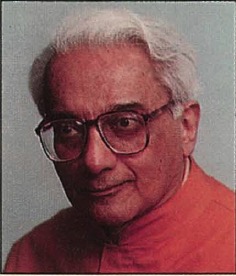

BY SWAMI SHIVAPREMANANDA

All Hindus have a moral and spiritual obligation to remind themselves of their cultural heritage in the Vedas and be proud of it, while rising above sectarian narrow-mindedness. Being in the West for the past thirty-six years, I am more and more aware of this deficiency among many of those who are born in the Hindu tradition, and specifically so at all levels of the Indian diplomatic corps.

After independence, in 1947, the Indian government’s policy became biased in favor of a half-baked, distorted form of secularism, when just the sense of being a Hindu became something to be reticent about among the third-rate imitation of Westernized intelligentsia. It still persists. There cannot be a more secular nation than Britain or the United States. Yet, the British are not ashamed to call themselves a Christian nation, where many other faiths flourish in liberty–the Queen still being the defender of the Anglican faith. Americans are not ashamed of their Biblical heritage, while many other faiths thrive within its fold. They are not ashamed to print and emboss on their currency the motto, “In God We Trust.”

No other faith is more tolerant of other faiths than Hinduism. Even before the incursion of Islam’s conquering violence in Northwest India, in the Southwest Islam was welcomed as the religion of Arab traders. In the first century of this common era, Christianity found its place in Southeast India, long before the onset of Catholicism and the violent impact of the Portuguese. Desperate for its survival and to hold back the onrushing tides of a totally alien, iconoclastic culture, Hinduism raised its sectarian walls and slid into decadence with the passing of the centuries. It is, thus, time to remind ourselves of our roots.

The Vedas are the earliest spiritual literature in history. They have greatly influenced the Hindu view of life. The word is derived from the root vid, to know. Knowledge has two sides, 1) empirical and 2) the pertinence of the material reality, with an infinite possibility of widening understanding. Hinduism’s basis is to regard the world as a stage on which human beings act out a morality play, the purpose of which is to overcome suffering and be happy, happiness being the innate nature of the spirit (ananda) embodied in an inadequate vehicle, living in an imperfect world. Freedom of the soul from material bondage is the spiritual goal, and its merger in the transcendental spirit (Brahman) the common destiny. This freedom is attained through devotion to one’s inner spirit (atman or God), knowledge of the various truths of existence and by leading a life of self-discipline and self-improvement.

Life suffers when it is led by the blind force of impulses and mundane desires. The purpose of religion is to understand, educate and sublimate them. This is done by the cultivation of a moral sense and its application in daily life through practicing the following spiritual ideals: 1) Purity of heart, or that which is free from hate, malice, resentment, vengeance, avarice, wickedness and imputing bad motives to others; 2) Unselfish love, spontaneous compassion and kindness to and consideration of others, with matching deeds; 3) Integrity of feeling or depth of sentiment–rather than sentimentalism–of thinking, of expression through speech and action, and honesty to oneself and to others; 4) Sublimation of passions and worldly desires; 5) Purification of the ego toward humility of spirit and genuine modesty.

Vedanta represents the essence of Hinduism. As the word implies, it is the culmination or conclusion (anta) of the Vedic teachings, consisting of the Upanishads. More than a thousand years before the common era, Krishna Dvaipayana Vyasa interpreted them in his Brahmasutras and, in the name of Sri Krishna, in the Bhagavad Gita. In the history of civilization, no other teachings have expressed such a positive, unifying spirit of reconciliation. By the vision of monism, making God a transcendental, all-pervading spirit–rather than a singular, all-important and the only valid deity, as in monotheism–it took away the inherent sting of intolerance and iconoclasm. Judaism, Christianity and Islam have a lot to learn from it, as all religions should learn from one another the best in each other.

The immensely broad vision of Vedanta is expressed in the following ways. Brahman or the Supreme Being is not a deity or a substance than can be confined within a conceptual image, but is an immanent spiritual presence in creation, while being transcendental. Even though God cannot be defined, the human spirit can relate to the indefinable through spiritual ideals qualified by the adjectives to rise above qualification: infinite, to expand them constantly; eternal, to provide the security of permanency; universal, to have the relevancy among all, irrespective of religious or cultural backgrounds; and transcendental, in order to realize them better. The mantra sha vasyam idam satvain in the Isha Upanishad, that “all is pervaded by the infinite spirit,” created for the first time in the human consciousness a sense of sanctity for all forms of life, not only for humankind, and not merely confined to one’s own tribes, but respect for animals and nature as well. The three monotheistic religions–Judaism, Christianity and Islam–uphold God as the transcendental creator, but the Brahman of Vedanta, while being transcendental and unaffected, is also immanent in the universe.

SWAMI SHIVAPREMANANDA,72, was private secretary to Swami Sivananda, taught Yoga-Vedanta in Rishikesh and now directs large centers in South America–namely Argentina, Uruguay and Chile.