By Hari Bansh Jha

IN THE 17TH CENTURY, THE REIGN of King Nagi Malla of Doti, western Nepal, was in ruin. Natural calamities, drought and cholera consumed his kingdom. Relief would come, the royal priests predicted, if he gave his daughter to the temple of Bhageshwor Mahadev. Housing facilities were immediately prepared, and the daughter of the kingdom began her life with the Gods. When the afflictions assailing the country ceased, a new tradition was born, one that has grossly degenerated and now mars the image of cultural purity that Nepal would proudly claim.

Nagi Malla could never have foreseen the injustices that would be performed centuries later in the name of his “tradition.” But his subjects were watching, and irresistible–offer a young girl to the temple, and the throes of life will cease.

Parents began giving away their own offspring as payoff for petitions to the Gods that had been fulfilled. As subsequent monarchs failed to rectify the injustice, the practice perverted as it spread through the surrounding districts. In a tragic twist, it is now common practice in western Nepal for feudal families to buy girls from poor families like the Nayak, Bist and Negi. The girls are then traded to the temple like a commodity in the hopes of a boon from the Gods.

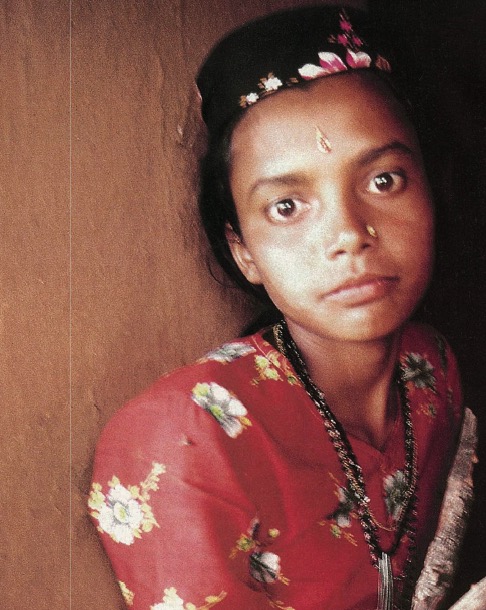

Girls thus offered are called Deuki, meaning “girl offered to God.” They are expected to engage themselves in the worship of the Gods and Goddesses. They also clean the temple utensils, collect wood and prepare food for ritual offerings. They are not considered to be ordinary servants, as their main job is to assist the priests. During festival periods, the Deuki and priests have much to do in performing the rituals and tending to devotees. But on most days of the year, there is little for a Deuki to do. And with no means to support themselves, the majority resort to prostitution. The name Deuki has become virtually synonymous with harlot.

If you ask at a temple to see the Deuki, you will be told the practice has been abolished. The muluki ain, civil code of Nepal, strictly prohibits the sale and purchase of girls for any purpose, with a stiff punishment of years of imprisonment. Nevertheless, a clandestine Deuki trade manages to thrive, and the Deuki can be found in several districts in western Nepal, including Baitadi, Darchula, Dadeldhura and Doti. The going rate for Nepalese girls these days ranges from us$400 to $500. Prominent temples where girls are offered in Baitadi district are Melauli Bhagwati, Niglasaini Bhagwati, Tripurasundari Bhagwati, Jagannath and Bhageshwor Mahadev. Baitadi claims the largest concentration of Deuki, with approximately 250. A Kathmandu UNICEF agent estimated the total number of Deuki in Nepal to be 1,000.

No way out: King Nagi Malla had the capacity to provide for his daughter and to make her life with the Deity comfortable and spiritually fulfilling. She had no wants and enjoyed a life of religious service and worship. But today’s parents do not have the means to provide for their daughter, and those who illegally trade girls feel no obligation to meet her needs once she’s at the temple. The young Deuki are thus abandoned.

They are also discriminated against. It is considered inauspicious to have a Deuki serve in your household. It is deemed unwise to marry a Deuki, as they have already been “married” to the temple. They cannot share in their parental property, as they are considered no longer to have a family. In a seeming contradiction, society regards the Deuki highly–a remnant of an earlier chaste system and the fact of their dedication to the temple. However, it is this esteem that bars them from earning wages to meet their basic needs. People are afraid of insulting or offending them, but at the same time no one offers them support. So the Deuki end up trapped, first victimized by the whim of a wealthy devotee, then crushed by the rules handed them by society.

Offered to the temples between ages five and nine years, Deuki are expected to maintain celibacy for life. It is through the offerings made to the temples that they try to scratch out their living. But such offerings are meager. Therefore, when still children, many vainly search for livelihood as a servant. As soon as they reach menarche, they are compelled to sell their body.

Many feudals consider the Deuki an exclusive source of physical entertainment and lure them to indulge their desires. They claim this as their right earned through purchasing and offering the girl. Thus, their ulterior motive for giving the girl to the temple is revealed, as most of the Deuki directly or indirectly fall in this trap. Some Deuki are even consigned to live in certain families as concubines. In such cases they do not share beds with general clients but remain as private concubines. The cases where a Deuki remains celibate are rare.

Of late, there has developed a trend for Deuki girls to travel outside their district in search of clients. According to a report from D.N. Bhatta of the Child Protection Centre (CPC) in Baitadi, such girls commonly go to urban centers like Dhangadi and Mahendranagar in Nepal and to the metropolitan cities like Bombay and Delhi in India for prostitution. This has raised serious concern over the introduction and spread of diseases like syphilis, gonorrhea and AIDS in Nepal.

Less hope: A prevalent misconception is that the Deuki system is none other than India’s devadasi system migrated and adapted to Nepal. But the history and original practice of the two systems prove this wrong. The devadasi system started long before the Deuki. In the untainted devadasi system, the girls were highly trained in India’s complex dance arts. They offered dance to the Deities daily as a part of the temple’s routine worship. They were considered an integral part of the ceremonies. By comparison, the Deuki are untrained and are not considered integral to, nor do they perform any part of the worship of the temple. They are essentially a class of assistant priests. The only commonalities are that neither system is practiced in its original purity (the devadasis of today also must resort to prostitution).

It is felt that assistance should focus on education, vocational training and annulling the superstitions that prohibit the Deuki from working and marrying. While there are thousands of Non-Governmental Organizations and several International groups working in Nepal, few have taken the problems of the Deuki seriously. The Snehi Women’s Awareness Center (SWAC) in Baitadi is an exception. Established by Krishna Kumari Poon, the Center aims to create awareness among the “socially deprived and exploited women” of western Nepal. Poon appears petite and unassuming, but she has a core of steel and a will that won’t quit. She is a rarity.

The Child Protection Center was set up in Baitadi district in 1993 with the objectives of providing shelter and protecting the daughters of the Deuki from becoming temple girls themselves. The tendency is for the daughters of a Deuki to follow their mother, thus perpetuating the tradition. According to Bhatta, Executive Secretary of the CPC, 30 girls have been admitted to the Center. There, they receive primary education and learn certain income-generating activities like making textile products and cotton garments. UNICEF of Nepal supports the CPC and the SWAC, and together they work to create public opinion opposing the Deuki system. Their commonly held hope is that this age-old custom will be eliminated by the year 2005. But with no significant involvement yet on behalf of the current government, their confidence is tenuous.

CONTACT: DR. HARI BANSH JHA, POST OFFICE ,BOX 3174, KATHMANDU, NEPAL