“I am of the opinion that religious people have the courage to face the world positively,” said Shri Kishore Tripathy of Cuttack in the West India state of Orissa. Tripathy, a newspaper manager, is a member of India’s emerging middle class. As for the middle class worldwide, religion is important to him, but not in the form it is followed by his parents and grandparents. Because of secular education, television, foreign influence, travel and a less restricted life style, Bharat’s middle class is less inclined to the magic and ritual dear to earlier generations–though hardly willing to relinquish Hinduism’s frequent festivals. They are religious for the most part, even deeply so, but tend toward a more intellectual and inwardly meditative experience of faith.

Two-hundred million mostly urban-dwelling Indians of all religions and all castes whose income levels are reaching and surpassing one lakh rupees a year (US$2,800) comprise Bharat’s burgeoning middle class. It is the largest reshaping of the country’s social structure since the British attempted through Lord Macauley’s education program to create a class of Indians who would stand between the masses and their British rulers. That group still exists–English in all their arrogant aspects except appearance. They are anachronisms, intellectual clones of people rarely found in England any more, engaged in disparaging any and all things Indian while lauding all things Western. India’s new middle class differs from Macauley’s minions. Especially, they are Indian. To a significant extent they have seen through and rejected the anti-religion beliefs of the communists, rationalists and secularists. This is in keeping with religious tendencies of the middle class in most industrialized countries [see sidebar below].

To explore the religious life of this growing middle class community–almost the population of the United States and increasing at the rate of ten percent a year–hinduism today correspondents across India conducted a survey. They asked Mr. Tripathy in Orissa, Mrs. Rajaram in Delhi, Mr. Matthew in Kerala, Mrs. Jain in Bangalore and their friends and neighbors about their personal religious life, whether they were more or less religious than their parents, how they were educating their children in religion and their general observations on the middle class. Our study is not scientific, and the responses by no means uniform, but general trends are seen.

By Mangala Prasad Mohanty, Delhi

I feel that not believing in god is a temporary phase,” continued the insightful Tripathy. “In Orissa, with the increase in education and wealth, the religious feelings are growing. People are offering financial support for the construction of temples and vigorously observing rituals and festivals. My entire family regularly worships Lord Ganesha. I teach my children that religious people are decisive, they progress in life, they offer everything to God and owe it to Him. Not that all religious people are successful in life, but they are not unsuccessful. Non-followers lack direction in life. The essence of religion is in the principles, not the rituals.”

The adjacent state of West Bengal has had a communist government for years, but, points out M.C. Bhandari of Calcutta, “Every year people celebrate Kali puja and other festivals in a large way, despite the ruling Communist Party influence. It is a contradiction between faith and politics.” Even here, in the stronghold of India’s communist ideologists, an atheistic middle class has not emerged. Bhandari is president of Bharat Nirman, an organization founded to bring a revival of the Indian way of life.

In response to questions about his family, Bhandari said, “I strongly feel that the youngsters should grow according to their own talent and aptitude, and your own life should be such that they can learn from your conduct and behavior rather than on your instruction and imposition.”

Religion is central to the life of Bidhan Das, a doctor at the Jain medical centre in New Delhi. “I am optimistic about the growth of religious practices among the middle class and others,” he told Hinduism Today. “I see that everybody, including doctors, are God-fearing people. We may not be observing all the rituals, due to shortage of time, nuclear family, working wife, etc., but we are religious. For example, before making an incision in surgery, I and nearly every doctor will say, ‘By the name of the all mighty God.’ Daba and dua (medicine and blessings) go hand in hand. We are mere messengers of healing.”

Srimati Janaki Rajaram is a native of South India, now a housewife and woman’s rights activist in Delhi. “In the cities,” she said, “because of the fast life style, workload, culture of money, children’s study, ladies working, children playing on computers, adults attending parties, going to clubs, watching TV, there is no time left for puja and observance of rituals and other practices. Nowadays parents have to devote more time to children, thus the religious practices are in decline.”

But for her personally, like many of the brahmin class, home religious life is strong. She is quite forthright about a woman’s religious responsibility. “At home,” she said, “because of timing and capacity, women do a lot of the worship. Every day in the early morning, I perform worship by chanting prayers in Sanskrit, which I am also teaching to my granddaughters. I and all members of my family offer flowers, fruits and milk with honey to God and light the sacred lamp. In most middle-class families, at least some members offer daily puja.”

V.S. Gopalakrishnan, Kerala

The middle class in Kerala is different than in other parts of India, for it is the influx of money from expatriate workers in the Gulf states which has created the group here, not so much a local economic boom, as in the rest of India. Kerala is different, too, for its history of extensive Christian conversion, its decades of communist rule and its 100 percent literacy rate. Among the religious community, more Christians and Muslims, proportionate to their populations, have landed Gulf jobs. As in Bengal, communist rule doesn’t ensure an atheistic population, though here in Kerala Hindus who support the communists tend to be almost religion-less, while Christians and Muslims who support the communists politically remain staunchly religious.

The emerging Christian and Muslim middle class is enjoying an unprecedented improvement in their standard of living and becoming more religious, too. Once mass was conducted in the Catholic churches only on Sundays. Now it is done almost every day. Mr. Matthew, a tailor, explained why he was a regular churchgoer, “It is the only place where we could gather and have some peace of mind after the work.” Mr. Sam, also a Christian, felt he should regularly offer his gratitude, “We should not forget God when we prosper day after day. Religion is the thread which keeps us together.” The opinion of Mr. Latif, a Muslim, and his friends echo these thoughts. Many Muslim women are now wearing the veil, which Latif regards as “clear indication of how religious we Muslims are”–and can also be attributed to contact with the far more conservative Muslims of the Gulf states. Another indication of the religiosity of both communities is that there is no dearth of Muslim and Christian boys volunteering to become priests, while the Hindu community actively discourages its youth from such a life.

Middle class Hindus in Kerala interviewed by Hinduism Today revealed religion to be much less important in their lives than it was in the lives of their Christian and Muslim neighbors. They unanimously said they do not read any of the scriptures. In the evening, they never recite hymns at home after lighting the traditional oil lamp. Instead, television provides the main activity–something observed throughout India. In fact, one can postulate that it is television which has replaced ritual observance in many Hindu homes.

The strength of the Muslim and Christian faiths in Kerala has not gone unnoticed by the middle class Hindus. Improbable for a religious culture measured in millennia, it is now from the example of these other faiths that Hindus are waking up to the need for religion. Mr. Divakaran said, “Having seen the progress of the Christians and Muslims as strong communities, socially, economically and religiously, we feel that our kids should be taught about our religion.”

Choodie Shivaram, Bangalore

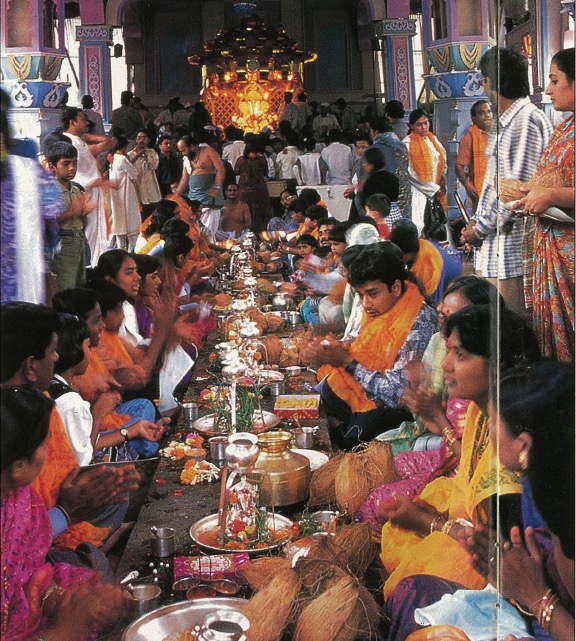

Special home worship ceremonies to the Goddess, vrats, have become a kind of fad amongst Bangalore’s middle class. A recent example of this combined ritual and social occasion is the “Aishwarya Lakshmi Puja” in which the lady of the house worships Goddess Lakshmi for prosperity on Friday evening with her lady friends, to whom she gives gifts and a book detailing worship of the Goddess. Those attending can, if so inspired, use the book to repeat the puja in their own home. Other forms of group worship, both at home and temple, are popular with the middle class.

Here is a glimpse into my own personal experience, as an example of how the meaning of religion has been transforming itself in recent generations. My grandmother was intensely religious, very orthodox. As a child, I enjoyed this religiosity because it meant more people at home, a celebrative mood and the tasty food offerings. But as I grew and saw my mother’s ritualistic religiosity, I found it boring and at times painful. I began questioning the meaning and significance underlying these pujas, but the answers given did not convince me. Now I understand religion in a different sense. I do not believe in pujas and elaborate worshiping. I pray, more often I converse with God. I look at Him as a father, a friend and guide. That’s my religion.

Indira Yesupriya, an employed Christian lady, considers herself more religious than her parents, who were more ritualistic. She is, however, very clear on the necessity of religion in her life. “I follow religion as a way of life just like the way we breathe,” she said. “To me, it’s natural. I don’t go to church regularly or read the Bible or any religious texts. Religion gives you something serious to fall back upon. All religions teach the same thing, to be good, just, fair. Our children will be better citizens of the world if we teach them the right way to religion.”

“I’m less religious than my parents,” admitted Mrs. Jain, a teacher and Bangalore resident. “My mother had more time to devote to religion; her way of being religious was more through pujas. While we think logically now, they would never question. To me, religion gives you the faith that if there is no one for you, still there is God who will be with you. Being inhuman and nasty to others and praying to God does not mean religion.”

“My way of religion is through work,” offered Mrs. Jayashree Dandi, a Bangalore musician, “I’m sincere in my work and my prayer is in that. I have made sure that I have inculcated religious values in my children by teaching them right values, respecting elders, being harmless to others, not being rude or arrogant. Religion gives you a conscience.”

Madhavan, an employee in a private firm, said, “I have tried to get down to the essence of Hindu philosophy and pass it on to my children so that they understand the real meaning of the religion and not the superficial aspect through rituals, as we did. Once we understand the significance behind each festival, it’s very meaningful. Impressing a correct value system in our children is most important if we desire to contribute to the world some worthy citizens. Religion is the only real source for inculcating this value system.”

Clearly religion has not been dismissed from the lives of India’s middle class. Indeed, it is central to most. The same situation is found in America and other industrialized countries–growing affluence does not diminish religiosity, as many presume. This middle class is seeking a different form of religion, one which is to them logical, provable, scientific even, one which is not so much a matter of outward form, but of inward closeness to God. They are uncomfortable with the ritual potencies which guided, enhanced and protected the lives of their parents. They are unable, it seems, to feel the very real contact between the human world and God’s world which is facilitated by ritual. Perhaps this trend away from ritual and religious texts is explained by the modern secular education system and its related values and social matrix which created this middle class of lawyers, scientists, engineers and entrepreneurs. Fortunately, Hinduism has little trouble accommodating a ritual-less devotee, for there are entire branches of orthodox Hindu philosophy and practice which reject ritual. One need only reference the commonly available Upanishads for a road map to God within.

Two obstacles appear to inhibit middle class faith. One is foreign concepts about religion such as the view that “Religion is the opium of the masses,” and that “faith in rituals is based on fear and superstition” and “swamis and gurus are unnecessary.” The first is a Marxist teaching. The others derive from Protestant Christian rejection of ritual worship and priesthood as found in Catholicism. The second obstacle is religious education. In India, Christians and Muslims have comprehensive systems to educate their youth; Hindus have almost nothing. Previously Hindu religion was taught in the context of the joint family; today’s nuclear family is too busy. Programs must be developed and taught by various Hindu institutions. Parents must recognize the changing circumstances, understand the need for a systematic religious education and send their children for regular, religious instruction from an early age right through their teens. Then a firm and solid foundation of ethics, morals and intelligent religiousness will be instilled in generation after generation of Hindu children.

RELIGION, AMERICAN STYLE

WHERE INDIA’S MIDDLE CLASS MIGHT BE HEADED

George Gallup is the man who takes the religious pulse of America. He is more famous for “Gallup Polls” that predict election results upon which many a politician’s dreams die long before election day. But his Princeton Religion Research Center in New Jersey has a divine mission–to provide an in-depth profile of the religious beliefs and practices of Americans. His insights into religious beliefs and attitudes are useful in understanding both the present and likely future religious disposition of India’s middle class.

Given their affluence and worldliness, Americans are surprisingly religious–only four percent are atheists, while 96 percent believe in God or a universal spirit; nine in ten consider religion “very or fairly important in their lives.”

PRRC’s 1996 report, “Religion in America,” posits three “gaps”–each of which finds parallel in India. First, there is the “ethics gap”–the difference between the way the people think of themselves and the way they are. Despite religion’s popularity, evidence suggests that it does not change the lives of Americans to the degree one would expect from the level of faith professed–a problem echoed in India’s struggle with corruption. Second, there is a “knowledge gap”–the breach between Americans’ stated faith and their lack of the most basic knowledge about that faith. Middle-class Hindus complain of the same lack of basic knowledge. Finally, there is a growing “gap between believers and belongers”–a decoupling of belief and practice. Millions of all faiths are believers, many devout, but they do not participate in denominational organizations.

Americans, like many middle-class Indians, tend to view their faith as a matter between themselves and God, to be aided but not necessarily influenced by religious institutions. They believe, according to PRRC research, that people should arrive at their religious beliefs independently of any church, and that it does not make any difference which church a person attends because one is as good as another.

A CAPITAL PICTURE SHOW

Raghu rai’s Delhi is a delightful pictorial slice of life of India’s capital city. Rai, born in 1942 in Punjab, is one of India’s most distinguished photographers. The middle class is not the central theme of this large-format book–the city and all her people are–but one would have to search for a more insightful pictorial portrayal of the bourgeoisie.

The beginning photos are black and white, conveying the Delhi of several decades ago when push carts, ox carts and cycle rickshaws were only beginning to compete with Tata trucks and three-wheelers. With characteristically sly humor, Rai transits from past to present and black and white to color with a photo of a farmer ploughing his fields by oxen with an Air India 747 behind him on one page and on the next a color photo of a cow upon a Delhi traffic island casually observing a passing businessman. The subjects range from children playing in the monsoon-flooded streets to political rallies and lawn parties. Hindus celebrate Holi by covering everyone and everything in sight with colored powders, Muslims attend a mosque, and Buddhists ferry a huge statue of Buddha across a field.

The long introductory text by Pavan K. Varma tells the story of Delhi from ancient times to the present in truly exquisite prose.

Harper-Collins Publishers, 7/16 Ansari Road, New Delhi 110 002, India