We rarely think about it, but symbols are everywhere around us–potent, poignant images, visual markers for something vitally meaningful to us–a force of nature, a beloved Deity, a dangerous roadway curve. Symbols arrest our awareness, signal a message and draw us to a particular area of consciousness. Most often, symbols convey abstract experience. Of the three depicted above, the first is the element fire, the second a mythic creature representing time, and the third a gesture of humble greeting. These are among dozens of classical icons used in Hindu art and mysticism, reminding seekers of the subtle, spiritual realities of the Sanatana Dharma. ”

Symbols adorn our world and mind at every turn–in our spiritual, social and political experience. A ring or golden pendant serves to silently attest to and strengthen wedded love. On a mountainous road in any country, a sign with a truck silhouette on a steeply angled line warns drivers of dropping grades ahead. The red cross signals aid and comfort in crises. Golden arches tell the vegan to beware. Among the best known symbols in the world are the simple numerals: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9. They originated in ancient India as characters of the Brahmi script. Now and then, historic images or happenings are supercharged into symbols. The awesome mushroom cloud of the atom bomb will forever represent the terrifying specter of nuclear destruction.

It is humanity’s sacred symbols, its icons of Divinity and Reality, that wield the greatest power to inform and transform consciousness. Taoists gazing upon a yin-yang symbol, Navaho Indians delicately pouring a feather symbol in a sand painting, Muslims embroidering the crescent moon and star, Tibetan Buddhists contemplating an intricate mandala, Christians kneeling before the cross, Hindus meditating upon the Aum, Pagans parading the ankh at Stonehenge–all these images, and hundreds more, communicate cosmic belief structures and function as gateways to inner truths.

To the societies of prehistory (ca. 7000-4000 bce), living fully in the raw splendor and power of nature, symbols and icons represented supernatural states and beings–as they still do for us today. A stylized image of a snake coiled around the top of a clay vase communicated a complex and abstract idea. Anthropologist Marija Gimbutas interprets it as cosmic life force and regeneration.

Wielded by mystic priests, or shamans, symbols serve as psychic tools for invoking invisible cosmic beings and shaping the forces of nature. Thus, to conjure power, a medieval alchemist would enclose himself in a magic circle (a worldwide symbol) filled with geometric pictograms symbolizing astral plane realities.

Today, as in prehistoric epochs, religious symbols often draw on nature forces. The sun flares into prominence among these symbols, appearing in a spectrum of motifs across cultures from Mexico to Mongolia. Hinduism developed dozens of solar symbols, including the swastika and the wheel of the sun, adopted by the Buddhists as their eight-spoked dharma wheel.

Hinduism has amassed a range of didactic icons from thousands of years back. Coins found in the Indus Valley have carried the symbols of the cow and of the yogi seated in meditation across a 6,000-year corridor of time. Many images from the Vedic age have become popular motifs in Kashmiri carpets and Chidambaram saris. These serve, significantly, to identify and distinguish members of a sect or community. The simple red dot worn on the forehead of many devout Hindus is both the mark of our dharmic heritage and the personal reminder to all who wear it that we must see things not only with our physical eyes, but with the mind’s eye, the Third Eye.

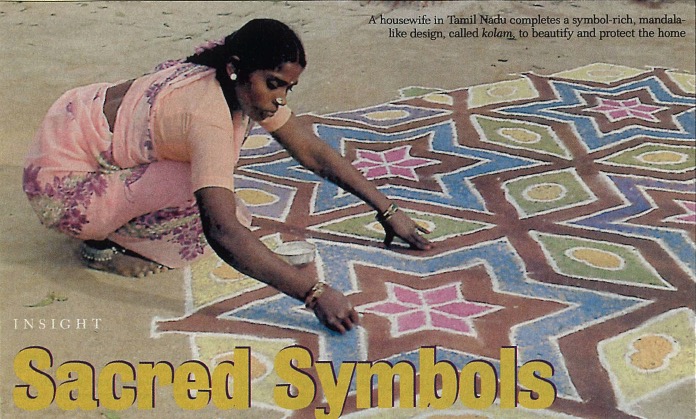

India’s adepts and seers have excelled at symbolic imagery, transforming mudras (hand gestures) into instantly recognized emblems and transmitters of a Deity’s power or a particular frequency of energy. Each accoutrement of the dozens of Deities in the Hindu pantheon conveys a cosmic function, force or capacity. Today, this ancient magic is carried forward in a multitude of ways, from the temple priest’s invocation to the Indian housewife’s drawing of multi-colored designs, called kolams or rangoli, on the ground as auspicious auguries, household blessings and greetings.

Attention Web browsers: You may be interested in picking up a hard copy of the February edition of Hindusim Today. The following descriptions are actually a full 3 page color art presentaion and guide to the ancient symbols of Hinduism.

Ganesha is the Lord of Obstacles and Ruler of Dharma. Seated upon His throne, He guides our karmas through creating and removing obstacles from our path. We seek His permission and blessings in every undertaking. Aum.

Gopuras are the towering stone gateways through which pilgrims enter the South Indian temple. Richly ornamented with myriad sculptures of the divine pantheon, their tiers symbolize the several planes of existence. Aum.

Pranava Aum is the root mantra and soundless sound from which all creation issues forth. It is associated with Lord Ganesha. Its three syllables stand at the beginning and end of every sacred verse, every human act. Aum.

Swastika is the symbol of auspiciousness and good fortune–literally “It is well.” The right-angled arms of this ancient sun sign denote the indirect way that Divinity is apprehended: by intuition and not by intellect. Aum.

Sri Chakra yantra is central to Shakta worship and meditation. Often rendered in three dimensions in stone or metal, its nine interlocking triangles represent Siva-Shakti’s multidimensional manifestations. Aum.

Gaja is the elephant, king of beasts and sign of royalty and power. He is Indra’s mount, denoting the dominion of Heaven’s King. In larger Hindu temples and elaborate festive pageantry there is always a noble elephant. Aum.

Padma is the lotus flower, Nelumbo nucifera, perfection of beauty, associated with Deities and the chakras, especially the 1,000-petaled sahasrara. Rooted in the mud, its blossom is a promise of purity and unfoldment. Aum.

Nandi is Lord Siva’s mount, or vahana. This huge white bull with a black tail, whose name means “joyful,” is disciplined animality kneeling at Siva’s feet, the ideal devotee, the pure joy and strength of Saiva Dharma. Aum.

Vata, the banyan tree, Ficus indicus, symbolizes Hinduism, which branches out in all directions, draws from many roots, spreads shade far and wide, yet stems from one great trunk. Siva as Silent Sage sits beneath it. Aum.

Kalachakra, “wheel, or circle, of time,” is the symbol of perfect creation, of the cycles of existence. Time and space are interwoven, and eight spokes mark the directions, each ruled by a Deity and having a unique quality. Aum.

Shikhara is the massive stone superstructure which rises above the cave-like sacred sanctuaries of temples in North India. It is a living model of Mount Meru, the center of the universe where the Gods themselves reside. Aum.

Mudras are hand gestures employed in sacred dance and puja to focus the mind on abstract matters and to charge the body with spiritual power. This is chinmudra, the gesture of realization, reflection and silent teaching. Aum.

Trishula, Siva’s trident carried by Himalayan yogis, is the royal scepter of the Saiva Dharma. Its triple prongs betoken desire, action and wisdom; ida, pingala and sushumna; and the gunas–sattva, rajas and tamas. Aum.

Tulsi is the holy basil plant, Ocimum sanctum, sacred to Vaishnavites. Prayer beads are made from its wood or smooth seeds, and the shrub is worshiped in the home as Lakshmi, bringing prosperity, protection and long life. Aum.

Sivalinga is the ancient mark or symbol of God. This elliptical stone is a formless form betokening Parasiva, That which can never be described or portrayed. The pitha, pedestal, represents Siva’s manifest Parashakti. Aum.

Kukkuta is the noble red rooster who heralds each dawn, calling all to awake and arise. He is a symbol of the imminence of spiritual unfoldment and wisdom. As a fighting cock, he crows from Lord Skanda’s battle flag. Aum.

Shatkona, “six-pointed star,” is two interlocking triangles; the upper stands for Siva, purusha and fire, the lower for Shakti, prakriti and water. Their union gives birth to Sanatkumara, whose sacred number is six. Aum.

Dipastambha, the standing oil lamp, symbolizes the dispelling of ignorance and awakening of the divine light within us. Its soft glow illumines the temple or shrine room, keeping the atmosphere pure and serene. Aum.

Amra, the pleasing paisley design, is modeled after a mango and associated with Lord Ganesha. Mangos are the sweetest of fruits, symbolizing auspiciousness and the happy fulfillment of legitimate worldly desires. Aum.

Shankha, the water-born conch, symbolizes the origin of existence, which evolves in spiraling spheres. In ancient days it signaled battle’s victory. In the Lord’s hands it is our protection from evil, sounding the sacred “Aum.”

Chandra is the moon, ruler of the watery realms and of emotion, testing place of migrating souls. Surya is the sun, ruler of intellect, source of truth. One is pingala and lights the day; the other is ida and lights the night. Aum.

Rudraksha seeds, Eleocarpus ganitrus, are prized as the compassionate tears Lord Siva shed for mankind’s suffering. Saivites wear malas of them always as a symbol of God’s love, chanting on each bead, “Aum Namah Sivaya.”

Urdhvapundra is the royal mark upon the forehead of Vaishnavites. Two white lines are Vishnu’s foot print resting upon a lotus base. The red represents Lakshmi. Thus, the Lord’s lowest part is worshiped on our highest. Aum.

Shula, Lord Murugan’s holy lance, is His protective power, our safeguard in adversity. Its tip is wide, long and sharp, signifying incisive discrimination and spiritual knowledge, which must be broad, deep and penetrating. Aum.

Trikona, the triangle, is a symbol of God Siva which, like the Sivalinga, denotes His Absolute Being. It represents the element fire and portrays the process of spiritual ascent and Liberation spoken of in scripture. Aum.

Shri paduka, the sacred sandals worn by saints, sages and satgurus, symbolize the preceptor’s holy feet, which are the source of his grace. Prostrating before him, we humbly touch his feet for release from worldliness. Aum.

Go, the cow, is a symbol of the earth, the nourisher, the ever-giving, undemanding provider. To the Hindu, all animals are sacred, and we acknowledge this reverence of life in our special affection for the gentle cow. Aum.

Kamandalu, the water vessel, is carried by the Hindu monastic. It symbolizes his simple, self-contained life, his freedom from worldly needs, his constant sadhana and tapas, and his oath to seek God everywhere. Aum.

Naga, the cobra, is a symbol of kundalini power, cosmic energy coiled and slumbering within man. It inspires seekers to overcome misdeeds and suffering by lifting the serpent power up the spine into God Realization. Aum.

Kalasha, a husked coconut circled by five mango leaves on a pot, is used in puja to represent any God, especially Lord Ganesha. Breaking a coconut before His shrine is the ego’s shattering to reveal the sweet fruit inside. Aum.

Bilva is the bael tree. Its fruit, flowers and leaves are all sacred to Siva, Liberation’s summit. Planting Aegle marmelos trees around home or temple is sanctifying, as is worshiping a Linga with bilva leaves and water. Aum.

Ankusha, the goad held in Lord Ganesha’s right hand, is used to remove obstacles from dharma’s path. It is the force by which all wrongful things are repelled from us, the sharp prod which spurs the dullards onward. Aum.

Mushika is Lord Ganesha’s mount, the mouse, traditionally associated with abundance in family life. Under cover of darkness, seldom visible yet always at work, Mushika is like God’s unseen grace in our lives. Aum.

Homakunda, the fire altar, is the symbol of ancient Vedic rites. It is through the fire element, denoting divine consciousness, that we make offerings to the Gods. Hindu sacraments are solemnized before the homa fire. Aum

Mahakala, “Great Time,” presides above creation’s golden arch. Devouring instants and eons, with a ferocious face, He is Time beyond time, reminder of this world’s transitoriness, that sin and suffering will pass. Aum.

Anjali, the gesture of two palms pressed together and held near the heart, means to “honor or celebrate.” It is our Hindu greeting, two joined as one, the bringing together of matter and spirit, the self meeting the Self in all. Aum.