The call came late at night to Dr. A. Alagappan in South India from his friend, V. Shantaram, in New York. “I had a dream,” shouted a very excited Shantaram. “I was floating over the city, and beneath me I saw a building. I think it was a Christian church. The roof opened up and Lord Ganesha was sitting upon the altar.” When Shantaram said he thought he could even find the place, Alagappan rushed back from India. Together they drove around Flushing, a New York City suburb, until they came upon the same building–indeed a Christian church, now closed and for sale. It was early in the 1970s, and the sign Alagappan, C.V. Narasimhan (UN Undersecretary General) and other recently arrived Hindus had been praying for since they formed the Hindu Temple Society of North America in January, 1970. Within a few years and upon that site, they fulfilled their dream of opening the first traditionally designed Hindu temple in America. There are now dozens of such temples, and when one includes places operating as temples, but not specially built for the purpose, the number increases to the hundreds.

The story is much the same everywhere in the world that Hindus have migrated in the last three decades. India, too, is seeing hundreds, if not thousands, of new temples being built, especially in expanding metropolises such as Delhi, Mumbai, Calcutta and Chennai. So, too, have countries of the 19th century Hindu diaspora–Fiji, Trinidad, South Africa, Kenya, Surinam, etc.–experienced their own flurry of temple construction in the last two decades. The new Subramaniya Temple in Nadi, Fiji, for example, is by far the largest in the country, and the first built in traditional Indian style. Thiru V. Ganapati Sthapati designed it, and many other of the new temples as well. Two Indian communities have taken the lead in this fervor of construction, Gujaratis and Tamils.

There were, it must be said, many early Hindu emigrants from India in the 1960s and ’70s who had no plans to found temples in the West. Indeed, they fully intended to leave their religion back in India and become “Englishmen” or “Americans” and, perhaps, return to India and their Hindu roots after retirement. Most didn’t give this decision much thought until their kids reached six or seven years of age. Suddenly they realized that without some expression of Hinduism in their adopted home, their children would grow up without their religion, or even convert to other religions. Thus began a truly massive push for temples in the late ’70s, following the example set by New York’s Ganesha Temple and early projects in the UK.

Refugee Hindus from Uganda in 1971 and Sri Lanka in 1983 settled in dozens of countries around the world and built places of worship in Britain, Switzerland, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Germany, France, Australia, Canada and elsewhere. These refugees were a cross-section of Hindu society, and on the whole, more religious than the earlier group of professionals.

Temple development has, of course, not been without its struggles. At first there were no full-time priests, so brahmin members of the emigrant community performed the worship. By the early ’80s the larger temples were bringing full-time priests from India. Money has been a major problem, even in communities with many high-income professionals. In numerous cases huge loans were taken out, requiring paralyzing monthly payments. But once this initial stage is past, such as for the Balaji Temple in Pittsburgh, an abundant income funds both expansion in America and projects in India.

The original objective–to train children in the rich spiritual culture of Hinduism–has been a challenge, for they live between two cultures, but Hindu student groups have formed to promote their heritage and its values in modern times. Many organizations have successfully engaged the youth, notably the BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha, under the guidance of Sri la Sri Pramukh Swami Maharaj, who has even recruited Western-born Gujaratis into his 600-strong order of monks.

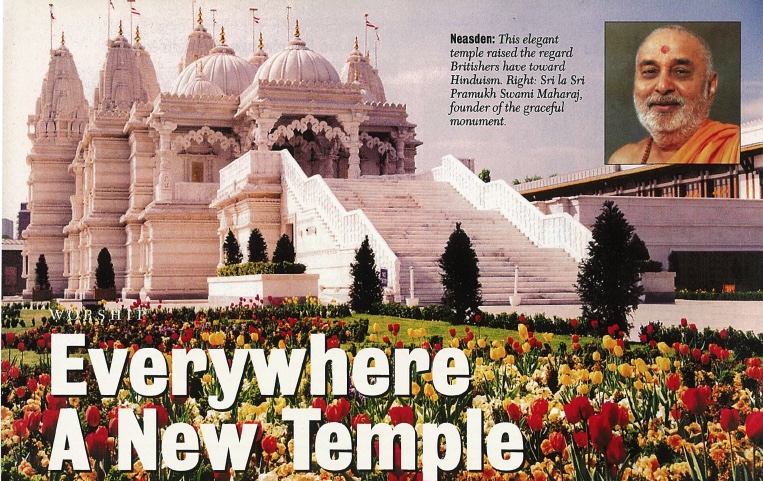

Take the massive 70-foot-tall, 195-foot-long Swaminarayan Mandir in Neasden, UK. Tremendous community support brought 1,100 devotees of Pramukh Swami and 450 craftsmen together to labor three years creating a 102,018 square-foot complex. Kids were deeply involved, selling hundreds of thousands of aluminum cans to raise funds. Today, amidst acclaim by UK parliamentarians and religious leaders, the Mandir and adjacent cultural hall are the center of life for the youth, a place where they are taught the arts and scripture.

The trend has changed, at the close of the 20th century, from simple meeting halls to full-fledged palaces. Structures built in the ’80s are renovating, expanding, adding higher towers. New structures in the planning stages are twice the size of those built before. The senior emigrant community has matured as well. Money is abundant now. Most have paid for their homes, and university for their children is no longer a concern. Now, as retirees seeking the blessings of the Gods for a good birth next time around, they have loosened their purse strings considerably.

Extraordinary is the 1900s religious fever. While interest has often waned in other faiths toward their spiritual edifices, Hinduism is in revival, witnessed by great temple renovation and building. In the ’30s the millionaire Birla family erected the graceful Lakshminarayan Mandir in the middle of New Delhi. A massive restoration of South India’s Chidambaram temple in the ’80s saw 65 million rupees spent to renovate the 40-acre complex. Pilgrimage to the popular Sabarimala temple in Kerala–with its arduous jungle trek–is so monumental that it now significantly impacts the state’s economy and environment. Annual total commercial activity generated by that one pilgrimage is estimated at an astounding US$880 million. Sixty million pilgrims visited Sabarimala in 1995, resulting in plans for new hotels and better roads. Tirupati, the world’s wealthiest religious institution after the Vatican, with 35,000 pilgrims daily, has similar expansion plans. Another sign of resurgence is the 1,000-year-old Thanjavur temple–rescued from the jungle earlier this century. Designated a World Heritage Site by the United Nations in 1987, it was excavated, restored and worship has started again. Similarly, Angkor Wat in Cambodia is being rescued.

Hindus aren’t alone in spiritual renaissance. Europe’s and Russia’s indigenous Pagan temples are returning, and the Hawaiians are clearing temple grounds that have languished for a hundred years. For the first time, as this issue demonstrates, a temple carved completely in India will be erected in America. Public acceptance to all this is profoundly positive, giving courage to Hindus and to all the Earth’s indigenous faiths.