By Choodie Shivaram

It was afternoon when I visited the Iraivan temple carving site–the silence was so perfect and divine. There was music in the air–the sounds of chirping birds and the chiseling of stone blended in perfect harmony. Here, 18 kms outside Bangalore, the stones of Iraivan Temple are being sculptured and prepared for shipment to the serene surroundings of Kauai, continents away. The cobra-infested site–an arid piece of land strewn with huge granite blocks eight years ago–is a beautiful sight now, with finished stones neatly on display. It is, in fact, an entire village with 75 workers, their wives and children. The land has been provided for the duration of the project by Sri Balagangadharanatha Swami. He and Sri Tiruchi Maha Swamigal have been vastly instrumental in blessing and guiding the project.

The carvers, called silpis, are presently working on the granite blocks, giving them shape and expression. As I took a tour around the work area, I sensed there was something different here. I had seen silpis working at other temple sites–smoking beedis and chatting as they chiseled. Not here. All were silently working, concentrating on the fine curve their chisel had to create–no beedis, no cigarettes, no spitting, no chatting and no noise! Project manager Jiva Rajasankara of Malaysia informed me that most of the silpis had given up smoking and drinking and had even turned vegetarian.

I asked 28-year-old Lokesh why this site was different. He said, “I have been in this job of sculpting temples for over 10 years now. But this is the only place where I have learned devotion. There seems to be some magic here. Whatever our problems may be at home, they seem to vanish when we report to work. My mind is totally concentrated on my stone all day. ”

Almost all the craftsmen I spoke to voiced a similar opinion, proclaiming that they have become spiritual after coming here. Jiva, his wife Kanmani and their two sons conduct classes for the carvers in Hinduism, devotional singing and hatha yoga. Ahimsa philosophy, nonviolence, guides the workplace: anyone found fighting or hitting their wives or children will be discharged. About 30 of the silpis are married; half of them have brought their wives and children to the work site. Free housing is provided.

I found the carvers indebted to Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami for the religious environment and innovative benefit schemes such as pensions and health care. “There is no better job than to work for a highly revered employer,” said Manikandan, one of the most skilled ornamental carvers. “I foresee a beautiful temple. The ornate carvings here are so immaculate. How gifted I am to be actually doing this for Gurudeva.”

The silpis begin their day with a small prayer and hymn singing at a granite replica of the crystal Siva Lingam in Kauai. After smearing holy ash on the forehead, they start work at 7:30am sharp, and go ’till 6:30pm, with an hour’s break for lunch.

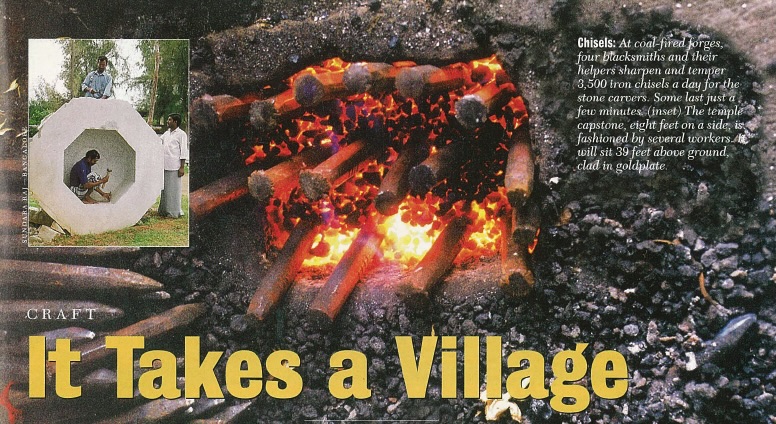

The work is tedious. Everything is done by hand. One objective of the project is to preserve the ancient methods of this craft, and that means no power-driven stone working machines. It requires 865 days for two men to carve one of the ornate lion pillars from a ten-ton granite block. Even the small decorative tridents that form part of the temple railing require a full month. A single wrong strike of the hammer could spoil thousands of hours of work. One measure of the effort is the 3,500 chisels sharpened daily by the blacksmiths. Some of the 60 shapes and sizes last just two or three minutes before dulled. Project manager Jiva estimates up to 50% of the granite blocks delivered to the site “ends up as chips and dust.” Chidambaram Pillai is the resident artisan, assisted by Sundaramachari and C. Thangavelu. They work under the direction of Ganapati Sthapati and together supervise a team of 10 ornamental sculptors, 41 stone carvers, 4 blacksmiths and 17 helpers. Eight years underway now, the carving is expected to be completed in another seven.

C. Subramaniam told me, “I have never seen such fine work. It is very challenging to do this. Here they give us the time to do detailed work without any rush. Only in this way can we bring out the best in our work.” Rahamatullah, a Muslim, has been with the project since the beginning. So has his uncle, Naina Mohammad, who attends the morning prayers, and has adopted the temple’s motto. He said, “For me, it is ‘One God, One World.’ When we put all the carved stones together, this will be a beautiful temple that will astonish the world.”

Will they leave if someone offers to pay them more I queried? “No,” says 72-year-old Ganapathychary, who has been a silpi for over six decades. “We may get more money elsewhere, but this environment will not be there. There’s some power in this place, which guides us. Occasionally, a few workers do leave, only to return a few days later.”

The silpis told me that unlike other workplaces, the artisans have the opportunity to learn and grow professionally here. Seventeen-year-old Babu, who joined as a blacksmith, within six months had graduated to become a stone worker. “There is ample scope to develop one’s skills. We do not encounter the problem of a superior suppressing the junior. Even a novice can learn the skill and excel here,” avers Thangavelachary.

In eight years of hard work on the Iraivan temple, the workers seem to have collectively developed an affection and reverence for the project. To them, it’s not just a stone they are carving for remuneration; it is God’s work. They feel they are an instrument infusing life into something inanimate. Carvers told me they would work here even if they were paid nothing–that sums up the spirit behind their loving toil in India on a project destined for Hawaii.