BY SWAMI PARAMTATTVADAS

A BAPS Disciple of Guru Pramukh Swami Maharaj and Mahant Swami Maharaj

A presentation of the Swaminarayan philosophy, which was recently recognized as an authentic school of Vedanta, in line with yet distinct from the philosophies of Shankara, Ramanuja, Madhva, Nimbarka, Vallabha and Chaitanya

This is the story of a rare occurrence in Hindu sacred literature, the appearance of a distinct school of Vedanta. It has been hundreds of years since such a happening, and the Hindu world celebrates. In this Educational Insight, the monks of the Swaminarayan Fellowship share a summary of their philosophy and the amazing events that gave birth to this philosophical revelation, a story inspired by Pramukh Swami Maharaj, captured in a five-volume Sanskrit commentary by his disciple Swami Bhadreshdas and reconciled with academic authenticity by Swami Paramtattvadas. While the subject is technical and complex, readers will find it fascinating to step into this theological realm and watch as history unfolds before our eyes.

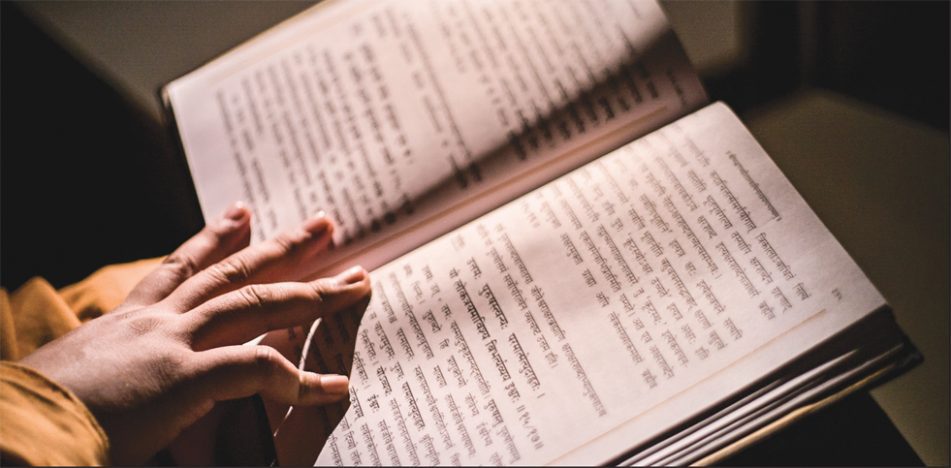

The practice of earnest inquiry has long been embedded in Hindu devotional life and intellectual discourse. For example, the Shvetashvatara Upanishad opens with the following series of questions: “What is the cause? Is it Brahman? From where are we born? By what do we live? And on what are we established? Governed by whom, O you knowers of Brahman, do we live in pleasure and pain, each in our respective situation?” Such lofty questions represent a heartfelt quest to know ourselves, the world around us, and the supreme power by which everything is enlivened, sustained and can be ultimately transcended for eternal freedom and bliss. This perennial seeking of spiritual knowledge and liberation, when grounded in the sacred authoritative texts of the Brahmasutras, Upanishads and Bhagavad-Gita—collectively known as the Prasthanatrayi—is known as the classical system of Indian thought called Vedanta.

Vedanta as Darshan: The Vedas are considered the highest scriptural authority in Hinduism. Vedanta, as the name indicates—Veda + anta (literally “end”)—refers to the conclusive essence of the Vedas that is enshrined in their final set of treatises, the Upanishads. Together with the Brahmasutras and the Bhagavad-Gita, which further clarify and consolidate the teachings of the Upanishads, these three sets of scriptures comprise Vedanta Darshan.

Vedanta is classified as a darshan because it is described as the art of seeing. Darshanis derived from the Sanskrit verb-root d®ß, to see,1 which in a deeper sense means to perceive or know.2 Darshan thus literally means seeing, and can also mean “that by which one can see,” i.e., the eyes. In a fuller, cognitive sense, a darshan is a system of wisdom and practice that helps one know, experience and realize the truth; it provides a vision and insight into the reality of ourselves, the world and God. Of the six ancient systems of Indian philosophy, classically called the Shad-Darshan, Vedanta is the most prominent and widely practiced today.

Darshans within Vedanta: Within Vedanta Darshan itself there emerged several individual schools of thought, each one also identified as a darshan. A tradition arose in which each school established itself according to the teachings of the Prasthanatrayi; only then would it be accepted as an authentic school of Vedanta. Hence, exponents from each of the Vedanta schools formulated commentaries on the Brahmasutras, Upanishads and Bhagavad-Gita, providing their own interpretations of the complex texts to demonstrate that their doctrines were grounded in the original revelatory sources, thus validating their school of thought.

A Distinct School of Vedanta

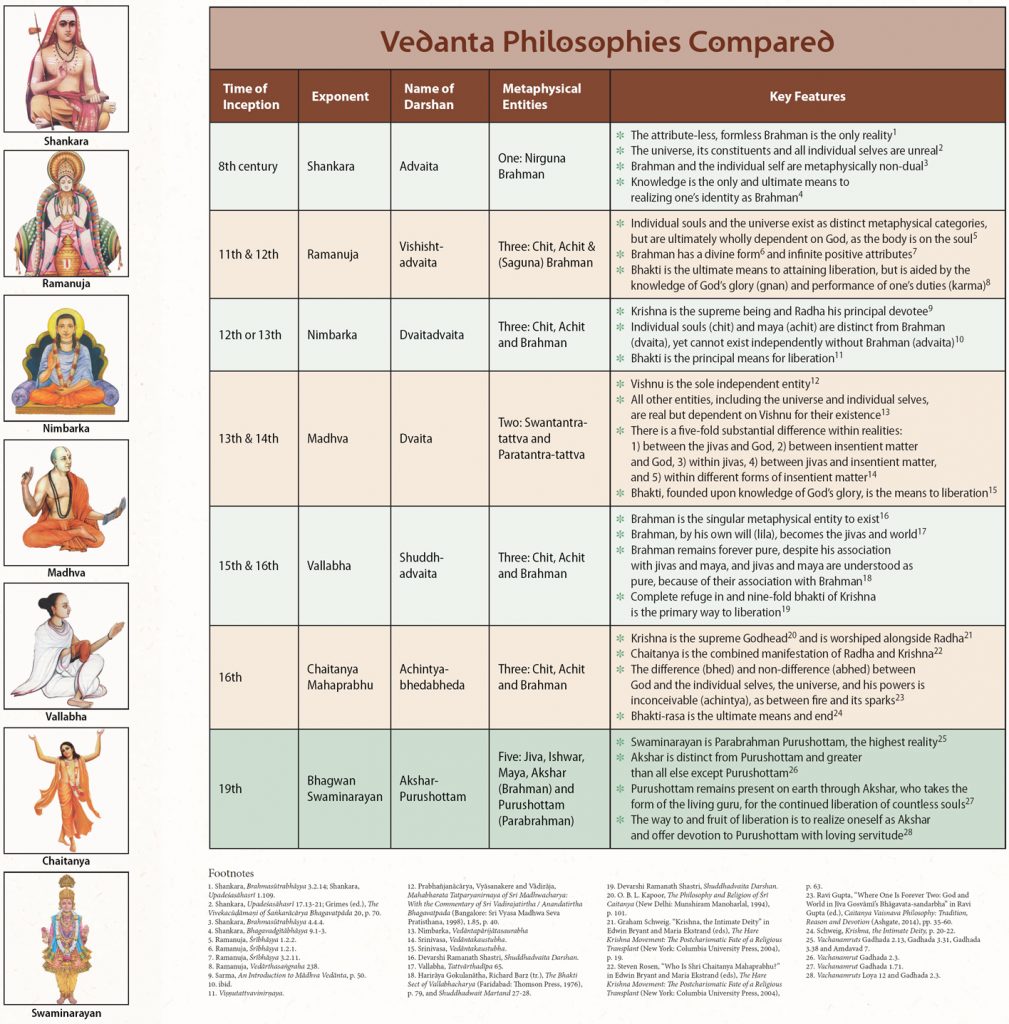

Hinduism has been blessed with magnificent scholars over the centuries who have written commentaries on the Prasthanatrayi and established or consolidated their respective schools of Vedanta. Among these, some of the most notable exponents and the distinct darshan they each propounded include the following: Shankara’s Advaita Darshan, Ramanuja’s Vishishtadvaita Darshan, Madhva’s Dvaita Darshan, Nimbarka’s Dvaitadvaita Darshan, Vallabha’s Shuddhadvaita Darshan, and Chaitanya Mahaprabhu’s Achintyabhedabheda Darshan.3 Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, as revealed by Bhagwan Swaminarayan, is positioned within this rich tradition of Vedanta darshans.

In line with this hallowed tradition, His Holiness Pramukh Swami Maharaj, the previous spiritual guru of BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha, instructed Bhadreshdas Swami in 2005 to write Sanskrit commentaries on these sacred texts. Bhadreshdas Swami, one of the leading scholars of our time, had already been studying Swaminarayan texts, Sanskrit and the classical schools of Indian philosophy for over 24 years under the inspiration and guidance of Pramukh Swami Maharaj. With his guru’s blessings and his own scholarly expertise and tremendous hard work, Bhadreshdas Swami completed the mammoth task in less than three years, offering the five-volume, 2,000-page classical commentaries to Pramukh Swami Maharaj before the end of 2007. Titled Swaminarayan Bhashyam, these commentaries provide a word-by-word explanation and elaboration of the Brahmasutras,ten principal Upanishads and the Bhagavad-Gita according to the teachings of Bhagwan Swaminarayan.

Bhadreshdas Swami subsequently composed the Swaminarayan Siddhanta Sudha—a classical vadagrantha, or didactic treatise that offers a systematic and comprehensive exposition, justification and defense of the Akshar-Purushottam Darshan’s theological and philosophical principles. He offered this work to His Holiness Mahant Swami Maharaj in 2017. Together, these classical texts have helped Akshar-Purushottam Darshan be recognized among scholarly communities in India and abroad as a distinct, authentic school of Vedanta.

Scholarly Impressions

The scholarly works of Bhadreshdas Swami have received worldwide critical acclaim from eminent experts of Indian philosophy, theology, Indology, Sanskrit and other related fields, where they have both praised the literary value of the texts and recognized Akshar-Purushottam Darshan as a distinct school of Vedanta.

The late Professor N. S. Ramanuja Tatacharya, former Vice-Chancellor of the prestigious Rashtriya Sanskrit Vidyapeeth at Tirupati and award-winning researcher at the French Institute of Pondicherry, was one of the most senior and renowned scholars in India on Navya-Nyaya and Ramanuja Vedanta. He writes: “In the past, eminent ācāryassuch as Śkara, Rāmānuja, Madhva and Vallabha have put forth immense effort to establish Advaita, Viśiṣṭādvaita, Dvaita and Śuddhādvaita, respectively. They have done this by composing commentarial texts based on the Prasthānatrayī according to their own teachings and corresponding schools of thought…. Sadhu Bhadreshas’ complete commentary on the Prasthānatrayī, entitled the Svāminārāyaṇabhāṣyam, is exemplary of this continued tradition. The work presented by Sadhu Bhadreshdas is a monumental exposition of a novel philosophy and is a priceless contribution to the world.”4

Professor Tatacharya further explains, “Although some of the principles of Śaṅkara, Rāmānuja, Madhva and others of the Vedānta tradition are similar to one another, there are many principles… that are characteristic of these schools of thought, and hence, distinguish them from one another. The Svāminārāyaṇa tradition is also to be understood as being distinct for these same reasons.”5 Furthermore, “Although Swaminarayan did not himself compose commentaries on the Upanishads, Gita, or any other sacred texts, he often cited and offered his interpretations on them in his discourses. These interpretations of the verses were distinct from those offered by ācāryas including Śaṅkara and Rāmānuja, who preceded him and offered their own interpretations according to their respective schools of thought. Swaminarayan’s expositions were unprecedented and novel; thus, many were unaware that his sampradāya has its own distinct philosophy.”6

The late Professor Radhakrishnan Bhatt, former Head of Sanskrit Research and Publication at Karnataka State Open University in Mysore, deduced from the Brahmasutra Swaminarayan Bhashyam: “By studying this commentary, one concludes that the Svāminārāyaṇa sampradāya and the Akṣara Puruṣottama Siddhānta is an independent tradition that is based on the ancient Vedic principles. The tradition’s principles greatly differ from Rāmānuja’s Viśiṣṭādvaita, Vallabhadāsa’s Śuddhādvaita and the philosophy of Madhva, Nimbārka and other Vedanta darśana.”7

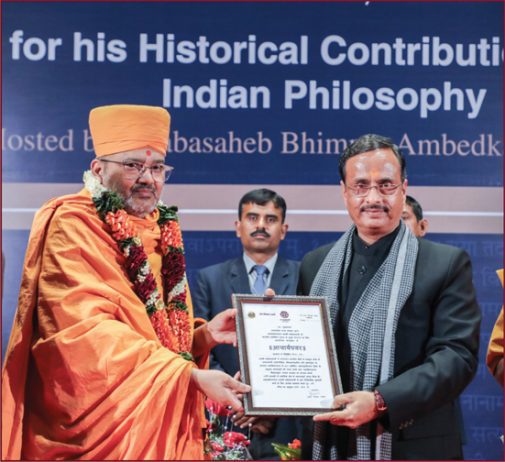

On 31 July 2017 in Varanasi, India, prominent members of the Shri Kashi Vidvat Parishad,8 after studying the Swaminarayan Bhashyam commentaries and the Swaminarayan Siddhanta Sudha, concluded that “Sadhu Bhadreshdas is an acharya and a contemporary commentator in the lineage of commentators on the Prasthanatrayi” and “it is in every way appropriate to identify Shri Swaminarayan’s Vedanta by the title of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan. Therefore, we all unanimously endorse that this Akshar-Purushottam Siddhanta revealed by Parabrahman Swaminarayan is a Vedic siddhanta that is distinct from Advaita, Vishishtadvaita, Dvaita and all other schools.” In commemoration of this historical contribution to Vedanta Darshan, the Shri Kashi Vidvat Parishad presented a written proclamation attesting to the above, which they presented again, as an engraved copperplate, in New Delhi on 13 August 2017.

At the 17th World Sanskrit Conference at British Columbia University in Vancouver, Canada, in 2018, Bhadreshdas Swami presented a succinct introduction to Akshar-Purushottam Darshan in the inaugural session, outlining its salient features and roots in the Prasthanatrayi. The assembled scholars welcomed the lucid presentation and applauded the Swaminarayan Bhashyam and Swaminarayan Siddhanta Sudha as a major contribution to the world of Sanskrit literature. Further sessions also saw various academic papers presented on Akshar-Purushottam Darshan and a panel discussion of leading Sanskrit scholars of Western and Indian academia on the Swaminarayan Siddhanta Sudha.9

This 16-page educational Insight offers a brief overview of this distinct school of Vedanta called Akshar-Purushottam Darshan.

Footnotes

1. Gajanan Balkrishna Palsule, A Concordance of Sanskrit Dhātupāṭhas (Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 1955), p. 186.

2. Sayanacharya, Mādhavīyā Dhātuvṛitti [a treatise on Sanskrit roots based on the Dhātupāṭha of Paṇini], Dwarikadas Shastri (ed.) (Varanasi: Prachya Bharati Prakashan, 1964), 1.707, p. 286.

3. Surendranath Dasgupta, A History of Indian Philosophy, Vols 1-5 (London: Cambridge University Press, 1922-1955).

4. N.S. Ramanuja Tatacharya, “Sādhu-Bhadreśadāsa-Viracita-Prasthānatrayī-Svāminārāyaṇa-Bhāṣyam-Saṅkṣipta-Paricayaḥ,” Journal of The Oriental Institute, 66.1-4 (September-December 2016 to March-June 2017), 280.

5. ibid.

6. ibid, 280-281.

7. N. Radhakrishnan Bhatt, “Brahmasūtra-Svāminārāyaṇabhāṣyam,” Journal of the BAPS Swaminarayan Research Institute, 1.1 (2018), 179.

8. The Shri Kashi Vidvat Parishad is a highly esteemed, time-honored council that has been formed for the protection of Vedic dharma. It adjudicates on matters of Vedic teaching and research, carrying authority throughout India. The council comprises some of the most illustrious scholars in India from a wide array of fields, including grammar, logic, poetics, philosophy and literature.

9. The 17th World Sanskrit Conference: Conference Programme, pp. 27, 32 & 33.

The Divine Life of Bhagwan Swaminarayan

Bhagwan Swaminarayan is Parabrahman Purushottam, the highest existential reality. He manifested on Earth in human form on 3 April 1781 in the tiny village of Chhapaiya, near Ayodhya, in north India. He chose to be born into a modest, pious family, to mother Bhakti and father Dharmadev. They named him Ghanshyam, though he would be known by many names throughout his life, including Neelkanth, Sahajanand Swami, Shrihari and Shriji Maharaj.

Ghanshyam brought great joy to his family and everyone who met him. But even as a child, it was obvious that he was no ordinary human. He sent animals into trances, overcame evil beings with his miraculous powers, and often revealed his higher purpose on earth—to liberate countless souls from their ignorance and grant them the eternal bliss of God. Once he brought a catch of fish back to life, teaching the fisherman that ahimsa is the highest ethical code, and inspiring him towards a life of non-violence and compassion.

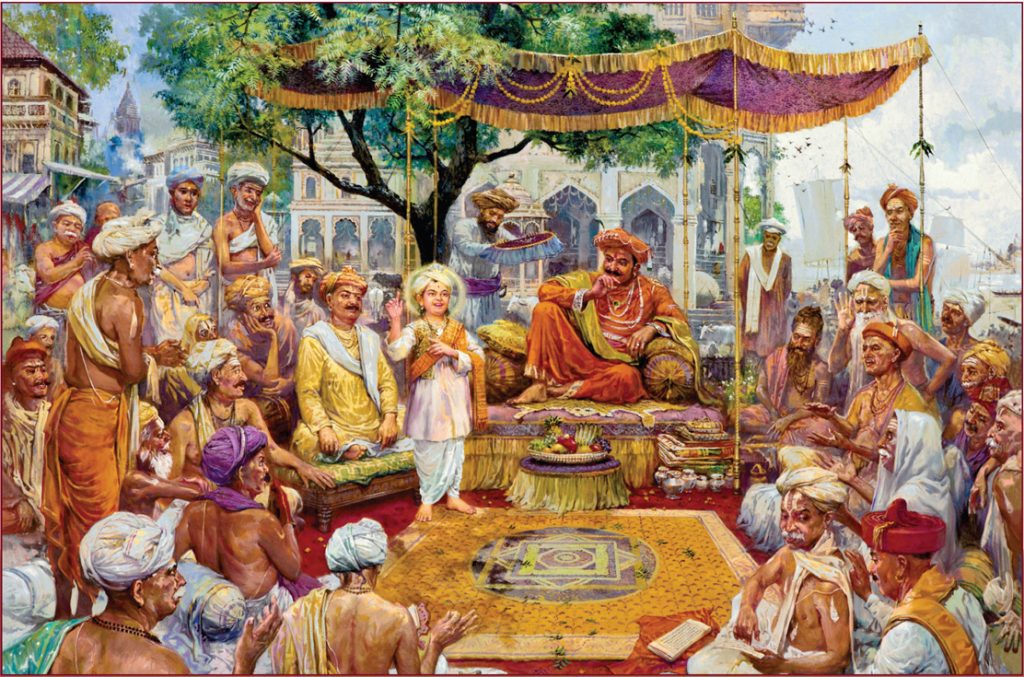

Dharmadev tutored Ghanshyam in Vedic literature, the Puranas, the epics, and other key texts of Hindu wisdom. Ghanshyam’s divine genius meant he quickly mastered the sacred scriptures. When he was only 10, he won a debate with the pundits of Varanasi, employing incisive scriptural testimony and irrefutable logic.

On 29 June 1792, having served his parents to their final breath, 11-year-old Ghanshyam renounced his home and family to embark upon a spiritual journey of epic proportions. For seven years and almost 8,000 miles, Ghanshyam traveled the length and breadth of India, crossing into Nepal and Tibet (China), and through Myanmar and Bangladesh. During this time, he came to be known as Neelkanth. Barefooted and alone, carrying no maps, no food and no money, he crossed raging rivers, faced ferocious animals, and survived the freezing winter of the Himalayas. Wearing nothing but a loincloth around his waist, he trekked to Kedarnath, Badrinath and Gangotri, navigating the treacherous mountainous terrain at heights of more than 19,000 feet and enduring temperatures that regularly plummeted to -20° C (-4° F). He even reached Mount Kailash and Lake Manasarovar in Tibet.

During the monsoon of 1793, Neelkanth arrived in Pulhashram, near Muktinath, in Nepal. For 68 days, Neelkanth stood on one leg in yogic posture, performing austerities in torturous weather to bless the world with his purity and goodness. By the age of 14, Neelkanth had mastered ashtanga yoga.

Wherever Neelkanth traveled, he blessed the land and liberated spiritual aspirants along the way. His journey was a story of courage, kindness and enlightenment.

On 21 August 1799, Neelkanth arrived in western Gujarat, from where, as Sahajanand Swami, he went on to establish the Swaminarayan Sampradaya in 1801 at the age of 20. One of his first works was to introduce a powerful new mantra for daily worship. It often sent people into samadhi, a trance-like state where they enjoyed divine visions, including seeing Sahajanand Swami as the supreme reality. Its widespread popularity led to Sahajanand Swami becoming synonymous with that mantra, Swaminarayan.1

Bhagwan Swaminarayan spent the next 28 years traveling around Gujarat, ushering in many religious and social reforms and spearheading a spiritual awakening. He preached against superstitions, addictions and violence, he served the poor and needy, and he championed the welfare of women, children and the underprivileged. For example, he admonished malpractices such as sati (widow immolation) and dudhpiti (female infanticide), encouraged education and established places of worship for all women.

His charismatic life, profound teachings and works of edification attracted followers from all over India and a spectrum of religious and cultural backgrounds. During his lifetime, he amassed an estimated fellowship of more than two million, and ordained around 3,000 swamis, 500 of whom were of the highest monastic order, called paramhansas. They worshiped him as God.

Bhagwan Swaminarayan garnered the respect of British officials and Christian clergy, including the Governor of Bombay, Sir John Malcolm, and the Bishop of Calcutta, Reginald Heber. Bishop Heber writes about Bhagwan Swaminarayan in his journal of 1824-25: “His morality was said to be far better than any which could be learned from the Shaster [scriptures]. He preached a great degree of purity, forbidding his disciples so much as to look on any woman whom they passed. He condemned theft and bloodshed; and those villages and districts which had received him from being among the worst, were now among the best and most orderly in the provinces.”2

Bhagwan Swaminarayan’s moralizing impact on the lawless populace of that time led the British to gift him some land in Ahmedabad to build a temple. Between 1822 and 1828, Bhagwan Swaminarayan consecrated six majestic temples. He also inspired the creation of scores of scriptural texts, including the Vachanamrut [see sidebar on p. 48-49], and thousands of bhajans. He was hailed as a patron of the arts and education, while also reviving several Hindu institutions of devotion and festivity, but devoid of the indiscipline and indignity that had crept in over centuries of negligence or misinterpretation.

When Bhagwan Swaminarayan visibly left this Earth on 1 June 1830, he had already become an epochal figure of public stature and adoration. Henry George Briggs, a notable 19th-century British historian and traveler, wrote in his famous The Cities of Gujarashtra in 1849, “As the announcement of his death was winged, one wail—loud, piercing and bitter—rang throughout Gujarat, upon the signal calamity which was believed to have befallen the country.”3 Manilal C. Parekh, a Gujarati Anglican theologian and historian, wrote: “Indeed, so remarkable are the life and work of Swami Narayana that it is no exaggeration to say that these constitute a very important chapter not only in the religious life of India, but in the history of Religion in general. In him, Hinduism approximates to the Perfect Form of Religion as in few others, and his life, work and the movement he led have few parallels in the entire range of history.”4

1. The Svāminārāyaṇa-Siddhānta-Sudhā explains at pp. 8-9 that in the Swaminarayan mantra, Swami refers to Akshar, and Narayan refers to Purushottam. In other words, Swaminarayan is synonymous with Akshar-Purushottam and thus an encapsulation of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan.

2. Reginald Heber, Narrative of a Journal through the Upper Provinces of India from Calcutta to Bombay 1824-1825 (London: John Murray, 1828), Vol. 3, p. 29.

3. Henry George Briggs, The Cities of Gujaráshtra: Their Topography and History; Illustrated in the Journal of a Recent Tour; with Accompanying Documents (Bombay: James Chesson, 1849), p. 239.

4. Manilal C. Parekh, Shri Swami Narayana: A Gospel of Bhagavata Dharma or God in Redemptive Action, 3rd edn. (Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1980), p. ix.

The Philosophy: Akshar-Purushottam Darshan

Sources: God, Guru and Scripture

Bhagwan Swaminarayan was Parabrahman Purushottam. He himself revealed Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, which is an exceptionally significant feature of this darshan. God himself is describing what he is and how to realize him. Indeed, when he manifested on earth just over two hundred years ago, he is showing who he is, making the revelation especially gracious, direct and powerful.

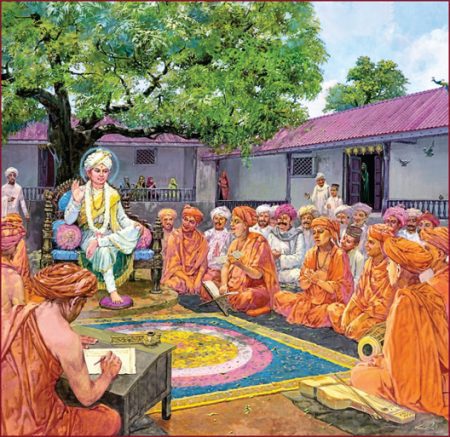

During his manifestation on earth, Bhagwan Swaminarayan delivered extensive discourses in which he articulated the doctrines of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan. These discourses were meticulously documented by four of his most senior and learned swamis. This compilation came to be known as the Vachanamrut. Bhagwan Swaminarayan’s teachings from the Vachanamrut thus form one of the most important sources of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan.

According to a central Hindu belief, it is imperative to seek a qualified guru to understand such scriptural wisdom. For example, the Mundaka Upanishad instructs:

Tadvijñānārthaṃ sa gurum evābhigacchet

samidhpaṇiḥ śrotriyaṃ brahma niṣṭham |

“To realize that [higher knowledge], imperatively go, with sacrificial wood in hand, to only that guru who is the knower of the true meaning of revealed texts, who is Brahman, and who is firmly established [in God].”

That is, only the guru who is the living form of Brahman (“brahma”) and fully established in Parabrahman (“niṣṭham”) can have the most direct and perfect realization of scriptural truths (“śrotriyaṃ”), making him the most qualified and able to convey them.1 To be precise, according to the Bhagavad-Gita at 4.34, such gurus are not only knowers of the revealed truth (“jñāninaḥ”), but direct seers (“tattvadarśinaḥ”) of it.2

In Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, the guru is the human embodiment of Brahman on earth and is referred to varyingly by such names as Sant, Ekantika Bhakta or Satpurush.In being a pure and complete vessel of Parabrahman, through whom Parabrahman Purushottam reveals himself and leads devotees to himself, the Aksharbrahman Guru serves as the perfect medium to correctly explain the meaning of the scriptures. Thus, Bhagwan Swaminarayan proclaims the guru throughout the Vachanamrut as the exclusive authoritative guide to scriptural knowledge and spiritual realization. For example, after delivering an exceptionally important discourse on the nature of God, in particular alluding to himself as Purushottam, Bhagwan Swaminarayan appends his address with the following caveat: “However, such discourses regarding the nature of God cannot be understood by oneself even from the scriptures. Even though these facts may be in the scriptures, it is only when the Satpurush manifests on this Earth, and one hears them being narrated by him, that one understands them. They cannot, however, be understood by one’s intellect alone, even from the scriptures.”3

As perfect vessels of Parabrahman Purushottam, the life and teachings of the Aksharbrahman Gurus also serve as vital sources of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, including, for example, the Swamini Vato of Gunatitanand Swami. The Siddhanta Alekhwritten by Pramukh Swami Maharaj,4 a succinct creedal treatise of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, is another example of an exceptionally valuable and venerable source of theological revelation.

The Swaminarayan Bhashyam and Swaminarayan Siddhanta Sudha also have a prime place within the corpus of primary sources for Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, having been commissioned, guided and ratified by gurus Pramukh Swami Maharaj and Mahant Swami Maharaj.

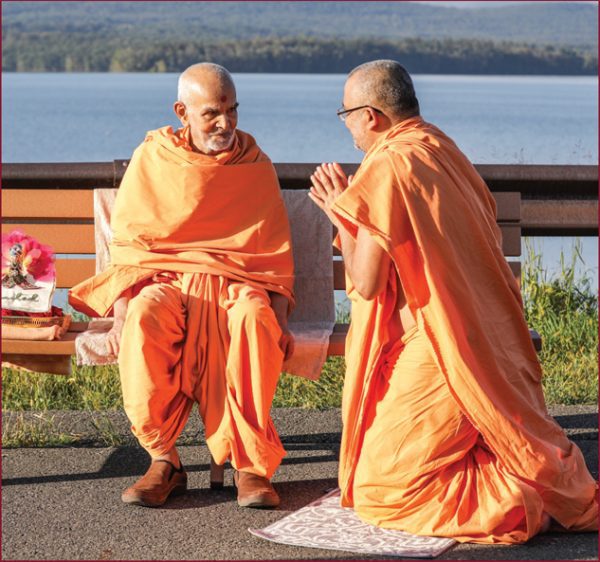

It is through this revelation of Parabrahman Purushottam Bhagwan Swaminarayan as received through the Aksharbrahman Gurus and the scriptures they explain that one is able to properly understand Akshar-Purushottam Darshan. Currently, that guru is Mahant Swami Maharaj.

Ontology: The Five Eternal Entities

Ontology is the study of being; the philosophical inquiry into the nature of reality and existence. A discussion of any classical school of Vedanta Darshan invariably begins with such an inquiry into its basic entities of existence or realities: Which metaphysical entities does it accept as real? The answer to this fundamental question more often than not reveals much about the school’s basic premises and beliefs. For example, Shankara posited a singular, attribute-less Brahman, which necessarily requires the visible world to be unreal and illusory.5 In contrast, Ramanuja argued for a Brahman that qualifies sentient and non-sentient entities, allowing for the world to be real as well as individual souls to be distinct from God.6 Madhva, on the other hand, propounded a Brahman that is radically distinct and independent from all else.7 Uniquely, Bhagwan Swaminarayan revealed that there are five metaphysical entities that are eternal and forever distinct from one another:

1. Purushottam (also known as Parabrahman)

2. Akshar (also known as Aksharbrahman & Brahman)

3. maya

4. ishwar

5. jiva8

Strikingly, he posited two Brahmans—Aksharbrahman and Parabrahman. How can this be? And what implications does this have for such a system of Vedanta? The ensuing discussion based on Bhagwan Swaminarayan’s teachings and the Prasthanatrayicommentaries will help explain some key aspects of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan while affirming its position as a distinct and authentic school of Vedanta.

Akshar and Purushottam in the Vachanamrut

Akshar and Purushottam are the two ontological entities expounded throughout the Vachanamrut, which covers every aspect of their nature, function, relationship, means of knowing, etc. Below are excerpts from two separate discourses in which Bhagwan Swaminarayan reveals the essence of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan.

In Vachanamrut Loya 12, when outlining varying degrees of faith, Bhagwan Swaminarayan explains that a person with the highest level of resolute faith “realizes that countless millions of brahmands [planetary realms], each encircled by the eight barriers, appear like mere atoms before Akshar. Such is the greatness of Akshar, the abode of Purushottam Narayan.” He then immediately states: “One who worships Purushottam realizing that [Akshar] to be one’s own form can be said to possess the highest level of resolute faith.”

Bhagwan Swaminarayan reiterates this doctrine in Vachanamrut Gadhada 2.3. This time, when defining brahmagnan, he uses Brahman for Akshar and Parabrahman for Purushottam. He first describes Brahman as “the cause of all,” as its “support,” and that which “pervades all through its indwelling powers.” When describing Parabrahman, Bhagwan Swaminarayan expounds:

“Transcending that Brahman is Parabrahman Purushottam Narayan, who is distinct from Brahman, and is the cause, the support and the inspirer of even Brahman.”

Bhagwan Swaminarayan thus clearly distinguishes Aksharbrahman from Parabrahman, and clarifies Parabrahman as superior to Aksharbrahman.

Bhagwan Swaminarayan goes on to add in the same discourse:

“With such understanding, one should develop a oneness between one’s jivatma and that Brahman, and worship Parabrahman while maintaining a master-servant relationship with him. With such understanding, brahmagnan also becomes an unobstructed path to attaining the highest state of enlightenment.”9

This is the essence of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, which is comprehensively described and established throughout the Vachanamrut.

Akshar and Purushottam in the Upanishads

Brahmagnan is synonymous with brahmavidya, which is the focus of the Upanishads. For example, the Mundaka Upanishad, which forms a part of the Atharva Veda, lauds brahmavidya as the “highest”10 and “foundation of all forms of knowledge.”11 It then defines it explicitly in the following verse:

Yenākṣaraṃ puruṣaṃ veda satyaṃ provāca tāṃ tattvato brahmavidyām ।

“Brahmavidya is that by which Akshar and Purushottam are thoroughly known.”12

The Swaminarayan Bhashyam substantiates this definition by citing profusely from the entire Mundaka Upanishad and other Prasthanatrayi passages. For example, the distinction and relationship between Akshar and Purushottam is evident in the Mundaka Upanishad at verse 2.1.2. It states:

Puruṣaḥ… akṣarāt parataḥ paraḥ //

“That Purush’ [i.e., Purushottam] is… greater than

Akshar, which is greater than others.”

The Swaminarayan Bhashyam explains that Akshar is described here as greater than all other beings and things—jivas, ishwars, maya, even liberated souls—exceptPurushottam, thus confirming the mutual distinction and relationship between Akshar and Purushottam.13 Bhagwan Swaminarayan also repeatedly describes Purushottam’s supremacy in relation to Akshar, often using the adjective aksharatit (transcending Akshar),14 demonstrating that Akshar is the highest benchmark by which to understand Purushottam, but one which he still surpasses. In other words, it is only after understanding the greatness of Akshar that one can truly appreciate the greatness of Purushottam. That is, it is essential to know both Purushottam (Parabrahman) andAkshar (Aksharbrahman) to master brahmavidya.

In further support of the two types of Brahman, the Swaminarayan Bhashyam cites from the fifth chapter of the Prashna Upanishad. Here, in reply to the question posed bySatyakama pertaining to the after-life, Pippalada states:

Etad-vai satyakāma paraṃ cāparaṃ ca brahma yad-aumkāraḥ।

“That, O Satyakama, which is the syllable of Aum, is verily the higher and lower Brahman.”)

The dual classification of “higher” and “lower” confirms the metaphysical distinction between “para” Brahman, i.e., Parabrahman, and “apara” Brahman, i.e., Aksharbrahman. This distinction between the two is especially evident when the fruit of meditating on Aumis described in the same verse as attaining “either” of them.15

Akshar and Purushottam in the Bhagavad-Gita

The two entities Akshar and Purushottam are evidently established in the Bhagavad-Gitaby these two very names. Indeed, the eighth chapter of the Bhagavad-Gita is titled “Aksharbrahman Yoga,” while the fifteenth chapter is titled “Purushottam Yoga.” Both chapters hold key discussions about Akshar and Purushottam. For example, Arjuna asks in the opening verse of the eighth chapter,

Kim tad brahma (What is Brahman?)

Krishna replies simply: Aksharam brahma

(Akshar is Brahman.)16

The eighth chapter then goes on to describe the glory of Akshar as a divine place entered by those who practice brahmacharya and are without desire, and as proclaimed by the knowers of the Vedas.17

In the fifteenth chapter, the Bhagavad-Gita succinctly and clearly describes the nature of Purushottam and its distinction from Akshar and other entities. As the Swaminarayan Bhashyam explains, there are two types of beings in the world: kshar and akshar. All those bound by maya are kshar, i.e., subject to change; whereas the one who is unchanging—forever beyond maya—is Akshar. The Supreme Being is distinct from and superior to both kshar and Akshar; he is called Paramatma and known in the world and Vedas as Purushottam.18

Akshar and Purushottam in the Brahmasutras

The Brahmasutras is an esoteric text of aphorisms that elucidate Brahman. It seeks to clarify, systematize and harmonize the meaning of the Upanishads, hence its focus of study is also “brahmavidya” or “brahmagnan.” The first aphorism, “Athā’to brahmajijñāsā,” holds the key to unlocking the various schools of Vedanta. Every acharya, while describing Brahma according to his own particular system, deconstructs brahmajijñāsa in largely similar ways, that is, to mean “the desire to know Brahman,” where brahma in the Sanskrit compound is in the singular. The Swaminarayan Bhashyam commentary on this aphorism provides a remarkable new interpretation, claiming that the brahma in brahmajijñāsā denotes not just Parabrahman but also Aksharbrahman; that is, taking brahma not in the singular but in the dual case. This makes the subject of brahmagnanboth Aksharbrahman and Parabrahman, also known as Akshar and Purushottam. The Swaminarayan Bhashyam substantiates this interpretation by citing several passages of the Upanishads and Bhagavad-Gita, a few of which have been mentioned above.19

In this way, some of the fundamental and key distinguishing doctrines of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan are established and articulated in the teachings of Bhagwan Swaminarayan and the Prasthanatrayi scriptures.

Mukti and Sadhana

The goal and fruit of all darshan is liberation from the ravaging influence of maya so that one is free of all suffering and can experience supreme bliss.

In Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, such liberation, or mukti, is more than a state of being maya-free and released from the pain and limitations of the incessant cycle of births and deaths. It is a new, higher spiritual state—indeed, the highest, perfect spiritual state—that is enriched by the complete realization of Parabrahman Purushottam. It entails not merely the dispelling of ignorance, but the positive receiving of Aksharbrahman’s qualities, so one is perfectly faultless and fulfilled, absolutely free of all worldly desires and ego, and forever engrossed in unhindered devotion to God while experiencing his limitless, unending bliss. Bhagwan Swaminarayan calls this preeminent spiritual state being aksharrup or brahmarup (“like Akshar or Brahma”).20 It is described in the Bhagavad-Gita as brahmi sthiti21 or being brahmabhuta.22

This state of liberation is of two types:

Jivan-mukti, meaning “living mukti,” is attaining and experiencing the state of aksharrupwhile alive, in this very body.

Videh-mukti is liberation after death, enjoying the superlatively blissful darshan of Purushottam in Akshardham along with the personified form of Akshar and other liberated souls (muktas).

While the location of the experience might be different, the experience of bliss for both muktas is the same.

The way to mukti is called sadhana. Bhagwan Swaminarayan explains this extensively throughout the Vachanamrut, as do the Aksharbrahman Gurus through their teachings and lives. Primarily, it entails the complete loving association of the Guru through thought, word and deed.23 This incorporates Ekantika Dharma, a four-fold system of praxis (spiritual endeavors) defined by Bhagwan Swaminarayan as comprising the following:

1. dharma: leading a righteous life by observing the moral codes of the scriptures;

2. gnan: realizing oneself to be the atma, distinct from the body;

3. vairagya: being dispassionate towards worldly pleasures; and

4. bhakti: offering selfless devotion to God while realizing his greatness.

This sadhana is summarized in the sadhana mantra provided by Mahant Swami Maharaj: Akṣaram aham Puruṣottamadāso’smi. It is chanted by devotees daily, reminding them to offer devotion to Bhagwan Swaminarayan as Purushottam—albeit through his most accessible form, the current Aksharbrahman Guru—after qualitatively realizing oneself as Akshar by spiritually and lovingly associating with that same Aksharbrahman Guru. This is the essence and foundation of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, by which all of its doctrines are illumined and consummated.

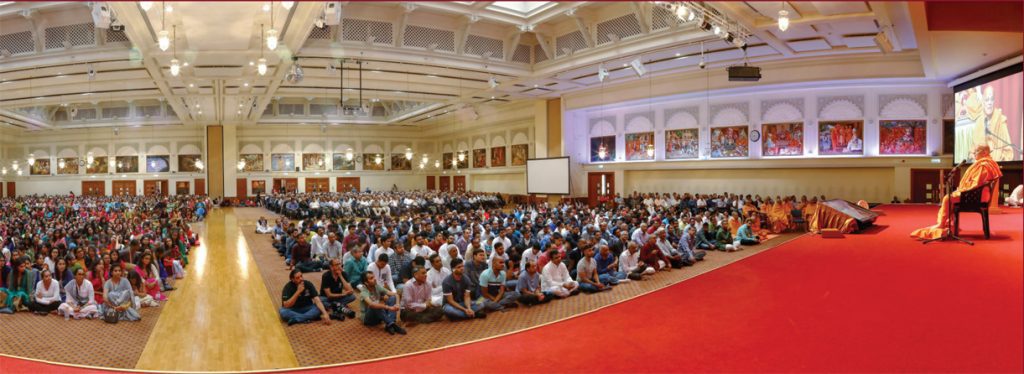

Living Darshan

Darshans are a way of life, not just a topic of philosophical debate. Indeed, the success of any system of thought is how it is applicable to and implemented in daily life. True to this, the Akshar-Purushottam Darshan is a living tradition being practiced by hundreds of thousands of devotees around the world today. It is lived out in their daily acts of devotion, such as the personal nitya puja with which they each start their day, the religious markings they apply, the two-stranded kanthi of tulsi beads they wear around their necks, the darshan they enjoy of the murtis at mandirs, at home or online, the arati they sing, the discourses and bhajans they listen to, and much more. All these are reflective of and imbued with the doctrines of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan. Indeed, in thousands of mandirs, homes and hearts, there thrives the daily worship of Parabrahman Purushottam Bhagwan Swaminarayan as exemplified by the Aksharbrahman Gurus.

This vitality and flourishing of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan is possible because of the living guru. The Swaminarayan Siddhanta Sudha concludes with this very thought, that the principles expounded at length in the text are lived and experienced by devotees in their daily lives through the association of the Aksharbrahman Guru. In fact, it stresses, there are many devotees in the Swaminarayan community who have been and are perfectly fulfilled by their absolute conviction in Akshar-Purushottam Darshan. They are unburdened by any lack of knowledge of the scriptures, because they have the direct association of the guru, which exceeds millions of such texts. Indeed, it asserts, nothing is greater than the blessed association of the Aksharbrahman Guru through whom devotees experience the supreme love, bliss and inner fulfilment of Parabrahman Purushottam Bhagwan Swaminarayan here and now.24

Footnotes

1. Sadhu Bhadreshdas, Muṇḍakopaniṣat-Svāminārāyaṇa-Bhāṣyam 1.2.12, pp. 253-256.

2. Sadhu Bhadreshdas, Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā-Svāminārāyaṇa-Bhāṣyam 4.34, p. 110.

3. Vachanamrut Gadhada 2.13.

4. This can be found as an appendix, “Theological Principles of BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha: Creedal Statement by Pramukh Swami Maharaj,” in Swami Paramtattvadas, An Introduction to Swaminarayan Hindu Theology (Cambridge University Press, 2017), pp. 321-325.

5. John A. Grimes, The Vivekacūḍāmaṇi of Śaṅkarācārya Bhagavatpāda: An Introduction and Translation (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2004), verse 20, p. 70.

6. S.S. Raghavachar, Vedārtha-Saṅgraha of Śrī Rāmānujācārya (Mysore: Sri Ramakrishna Ashrama, 1968), verse 117, p. 90.

7. Deepak Sarma, An Introduction to Mādhva Vedānta (London & New York: Routledge, 2016), p. 50.

8. Vachanamrut Gadhada 1.7 and Vachanamrut Gadhada 3.10.

9. See also Bhadreshdas Sadhu, “Brahmajñāna in Akṣara-Puruṣottama Darśana and Viśiṣṭādvaita Darśana,” Brahmavidyā: The Adyar Library Bulletin, 81-82 [Śrī Rāmānuja’s Sahasrābdi Volume] (2017-18), 471-488.

10. Sadhu Bhadreshdas, Muṇḍakopaniṣat-Svāminārāyaṇa-Bhāṣyam 1.1.5, pp. 236-237.

11. Ibid, 1.1.1, p. 232.

12. Ibid, 1.2.13, pp. 256-257.

13. Ibid, 2.1.2, pp. 258-261.

14. Vachanamruts Gadhada 1.31, Gadhada 1.42, Gadhada 1.51, Gadhada 1.66, Gadhada 1.78, Sarangpur 5, Gadhada 2.13, Gadhada 2.18 and Gadhada 2.31.

15. Sadhu Bhadreshdas, Praśnopaniṣat-Svāminārāyaṇa-Bhāṣyam 5.2, pp. 214-216.

16. Sadhu Bhadreshdas, Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā-Svāminārāyaṇa-Bhāṣyam 8.3, pp. 173-177.

17. Ibid, 8.11, pp. 182-185.

18. Ibid, 15.16-18, pp. 314-316.

19. Sadhu Bhadreshdas, Brahmasūtra-Svāminārāyaṇa-Bhāṣyam 1.1.1, pp. 3-12.

20. For example, Vachanamrut Gadhada 1.21 and Vachanamrut Gadhada 2.20.

21. Sadhu Bhadreshdas, Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā-Svāminārāyaṇa-Bhāṣyam 2.72, pp. 68-69.

22. Ibid, 18.54, pp. 360-361.

23. Vachanamrut Vartal 4.

24. Sadhu Bhadreshdas, Svāminārāyaṇa-Siddhānta-Sudhā, p. 459.

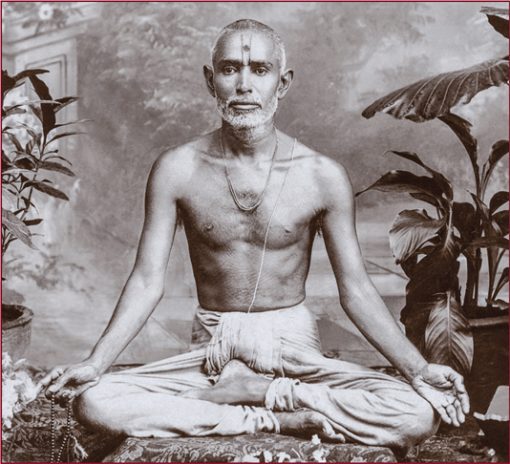

One Monk’s Tale of Sacrifice & the Guru’s Grace

Bhadreshdas Swami (b. 1966) is the author of Swaminarayan Siddhanta Sudha and the five-volume Swaminarayan Bhashyam commentaries. He was barely 14 when His Holiness Pramukh Swami Maharaj initiated him into the BAPS monastic order in 1981. The ensuing 38 years of spiritual tutelage under gurus Pramukh Swami Maharaj and then Mahant Swami Maharaj, as well as guidance from senior swamis, engaged Bhadreshdas Swami in a rigorous program of devotion, austerities, studies and academic research. Above all, by the gurus’ grace and blessings, he developed into one of the world’s leading scholars of Vedanta and an internationally acclaimed expert of the Swaminarayan Hindu tradition.

But Bhadreshdas Swami’s journey has been far from straightforward. In 2007, while writing the Swaminarayan Bhashyam commentaries, a flash flood struck the village of Sarangpur, in India, where he stayed. Within minutes, his basement study was completely submerged, ruining his entire library and more than 2,500 pages of research notes he had painstakingly compiled. These notes contained all of his arguments and definitions of key philosophical terms that would form the framework of the commentaries he was writing. Despite attempts to salvage the mud-sodden pages, they were lost forever. Shocked and desperate, he called guru Pramukh Swami Maharaj, who was traveling in America at the time. Pramukh Swami Maharaj lovingly reassured him, “Everything that you weren’t supposed to write has been washed away. Now when you write, Bhagwan Swaminarayan and our gurus will write everything through you.” What had been a colossal task before—Pramukh Swami Maharaj had requested all five volumes of the commentaries to be ready by December of 2007, in time for the centennial celebrations of BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha—seemed near impossible now. But with the grace and blessings of his guru and his own indomitable faith, Bhadreshdas Swami returned to writing. Within six months, working 18 to 20 hours a day, the commentaries were ready.

Bhadreshdas Swami followed this magnum opus with another mammoth undertaking, the Swaminarayan Siddhant Sudha—a classical treatise that offers a systematic and comprehensive exposition, justification and defense of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan. Together, these works of philosophical genius have led to a string of qualifications and accolades making Bhadreshdas Swami one of the most decorated Indian scholars of our time.

The historical significance of Bhadreshdas Swami’s work can hardly be overstated. His Sanskrit opus is unique because: 1) it is the first such commentarial work in a school of Vedanta for 150 years; 2) it is the first complete set of commentaries on the Prasthanatrayi (the Brahmasutras, Upanishads and Bhagavad-Gita) by a single acharya in 1,200 years; 3) and it is the first time ever that a single acharya has authored both a complete set of Prasthanatrayi commentaries together with a vadagrantha of their darshanic tradition.

Bhadreshdas Swami’s monumental work has been widely recognized and critically acclaimed by eminent scholars around the world, including from over 150 universities and academic institutions in India, Europe and North America. They hail his work as being exquisitely lucid, fascinatingly original and profoundly compelling, recognizing him as a modern-day “Acharya” in line with Shankaracharya, Ramanujacharya, Madhvacharya, Nimbarkacharya and Vallabhacharya.

Bhadreshdas Swami remains immersed in study, research, writing, teaching and devotion. He is currently working on a classical commentary of the Vedas, treatises on Yoga Darshan and Samkhya Darshan, and an agamic treatise on devotional practices according to Akshar-Purushottam Darshan. Bhadreshdas Swami continues to travel the world engaging with scholars and delivering academic presentations. He teaches Nyaya, Vedanta, History of Indian Philosophy, and classical Indian music to swamis at the BAPS Swaminarayan Sanskrit Mahavidyalaya in Sarangpur.

Yet for all his accomplishments and the honors heaped upon him, Bhadreshdas Swami unfailingly attributes all the credit to his gurus. He says, “Whatever I have written, it has only been possible through the blessings, love and constant guidance of guruhari Pramukh Swami Maharaj and Mahant Swami Maharaj. Whenever I sit down to write, I pray to them and I feel their presence, as if they are writing through me. So I have no hesitation in acknowledging—without their wish, none of this would have been possible.” Bhadreshdas Swami thus opens his commentary on the Brahma-Sutras with the acknowledgement that his work is “by the guru’s grace; for the guru’s grace.”1

For a detailed account of Bhadreshdas Swami’s extraordinary journey in writing the Swaminarayan Bhashyam commentaries through the grace of his gurus, see pages 54-57 of the April/May/June 2014 issue of HINDUISM TODAY.

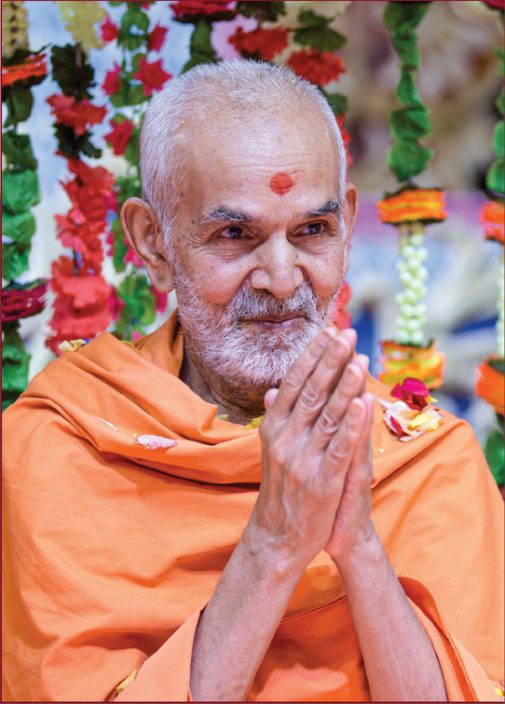

A Living Guru Lineage

Akshar-Purushottam Darshan was revealed and established by Bhagwan Swaminarayan during the early 19th century. It has been protected, sustained and advanced till today by an unbroken succession of Aksharbrahman Gurus—the Guru Parampara. Paramparaliterally means “one after the other,” a succession. The Halayudhakosha, a famous Sanskrit lexicon, defines the term sampradāya as “gurukramah,” a lineage of successive gurus. In the BAPS Swaminarayan tradition, this succession has continued unabated for over 200 years, from Gunatitanand Swami (1784-1867), Bhagatji Maharaj (1829-1897), Shastriji Maharaj (1865-1951), Yogiji Maharaj (1892-1971) and Pramukh Swami Maharaj (1921-2016), to the present guru, His Holiness Mahant Swami Maharaj (b. 1933). The BAPS Swaminarayan fellowship believes that today Bhagwan Swaminarayan wholly dwells in and works through Mahant Swami Maharaj.

Having a living guru with perfect realization ensures that the tradition, while steadfast in its timeless core beliefs, remains fresh through an active process of reflection and interpretation, by which theological insights and spiritual practices are tested, protected and transmitted. In fact, the very definition of sampradaya, even if translated as “tradition,” points both ways—not just to the past but, ironically, also to the future. When elaborating upon the second half of the Bhagavad-Gita verse 4.34: Upadekṣyanti te jñānaṁ jñāninas tattvadarśinaḥ. (“Enlightened seers of truth will preach that knowledge to you.”), the Swaminarayan Bhashyam is keen to point out the use of the future tense in the verb upadekṣyanti (will preach) and the plurality in the nouns jñāninaḥ (knowers) and tattvadarśinaḥ (seers of truth). The verse thus affirms the succession of Aksharbrahman gurus who will continue to transmit this revelatory knowledge to generations of seekers indefinitely into the future.

The Vachanamrut

The primary sacred scripture of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya is the Vachanamrut. It is a collection of 273 discourses delivered by Bhagwan Swaminarayan between 1819 and 1829. These discourses were meticulously documented and compiled by four of his most learned and senior disciples—Gopalanand Swami, Muktanand Swami, Nityanand Swami and Shukanand Swami—and later presented to him for review and personal verification (see, for example, the mention in Vachanamrut Loya 7). This compilation came to be known as the Vachanamrut, which literally means ‘immortalizing ambrosia in the form of words.’

The text is divided into ten sections, based on the various villages and towns in which the discourses were delivered. The sections are chronological in order and named as follows: Gadhada 1, Sarangpur, Kariyani, Loya, Panchala, Gadhada 2, Vartal, Amdavad and Gadhada 3, with an additional section including discourses from Amdavad, Ashlali and Jetalpur. Each individual discourse is also called a “Vachanamrut,” and these are arranged chronologically and numbered sequentially within each section. VachanamrutVartal 11, for example, is the eleventh recorded discourse delivered by Bhagwan Swaminarayan in the town of Vartal.

Ingeniously, each Vachanamrut opens with an introductory paragraph meticulously describing the setting of the assembly in which the discourse was delivered. Even at the risk of sounding repetitive, the compilers invariably recorded the date, the place, and a mention of the audience seated in the assembly. In many instances, they also noted the time of day and described the clothes and adornments worn by Bhagwan Swaminarayan. In some instances, they even described the seat upon which he was seated and the direction in which he was facing. All this lends considerable historical authenticity to the sacred scripture.

In literary style, the Vachanamrut is highly dialogical and didactic, with most discourses taking the form of a question-and-answer session, where either Bhagwan Swaminarayan asks the questions or members of his audience do, sometimes at his urging. Even if he begins a sermon unprompted, he would sometimes question his own explanation to confirm if his audience had understood him correctly or to anticipate and answer opposing views in advance. More often, though, his aspiring seeker-followers, ranging from senior monks to lay farmers, would be braced with questions from their current readings of Hindu texts or their own personal application of those teachings. As Bhagwan Swaminarayan would answer, sometimes a series of follow-up questions or counter-questions would ensue as they probed for further clarity or refinement in their understanding of his teachings. This orality (speaking) and reciprocal aurality (listening) between Bhagwan Swaminarayan and his disciples situates the Vachanamrut in the ancient Upanishadic tradition of a guru-disciple dialogue.

Bhagwan Swaminarayan spoke in the local language of Gujarati, presenting complex concepts in simple, lucid terms, drawing extensively on popular stories from the Puranasand epics, and employing analogies and day-to-day examples. He also cited profusely from the Upanishads, Bhagavad-Gita, Bhagavata Purana, and various other authoritative Hindu texts.

Most importantly, the Vachanamrut is accepted within the Swaminarayan tradition as the primary revelatory scripture by which its doctrines are established and articulated. This abiding status of the Vachanamrut is grounded on the distinctive belief of the devotees that Bhagwan Swaminarayan, as the self-manifestation of Purushottam, is both the source and subject of divine knowledge comprised within it. In other words, in the Vachanamrut, it is God talking about God.

What Are the Five Eternal Entities?

Jivas

Jivas are distinct, individual souls, indivisibly minute in size and innumerable in quantity. Each one is bound by maya, which shrouds the jiva’s radiant self that is composed of existence (sat), consciousness (chit) and bliss (anand). They are doers of good and bad karmas, and experiencers of the fruits of those karmas.

Ishwars

Ishwars, by the will of Purushottam, are assigned various tasks of creation, sustenance and dissolution within a particular brahmand (planetary realm), of which there are countless millions. Compared to jivas, ishwars have greater power, knowledge and lifespan, but like the jivas, ishwars, too, are shrouded by maya since the beginning. Compared to Akshar and Purushottam, however, ishwars are utterly powerless. Like jivas, ishwars also are doers of good and bad karmas, and experiencers of the fruits of those karmas.

Maya

Maya is characterized by the three gunas—sattva, rajas and tamas. It is eternal while continually mutating. As an instrument of Purushottam, it constitutes the base substance from which this material world is formed. It also forms the ignorance in the form of “I-ness” and “my-ness” that shrouds jivas and ishwars, causing them to be bound in the incessant cycle of birth and death. Akshar and Purushottam are eternally and entirely untouched by maya and transcend it, yet they also pervade it and control it. Maya is the only non-sentient (non-living) entity of the five; the other four are all sentient (living).

Akshar

Akshar, also called Aksharbrahman and Brahman, is distinct from and subordinate only to Purushottam; it transcends jivas, ishwars and maya. Like Purushottam, it is one, eternal and a sentient entity. It is forever divine, replete with infinite redemptive virtues, devoid of all qualities of maya, and forever faultless. The form, qualities, powers, etc., of Akshar are dependent only on Purushottam. By the eternal will of Purushottam, Akshar is the cause, support, controller, indweller and shariri (“soul”) of the entire insentient and sentient creation.

Although Akshar is one entity, it serves in the following four ways:

1. Abode: Akshar takes the form of the divine abode of Purushottam, known as Akshardham. There is only one such Akshardham; it is eternal and forever transcends the three gunas of maya. Only liberated souls who have become aksharrup (“like Akshar”) are able to enter it.

2. Sevak: Akshar also serves Purushottam in Akshardham as an exemplary devotee. Like Purushottam, Akshar has a divine human-shaped form complete with two arms and other features. He remains forever engrossed in the worship of Purushottam and is the ideal for the liberated souls worshiping Purushottam in Akshardham.

3. Divine Light: This is a form of ethereal space, known as Chidakash. It is extremely radiant, and is an all-pervading form of Akshar that permeates, envelopes and upholds the infinite brahmands.

4. Guru: Akshar manifests in human form as the Guru, with Purushottam, in every brahmand. He is the eternal and complete vessel of Purushottam. Through his divine association, he establishes in jivas and ishwars the highest level of resolute faith in Purushottam and elevates them to the state of aksharrup so that they may offer perfect devotion to Purushottam. He thereby grants them eternal liberation from the bondage of maya, releasing them from the cycle of birth and death and ultimately granting them an eternal place in Akshardham where they experience the highest bliss of Purushottam. Purushottam remains forever manifest through an unbroken succession of such Aksharbrahman Gurus, by whom he grants liberation and devotees experience his highest bliss. While this succession continues forever, the path to ultimate liberation remains open through only one such Guru at any one time.

Purushottam

Purushottam, or Parabrahman, can be understood through the following four aspects of his being:

1. Sarvopari (“supreme”): Purushottam is the supreme being, the highest existential reality; one and unparalleled. He is forever beyond time and space—he is eternal and all-pervading—and forever limitless in his power, knowledge, splendor, bliss and virtues. He is always completely free of any defiling qualities of maya, hence “nirguna,” and is replete with countless superlatively excellent auspicious qualities, hence also “saguna.” He is the cause of and master of all avatars; he is the avatari. An avatar manifests when, by his special wish, he pervades an ishwar for a particular task, but that avatar is, by its very being, distinct from Purushottam. Purushottam is also distinct from, transcendental to and the lord of even Akshar.

2. Karta (“doer”): Purushottam is the ultimate all-doer. Nothing can happen without his will. In fact, he is the shariri (“soul”) of the entire world; just as a soul is to an otherwise inert body, Purushottam indwells, enlivens, supports and governs everything, including the mayic world, jivas, ishwars, liberated souls, even Akshar. He is both the efficient cause (agent) and material cause (substance) of the world, thus its ultimate creator, sustainer and dissolver. While permitting jivas and ishwars to act according to their free will, and inspiring them to will, know and do, he is also the dispenser of the fruits of their karmas.

3. Sakar (“with form”): Purushottam is eternally human in form yet fully divine. In his abode, Akshardham, he is seated on a divine throne in his eternally divine, extremely radiant and human-shaped youthful form, complete with two arms and other human-like features. There he is worshiped by the personal form of Akshar and infinite brahmic-bodied, aksharrup liberated souls. Without relinquishing this transcendental distinct form, Purushottam pervades the infinite brahmands through his immanent form by his divine powers.

4. Pragat (“manifest”): Purushottam cannot be perceived by mayic senses and minds. Yet, while remaining in Akshardham, he manifests in each brahmand with all his divine virtues, powers, etc., in human form and becomes visible to all. This is by his own divine resolve and out of loving compassion, to fulfill the wishes of his beloved devotees and for the ultimate liberation of infinite jivas and ishwars. That manifest form of Parabrahman Purushottam is Bhagwan Swaminarayan. Even after he retracts his earthly manifestation, he forever remains fully manifest through the Aksharbrahman Guru, making possible his worship in a manifest form and the path to ultimate liberation here and now.

The above summary is based on Pramukh Swami Maharaj’s creedal treatise, Svāminārāyaṇ Darśannā Siddhāntono Ālekh, and summarized from Swami Paramtattvadas’, An Introduction to Swaminarayan Hindu Theology (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha Today

Shastri Yagnapurushdas, better known as Shastriji Maharaj, was the third guru of the Guru Parampara and the founder of BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha. He is credited within the tradition for clarifying Akshar-Purushottam Darshan and initiating its propagation worldwide, popularizing it with the name Akshar-Purushottam.

In the early 1900s, against seemingly insurmountable challenges and with barely any means—he had no money, no other resources, hardly anything to even eat at times—and with only five swamis and a handful of devotees, Shastriji Maharaj began work on establishing mandirs dedicated to Akshar-Purushottam Darshan.

To formally propound Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, he established Bochasanwasi Shri Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha (BAPS) in 1907. Through incessant traveling, discoursing and letter-writing, he tirelessly explained the meaning of Akshar-Purushottam to devotees and seekers wherever he went.

By the time he passed away in 1951, Shastriji Maharaj had built five glorious mandirs, consecrating within them the murtis of Gunatitanand Swami (Akshar) and Bhagwan Swaminarayan (Purushottam) in the central shrines, thereby elucidating and immortalizing the doctrine of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan. He had also sown the seeds of BAPS outside of India, sending sanctified portrait images for a mandir in Nairobi, Kenya.

Shastriji Maharaj was succeeded by Yogiji Maharaj. Between 1951 and 1971, Yogiji Maharaj propagated Akshar-Purushottam Darshan around India, in East Africa, and also in Britain, where he inaugurated the first Swaminarayan Hindu mandir in the West, in Islington, north London, in 1970.

Pramukh Swami Maharaj, who had been appointed president of BAPS as a 28-year-old by Shastriji Maharaj, succeeded Yogiji Maharaj in 1971. He worked tirelessly until passing away in 2016, building more than 1,100 mandirs and expounding Akshar-Purushottam Darshan around the world.

The current guru of BAPS is Mahant Swami Maharaj. He travels the world, discoursing, writing letters and meeting people, inspiring them towards the beliefs, practices and values of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan. He also continues the tradition of building mandirs dedicated to Akshar-Purushottam Darshan. In 2017, he performed the ground-breaking ceremony for a traditional stone temple in Johannesburg, South Africa, and Sydney, Australia. In April of this year, he did the same for the BAPS Hindu Mandir in Abu Dhabi.

BAPS currently has 44 traditional spired mandirs and more than 1,200 other mandirs across a global network spanning North America, Britain, mainland Europe, Africa and the Middle East, the Asia-Pacific, and all of India. These mandirs welcome millions of worshipers, pilgrims, visitors and seekers every year. They are vibrant hubs of devotion, service, learning, festivity and community outreach—but above all, they are edifices of Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, dedicated to the worship of Parabrahman Purushottam Bhagwan Swaminarayan as exemplified by the Aksharbrahman Gurus.1 Each week, these mandirs are host to more than 3,850 satsang assemblies that teach this upasana (form of worship) and instill such Hindu values as personal integrity, family harmony and social responsibility. They are served by more than 1,000 BAPS swamis and 55,000 dedicated volunteers.

1. Bhagwan Swaminarayan explains in Vachanamrut Gadhada 2.27 that the very purpose of building mandirs is to uphold upasana.