Sanjeev Sanyal’s fast-paced book, The Land of Seven Rivers, is a provocative portal to Bharat’s history from the time of Pangaea to the 21st century

Sanjeev Sanyal challenges the modern claim that India was never a nation but was born in 1947 as a cobbled-together group of princely states. Some criticize Sanyal’s work for lacking depth. But he doesn’t claim to address all controversies regarding the ancient past of the Indian sub-continent, cover every angle or even include more than a small percentage of his research. He targets the YouTube generation with a fast-paced, story-telling documentary style. In just 300 pages he takes us from the age of Pangaea to the spectacular new city of Gurgaon, with a diverse selection of fascinating subplots that all point to a common theme: India’s nationhood is 8,000 years old, has re-awakened and is moving dynamically into the 21st century. The following text is drawn entirely from his book, mostly from the first half.

THIS BOOK IS ABOUT THE HISTORY OF India’s geography. Although I do not have any formal training as either a historian or as a geographer, my profession as an economist, my love of old maps and wildlife, my studies of urban habitats and my many travels through India and Southeast Asia began to slowly fit together into a mosaic. It was no easy journey. I read through ancient religious texts, the writings of medieval travelers and scores of academic papers on seemingly unrelated and arcane topics. The topic became an obsession. It drove me to take two and half years off from my career to travel around India. Many of the texts make sense only if one has actually visited the places to which they refer.

As we make our way through the second decade of the twenty-first century, India is undergoing an extraordinary transformation. After centuries of relative decline, the Indian economy is reasserting itself. The result is an urban construction boom that defies imagination. As urbanization and modernization churn the population, communities are being torn apart, and with them we are losing old customs, traditions and oral histories. Many reminders of the country’s history are being paved over by new highways and buildings. In a time of rapid change, it is important to remember that India is an ancient land.

Almost all written Indian history to date is concerned with sequences of political events. This book focuses on a somewhat different set of questions: Is there any truth in ancient legends about the Great Flood? Why do Indians call their country Bharat? What do the epics tell us about how Indians perceived the geography of their country in the Iron Age? How did the Europeans map India? And more. One cannot understand the flow of Indian history without appreciating the drying up of the Saraswati river, the monsoon winds that carried merchant fleets across the Indian Ocean, the Deccan Traps that made Shivaji’s guerilla tactics possible.

The very idea of India, its physical geography and its civilization, has evolved over the centuries. Yet, despite all these changes, it is astonishing how India’s civilizational traits have survived over millennia. The ox-carts of the Harappan civilization can still be seen in many parts of rural India, essentially unchanged but for the rubber tyres. The Gayatri Mantra, a hymn composed over four millennia ago, is chanted daily by millions of Hindus. This is not just about longevity but about a civilizational ability to take along an incredible mix of ideas, cultures and lifestyles that, despite their apparent differences, are still a part of the overall patchwork.

One of the persistent misconceptions about India is an idea often repeated by colonial-era officialdom for obvious political ends. As Sir John Strachey put it in the late nineteenth century, “The first and most essential thing to learn about India is that there is not, and never was an India.” Half a century later, Winston Churchill would echo the same point when he said that “India is a geographical term. It is no more a united nation than the equator.” A corollary to this point of view was the argument that since Indians were never conscious of their nationhood, they did not care for their history (or their freedom).

As we shall see, this is totally incorrect. There is more than enough evidence to show that Indians have long been conscious of their history and civilization. Indeed, from very ancient times, Indians have gone out of their way to record their times as well as to create linkages to those who came before them. This sense of civilizational continuity is so strong that foreign rulers, including the British, have repeatedly acknowledged Indian civilization even as they have tried to give themselves legitimacy. But to understand India, we must go back to the very beginning.

Ancient Tectonics and Genetics

After breaking apart from the ancient supercontinent of Pangaea, the Indian subcontinent moved north 55-60 million years ago until it collided with the Eurasian plate. The process is not over—the Indian plate is still pushing into Asia, making the Himalayas and the subcontinent tectonically very active. Wedged into Asia along the Himalayas, the stage was set for the formation of the youngest of India’s geological features—the Gangetic plains. They started out as a marshy depression running between the Himalayas and an older mountain range called the Vindhyas. Silt brought down by the rivers began to create a fertile alluvial plain. We know that the Ganga repeatedly changed its course and shifted southward over time.

After the mysterious global extinction event that occured around 72,000 bce, African Bushmen were the only hominids to survive. With Europe still uninhabitable, locked in ice, a small number, perhaps a single band, crossed over from Africa into the southern Arabian peninsula. They spread out along the Makran coast into the Indian subcontinent. Amazingly, all non-Africans are descendants of this tiny group of wanderers. There are plenty of remains of these early humans in Stone Age sites scattered across India. Bhimbetka in central India is one of the most extensive sites in the world. The hilly terrain is littered with hundreds of caves and rock shelters that appear to have been inhabited almost continuously for over 30,000 years.

Bhimbetka’s cave paintings provide intriguing glimpses of the ancient origins of Indian civilization. As the BBC’s Michael Wood puts it, “Looking at the dancing Deity at Bhimbetka with his bangles and trident, one can’t help but recall the image of the dancing Shiva.” The story is still unfolding, but we know for sure that India supported a fairly large human population by the end of the Neolithic age (circa 4,500 bce). Who were these people? How are they related to present-day Indians?

Until the early twentieth century, it was believed that India was inhabited by aboriginal stone-age tribes until around 1500 bce, when Indo-Europeans called “Aryans” invaded the subcontinent from Central Asia with horses and iron weapons. This theory, however, had to be drastically revised when remains of the sophisticated Harappan civilization were discovered. They proved that Indian civilization clearly predated 1500 bce. Twenty-first-century genetic studies of India’s population are still evolving, but a 2006 study concludes that India’s population mix has been broadly stable for a very long time and that there has been no major injection of Central Asian genes for over 10,000 years. After thousands of years of mixing, Indians are most closely related to each other, and it is pointless splitting hairs over who is more Aryan and who is more Dravidian. The story of Manu, the Indian Noah, sums up the genetic findings surprisingly well. He was said to have been the king of the Dravidians prior to the flood but is repeatedly mentioned in the Vedic tradition as an ancestor!

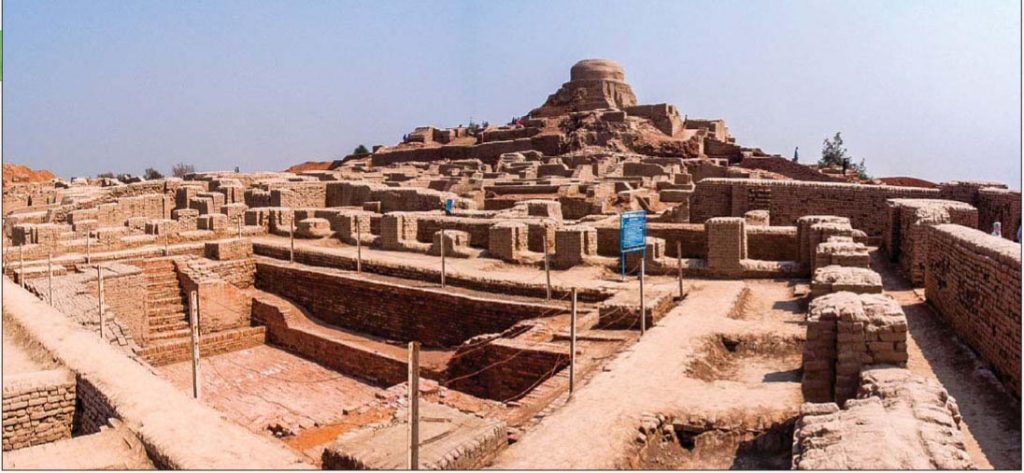

The Story of the Harappans

The hot topic of reconciling the Indus Valley civilization with Vedic tradition often deteriorates into a political debate. The discovery of the Harappan civilization, which was a contemporary of the Sumerians, the Minoans and the ancient Egyptians, revealed no massive structures like the pyramids. Yet, the Harappan sites are remarkable for their attention to urban design and active municipal management. A large city like Mohenjodaro (now in Pakistan) may have had a population of around 40-50,000 people. Furthermore, we see meticulous town-planning in every detail—standardized bricks, street grids, covered sewerage systems, advanced toilets and extensive water management systems and so on. Over the last century, thousands of sites have been found and several new sites are being discovered every year. It appears that the subcontinent was very populous. The core of the Harappan civilization extended over a large area, from Gujarat in the south, across Sindh and Rajasthan and extending into Punjab and Haryana, as far east as Uttar Pradesh and as far west as Sutkagen-dor on the Makran coast of Baluchistan, not far from Iran. The geographical spread, the number of sites and implied population of the Harappan civilization dwarfs that of contemporary Egypt, China or Mesopotamia.

There is no sign that Harappan cities were laid waste by invaders. Around 2200bce we find that the monsoons had become distinctly weaker and there were prolonged droughts that also affected Egypt and Turkey. However, the Harappans were hit by an even bigger problem—the drying up of the river system on which their civilization was based. Their cities began to disintegrate and they began to migrate, slowly drifting east and south. B.B. Lal puts forward a formidable body of evidence that the Harappan legacy is not just visible in later Indian civilization but is present in everyday life to this day. Take for example, the namaste—the common Indian way to show respect to both people and to the Gods. There are several clay figurines from Harappan sites that show a person with palms held together in namaste. There are even terra-cotta dolls of women with red vermilion on their foreheads. Is this the origin of the “sindur” used by married Hindu women? In short, the Harappans did not just disappear; they live on amongst us. They merged with the wider population and seeded what we now know as the Indian civilization.

It would not be unreasonable to say the Rig Veda was compiled no later than 2000bce, and the geography of the book is very clear. To the east, the book talks of the Ganga river and, to the west, of the Kabul river. It also shows awareness of the Himalayan mountains in the north and the seas to the south (i.e. the Arabian Sea). This is a very well defined geographical area and, interestingly, roughly coincides with the Harappan world. Most interesting of all, the Rig Veda speaks repeatedly of a great river called the Saraswati. The Saraswati is called the mother of all rivers and “great among the great, the most impetuous of rivers,” the “inspirer of hymns.” The problem is that there is no living river in modern India that fits the description. But the controversies over the details of shifting river beds do not change the big picture. In the end it is very difficult to escape the conclusion that the Rig Vedic people and the Harappans were one and the same riparian civilization. My own sense is that the Harappans were a multi-ethnic society, rather like India today. The Rig Vedic people could well have been part of this bubbling mix.

Even after 8,000 years, the lost river Sarasvati was not forgotten. We find its memory echoed in legends, folk tales and place names. At the core of the Rig Vedic landscape was an area called Sapta-Sindhu, Land of the Seven Rivers, a region some feel is constrained to include Haryana, all of Punjab (including Pakistani Punjab) and even parts of adjoining provinces. This is a very large area. But the Vedas clearly mention a wider landscape watered by “thrice-seven” rivers. While one does not have to take it literally as referring to twenty-one rivers, it is obvious to me that the Sapta-Sindhu is a sub-set of the wider Vedic landscape. What was so special about these seven rivers? In my view their importance derives from it being the home of the Bharatas, a tribe that would give Indians the name by which they call themselves.

Architect’s drawing of the upscale 20-acre Vipul Aarohan residential complex: 37 floors, 383 units, each priced at 3.62 crore rupees (US$570,000)

The Bharatas

Although the Rig Veda is concerned mostly with religion, the hymns do mention one event that is almost certainly historical. It was the Bharata king Sudasa’s victory, at great odds, in the “Battle of the Ten Kings” that occurred on the banks of the Ravi river in Punjab. But the real genius of the Bharatas was not their military strategy. It may lie in the fact that the Vedas do not confine themselves to the ideas of the victors but deliberately include those of sages from other tribes, including some of the defeated tribes. Thus, the hymns of the sage Vishwamitra, the great rival of Vashishtha, are given an important place in the compilation. In doing so, the Bharatas created a template of civilizational assimilation and accommodation rather than imposition.

The Bharatas live on today in the name by which Indians have called their country since ancient times: “Bharat Varsha” or the “Land of the Bharatas.” In time it would come to denote the whole subcontinent. Later texts such as the Puranas would define it as “The country that lies north of the seas and south of the snowy mountains is called Bharatam, there dwell the descendants of Bharata.” It remains the official name of India even today.

Sudasa’s achievements may also have triggered an imperial dream that would remain embedded in the Indian consciousness. After his victories, he performed the Ashvamedha or horse sacrifice and was declared a Chakravartin or Universal Monarch. The word chakravarti itself means “wheels that can go anywhere,” implying a monarch whose chariot can roll in any direction. The spokes of the wheel symbolize the various cardinal directions. Over the centuries, the symbolism of the wheel would be applied to both the temporal and the spiritual. We see the symbol used in imperial Mauryan symbols, Buddhist art and in the modern Indian nation’s flag.

The Geography of the Epics

The Gangetic plain was the birthplace of the next cycle of urbanization. From 1300 to 400 bce the area was made up of a network of small kingdoms and republics. Many of them were centered around towns. We come across place names that are still in use, and remarkable socio-cultural continuities. Modern Indian children are still brought up on this era’s legends from the great epics Ramayana and Mahabharata composed in this period. For the first time, we see an awareness of the whole subcontinent as a geographical and civilizational unit. It is also a time that we witness the growing cultural importance of the Asiatic lion, an animal that would come to occupy a central role in Indian symbolism. They tell us a lot about how the geographical conception of India evolved in the Iron Age.

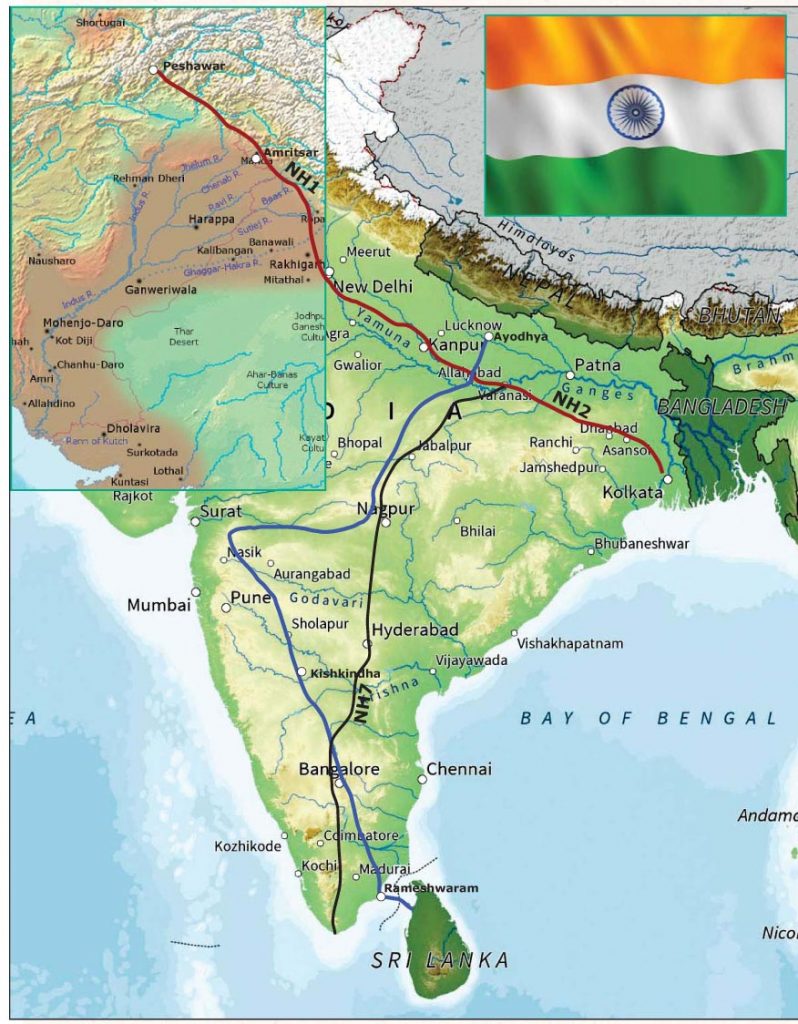

In this book I am not concerned with the historical authenticity of the events described in the epics. My interest is in the expansion of geographical knowledge that we can discern from them. The two epics have very different cardinal orientations from that of the Sapta-Sindhu conception of the landscape. The geography of the Ramayana is oriented along a North-South axis while the Mahabharata is generally oriented on an East-West axis. These are aligned with two major trade routes. The Dakshina Path (or Southern Road) made its way from the Gangetic plains though Central India to the southern tip of the peninsula, while the Uttara Path (or Northern Road) ran from eastern Afghanistan, through Punjab and the Gangetic plains, to the seaports of Bengal.

Symbols of imperial power: One of only 420 protected Asiatic lions remaining in the Gujarat’s Gir Forest National Park.

Ashokan Pillar, Vaishali, Bihar

These two highways have played a very important role in shaping the geographical and political history of India. The Uttara Path was a well-trodden route by the Iron Age and formalized during the Mauryan Empire. It survives today as National Highway 1 between Delhi and Amritsar and National Highway 2 between Delhi and Kolkata, and is part of the Golden Quadrilateral network.

In contrast, the path of the Southern Road has drifted over time, although certain nodes remained important over long periods. The tale of the Ramayana takes us through his [Rama’s] exile in Central India all the way to the southern tip of India and to the abduction of Sita in Sri Lanka. I disagree with those who argue that the epic pre-dates geographical knowledge about South India and that the place names were retrofitted in later times to flow with the story. Take for instance Kishkindha, the kingdom of the monkeys. I visited such a site across the river from the medieval ruins of Vijayanagar at Hampi. The terrain consists of strange rock-outcrops, caves with Neolithic paintings, and bands of monkeys scampering over the boulders.

It is such an evocative landscape that it is likely that Valmiki either visited it or had heard detailed descriptions of it from merchants plying the Dakshina Path or Southern Road. It takes us from the top to the bottom of India and across the “bridge” (possibly just a strip of land still above water then) to the northern tip of Sri Lanka.

Moreover, we can tell a lot about how Iron Age Indians perceived the geographical extent of their civilization from the way Ravana is depicted. He is the villain of the Ramayana but is not presented as a mleccha (barbarian). He is very much an insider: a learned Brahmin and a worshiper of Shiva. Whatever his failings, Ravana and his southern kingdom are categorically within the Indian civilizational milieu. The exchange of goods and ideas along the Southern Road, therefore, had linked the north and the south of India long before political unification under the Mauryans in the third century bc. The name Mahabharata is itself interesting, as it can be read to mean “Greater India.”

The Imperial Dream

In the third and fourth centuries bce, simultaneously across the ancient world we see a new political ideology and ambition. Within a couple of generations, the idea of empire inspired a series of remarkable leaders around the world. Beginning in the sixth century bc with Cyrus the Great of Persia, then in China, 330 bc, King Hui of Qin and around the same time, Alexander the Greek from Macedonia. He tried to take India, made little headway and was later was pushed back by Chanaka and his protege Chandragupta Maurya. Their conquests would redefine the political geography of the world.

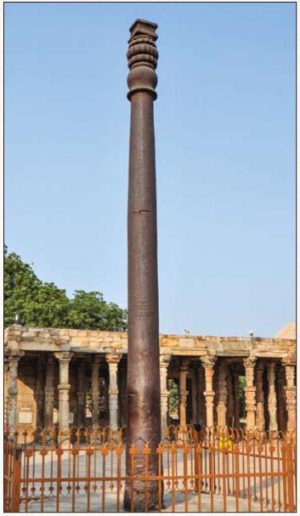

Third in the Mauryan succession, Ashoka is the first Indian monarch who left artifacts of his reign. Best known are a series of edicts engraved on rocks and stone pillars scattered across the empire. These pillars and inscriptions have been found across the subcontinent, from Afghanistan in the north to Karnataka in the south, Gujarat in the west to Bengal in the east. They give us a sense of the scale and extent of the Mauryan empire. Around 40-50 feet high, the stone columns are impressive structures often capped by a lion (or lions), an animal that was associated with the Mauryas since Chandragupta’s time. In some of the pillars, the lions are accompanied with the “chakra” or wheel, which in my view represents the “Chakravartin” or Universal Monarch. They were expressions of imperial power, the Mauryan way of marking territory.

Later rulers understood the symbolic meaning of the Mauryan columns and were always keen to appropriate them. This is why the emperors of the Gupta and Mughal dynasties went out of their way to put their own inscriptions next to those of Ashoka. Therefore, it should not be surprising that when India became independent, Mauryan lions and the chakra became the country’s national symbols. The founding fathers of the Indian Republic intuitively understood that the lions and the wheel stood for the power of the State.

What About the South?

One of the richest sources from this era is the Tamil Sangam literature. Sadly, much of the scholarship around Sangam literature is focused on trying to use the corpus to discern the roots of pristine Dravidian culture, unsullied by “Aryan” influences from the north. This is ridiculous at many levels. The society described in the poems is full of trade and exchange with the rest of India as well as foreign lands. It is a world that is busily absorbing all kinds of influences and clearly revelling in it. Looking for signs of a pristine past misses the point about the people who composed the anthologies. Secondly, the composers of the Sangam poems clearly show strong religious and cultural links with the rest of the country. This includes knowledge of Buddhist, Brahminical and Jain traditions that are of “northern” origin. Even when “local” gods like Murugan (Kartik) are mentioned, they are depicted not as separate but as obviously part of the overall cultural milieu.

India’s national emblem atop Vidhana Soudha, located in Bengaluru, the seat of the state legislature of Karnataka

From 350 bc to the 21st century: The Ashoka pillar capital (top portion), once atop a pillar in Sarnath and now in a museum there.

By the late Iron Age the people in southern India were not just aware of the rest of Indian civilization but were comfortably a part of it. Goods and ideas were flowing along the coast as well as the Dakshina Path. For some odd reason, Indian historians see cultural influences flowing only from the North to the rest of the country. The reality was of back-and-forth exchange. We see this in how the “northern” Sanskrit language evolved over the centuries by absorbing words from other languages. Contrary to popular perception, Sanskrit was never a “pure” language, and its success was largely due to its ability from the earliest times to absorb ideas and words from Tamil, Munda and even Greek. Instead of using it to split hairs over regional differences, I would say that Sangam literature is far more remarkable for the extraordinary continuities it shows that remain alive today.

Today India is witnessing what all developed countries have experienced at some stage of their evolution. Development is ultimately about shifting people from subsistence farming to other activities; urbanization is merely the spatial manifestation of this process. My guesstimate is that urban India will have to absorb some 300-350 million people over the next three decades. This will be one of biggest human events of the twenty-first century. [End of Excerpts]

Colonial Era to Modern Times

Having established the integrity of India as a civilization entity and taken us through to the story of the last great Hindu empire of the Guptas, Land of Seven Rivers continues with the story of Muslim conquerors who carried on their own imperial dream as would-be emperors of the whole subcontinent. We get details of the incredible destruction during their rule, with a focus on the churn of cities, palaces and fortifications. We learn about trade, seafaring and interactions of peoples from Europe to Arabia to China, and the reports of foreign visitors about India’s amazing opulence.

Sanyal then describes the advent of the European powers, most significantly the brutal Portuguese and greedy British. Chapter Six, The Mapping of India, is a mesmerizing story of the top-secret nature of geographical knowledge and how the quest to conquer India was a key factor driving the science of cartography. Chapter Seven, Trigonometry and Steam, describes the incredible fortitude and perseverance of the British men who took six decades to make precision surveys of India by hauling huge theodolites across unknown and dangerous terrain, mapping the subcontinent all the way to Tibet. It goes on to tell the story of the railroads, followed by the first major revolt of 1857, and on to Independence. Chapter 8, the Contours of Modern India, takes us through the tragedy of Partition, the absorption of princely states and the defeat of “the last colonial” when India ejected the Portuguese from Goa.

From an age of urban India 8,000 years ago, Sanyal closes by taking us to modern India’s urbanization, detailing the transformation of villages into slums and into the gleaming towers of Gurgaon. We recommend this book to every Hindu family and to anyone who thought they “hated history” in school but would like to understand India. It reads more like a novel than a documentary. You will come out with a renewed, informed vision of Hinduism’s roots in Bharat Mata, Mother India.

Sanjeev Sanyal is an Indian economist, environmentalist and urban theorist. Currently he is the Principal Economic Adviser in the Ministry of Finance, Government of India. A bestselling writer, he is also the author of three other books. See his Wikipedia article for details, get his books on Amazon, and don’t miss his videos on YouTube.

see: sanjeevsanyal.com