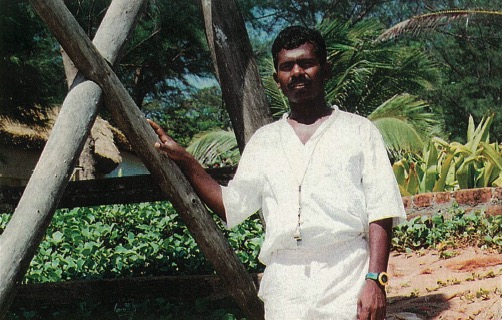

By GOWRI SHANKER, CHENNAI

Thirty kilometers South of Chennnai, Narayanan, a 28-year-old lifeguard at the five-star Fishermen’s Cove beach resort near Mahabalipuram, says, “I have saved more than 100 people from drowning to date–some prominent persons, too. One was a Russian consul, another a German diplomat. They tip me. However, I see only Kannan [the Tamil name for Lord Krishna] behind them. I use such rewards on public weal. Even yesterday we spent 200 rupees on brooms. I took 35 men and another 65 came from other parts of the city. We set to work and spruced up the main railway station in Chennai.”

Narayanan is a magnificent amalgam of social worker, athletic coach, yoga teacher, bhajan singer and exemplar of Krishna’s ideal of service. Born in the poor fishing village of Kovalam, he was cut off from higher education, but never gave up higher pursuits. “At 22, I ran 1,500 meters in three minutes and forty-five seconds, just three seconds behind the Indian national record,” recalls this Tamil rather wistfully. The would-be-famous long distance runner then adds, “As a boy, I used to visit Ramakrishna Mutt and the Vivekananda Kendra in Triplicane, Chennai. Vivekananda’s call to India’s youth, ‘For Brave Youths,’ left an abiding impression on me. I learned yoga at the Triplicane Kendra and got further training at Vivekananda Kendra at Kanyakumari. I have started a sports club attended by 45 children and named it after Vivekananda. He was as brave as he was compassionate to the downtrodden. I teach swimming, running and yoga postures. We begin with omkara dhyanam [meditation while chanting Om] and then repeat aloud ‘I am good because, Kannan, You occupy my heart. I am prepared to spend my life in the service of my motherland, upliftment of my village and my home. All are equals, for Kannan is in each one of us. I shall treat every one with love and kindness. I shall acquire the necessary skill and fight in the sports fields to win laurels for my country. I will keep my head high and never, never give up.’ Some tourists help us after learning about these potential champions. One Englishman got them T-shirts, cricket bats and balls.”

Asked if he was gaining any notoriety for his activity, Narayanan, an active abolitionist, says, “Without meaning to sound immodest, I succeeded in routing country liquor shops in my village. It is a feat, because for decades attempts by much better placed persons, even police, have failed. We banded women together under the title Sakthi Exnora, mounted a campaign, and the outraged females smashed some 20 liquor shops. Smashed they remain. It was hot news and Tamil dailies splashed it.”

Narayanan’s day begins at 5 am with “Kannan, help me do my duty well,”on his lips. Asked about the source of his devotion and passion for social service, he replied, “I owe it all to my father who passed away two years back. He was my God and guru. He always told us Ramayana and Mahabharata stories before going to bed. He dinned into us the importance of honesty and fairness.”

As for Tamil Nadu’s atheistic politicians, Narayanan feels, “Who cares? It is their philosophy. We aren’t concerned with it. Without God there is nothing here for us. We fishermen folk firmly trust in the Almighty. We feel His hands in the deep sea, calm or storm. It is not peculiar to my family alone. My sister-in-law, Jothy, says: ‘We all pray to Om Sakthi. She is there, constantly in the back of our minds even as we are engaged in domestic chores. And we pray to her at the end of the day before turning in.’ Every Saturday evening we sing bhajans in front of icons we recovered from the sea and installed near our home. In 1965, when there was a big sea erosion. A huge statue of Perumal [Lord Vishnu] was discovered. With the help of a white gentleman from Singapore we built a small temple over it and other icons later discovered in the sea while swimming. The sea here harbors many more icons. Only a few have surfaced.”

Asked how he stays cool, undazzled by the elegant, affluent tourists, their language, polish, etc., the young lifeguard asserts, “Easy. You hold on to your Kannan. He is the eternal truth. How can you be blown off your feet when He fills you?”

As for his challenges, he bemoans, “There is this massive pull that these cinema houses exert on our youth. Fighting it is not easy. When they hear me talk of Kannan, they seem impressed. They come. But they are far from regular. They find the films and seductions of the cable TV network irresistible. That is why I start with the young in my yoga school. I fare far better with them. Even if a dozen out of 45 should live out the values that are imparted here, they are bound to make a mark as good, responsible, God-fearing citizens.

Asked if he had any regrets, Narayanan laments, “I am unhappy that compliments gladden me yet. I still care for appreciation. For, has not Kannan told us to do our duty unmindful of any reward? That craving, though mild, for acceptance, has not been stamped out yet. That is my only regret.

“But I don’t mind having never become a famous athlete. There are many Narayanans in my care waiting in the wings to sprint, hop and swim their way to gold. An individual is something. A country is great. But Kannan is forever.”