South India’s Bhakti Saints

How a handful of God-adoring devotees changed the history of a nation

BY LAKSHMI CHANDRASHEKAR SUBRAMANIAN

SINGING THEIR HEART AND SOUL TO THE DIVINE, dedicating every verse as an offering, visiting the most auspicious of temples, recounting their personal encounters with the Lord, and living a life of faith, surrender and utmost devotion characterizes all the bhakti saints of India. Belonging to diverse communities, regions, historical periods and composing in different languages, styles and contexts, these poet-saints are bound together through time by their steadfast love of God.

The widespread devotional tradition of India is referred to as the Bhakti Movement. From around the 6th century onwards, as far as historians can tell, regional bhakti poetry has been flourishing in the Indian subcontinent in various local languages. The early Vaishnava and Saiva bhakti saints composed hymns at a time when Jainism and Buddhism were gaining major popularity. In the early seventh and eighth centuries, the Hindu Pallava and Chola kingdoms of southern India were at the height of their power. This, coupled with the burgeoning popularity of the divine songsters, kept Hinduism strong as it faced threats from other faiths. The bhakti environment created by these poet-saints influenced people from all walks of life, royalty and laymen, who were inspired by the pristine devotion of the saints and subsequently redefined their own lives as service to God.

Vast bhakti saint networks contributed not only to the religious landscape of the past, but also to today’s living tradition of devotion. Indian philosophy, music, dance, literature, history, visual art, architecture, film and popular media are all influenced by these poet-saints. Their compelling and lyrical songs permeate every major form of Indian classical dance and music. It is no surprise, then, that all Carnatic and Bharatanatyam dance compositions are devotional in nature. Every composition exudes intense and emotive bhakti rasa, which artists strive to express. Lakshmi Jayachandran of Singapore shares her love of the Tamil Saivite saints: “The most inspiring aspect of the Nalvars’ poetry is their intense love and devotion expressed in exquisite language that touches the heart so directly. An outstanding example of such melting devotion is the Thiruvachakam by Manikkavasagar.”

In the social sphere, the poet-saints’ inspiring lives form the basis for the stories that mothers and grandmothers tell their children, generation after generation. Their poignant verses still enter everyday contexts. Certain temples are regarded as uniquely sacred due to the saints’ presence in those spaces where they composed and sang their hymns.

In the 1980s Saroja Nagarathnam of Chennai created this remarkable art in which she depicts the four Samaya Acharyas of Saivism surrounded by the other Nayanars, with Madurai Meenakshi Temple in the background. Amazingly, this art is done entirely with bija mantras, hundreds of thousands of sacred words penned almost microscopically. No lines, no painting, just lettering. Many months were required to produce this image.

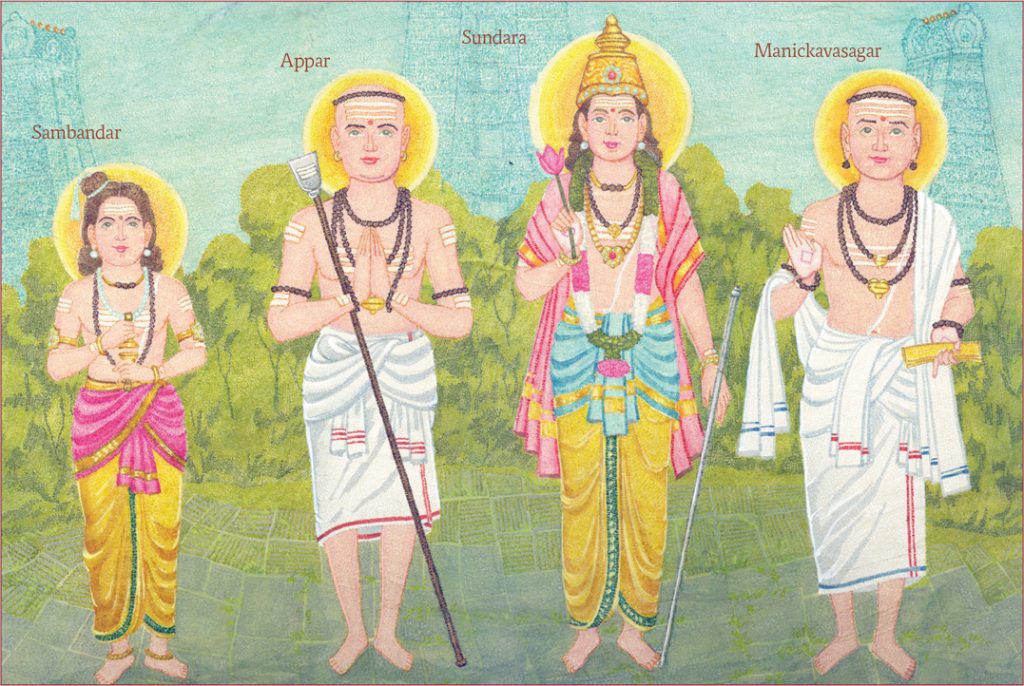

The 12 Alvars and 63 Nayanars of South India are hailed as the earliest groups of bhakti saints. Ardent devotees of Vishnu and Siva respectively, these 75 poet-saints composed soul-stirring verses in Tamil that set the groundwork for centuries of bhakti tradition. Of the Siva devotees, the Nalvar (Sambandar, Appar, Sundarar and Manikkavasagar), as well as female poet-saint Karaikkal Ammaiyar, had a great impact on Saiva Siddhanta philosophy as they sang about Siva as Personal Lord and Supreme Reality. Around 300 years later, in the 12th century, Basavanna and Mahadevi Akka carried the message of Virasaivism (heroic Saivism) in Karnataka through their vachanas in Kannada language. This poetry has a different flavor, a trenchant immediacy and radicalism, while expressing unflinching devotion to God Siva. Fast-forwarding to 16th century Vishnu-bhakti, Haridasa saint Kanakadasa composed Carnatic kirtanas in Kannada, while Poonthanam Namboodiri sang his praises in Malayalam to Lord Guruvayurappan, who is enshrined in Kerala.

Together, these poet-saints form an extended bhakti family that India has nurtured through the ages. The saints offer a universal path to liberation available to one and all. Every Indian region, from Kashmir to Kanyakumari, has played a major role in building this tradition of devotional religiosity. Bhakti transcends geographical boundaries and languages, uniting devotees in its universal message. It is an affirmation of India’s remarkable spirituality that saints, not soldiers, are history’s most lauded heroes.

In this Educational Insight, we focus on poet-saints with devotional poetry in the South Indian languages of Tamil, Kannada and Malayalam. In the future we will devote an entire feature to Telugu, another beautiful South Indian language, which is the vehicle of expression for most Carnatic composer-saints. In this Insight we feature 21 South Indian bhaktas who lived over a span of 1,000 years, between the 6th and the 16th centuries.

The Alvars: Tamil Nadu, ca 500–900

As torchbearers of the Sri Vaishnava tradition of South India from the sixth through ninth centuries, the 12 Alvars of Tamil Nadu spread the message of fervent love, devotion and spiritual surrender unto the Divine. Alvar means one who is “immersed deeply in” the love of God. These poet-saints, all great devotees of Maha Vishnu, came from diverse communities in the Tamil South. They traveled to temples far and wide, collectively composing 4,000 hymns (pasurams) in praise of Vishnu and Krishna. In the 10th century, theologian Nathamuni compiled their works as the Nalayira Divya Prabandham (Divine Collection of 4,000 Hymns) and set them to music for singing in temples. The Divya Prabandham is hailed as the “Vedas of the Dravidians,” as they convey the message of the Vedas and Upanishads in accessible Tamil. The Alvars propound a personal and emotional approach as they dote on and chide Perumal/Vishnu through their passionate bhakti poetry, which devotees memorize, recite, sing, listen and dance to. The songs of the Prabandham are regularly sung in South Indian Vishnu temples and homes, especially during festivals.

Avatars

Traditional accounts portray each Alvar as an incarnation of a divine aspect of the Supreme Maha Vishnu, as follows:

Poigai Alvar: Panchajanya (Vishnu’s conch)

Bhoothath Alvar: Kaumodaki (Vishnu’s mace)

Pey Alvar: Nandaka (Vishnu’s sword)

Thirumazhisai Alvar: Sudarshana Chakra (Vishnu’s discus)

Nammalvar: Vishvaksena (Vishnu’s army commander)

Madhurakavi Alvar: Vainatheya (Vishnu’s eagle Garuda)

Kulasekhara Alvar: Kaustubha (Vishnu’s divine gem)

Periyalvar: Garuda (Vishnu’s vahana/vehicle)

Sri Andal: Bhudevi (Vishnu’s wife, Lakshmi)

Thondaradippodi Alvar: Vanamalai (Vishnu’s garland)

Thiruppan Alvar: Srivatsa (auspicious mark on Vishnu’s chest)

Thirumangai Alvar: Saranga (Vishnu’s bow)

Poigai Alvar, Bhoothath Alvar, and Pey Alvar, three contemporaries, are considered the Mudal Alvars (first Alvars). Here we feature two other Alvars who were highly renowned.

Andal

Born in Srivilliputhur and brought up by Periyar (also an alvar), the maiden named Kothai maintained that she would marry only Lord Ranganatha of Thiruvarangam. Her devotion and surrender earned her the name Andal, the girl who “ruled” over the Lord. Her ardent wish was to merge with her divine beloved Perumal, which happened when she was only 15 years old. Andal, the only female poet-saint among the Alvars, composed the great Thiruppavai and Nachiar Thirumozhi as offerings to her darling Kannan (an endearing name of Ranganatha). These hymns are recited whenever bhaktas celebrate her inspiring devotional legacy, especially during the annual Markali festival.

Nammalvar

Nammalvar (“our Alvar”) is one of the most famous and prolific of the group. His poetry contributed greatly to philosophy and theology of Tamil Vaishnavism. Along with the hymns of the Saiva Nayanars—Appar, Sundarar and Sambandar—Nammalvar’s soul-stirring Tamil poetry had a deep impact on the South Indian Pallava kings. At a time when Buddhism and Jainism played a major role in society and threatened to displace Hinduism, these saints inspired royalty and common people alike to hold firmly to the Hindu path and tradition.

Divya Desam

To the Alvars, the Lord is not a mere idea but a concrete presence. Through their magnificent hymns in the Divya Prabandham, the saints sang about Lord Vishnu presiding in 108 temples. Each of these temples is celebrated as a Divya Desam, “divine precinct,” and together form a map of sacred geography and pilgrimage for the Sri Vaishnava community. India is home to 105 of these sanctuaries, spread across Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand. One Divya Desam is in Nepal, and two are in celestial realms—Thiruparkadal (ocean of milk upon which Vishnu reclines), and Paramapadam (Vishnu’s heavenly abode, Vaikuntha).

Inspired by Andal

“Andal offers a garland after trying it on herself, showing us that the Lord accepts what is offered with pure, unadulterated love. On a deeper level, there is an Andal in every young girl who dreams of a life partner worthy of worship, love and respect. A dancer can easily tap into that sentiment when we depict Tiruppavai and Varanam Ayiram.”

SHOBHA SUBRAMANIAN, BHARATANATYAM DANCER & JAYAMANGALA DANCE DIRECTOR, MARYLAND, USA

Did You Know?

The beautiful Srirangam Temple, glorified in the Divya Prabandham, is the largest functioning Hindu temple in the world, drawing a million devotees during the annual 21-day Markali festival in December–January. Tiruvenkata Divya Desam, one of the two kshetrams in Andhra Pradesh, is a cluster of three temples, one of which is the hugely celebrated Tirumala Venkateswara Temple at Tirupati. The term Sri Vaishnava can be found in 10th-century inscriptions in this temple.

LEARN MORE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Image Visit the 105 Divya Desams in India, and one in Nepal

Image Listen to the Divya Prabandham on YouTube or in Vishnu temples

Image Read Vasudha Narayanan’s Weaving Garlands in Tamil: The Poetry of the Alvars

Alvar Pasurams

TRANSLATED BY VASUDHA NARAYANAN

By Poigai Alvar

With the earth as the lamp, the sweeping oceans as the ghee,

and the sun with its fiery rays as the flame,

I have woven a garland of words for the feet of the Lord

who bears the red flaming wheel, so I can cross the ocean of grief.

By Nammalvar

O wondrous one who was born!

O wondrous one who fought the Bharata war!

Great one who became all things,

starting with primal elements:

wind, fire, water, sky and earth.

Great one, wondrous one, you are in all things,

as butter lies hidden in fresh milk; you stand in all things

and yet transcend them. Where can I see you?

By Andal

A prankster who knows no dharma,

He whose eyebrows arch

like the bow Saranga in his hand,

handsome one without equal,

have you seen him? He whose form is dark,

whose face glows bright like the sun that fans

on the peaks of the rising hills,

we have seen him here, in Vrindavanam.

By Periyalvar

Like the king of the serpents opening his many hoods

and supporting the vast worlds on it,

The five fingers of Damodara’s hand opened

like the petals of a flower and held aloft Govardhana.

This is the hill where the monkeys carry their babies

and sing in praise of Hanuman,

who caused such havoc in Lanka,

and lull their little ones to sleep.

The Nalvars: Tamil Nadu, ca 600–90

During the 6th through 9th centuries, South India was home to 63 fervent devotees of Lord Siva who became known as the Nayanars (or Nayanars). Several among these pious souls, coming from all segments of society—potter, fisherman, farmer, merchant, priest, hunter, washerman—composed devotional hymns that are sung to this day by devotees worldwide. A festival dedicated to the 63 Nayanmars, the Arupathu Moovar Thiruvila, is held annually at Kapaleeswarar Temple in Chennai, Tamil Nadu.

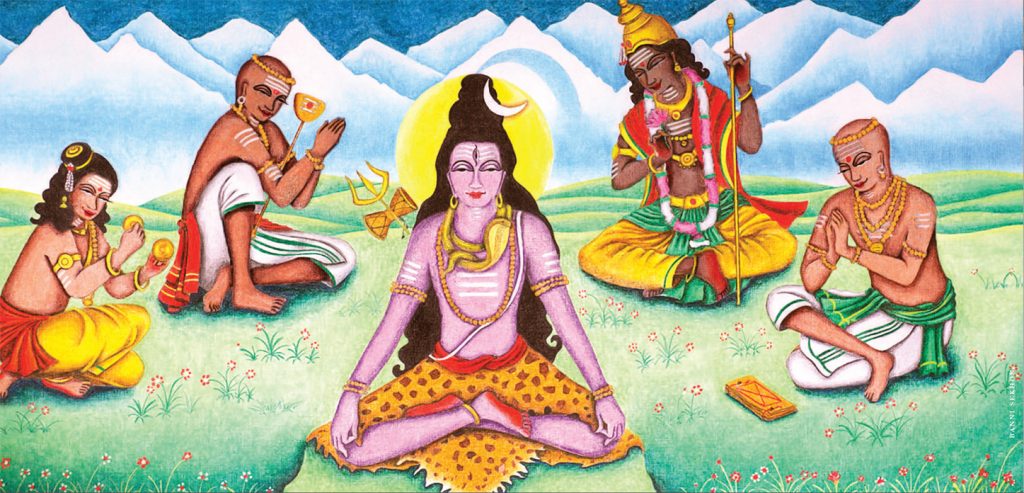

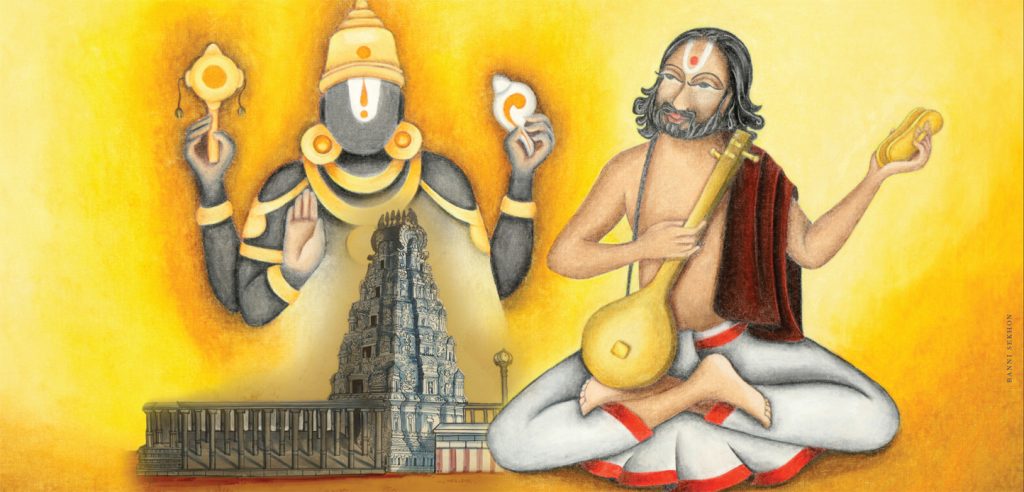

Three of the most prominent Nayanars—Appar, Sambandar and Sundarar (composers of Thevaram hymns)—along with Manikkavasagar are called the Samayacharyas (teachers of the faith) referred to in Tamil as Nalvar, “The Four.” They promoted Saiva Siddhanta philosophy and culture, countering the incursion of Jainism and Buddhism. They taught that Siva is Love and that love (for all beings—indeed, for all existence) is the key to reaching Siva, the Supreme Being.

Sambandar

Thirugnana Sambandar was born to a pious Brahmin couple in Sirkali in the 7th century after the father had prayed to Lord Siva for a worthy son who would reestablish the glory of Saivism. When he was three, his parents took him to Sattainathar Siva Temple and told him to wait near the pond. Soon the child started crying, and Goddess Parvati, along with Lord Siva as Thoniappar, came to console and nurse him. When the parents returned, they saw milk on his mouth and asked who had fed him. Sambandar pointed heavenward, spontaneously singing his first hymn about Siva, “Thodudaiya Seviyan.” The milk is regarded as Sivajnanam, milk of divine wisdom or knowledge of Siva, and the child became known as Thirugnana Sambandar (the saint related to God by knowledge), and as Aludaiya Pillayar (the Lord’s child).

Sambandar is glorified in the Periyapuranam as Tala Vendan, the unparalleled king of rhythm. The prodigy starting singing about the Vedas at age seven, eventually composing a body of hymns that comprise volumes 1-3 of the Thirumurai, the 12-volume compendium of hymns and writings by South Indian Saivite saints. In his short life Sambandar bested Jain monks in debate and brought the hunchbacked king Koon Pandyan (later Sundara Pandyan) back into the Saivite tradition.

When a wedding was arranged for him at age 16, Sambandar sang to Siva seeking liberation. Legend tells us that there appeared a great blaze of light—Siva Jyoti, the light of Siva. Then, as Sambandar composed the “Panchakshara Padigam,” everyone present attained union with Lord Siva, the source and final destination of all.

Thirunavukkarasar, or Appar

The 7th-century poet-saint Thirunavukkarasar pilgrimaged on foot to at least 125 Tamil Nadu temples, humbly sweeping the temple paths, worshiping and composing hymns praising Siva. When he met child-saint Sambandar, he prostrated at the boy’s feet. Sambandar reciprocated and respectfully addressed him as Appar (father), the name by which he is commonly known.

Born as Maruneekkiyar in a Vellalar family of Saivites in Tiruvamur village, the saint lost his parents as a child and was mothered by his sister Tilakavathiyar. The transience of life stimulated in him a yearning for everlasting truth. He joined a Jain monastery, and his sister prayed to Siva to bring him back to Saivism. The boy fell severely ill and returned home. Brother and sister prayed at Thiruvadigai Temple, and Maruneekkiyar was cured. Becoming a fervent Siva devotee, he composed many Siva hymns (Thirumurai volumes 4-6) and was named Thirunavukkarasar, “king of divine speech.” At 81, Appar attained mukti at Agnipureeswarar Siva Temple in Thirupugalur.

Sundarar

Sundaramurti Nayanar, uniquely, was born to parents who are also Nayanars, around 800ce. His hymns comprise the seventh Thirumurai volume. When he was about to get married, an old ascetic covered in sacred ash and rudraksha beads interrupted the wedding, claiming that Sundarar was his slave, citing a palm-leaf manuscript. Sundarar called him a pitthan (lunatic). But the palm leaf proved valid, and Sundarar followed the man to the Thiruvennainallur Siva temple, where the ascetic disappeared into the sanctum. Lord Siva asked Sundarar to compose a hymn with the word pitthan per his initial address. Sundarar sang this first hymn, “Pittha pirai choodi” (O crazy one wearing the crescent moon), venerating the Lord at Tiru Arul Turai Temple (today’s Kripapureeswarar Perumal Temple), one of 82 Siva temples he visited in his life. Sundarar lived only 18 years but became one of the foremost saints of Tamil Saiva poetry.

Manikkavasagar

Manikkavasagar was born as Vadavurar in a Saivite priest family in 9th-century Thiruvadavur, near Madurai, and rose to become prime minister to the Pandyan king. According to later accounts, one day the king gave him a large sum of money to purchase war horses. On the way, the minister was drawn to an ascetic (who was in fact Lord Siva) sitting with disciples under a tree. Vadavurar, taking the sage as his guru, sat at his feet in meditation and received enlightenment. Totally forgetting the king’s assignment, he renounced the world and used the royal funds to build the Athmanathaswami Temple (Avudaiyarkoil).

The hymns of Manikkavasagar (“he of ruby-like utterances”), comprising Thirumurai volume 8, express his aspirations, trials and yogic realizations, praise the Namasivaya mantra, and stress cultivating love for Siva. The king, too, was blessed by Lord Siva and gave up his throne to pursue spiritual life. Sculptures illustrating the poet-saint’s life can be found in the Madurai Meenakshi Sundaresvara Temple and in the Chidambaram Nataraja Temple, where he spent his final days.

LEARN MORE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Read Sixty-Three Nayanar Saints by Swami Sivananda

Listen to Tevaram

Visit the Padal Petra Sthalams in South India, 275 temples revered in Tevaram

Nalvar’s Padigams

By Appar

Wherever His devotees are born, into whatever form or birth,

to bless them with His grace in that very form

is the nature of Shankara, my bull-riding Lord

with body bright as the white conch,

who lives in Piramapuram, cool with

groves of fragrant flowers.

He is drum and drumbeat, the measure of all speech.

The ash-smeared God, the supreme Light,

destroyer of our sin, is our one path to release.

The Lord who kicked at terrible Death

firmly eludes evil men—they can’t see Him.

My Father in Karukavur is my eye.

By Sundarar

You have many temples. Honoring them, singing their praise,

I have been cured of confusion and karma,

O master of the path that the Gods do not know!

O Lord, you sat under the spreading banyan tree

and taught the sacred law at the beautiful temple,

the auspicious temple, the Alakkoyil temple

in the northern part of cool Punkachur town!

TRANSLATED BY INDIRA VISWANATHAN PETERSON

By Manikkavasagar

Spheres of heavens pervading the cosmos,

Limitless, uberous and in multitudinous forms,

Excelling each other in beauty and comeliness,

Exceeding in number a thousand million…

The Primordial One transcending words and meaning,

The One whom the thoughts fail to reach,

The One whom the net of devotion can catch,

The One, indeed the only One,

Expands He as the expanding magnificence of all existence.

Indwells He as the infinitely small essence of the atom.

BY JATAAYU, SWARAJYAMAG.COM

BASED ON THE TRANSLATION BY DR. TN RAMACHANDRAN

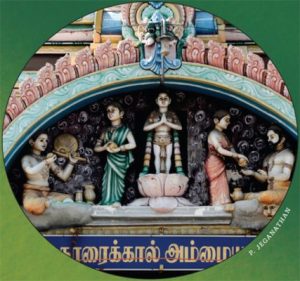

Karaikkal Ammaiyar: Tamil Nadu, ca 500

Hailing from the coastal town of Karaikkal in present-day Tamil Nadu, Karaikkal Ammaiyar (the “revered mother of Karaikkal”) is one of the most renowned female devotees of Lord Siva. She lived around the 6th century and was a significant contributor to early Tamil bhakti literature during the “Saiva Age” (ca 5th–13th century), when the worship of Lord Siva was predominant across India. Karaikkal Ammaiyar is known as the first Siva-bhakti poet-saint in Tamil language literature, and one of only three female Nayanars, along with Isaijnaniyar and Mangayarkarasiyar. Karaikkal Ammaiyar was born as Punitavati, “the pure one,” in a prosperous merchant family in the Nattukottai Chettiar community. The little girl was profoundly devoted to Lord Siva. As soon as she came of age, beautiful Punitavati was married to Paramadattan, a wealthy merchant.

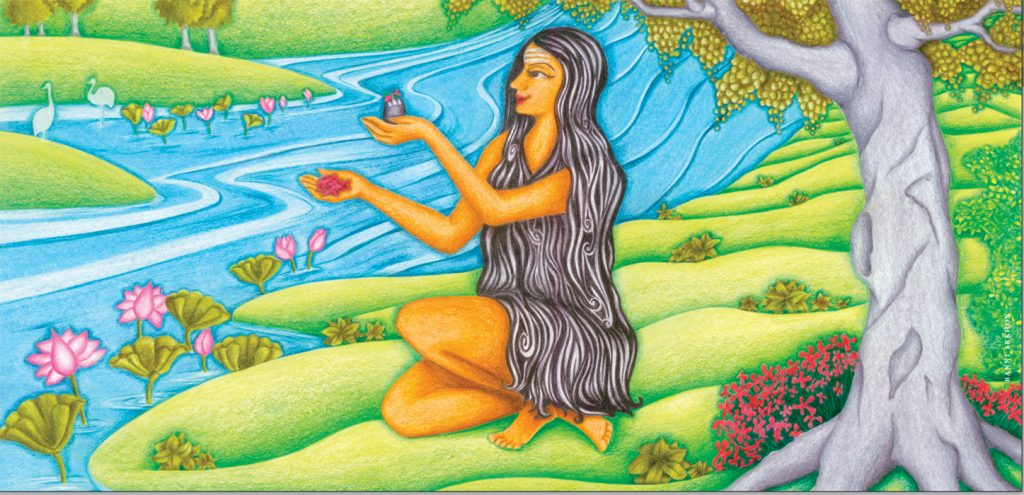

Punitavati Becomes Karaikkal Ammaiyar

Punitavati and Paramadattan were a happily married couple. One day Paramadattan sent home two mangoes from work, which his wife saved for him. That same day, a holy man visited her house seeking alms. With nothing else to offer, she gave him one mango with cooked rice. The Siva devotee ate the food, blessed her and left. When Paramadattan returned home, Punitavati served him the remaining mango. Enjoying the fruit, he asked for the second. Punitavati was in a fix; she did not want to tell her husband she had given the mango away. Eyes closed, palms open in prayer, she prayed to Lord Siva. Miraculously, a mango appeared in her hands! She thanked the Lord and joyfully took the mango to her husband. Tasting the fruit, however, he noticed a difference. When he probed further, Punitavati told him that mango was from Lord Siva. Paramadattan was incredulous and challenged her to get one more mango from the Lord. Due to her unshakable faith and prayers, Siva materialized another mango in her hands, but when Paramadattan reached for it, the fruit disappeared. This moment changed Punitavati’s life, laying the bricks for her transformation into the poet-saint Karaikkal Ammaiyar. Paramadattan left his wife and the town, and eventually remarried. Many years later, he returned with his new wife and daughter (whom they had named Punitavati) to seek the blessings of Karaikkal Ammaiyar, whom he now considered a goddess.

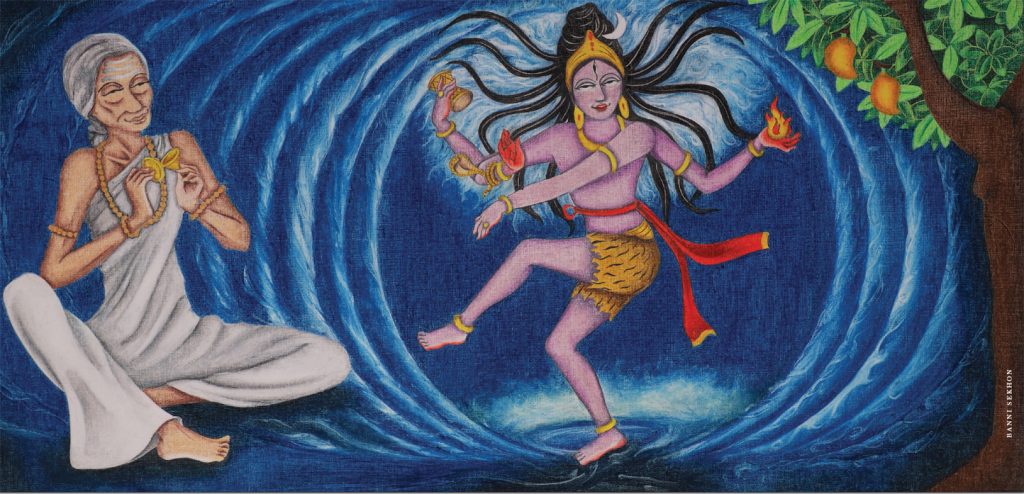

Realizing that her young, beautiful form would only be a source of unwanted complications in her life, she prayed to Siva to grant her the appearance of a pey, meaning ghoul in Tamil. Lord Siva granted her wish by freeing her from all worldly hindrances, and the transformed Ammaiyar spontaneously sang the “Arputat Tiruvantati,” her longest devotional work. From then on, Karaikkal Ammaiyar became known as Peyar, as she assumed the form of an emaciated old woman.

The transformed bhaktar went on pilgrimage to Mount Kailash, Siva and Parvati’s sacred abode in the Himalayas. Considering it a sin to place her feet on the blessed mountain, she made the journey on her hands. As described in Karen Pechilis’ work, Karaikkal Ammaiyar beseeched the Lord: “May those who desire you with undying joyful love not be reborn; if I am born again, may I never forget you; may I sit at your feet, happily singing while you, virtue itself, dance.” Lord Siva told her to visit Thiruvalangadu, where she would witness His cosmic dance.

Mystic Poetry

Karaikkal Ammaiyar devoted her life to singing hymns in praise of Siva, though her biographical story might be even more popularly known than her poetic contributions. We know of four devotional works that Ammaiyar composed, a total of 143 verses, through which she invented certain Tamil poetic forms, including the antati genre, in which the last word of every verse is the same as the first word of the following verse of the poem.

Themes in Ammaiyar’s poetry include Siva as the heroic ideal, His majestic cosmic dance as Nataraja, Ammaiyar’s servitude, ridiculing those who don’t see Siva as the ultimate goal, and the spiritual significance of the cremation ground. Ammaiyar urges us to constantly meditate on Lord Siva rather than focusing on rituals. She signed some of her poems as “Karaikkal-pey,” as per the form that she requested Siva to bless her with. Her eloquent poetry, at times filled with imagery of death and decay, demonstrates the path of devotional love that leads a human being to liberation from the cycle of birth and death.

During the Chola rule in the 12th century, around 600 years after Ammaiyar’s time, her biography was included in the Periyapuranam (“great narrative”) of court poet Sekkilar, with 4,253 verses in Tamil describing the lives of the 63 Nayanmars. This work, also known as the Thiruthondar Puranam, is one of the popular texts of the Saiva cannon. In art, Ammaiyar is often depicted as an old woman, cymbals in hand and with a joyful smile expressive of her oneness with Siva. Sculptures of this extraordinary poet-saint, some created during the Chola period, can be viewed in museums around the world.

The temple most closely associated with the life of Karaikkal Ammaiyar is the Sri Vadaranyeswarar Temple in Thiruvalangadu, one of the five renowned Nataraja temples, where Lord Siva performs the Cosmic Dance (Siva tandava). Here Karaikkal Ammaiyar settled down with Siva’s guidance, composed hymns, watched Lord Siva dance into eternity and ultimately attained spiritual liberation (mukti). Her saint-day is celebrated here each year.

In 1929, the Karaikal Ammaiyar Temple was constructed by Malaiperumal Pillai in the center of Karaikkal, the birthplace of the poet-saint. The main Goddess here is Punitavati—Karaikkal Ammaiyar herself. The annual mango festival, called the Mangani Tirunal festival, is celebrated to commemorate the great mango legend associated with the saint.

LEARN MORE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Sri Vadaranyeswarar Temple & Karaikal Ammaiyar Temple in Tamil Nadu, India

Interpreting Devotion, by Karen Pechilis

“Karaikkal Ammaiyar” Tamil film (1973)

Karaikkal Ammaiyar’s Poetry

TRANSLATED BY ELAINE CRADDOCK

Look!

Having become a slave to the beautiful feet of the

One whose red matted hair has the waves of Ganga,

We have realized Him through scriptures,

We have become suitable for this life and for the other world.

Why do others gossip about us behind our backs?

Understand us. (Arputatiruvantati, 91)

I thought of only One.

I was focused on only One.

I kept only One inside my heart.

Look at this One!

It is He who has Ganga on His head,

A moonbeam in His hair,

A radiant flame in His beautiful hand.

I have become His slave. (Arputatiruvantati, 11)

My heart!

Give up your bondage, your wife and children.

Saying that you take refuge here at His feet,

Think of Him and worship. (Tiruvirattai Manimalai, 13)

Not following a false path ruled by the five senses,

We have achieved merits,

Because of the Lord’s love for His slaves. (Tiruvirattai Manimalai, 16)

He is the one who knows.

He is the one who makes us know.

He is the one who knows, because He is knowledge itself.

He is the truth that is to be known.

He is the sun and moon, the earth, sky,

And all the other elements. (Arputatiruvantati, 20)

Akka Mahadevi: Karnataka, c.1130-1160

Afervent devotee of Lord Siva, Akka Mahadevi was a poet-saint in the Virasaiva tradition, a Saivite Hindu religious movement that became popular in 12th-century South India. The prefix Akka is an honorific meaning “elder sister,” which Mahadevi earned as the archetypal sister in the Kannada-language bhakti tradition.

Kannada is a Dravidian language largely spoken in Karnataka, and globally in the Indian diaspora. It has a long and rich literary tradition, to which Akka Mahadevi contributed immensely, composing hundreds of poems (300 still known) as offerings to God. Each poem in this genre is known as a vachana, meaning “saying” or “utterance.” The form is free-verse lyrics, usually produced as couplets in six to twelve lines. Vachanas carry a rhythmic structure not through sound, as is the case in most poetry, but through semantics and sentence patterns. Vachanas are so profound and experientially rich that they are revered as Kannada-language Upanishads. Two short compositions by Mahadevi, Mantragopya and Yogangatrividhi, are considered her finest contributions. Her spiritual brothers in the famed assembly of Kannada poets were Dasimayya, Basavanna and Allama Prabhu.

Akka Mahadevi’s vachanas are “highly personal, highly poetical, imaginative expressions of mystical experiences and spiritual insights, in which mystical bridal imagery abounds,” says Dutch-Canadian scholar Robert Zydenbos. As present-day seekers, we meet Mahadevi Akka through her vachanas, in which she demonstrates the various sthalas, or stages of spiritual development, and exemplifies three forms of love commonly found in Sanskrit poetry: love forbidden, love in separation, and love in union. A strong bhakta and leader of the Virasaiva movement in her time, Akka Mahadevi is a feminist icon for social activism even today.

Mahadevi’s Legendary Life

Mahadevi was born in Udutadi village, around 1130, in the Shimoga district of Karnataka. Initiated into Saivite tradition at age ten, she thereafter considered herself to be truly born. As she grew into a beautiful maiden, some thought of her as Rudrakannike, a Goddess born on Earth with a spiritual purpose. Even as a child, Mahadevi was captivated by Lord Siva as Chennamallikarjuna, “beautiful Lord, as white as jasmine,” the main Deity in her village temple. The name Chennamallikarjuna appears in all of her poems, both as a signature (ankita) and an invocation of Siva.

Like Andal in South India and Mirabai in the North, Mahadevi considered none other than the Lord Himself as her life partner. One day a king named Kaushika saw Mahadevi and fell in love with her. When he approached her parents to request her hand in marriage, Mahadevi protested. Not only was he no comparison to Chennamallikarjuna, but he didn’t even believe in the existence of God. By the prevailing account, as fate would have it, Kaushika persuaded Mahadevi’s parents and took the maiden as his bride. Chandra Mudaliar writes that one of her poems includes three conditions for her marriage, including that she be free to spend her time in devotion, or in conversation with other saints (Religious Experiences of Hindu Women: A Study of Akka Mahadevi). By other accounts, she never married Kaushika, or they did marry but never actually lived together.

Kaushika was a materialistic man who gave prime importance to sense pleasures, while Mahadevi had transcended worldly existence and was fully absorbed in her devotion to the Lovely Lord White as Jasmine. Not surprisingly, Akka Mahadevi’s vachanas address these conflicts and portray her yearning for her beloved and only legitimate husband, Chennamallikarjuna.

Over time, Kaushika exerted his will on her so strongly that she decided to preserve her dignity by leaving him for good. Legend tells us that she abandoned her birthplace, parents, and even clothing, as the ultimate act of social defiance. She became a wandering renunciate, covered only in her tresses, searching for Chennamallikarjuna and the company of His devotees.

She ultimately reached Kalyana in northern Karnataka, the epicenter of Virasaiva bhakti, where she met poet-saints Allama Prabhu and Basavanna. That is when the famous conversation between Allama and Mahadevi took place, a guru-disciple dialogue of sorts, during which Allama asked her about the identity of her husband, to which she replied that she was married forever to Chennamallikarjuna. He then asked her the obvious question (from Speaking of Siva, A.K. Ramanujan): “Why take off clothes, as if by that gesture you could peel off illusions? And yet robe yourself in tresses of hair? If so free and pure in heart, why replace a sari with a covering of tresses?’ Her reply is boldly honest: “Till the fruit is ripe inside, the skin will not fall off. I’d a feeling it would hurt you if I displayed the body’s seals of love. O brother, don’t tease me needlessly. I’m given entire into the hands of my lord white as jasmine.” Her answer was so profound that she was thereafter accepted into the company of the Virasaiva saints.

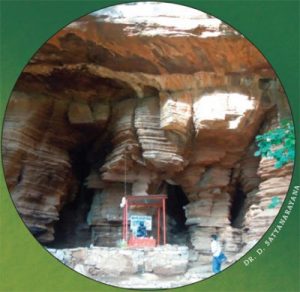

Akka Mahadevi spent time in the town of Kalyana at the Anubhava Mantapa, a famed Virasaiva forum for spiritual discussion, then continued her wild, God-intoxicated pilgrimage. She eventually reached the holy Srisailam mountains, in present-day Andhra Pradesh, where she found Lord Mallikarjuna and became lost in Him. She was hardly in her twenties when she walked into the Kadali forests and gave up her body into oneness with Siva.

A vachana attributed to Akka Mahadevi suggests that towards the end of her life, King Kaushika visited her in the forest and sought her forgiveness.

Enjoy Speaking of Siva, by A.K. Ramanujan

Read Mahadeviyakka, Oxford Bibliographies by Robert Zydenbos

Read “Akka Mahadevi in Hinduism and Tribal Religions,” Encyclopedia of Indian Religions by Sushumna Kannan

Visit the Akka Mahadevi Caves in Srisailam, Andhra Pradesh, India

Akka Mahadevi’s Vachanas

TRANSLATED BY A.K. RAMANUJAN, SPEAKING OF SIVA

Like…

treasure hidden in the ground

taste in the fruit

gold in the rock

oil in the seed,

the Absolute, hidden away

in the heart

no one can know

the ways of our lord

white as jasmine.

You are the forest

you are all the great trees

in the forest

you are bird and beast

playing in and out

of all the trees

O lord white as jasmine

filling and filled by all,

why don’t you

show me your face?

Four parts of the day

I grieve for you.

Four parts of the night

I’m mad for you.

I lie lost,

sick for you, night and day,

O lord white as jasmine.

For hunger,

there is the town’s rice in the begging bowl.

For thirst,

there are tanks, streams, wells.

For sleep,

there are the ruins of temples.

For soul’s company,

I have you, O lord

white as jasmine.

I love the Handsome One:

He has no death

decay nor form

no place or side

no end nor birthmarks.

I love him O mother. Listen.

I love the Beautiful One

with no bond nor fear,

no clan, no land, no landmarks

for his beauty.

So my lord, white as jasmine,

is my husband.

Take these husbands who die,

decay, and feed them

to your kitchen fires!

Basavanna: Karnataka, 1106–116

Basava means “bull” in Kannada. The name well suits this reformer, political activist, philosopher and poet-saint who embodied the spirit of Siva’s divine bull, Nandi, as he boldly spread social awareness through his powerful vachana verses. A 12th-century saint from Manigavalli, Basavanna (the suffix anna means “elder brother”) lived in Karnataka during the reign of the Kalachuri king Bijjala I. Learned in the traditional Sanskrit classics, an ardent Saivite, he devoted his life to serving the Lord.

Basavanna lost his parents in childhood and grew up under the care of a grandmother and foster-parents, Madiraja and Madambike, a brahmin couple of Bagevadi village. Early in life, he rebelled against the strictures of caste, orthodoxy and ritual, renouncing it all by the age of 16 when he decided to spend his life worshiping and serving Siva. His 15th-century poet-biographer, Harihara, wrote, “‘Love of Siva cannot live with ritual.’ So saying, he tore off his sacred thread which bound him like a past-life’s deeds…and left the shade of his home, disregarded wealth and propriety, thought nothing of relatives. Asking no one in town, he left Bagevadi, raging for the Lord’s love, eastwards… and entered Kappadisangama, where three rivers meet’’ (from Speaking of Siva, by A.K. Ramanujan). There, Basavanna sang to and about his chosen form of God, Siva as Kudalasangamadeva, Lord of the Meeting Rivers. This name appears as a signature in all of Basavanna’s poetry.

In Kudalasangama, Basavanna met his guru, Ishanya Guru, a Saivite brahmin of the Kalamukha sect, and spent several years studying with him. One night, as legend has it, Basavanna had a dream-vision in which Lord Siva directed him to leave Kudalasangama and go to Mangajavada, where King Bijjala I reigned. In the dream Basavanna protested. Soon thereafter a small Sivalinga manifested for him in the mouth of the temple Nandi. Reassured of Siva’s intent by this miraculous omen, Basavanna set out for Mangajavada. He visited Kalyana, where he married his cousin Gangambike and her close friend Nilambike. Gangambike was the daughter of his uncle Baladeva, a minister of King Bijjala I. Basavanna soon became the king’s trusted friend; and when Baladeva died, the king made Basavanna his new finance minister.

In Mangajavada, Basavanna eagerly began implementing the social ideals instilled in him by Ishanya Guru, spreading the message of a new, visionary religious society. He utilized state funds to undertake social reforms, and also to serve and empower wandering Virasaiva ascetics, or jangamas. At age 48 he moved with King Bijjala to Kalyana, where, joined by Allama Prabhu, his fame continued to grow for the next fourteen years.

In Kalyana, Basavana set up innovative public institutions such as the Anubhava Mantapa, where male and female devotees from all socio-economic backgrounds were welcomed to discuss spirituality, as well as economic and social issues. Many Virasaiva saints gathered in this famed “Hall of Experience,” including Allama Prabhu and Mahadevi Akka. All of this led to a renaissance of Siva worship, and gave rise to a new form of Virasaivism called Lingayatism. Here Basavanna lived and preached for twenty years, developing a large Saivite movement. “A new community with egalitarian ideals disregarding caste, class and sex grew in Kalyana, challenging orthodoxy, rejecting social convention and religious ritual. A political crisis was at hand” (Speaking of Siva).

Eventually, the king, persuaded by gossip about his minister, moved to curb the rise of the movement. Traditionalists in the caste-oriented larger society were outraged when, in 1167, a wedding took place between two devotees of different castes (brahmin and shudra), though both had renounced caste in joining the casteless Virasaiva community. King Bijjala sentenced the fathers of the bride and bridegroom to death. “Meanwhile, extremist youths were out for revenge; they stabbed Bijjala and assassinated him. In the riots and persecution that followed, Virasaivas were scattered in all directions. But in the brief period, probably the span of one generation, Basavanna had helped create a new community.” (Speaking of Siva). Basavanna, who was committed to nonviolence but unable to restrain the extremists, left Kalyana and returned to Kudalasangama, where he became one with the Divine soon thereafter at the age of 62.

Basavanna wanted to inspire all people—both the lettered and unlettered, regardless of caste, class or gender—with his teachings on the path to Siva. His teachings were embodied in simple vachana verses, written in praise of Lord Siva in the common Kannada language. In his verses he repudiated social discrimination, superstitions, rituals and traditions, such as wearing the sacred thread. Rejecting temple rites led by brahmins, he advocated personal, direct worship of Siva, introducing the Ishtalinga necklace encasing a Sivalinga to serve as a reminder of one’s devotion to Siva and the Lord’s constant presence. Lingayat devotees faithfully perform puja to their personal Lingam every day while holding it in the palm of the left hand. Basavanna suggested treating one’s own body and soul as a temple of Siva. His verses, such as “Kayakave Kailasa” (referring to “work is worship”), remain enormously popular. As a key figure, Basavanna contributed greatly to Virasaiva devotional history, religion and contemporary politics. Several statues of the saint have been erected; the most prominent, at Basavakalyana (formerly Kalyana; renamed after the saint), is 108 feet tall.

Did you know?

Virasaivites, “ardent Siva worshipers,” consider Kudalasangama a key pilgrimage site. Poet-saint Basavanna’s Aikya Mantapa (holy samadhi) as well as the Swayambhu (self-manifested) Lingam can be found here.

LEARN MORE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Read Speaking of Siva by A.K. Ramanujan

Visit Kudalasangama, Karnataka, India

Basavanna’s Vachanas

TRANSLATION BY A.K. RAMANUJAN, SPEAKING OF SIVA

When, like a hailstone crystal,

like a waxwork image,

the flesh melts in pleasure,

how can I tell you?

The waters of joy

broke the banks

and ran out of my eyes.

I touched and joined

my Lord of the Meeting Rivers.

How can I talk to anyone

of that?

The eating bowl is not one bronze

and the looking glass another.

Bowl and mirror are one metal.

Giving back light, one becomes a mirror.

Aware, one is the Lord’s;

unaware, mere human.

Worship the Lord without forgetting, the Lord of the Meeting Rivers.

Milk is left over

from the calves.

Water is left over

from the fishes,

flowers from the bees.

How can I worship you,

O Siva, with such offal?

But it’s not for me

to despise left-overs,

so take what comes,

Lord of the Meeting Rivers.

The pot is a god.

The winnowing fan is a god.

The stone in the street is a god. The comb is a god.

The bowstring is also a god.

The bushel is a god

and the spouted cup is a god.

Gods, gods, there are so many, there’s no place left for a foot.

There is only one God. He is our Lord of the Meeting Rivers.

Kanakadasa: Karnataka, 1509–1609

One of India’s famous bhaktas was the 16-century poet-saint Kanakadasa. He is known as a Haridasa, part of a devotional movement that originated in Karnataka and spread the teachings of Madhvacharya in that state and eastward into Bengal and Assam over a span of nearly six centuries. History counts ten or more Haridasa saints and mystics who helped shape the culture, philosophy and art of South India. Kanakadasa composed numerous works in easily understandable Kannada that are treasured in the Carnatic music tradition. He is best known for his characteristically bold kirtanas.

Named Thimmappa Nayaka at birth, he was the son of Biregowda and Beechamma of Bada village in Karnataka’s Haveri district. Exemplary and well educated, Thimma became the village chieftain. Based on one of his compositions, it is interpreted that after he was severely injured in a war and miraculously saved, he renounced his warrior profession and devoted his life to composing music and literature to explain philosophy in the language of ordinary people. He became a devotee of Lord Krishna, worshiping the Lord as Adikeshava at a small shrine near his home. Surrendering his princely life, he moved to nearby Kaginele village. In time, he became a follower of the great Dvaita philosopher Vyasatirtha from the Madhva order of Udupi.

Vyasatirtha was the patron saint of the Vijayanagara empire and guru of the ruler, Krishna Deva Raya. He is famous for composing the popular Carnatic song “Krishna Ni Begane Baaro” in Yamuna Kalyani raga, which is still performed by classical musicians. It was Vyasatirtha who gave Thimmappa Nayaka the name Kanakadasa.

Udupi was one of the epicenters of Vaishnavism. One time when visiting his teacher, Kanakadasa went to the Udupi Sri Krishna temple for worship. Despite Vyasatirtha’s requests, he was not allowed entrance, as he belonged to a lower caste. With determined devotion, Kanakadasa sat outside fervently singing poems in praise of Lord Krishna. Suddenly, the outer wall of the temple cracked open and the installed murti of Krishna turned westward to face Kanakadasa—such that Kanakadasa could have darshan of the Lord! Stunned and overwhelmed, Kanakadasa offered heartfelt prayers to the Lord. To this day, there is a small window called Kanakana Kindi through which devotees come to get a glimpse of Lord Krishna, like Kanakadasa did, before entering the temple. This popular legend gets retold to attest that all people are equal in the eyes of God, and what counts most is the devotee’s faith, surrender and purity of heart.

Vyasatirtha once questioned his students, asking who among those present could attain liberation. Kanakadasa responded in clever wording that none of them could do so. His fellow scholars were inflamed by his apparent arrogance, taking his words to mean that only he would be liberated—none other, not even his teacher! Vyasatirtha, however, understood Kanakadasa’s intent. The phrase he used loosely translates to “I will go (to heaven) if my-self (selfishness) goes (away).” This contains a deep Vedantic truth: only one who has lost the “I” (ego) can attain liberation.

Kanakadasa composed many poems with powerful social messages, promoting the cause of equality for all. Today, musicians have access to around 240 of his songs (Kirtane, Ugabhogas, padas and mundiges), in addition to his major works, such as Haribhaktisara (core of Krishna devotion), Narisimhastava (compositions in praise of Lord Narasimha), and Ramadhanyacharite (story of ragi millet). Kanakadasa’s songs stress cultivating good moral values and devotion to the Supreme. His signature (ankita), appearing in the last verse of every composition, is Adikeshava, a remembrance and dedication to his favorite form of Vishnu.

Kanakadasa is believed to have spent his final days in Tirupati, the famed abode of Lord Venkateshwara. In current times, Kanakadasa Jayanti, his birth anniversary, is honored as an official state holiday and is grandly celebrated by thousands in Bada village. A Sri Krishna temple there enshrines a murti of his family Deity, Adikeshava of Kaginele, as well as a bronze of Kanakadasa. The Karnataka state government has created a magnificent Vijayanagara-style fort near Bada with a life-sized golden-colored statue of Kanakadasa as a warrior on horseback. Inside the fort is a majestic palace with a gigantic statue of the saint, as well as beautiful paintings and sculptures depicting episodes from his life and times.

Kanakadasa and the other Haridasas, including his famous contemporary Purandara Dasa, are a major influence on Kannada Vaishnava devotional literature to this day. Their unified voice powerfully promulgated the dvaita philosophy of Madhvacharya. Their philosophical, intuitive and experiential approach to the Divine was influenced by Virasaiva poet-saints of the region, such as Basavanna, Akka Mahadevi and Allama Prabhu, as well as by the Tamil Alvars.

Testimony from a Devotee

“I’ve enjoyed singing his kritis at the Maryland Shiva Vishnu Temple’s annual Haridasa Aradhana festival celebrating all the saints in the Haridasa movement. In Kanakadasa’s compositions, he tries to change people’s attitudes such that they treat everyone equally.”

JAYA BALA, CARNATIC VOCALIST & INSTRUCTOR, SAN JOSE, USA

LEARN MORE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Watch “Bhakta Kanakadasa” film (1960)

Visit Udupi Sri Krishna Temple and Kanakana Kindi (Kanaka’s Window)

Read Mystic Tradition in Religion and Art in Karnataka, by M.V. Krishna Rao

Devaranamas of Kanakadasa

Nee Mayeyolago

Are you a creature of illusion? Or is illusion your creation?

Are you a part of the body? Or is the body a part of you?

Is space within the house? Or the house within space? Or are both space and house within the seeing eye? Is the eye within the mind? Or the mind within the eye? Or are both the eye and mind within you?

Does sweetness lie in sugar, or sugar in sweetness?

Or do both sweetness and sugar lie in the tongue?

Is the tongue within the mind? Or the mind within the tongue?

Or are both the tongue and mind within you?

Does fragrance lie in the flower? Or the flower in fragrance? Or do both the flower and fragrance lie in the nostrils? I cannot say, O Lord Adikeshava of Kaginele! O peerless one, are all things within you alone?

TRANSLATION: HTTP://BIT.LY/KANAKADASANEE

Tallanisadiru Kandya

Fret not, O mind! Be patient.

He will protect everyone; there is no doubt about it.

Who was it that tended and watered the tree that grew on a hilltop?

As He is responsible for your existence,

He will certainly look after you; have no misgiving.

Who was it that fed the animals and birds that roam in the forest?

Just like your own mother, He will take the onus to care for you without fail.

Who nourished the worms and insects that were born on a stone?

The lotus-eyed Adikeshava of Kaginele

will protect everyone; there is no doubt about it.

TRANSLATION: CHAKRAVARTHI MADHUSUDANA HTTP://BIT.LY/KANAKADASA

Poonthanam: Kerala, 1547–1640

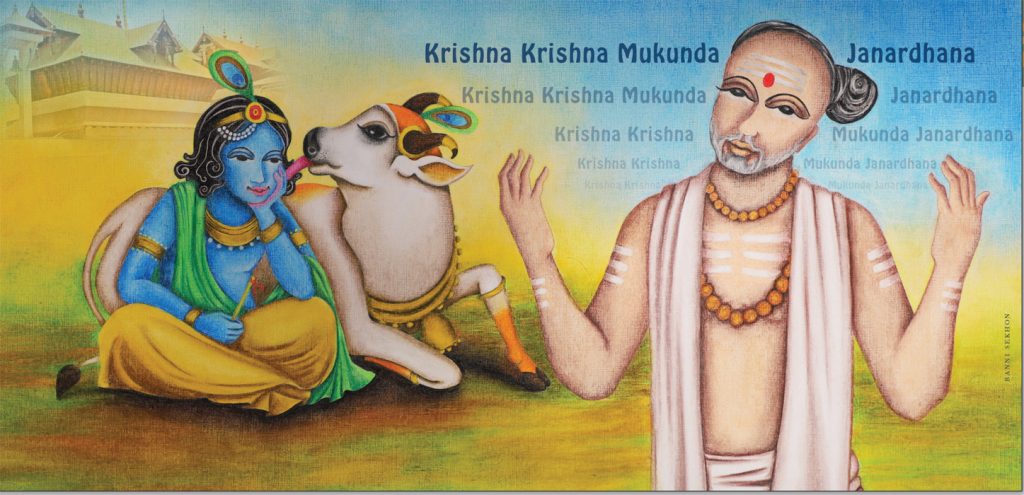

A sacred place is made famous by saintly people who have resided in and propitiated the Deity of that region through their sadhanas and devotional works. Their spiritual example travels far and wide. Guruvayur, the town of the Deity Guruvayurappan, is such a holy place. It is a famous pilgrimage center in Kerala’s Thrissur district, drawing thousands of devotees and revered as Bhuloka Vaikuntha (Lord Vishnu’s earthly abode). Among the many noble souls associated with Guruvayur Temple, where Lord Krishna is worshiped as a little boy, is poet-saint Poonthanam of the 16th century.

Poonthanam was a devotee of Lord Guruvayurappan from childhood. Marrying at age 20, he and his wife were childless for a long time. They sought the grace of Lord Guruvayurappan by reciting “Santhana Gopalam” (a series of mantras traditionally chanted 108 times for 108 consecutive days, while visualizing the baby Krishna). In time a son was born to them in 1586. The overjoyed couple arranged for a grand celebration and invited everyone they knew. But alas, the child tragically died an hour before the ceremony. Shocked and filled with sorrow, Poonthanam sought refuge at Guruvayur Temple. According to legend, he was consoled by Lord Guruvayurappan, who lay in his lap for a moment as baby Krishna. Poonthanam writes in his magnum opus, Jnanappana, “When the divine child Krishna dances in our hearts, is there any need to have little ones of our own?” Thereafter Poonthanam thought of Guruvayurappan as his own child and spent his days in the temple expounding the Lord’s glories.

Bhakti or Vibhakti: Devotion or Scholarship?

One day, Poonthanam went to meet the respected Narayana Bhattathiri, a celebrated devotee of Lord Guruvayurappan. Bhattathiri was a prolific Sanskrit scholar and author of Narayaniyam, a condensed version of Bhagavata Purana. Poonthanam took with him some of his own devotional poetry, written in Malayalam, with the hope that the scholar would read and comment on it. Seeing that the work was in the local dialect and not in Sanskrit, Bhattathiri trivialized Poonthanam’s request and refused to read the proffered poems. Poonthanam left with a heavy heart. In those times, Malayalam was considered inferior to Sanskrit.

That night, Lord Guruvayurappan, touched by Poonthanam’s humility and devotion, appeared in Narayana Bhattathiri’s dreams and declared, “I prefer Poonthanam’s genuine bhakti to your vibhakti (alluding to scholarship).” The next morning, Bhattathiri, chagrined by his pompous blunder, rushed to Poonthanam and sought his forgiveness.

The Jnanappana, “Song of Divine Wisdom”

Employing simple Malayalam, Poonthanam composed many works in praise of Lord Guruvayurappan, such as the Sri Krishna Karnamrtam, Santanagopalam Pana and Anandakarnamritam. Of all his works, his 360-line Jnanappana is considered his masterpiece. Jnana means wisdom, and pāna refers to a style of folk poem or song meter typical of Malayalam poetry. It is admired for its poetic finesse in expressing deep philosophical and devotional messages, while being linguistically accessible to all. Jnanappana is revered as the Bhagavad Gita of Malayalam. It’s said it was composed with the help of Lord Krishna Himself, to embody the essence of the Bhagavatam, the Vedas and the Puranas.

Through his poems, Poonthanam provides ways to make the transient human life meaningful, by elucidating metaphysical truths about the soul’s nature and existence. He encourages all to strive towards liberation (mukti), and points out that bhakti is the easiest way to attain union with God in the Kali Yuga.

The Power of Namasmaranam

Glorifying the names of God is a common practice in many world religions, including Sanatana Dharma. Poonthanam emphasized the power of Namasmaranam (remembrance and repetition of God’s names) throughout his works, as did countless other saints and mystics in the Hindu tradition, from Draupadi and Prahlada, to Mirabai and Thyagaraja. In the Jnanappana, the following verse comprising names of Lord Krishna appears repeatedly. It is traditionally sung as a refrain after every verse in the composition.

Krishna Krishna Mukunda Janardana

Krishna Govinda Narayana Hare

Achyutananda Govinda Madhava

Satchidananda Narayana Hare

Why constantly chant, sing or remember the Lord’s Name? Sage Vyasa affirmed that in the Kali Yuga it is easy to reach God through chanting the Lord’s names. In the 28th verse of Jnanappana, Poonthanam declares that no effort can lead to liberation other than chanting of the divine names Krishna, Mukunda, Janardana, Govinda, Rama, etc. It is believed that in 1640 Lord Guruvayurappan came down to Earth and took Poonthanam to His heavenly abode, Vaikuntha. In contemporary times, devotees celebrate the poet-saint’s life annually at the Guruvayur Sri Krishna Temple on “Poonthanam Day” by reciting his devotional works. During March of each year, a week-long literary festival is held in Poonthanam Illam, the poet-saint’s home.

Testimony from a Devotee

“Poonthanam’s story is very famous in Kerala. His verses are quoted by parents to children. Jnanappana teaches us that God is always within, and God will give what is best for us. We live with that faith.”

RAJI KRISHNAN, 92, CARNATIC VOCALIST & VIOLINIST, COIMBATORE

LEARN MORE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Visit Guruvayur Sri Krishna Temple and Poonthanam Illam in Kerala, India

Read Jnanappana, commentary by Savitri Puram (online)

Listen to “Jnanappana” (Poonthanam’s magnum opus) on YouTube

Verses from the Jnanappana

TRANSLATED BY ANEESH, FROM HIS “TRUE INDOLOGY” BLOG

Gurunathan Thuna Chaika

May the guru bless us to have the holy names of God

on the tip of our tongue forever,

and to chant those auspicious names always,

so as to make this human life meaningful

and to fulfill the purpose of life.

Innaleyolam Enthannarinjeela

We do not know what happened until yesterday,

nor do we know what will happen tomorrow.

We do not know what will happen

to our body in the next moment,

nor do we know when it will perish.

Kandukandangirikkum Janangale

If God wishes, the people we see now or are with us now

may disappear or be dead in the next moment.

Or, if He wishes, in few days a healthy man

may be paraded to his funeral pyre.

If God wishes, the king living in a palace today

may lose everything and end up

carrying a dirty bag on his shoulders

and walk around homeless.