BY SATGURU SIVAYA SUBRAMUNIYASWAMI

Ho, ho, ho! the tree is bright with tinsel and flashing lights, a little wooden angel hovering at its top. The sweet fragrance of pine wafts through the room and around the children as they play amid the many brightly wrapped gifts nestled among soft, white cotton beneath the tree. You would think this is a Christian home, but wait. Aren’t those ladies wearing saris, and what’s that spicy scent of roasting turmeric and ginger wafting from the kitchen? Vina music fills the air, and someone answers the phone saying, “Namaste.” It’s Christmas in the ashram. While it may surprise those in other nations, Christmas is a widely-observed annual holiday in American yoga schools and Hindu cultural centers.

Everyone in America has to cope with the indisputable reality of Christmas. It’s the most touted, most advertised, most expensive, most celebratory, most exhausting holiday in the nation. Nothing even comes close. It’s the quintessential family ritual, a dramatic social and cultural extravagance and a child’s first idea of what heaven must be like and that being good pays off.

So, it will perhaps surprise readers to hear that it may be time for those following Indian spiritual traditions to stop celebrating Christmas. It’s high time we take some stands, not just pliantly fit into Western ways. I’d say Christian ways, but Christmas, it turns out, isn’t a Christian tradition at all, at least not a very old one. It wasn’t invented in Rome or Jerusalem, but in the good ‘ol USA! That’s right. Christmas is as American as apple pie. It was concocted in America, and it originally had nothing to do with baby Jesus in a manger. Now, before you reach for your keyboard to send a sizzling e-mail about how this can’t be so, let me explain.

The real myth is that Christmas began at the birth of Christ, and it was thereafter observed as a sacred family festivity until the greedy ‘ol merchants of the 20th century turned the Yuletide into a hollow hallowing, a peddler’s pageant. Those who believe this are living a fairytale, according to University of Massachusetts history professor Steven Nissenbaum’s dense, fact-filled book, The Battle for Christmas (381 pages, Knopf, $30). In his analysis, jolly old Santa Claus is more of a central figure in Christmas that Christ. He writes: “There never was a time when Christmas existed as an unsullied domestic idyll, immune to the taint of commercialism.” From its outset, he declares, Christmas has been “commercial at its very core.”

Throughout most of Christian history, there was no Christmas at all. When it did surface, it was met with Puritan disdain. Its very observation was declared a criminal offense by the Massachusetts General Court in 1659. Assailing Christmas as a pagan festival with a Christian veneer, New England Puritans were trying desperately to suppress the annual rowdiness that had evolved from ancient Germanic agricultural observances–days of excessive eating and drinking, mocking of authority, audacious begging on the streets and unrestrained invasions of the homes of the wealthy. Nissenbaum tells the tale of how this December “Mardi Gras” turned into gang violence and public riots in the early 19th century. He writes that “the Yule log, the candles, the holly, the mistletoe, even the Christmas tree [are] pagan traditions all.”

Enter a group of New York entrepreneurs and leaders. Seeking to get revelers off the streets, Nissenbaum chronicles, they led a movement to take all that wild energy and transmute it into a family-centered celebration, with special emphasis on children and presents. Charles Dickens joined the cabal, writing his classic tale A Christmas Carol, one of several fictions that fueled the movement and set the homey tone for the new holiday. Soon families started gathering at their secure hearths to share gifts, all as a counterbalance to the ruffians outside. By 1822 Santa Claus was invented, at first in a poem by Clement Clarke Moore, son of an Episcopal bishop. Saint Nick slowly morphed from a beardless sprite to become the jolly, plump patron saint of commercialism. Indeed, the immense income that stores and publishers enjoyed drove Christmas’ popularity, then as now.

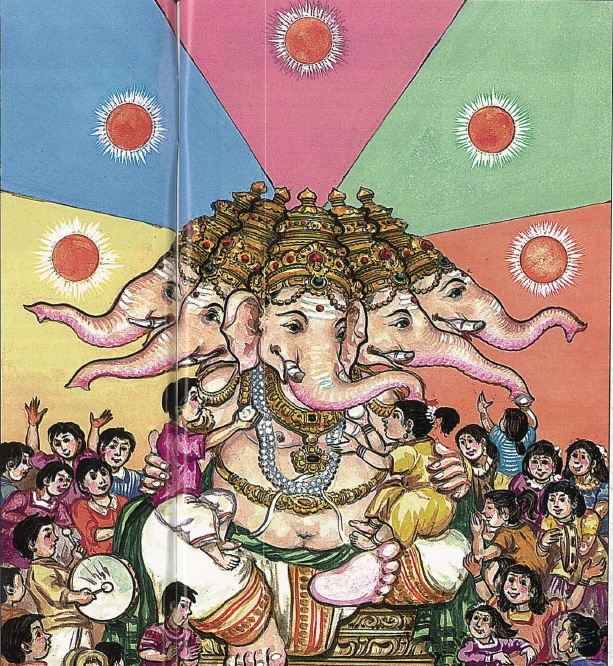

So why are ashrams and Hindu cultural halls observing an American holiday that has at its core commercial success and civic restraint? Perhaps we’re trying to fit in, trying to assure non-Hindus that “We’re not so different. We are tolerant and all-embracing.” Are we so unself-assured that we have to follow others’ culture to prove who we are? I hope not. We should not be doing this. And the fact is we have better options. Hindus could take their example from other courageous and creative peoples who have had to confront the present-day reality. Jewish families in the West turn all that energy toward Chanukah, an 8-day festival about the same time of year. Most submit to the secular gift-giving part. Creative African-Americans have created their own holiday, called Kwanzaa. Like Christmas itself, Kwanzaa was invented in America, and is now the only nationally celebrated, non-heroic Black holiday in the US. It was begun in 1966 by M. Ron Karenga to distance Blacks from the holiday’s alienation and crass commercialism. He established December 26 to January 1 to allow Black shoppers a chance to shop economically during after-Christmas sales. Millions today observe Kwanzaa and thus strengthen their culture. Hindus, too, have invented a holiday, called Pancha Ganapati, which we celebrate at our Hawaiian ashram. I propose that all ashrams, yoga schools, temples, dharma-centered societies and Hindu homes ditch the play-pretend Santa Claus and put the all-giving Lord Ganesha at the center of this seasonal holiday. Loved ones can still gather. Gifts can still be shared. Kids can still delight in the feasting and fun, and we can all still be proud Hindus when its all over.

As the season draws near, remember: we honor all religions, we don’t practice all religions. Let’s stop observing other faiths and follow the rich, celebratory heritage of India. Parents and ashram managers will find day-to-day instructions on how to make this happen on the previous page.