can carry to foreign soils through their spiritual power within.

My older sister and I grew up in San Antonio, where there were really no Indian children—though later in childhood a few would arrive. We went to a Jewish kindergarten and then to public school and college before venturing out into our careers. I grew up with partial admiration as well as ridicule. I had to bear the antics of little kids yelling at me, “Holy cow!” and “Oh my Gods!”—instead of “God.” On several occasions, food and other trashed items were thrown at me with the words “Here, feed this trash to your starving relatives and family. If everyone is starving, they should eat beef!”

I deeply thank my parents that despite all this misunderstanding, they still managed to created an altar and a small temple as we grew up. They did their best to explain our Hindu tradition to us through ritual as well as in practical day to day application.

My first memories of saintly Hindu portraits were those of Sarada Devi and Ramakrishna. My mother was very close to them and would often share stories of their life and teachings. My parents would always be open to discuss each Deity, with their meaning and unique effects on our lives. They taught us that each is a ray of light within ourselves, to be worshiped outside of us to rekindle the inner lights of knowledge and willpower.

While my mother and father were far from perfect, they were able to hold on to their vision of creating a temple in San Antonio and were always able to integrate the social and cultural aspects of India with the religious. In those days they kept in contact with their other few pioneering friends around the country, and we would drive to their houses out of town for pujas, meetings and other worship services.

Pioneers: The late Dr. Rao with his wife Suvarna Rani on a visit to Kauai Aadheenam in 2007

Their Indian friends became our role models. This was important to my sister and me, for until we traveled to India years later, we had no relatives at all in our lives to relate to. Remember, in those days there were no cell phones, computers or the internet. Letters would take 21 to 30 days to reach us from India, if they arrived at all, and travel to India was no easy task as it is today. Emergency messages were sent via telegram.

My parents always found books, TV programs and films for us related to India, and signed us up for the Amar Chitra Katha cartoon books. Through these comics I learned a great deal about Hindu lore, legends, myths, facts and everything in between. As a youth I would be taken shopping. In those days, prints of Gods and Goddesses were just coming to certain East-West stores. From such materials along with other murtis and images, I would create my own temples at home with my parent’s encouragement and guidance.

My mother and father’s longing for a guru would ultimately lead them to Swami Satchidananda of the Integral Yoga Movement and also to Sri Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, founder of Kauai Aadheenam and HINDUISM TODAY. At that time they met with Gurudeva at his ashram on Kauai. Gurudeva, in his graciousness, guided them, along with Swami Satchidananda, to ultimately help create the San Antonio Hindu Temple—one of the few temples in the US in those days. My mother created, along with Gurudeva, the first Ardhanareshwara Temple. This had been a childhood dream of hers.

I have been fortunate to have the interest to be involved in many ways with Hinduism and temples in the US; but as an adult and a second-generation Indian Hindu in this country, I’ve noted time and again that most of the activities of temples and Hindu-related agendas are still largely managed and addressed by first-generation Indians—even after 64 years of migration to the US from the 1950s to the present.

Granted, I have watched many generations grow up in our Hindu religion, and I know that children, teenagers and college students are actively involved in Hindu matters. However, what still astonishes me is that, despite all the childhood exposure and the resources on Hinduism in this era, we are still lacking in the deeper continuity of help and support needed for the growing number of Hindu temples in the US.

When I go to many temples in the West, I see that most if not all adults are still first generation. It seems that this is the larger trend, even though most Hindu children and teens have had a good deal of exposure growing up. Why, I wonder, are there not as many (if not more) second-, third- and now fourth-generation Hindus participating in their traditions—like in the Jewish faith and other such traditions—especially with the explosive global awareness of Indian pop culture like Bollywood and other social influences?

I know the reasons are myriad and complex, but I cannot help wondering and contemplating these matters. Major questions that arise for me are as follows:

1. Why do we not see the second, third and fourth generations from the continuous stream of first-generation immigrants taking a more active role in funding, supervising, administering and practicing the basic and deeper aspects of Hinduism through actual temples and related manifestations, when many grew up with this knowledge?

2. Does this trend mean that a continuous wave of immigrants from India will have to lead the Hindu Renaissance around the world into the 21st century and beyond, while the second and subsequent generations fracture into their new culture?

3. What really is the future of temples and related elements of Hinduism if subsequent generations are not taking an active role?

Millions, if not billions, of dollars have been raised by first-generation immigrants for such endeavors, and they have devoted a great deal of their lives to painstaking planning, preserving, maintenance and management. After all this, I wonder if second-, third- and fourth-generation Hindus are thinking about these matters and taking them to heart.

One could speculate answers to these questions, but what I think really needs to happen is that these important concerns be addressed by second-generation Indians like me—to inspire awareness which can circulate through our own and subsequent generations. We can do this by looking at how we grew up, what needs to take place, and how we can partner with first-generation Indians to create a supportive infrastructure to support Hinduism on all levels beyond the motherland.

We need to create financial foundations and endowments, not just for Indian cultural initiatives but for the Hindu religion—supported by funding from subsequent generations. Judaism and Christianity have done this quite successfully. Such endowments can be used to support education and raise awareness about Hinduism. They can also help to support the colossal undertakings of our aging parents. Many Hindus simply are not aware of what it really takes to sustain temples and related activities, with cost, maintenance, procedure, presentation and sustenance.

As second- and now even third- and fourth-generation adults, we need to refresh and renew our own experience and knowledge of Hinduism. We can do this by taking our own measures, by meeting with gurus, Divine Mothers and others around the world, and by practicing the teachings of our original lineages to learn and relearn what we were taught and not taught growing up. We must fill the gaps in our own understanding that many of us have from growing up in a dual culture, dominated mainly by Western thought. We must also create more networks and forums for the teachings, tenets and practices of Hinduism. We can also look to new technology and social media as powerful methods of communication to truly spread a wide message around the world about the richness of Hinduism.

If we do not begin somewhere, then perhaps in the all-too-near future, temples and all related activities stand the chance of becoming archaic and dilapidated. I feel that the first-generation Hindus abroad cannot do it alone. It is going to take us all to work together. Otherwise, the pioneering efforts of our parents will go from renaissance to ruin and reversal.

We can make a difference if more of us are awakened to the importance of such an undertaking and if we work together for this common cause: to uphold a dharma that is the world’s oldest continuous tradition and practice. Are we going to let it die on the vine in the West? It is really up to us and our own inner renaissance of the heart, first and foremost, since our vines are rooted in Western soil. We need to fertilize the heart with knowledge and experience of Hinduism in order to nurture the outer manifestations of this ancient path.