Ten Stories of the Final Moments of Great Sages & Ten Reasons Hindus Do Not Fear Death

INTRODUCTION BY RAMAI SANTHIRAPALA, LONDON; STORIES BY THE EDITORS

There are two indubitable certainties: we were born, and we will die. This is not meant as a morose statement, but as an encouragement to consider the deeper purpose of our existence as an opportunity for spiritual progress. Hindus believe in samsara, the cyclical journey of life, death and rebirth, until such a time that one is freed from this pattern, thus achieving moksha, or spiritual freedom. Knowing this, adepts spend a lifetime preparing for their transition, the mahaprasthana, and effortlessly flow from life to death. Sushila Blackman’s book Graceful Exits is a compendium detailing the grand departures of Hindu, Tibetan and Chinese Buddhist masters. It is that book upon which this Insight is based.

A Medical Perspective: The lenses through which I approach this book are twofold; first and foremost as a practicing Saivite Hindu and secondly as a medical doctor. I am trained in anaesthesia and intensive care medicine. In my field conversations on death and dying are not uncommon. This has left me contemplating the effects of life-support machines and powerful drugs on the mystical transition that is known as death. Recurrently I have found myself having soul-searching end-of-life discussions at a point when a patient is too sick to converse and a family remains unprepared for the loss of a loved one—it felt too little too late. In these highly emotive moments patients and families frequently cling to the chance of life, any chance, as to a piece of driftwood in a stormy sea.

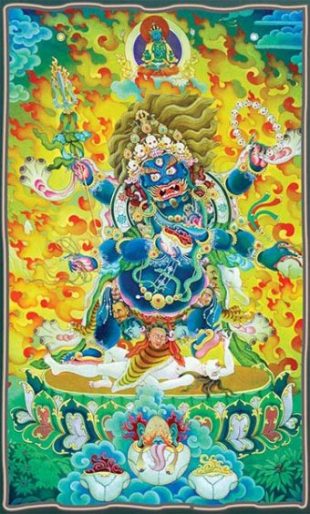

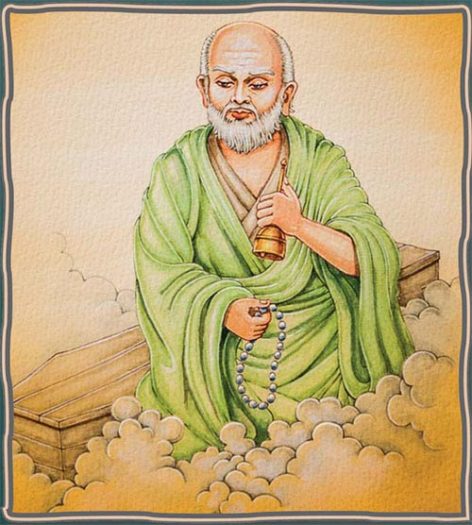

The artist depicts Mahakala (a form of Siva), the Hindu Deity who oversees time and dwells in cremation grounds. He, with Kali, is responsible for the dissolution of the universe at the end of each kalpa.

In many cases there would have been a timely window of opportunity for such conversations when patients could still express their wishes, such as when they consult with a surgeon or anesthesiologist before what is termed “high risk surgery” or with a cancer doctor during counseling for a course of chemotherapy. Even more ideal would be discussing end-of-life wishes as a routine conversation with the family doctor, just as one might review a routine blood pressure check, further demystifying the cultural taboo in the West surrounding the word death.

There is a palpable change in consciousness happening within the medical profession today, with doctors themselves stating, when surveyed about their own end-of-life wishes, that less is more. For example, colleagues and I surveyed anesthesiologists at University College London Hospital. We found that over half were strongly concerned they might be given overly aggressive care at the end of their own life. They value quality of life over quantity.

This changing consciousness of the medical profession, with doctors eschewing heroic interventions in their own last days, is perhaps an example of science and spirituality coming together as the Sat Yuga dawns.

In 2014, leading Harvard surgeon Professor Atul Gawande courageously published a landmark book entitled Being Mortal. Along with BBC’s Reith Lectures, this book turned the spotlight on the increasing medicalization of death, highlighting the disparity between what patients truly value and how they actually die. Home is often cited as the preferred place of death by patients, yet the majority continue to die in healthcare institutions. How beautifully this desire to be at home echoes the wisdom of the East, where the dying are dutifully surrounded by prayerful vigils and the loving attention of close family. The purpose of such preparations is to encourage the soul to exit through the highest chakra, as well as to notify astral-plane helpers of an imminent arrival. So revered is the time of transition that my Guru says to be near a realized soul at the time of samadhi is a blessing that surpasses 1,008 visits at other times.

As I pondered the medical profession’s move from the science of postponing death to the art of dying, Graceful Exits appeared in my inbox as an intriguing window into the spiritual nature of the transition known as death. At the end of the upcoming stories, I will offer a review of Sushila Blackman’s book, which is short in pages but profound in wisdom.

Ten Tales of Transition & Our Artists

In the pages to follow we share the last moments of ten great souls. Their stories can inform our own understandings of death and our ability to be present at the passage of others. As you will see, death to the spiritually awakened is not a fearsome thing. It can be playful or prayerful, but it is always powerful. The ten sages were painted by Pieter Weltevrede of Amsterdam, and the illustrated numbers were created by Ayala Wise who specializes in sacred geometry (TheMandalaWorkshop.com).

DEATH IS UNREAL

The first reason not to fear death is that it does not exist. According to Hindu mysticism, death is a myth, a kind of alternative fact repeated again and again, foisted on us as real, like the fabled unicorn. Death does not exist in the sense most people define it. It’s like the sun coming up in the morning. People say the sun is rising and think of it that way, but the sun doesn’t come up; the earth revolves to reveal the sun. Similarly, death does not end our existence: we just drop off our outer shell and continue our journey in the inner worlds.

If we have not yet achieved moksha, we eventually return to physical birth to resolve our remaining karmas. While most people fear it as a bugaboo, death is actually a miraculous leap in our evolution.

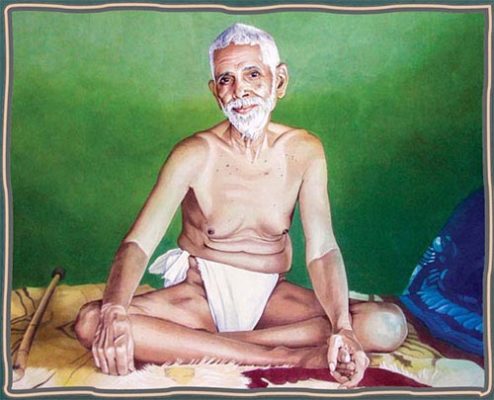

RAMANA MAHARSHI

1879–1950

In 1947, at age 68, Ramana Maharshi was suffering from cancer. When the doctors suggested amputating his left arm above a large tumor, Ramana replied with a smile:“There is no need for alarm. The body is itself a disease. Let it have its natural end. Why mutilate it? A simple dressing on the affected part will do.” Two operations were performed to remove the tumor, but it appeared again, as large as a coconut. Indigenous systems of medicine were tried, and homeopathy, too, but the disease did not yield to treatment. The sage, supremely indifferent to suffering, remained unconcerned. He sat as a spectator watching the disease waste the body; his eyes shone as bright as ever, and his grace flowed toward all beings. Many were coming to say goodbye to the master. In this tradition, it is regarded as a special blessing to be near a realized soul at the time he or she gives up the body. Ramana insisted that the crowds be allowed to have his darshan, and he had his bed placed in a public courtyard. Devotees came and went for weeks as his body slowly diminished. Ramana had compassion for those who grieved, and he sought to comfort them by reminding them of the truth that he was not the body. The Great Departure came on April 14, 1950. That evening the sage gave darshan to all present in the ashram. They sat singing his favorite hymn to Arunachala, the form of Siva as an infinite pillar of light. He asked his attendants to help him sit up. He smiled as a tear trickled down his cheek, and at 8:47pm his breathing stopped. As instructed, devotees prepared a pit in the earth and placed the body there in yogic pose, encasing it in salt. Such interments of great masters are revered as supremely holy. Later a Sivalingam was installed above the crypt and a temple was built around it, thus capturing the sage’s divine consciousness.

REINCARNATION

The second reason not to fear death is that we all reincarnate. Death is not the end of the line. Our scriptures tell us that instead of defining death as an end of ourself, we should realize it is but one phase of the larger reincarnational process.

Many young children and the best of mystics remember their past births, and their remembrances are a reminder that we, too, have lived and died before and will live and die again. The fact of reincarnation can be a great solace for those who look upon death with trepidation. We have many more chances to get it right!

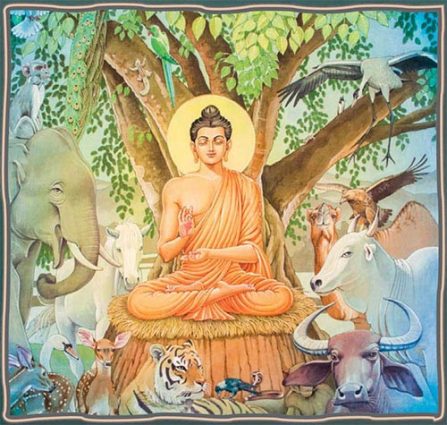

GAUTAMA, THE BUDDHA

CIRCA 563–483 BCE

As he was approaching his own death, Gautama, the Buddha, gathered his monks together and said: “Of all footprints, those of the elephant are supreme; of all meditations, that on death is supreme.” When all had gathered during his final hours, the Buddha gave a sermon.

“It is not appropriate to grieve in an hour of joy.… You all weep, but is there any cause for grief? We should look upon a sage as a person who has escaped from a burning mansion…. It does not matter whether I am here or not; your salvation does not depend upon me, but upon practicing the Dharma, just as a cure depends not upon seeing the doctor, but upon taking his medicine…. My time has come, my work is done…. Everything eventually comes to an end, even if it should last for an eon. I have done what I could for myself and others, and to remain longer would be without purpose.

“Recognize that all that lives is subject to the laws of impermanence, and strive for eternal wisdom. When the light of knowledge dispels ignorance, when the world is seen as without substance, the end of life is seen as peace and as a cure to a disease. Everything that exists is bound to perish. Be therefore mindful of your salvation. The time of my passing has come.”

DEATH IS NATURAL

The third reason not to fear death is that releasing the body is the way of things. All that lives ultimately dies. It is the return of the mortal to the immortal, the time-bound to the infinite source. Some describe it as a river flowing back to its source, the ocean. The water is not destroyed in that merging. That which was two becomes one again. Those who have had near-death experiences report it is not painful. Near-death studies reveal it is a time of elevated consciousness, unity, light and love. It can also be accompanied by great mental lucidity and out-of-body awareness.

Those who have returned from death report they could hear the doctors’ conversations about their heart stopping, could see their family mourning. Much is being revealed by these explorations into the moment of departure.

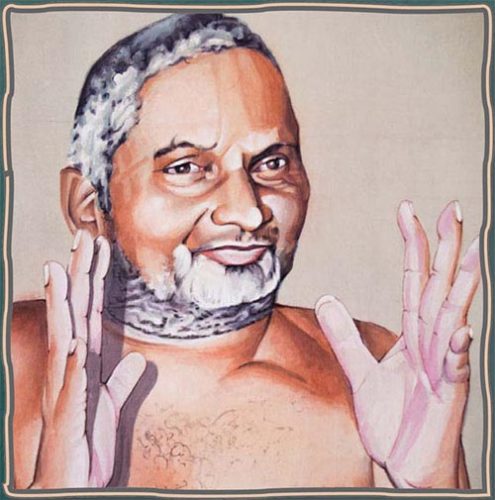

BHAGAVAN NITYANANDA

1897–1961

Three months before Bhagawan Nityananda took mahasamadhi, his disciple Mataji came for darshan. Learning that he had developed a serious ear infection, she began to weep. The master chided,“Why are you crying? Don’t cry. More work is possible in the subtle world than in the gross.” Two months before his departure, Nityananda virtually stopped eating. He just drank water and occasionally ate some fruit. His body, once massive, grew gaunt and feeble. No amount of imploring could persuade him to take food. Doctors were sent for, but he was disinterested in physicians and drugs, not wishing to keep the body any longer. One devotee asked, “Baba, it gives me great pain to see your present condition and weak body. Why can’t you use your divine powers to cure your illness?” The master answered, “This body is mere dust and mud. Spiritual power is not to be used for such things.” About 9:30 on the final morning, Bhagawan directed that coffee be served as prasad to all present. With a smile, he gave a fruit to a young boy, then took two or three very deep breaths. His eyes assumed the shambhavi mudra, turned upward to the third eye. Devotees watched as the sushumna nerve throbbed between his brows. The sound Aum was heard in the room as his life breath merged in the cosmos.

DEATH IS LIBERATION

The fourth reason not to fear death is that it is liberation, a joyous and elevating experience. Hindus call death the Great Departure. For a master, death is not a loss but a release from samsara, for which the Sanskrit word is moksha. Enlightened ones know that the world beyond earthly embodiment is greater, sweeter and more profound.

Neem Karoli Baba, when he saw his departure was near, told his sorrowful disciples, “Today I am being released from Central Jail forever.”

He understood that death is a most exalted state. Isn’t it foolish to fear letting go of the limited physical to be embraced by the infinite Self within?

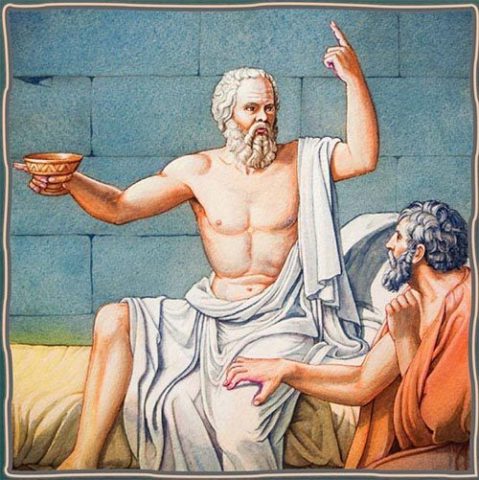

SOCRATES

470-399 BCE

At the age of 71, the Greek philosopher Socrates was accused by the government of Athens of arousing skepticism, inventing new Deities and corrupting the youth of the city. A trial found him guilty, and he was condemned. He was given the choice to be exiled and never teach again, or to accept death by drinking poison hemlock. Socrates boldly rejected exile and opted for death by his own hand. On the fateful day, his distraught disciples gathered around him in the state prison. Even as he reached for the bowl of hemlock prepared by the executioner, Socrates continued to teach, unmoved by his impending demise. After drinking the poison he told those present he was praying for a fortunate transfer from this world to the next. His last words were, “Crito, we owe a rooster to Asclepius. Please, don’t forget to pay the debt” Asclepius was the Greek god of medicine, and a rooster was a normal offering of thanks for recovery from illness. Socrates believed he was cured of the disease of life, and was not frightened by his death. This mundane farewell showed the sage’s detachment from death’s approach. It also points to a common end-of-life practice of mystics, who strive to resolve all karmas, make amends, settle debts, seek and give forgiveness.

DEATH IS A RELEASE FROM SUFFERING

The fifth reason not to fear death is that it removes earthly pains and sufferings. When the soul lets go of the body, the mind is released from debilitating and sometimes unbearable pain.

Transition also marks the promise of a physical and mental upgrade, turning in worn-out equipment for new, fully functioning parts. It is more beginning than end.

TUNG-SHAN

807–869

When Zen master Tung-shan, the founder of the Soto school of Buddhism, felt it was time for him to go, he had his head shaved, took a bath, put on his robes, rang the bell to bid farewell to the community, and sat up till he breathed no more. Thereupon the whole community burst out crying grievously, as little children do at the death of their mother. Suddenly the master opened his eyes and scolded the weeping monks, “We monks are supposed to be detached from all things transitory. In this consists true spiritual life. To live is to work, to die is to rest. What is the use of groaning and moaning?” He then ordered a “stupidity-removing” meal for the whole community. After the meal, he said to them, “Please make no fuss over me! Be calm as befits a family of monks! Generally speaking, when anyone is at the point of going, he has no use for noise and commotion.” He then returned to the abbot’s room where he sat in meditation until he passed away.

DEATH IS EASY

The sixth reason not to fear death is that is a normal human experience, like sleep. People who have been with hundreds of dying people report that something miraculous, even sacred happens in the final hours and moments. The dying surrender to the process; they don’t resist. In fact, they are drawn to their destination with awe and even eagerness. A sign of this can be found in the last six words spoken by Apple founder Steven Jobs: “Oh Wow! Oh Wow! OH Wow!”

Death is a natural experience, not to be feared any more than sleep. It is a quick transition from the physical world to the astral plane, like walking through a door, leaving one room and entering another. Some yogis consider that each night, when we sleep, we experience a micro death.

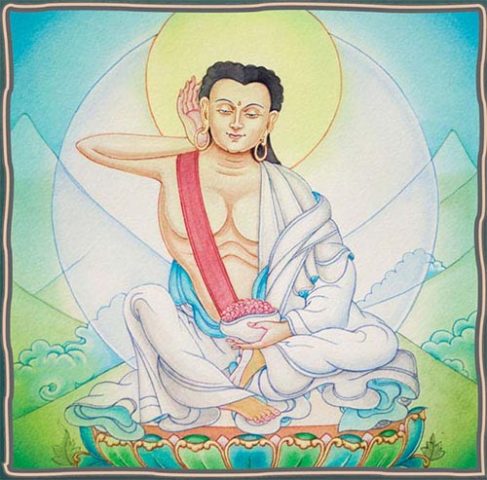

MILAREPA

1052–1135

Milarepa was a renowned yogi of Tibet with vast occult powers. His death was brought about by poison, prepared by an enemy named Tsaphuwa and delivered by the man’s lover. Immediately, as the woman approached, Milarepa cognized her nefarious intent. Realizing his greatness, she fell at his feet, weeping in remorse, and begged him to allow her to consume the deadly food herself. Refusing her offer, Milarepa himself imbibed the poisoned curd, saying, “My life has almost run its course; my work is finished; the time has come for me to go to another world.” His devotees gathered sacred offerings and performed a puja, pleading with their master to invoke his powers to prolong his life with them. But the yogi was firm that he had exhausted his karmas, had made friends of his enemies and with the blessings of his guru was prepared for his next journey. The poison slowly did its work, and days later Milarepa gave his “final testament of precepts.” This last sermon was offered during his cremation, as he sat majestically within the flames in his Indestructible Body, with Gods and devas filling the sky: “In the samsaric ocean of the lokas three, the great culprit is the impermanent physical body, busy in its craving search for food and dress; from worldly works it never finds relief. Renounce, O Rechung, every worldly thing. …O gurus, devas, dakinis: combine these three into a single whole and gain experimental knowledge—this life, the next life, and the life between. Regard them as one, and make thyself accustomed to them as one.”

EVERYBODY DOES IT

The seventh reason not to fear death is that it happens every day to so many. Each day on Earth 155,000 people die. That’s over 6,500 every hour, or 108 every minute. There is no reason to fear what so many experience each day.

Here is an interesting factoid: the Population Reference Bureau estimates that throughout known history 108.2 billion people have lived and died. That’s 15 times as many as are alive on Earth today.

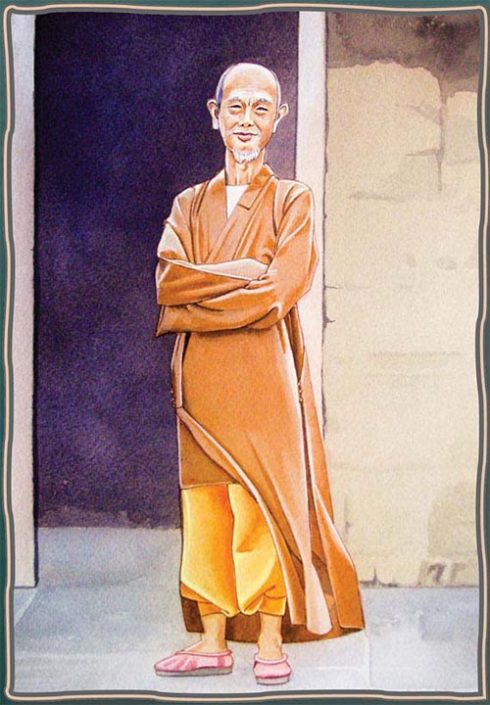

CHIH–HSIEN

CIRCA 830–905

Just before the Chinese Zen master Chih-hsien passed away in 905, he asked his attendants, “Who dies sitting?” They answered, “A monk.” He inquired further, “Who dies standing?” They replied, “Enlightened monks.” He then walked seven steps, with his hands at his sides, and died. Many Buddhist monks regard such a fully conscious death as a sign of spiritual attainment. They prefer to leave the body sitting upright in meditation, or while standing or even walking in the garden—rather than lying down—so as to release the body with full intent and awareness.

NATURE POINTS THE WAY

The eighth reason not to fear death is that methods have been provided. Look at nature, how effortlessly creatures expire. At our monastery when the cats or cows near their end, they simply stop eating, lie down under a tree in the pasture and release the body. In the Jain tradition, santhara is the practice of voluntarily fasting to death by gradually reducing the intake of food and liquids. Not undertaken lightly or unilaterally, it requires a public declaration, community consent and guidance under an ascetic. This manner of exiting the body is viewed in Jainism as the thinning of human passions and the body, and a means of destroying rebirth-influencing karma by withdrawing from all physical and mental activities. This is not considered suicide by Jain scholars because it is not an act of passion, nor does it employ poisons or weapons. A sacred vow is taken before the ritual preparation and practice begins. Though rare in modern times, this formal fasting to death is being rediscovered in India.

There is debate about the practice between the right-to-life and freedom-of-religion viewpoints. The Rajasthan High Court banned the practice in 2015, ruling it suicide. Later that same year, the Supreme Court of India reversed the lower court’s decision and lifted the ban, which made it legal again in India to do a simple thing: stop eating.

P’U-HUA

770–860

When the Chinese monk, wanderer and eccentric Master P’u-hua sensed his end was near, he announced to the people of the nearby town that he would go the next day to the Eastern Gate and die there. Wishing to be at this extraordinary event, the whole community walked in procession behind him and assembled to pay their final respects. P’u-hua then announced: “A funeral today would not be in accord with the mythical Blue Crow. I will pass away tomorrow at the Southern Gate.” The next day most people followed him again, but upon his arrival he decreed, “It would be more auspicious to leave by the Western Gate tomorrow.” On the third day fewer people came, and he decided on the North Gate instead. Some say this was his way of having only the most ardent followers attend his Great Departure and not just the curious. On day four, P’u-hua walked alone outside the city walls and laid himself into the coffin. He asked a traveler who chanced by to nail down the lid. Somehow the news spread, and the people rushed to see him. Upon opening the coffin, they found no body inside, but from high up in the sky they heard the ringing of the master’s hand bell.

SAGES & SCRIPTURE ASSURE US

The ninth reason not to fear death is the assurance of holy ones and our sacred scriptures. Here are a few gems to guide the way:

“Desireless, wise, immortal, self-existent, full of bliss, lacking in nothing is the one who knows the wise, unaging, youthful soul within him. He fears not death!”

Atharva Veda X, 8, 446

“From goodness, understanding is reached. From understanding, the Self is obtained, and he who obtains the Self is freed from the cycle of birth and death.”

Maitreya Upanishad 4.3

Death is like falling asleep, and birth is like waking from that sleep.

Tirukural 339

“A man of discrimination and wisdom is not afraid of death. He knows that death is the gate of life. Death, to him, is no longer a skeleton bearing a sword to cut the thread of life, but rather an angel who has a golden key to unlock for him the door to a far wider, fuller and happier existence. It is necessary for your evolution.”

Swami Sivananda

The Katha Upanishads declares, “There is one part of us which must die; there is another part which never dies. When a man can identify himself with his undying nature, which is one with God, then he overcomes death.”

Swami Paramananda

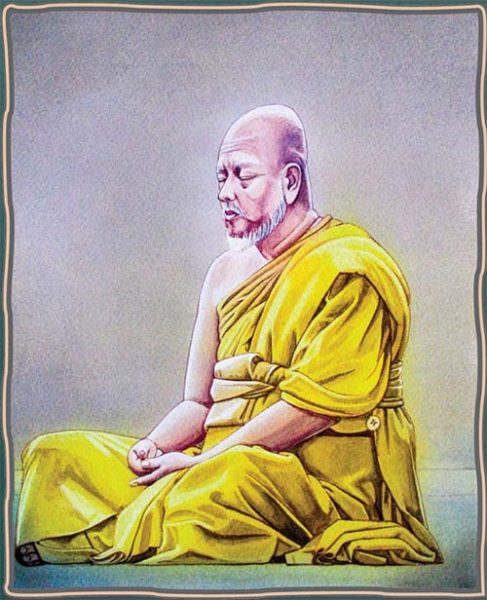

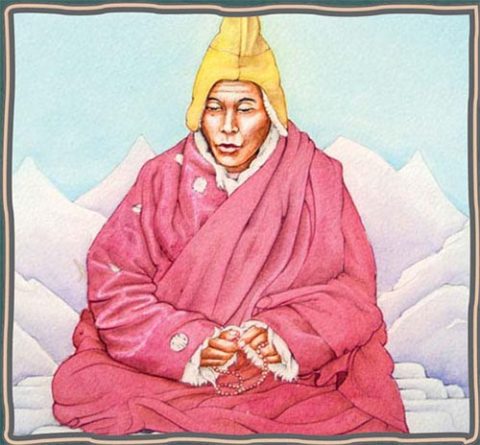

A TIBETAN MONK

DATE UNKNOWN

Certain Tibetan yogis have mastered the winds— the pranas, or inner airs, that flow through the subtle body. One day one such being, a retreat master at a monastery in Kham, asked his attendant: “I am going to die soon. Please look in the calendar for an auspicious date.” Though stunned, the attendant examined the calendar and told the master that all the stars were auspicious on the following Monday. “That is three days away. Well, I think I can make it,” the master replied. A little later, the attendant returned to the room and found the master sitting upright in yogic meditation posture, so still that it seemed he had already passed away. There was no breathing, but a faint pulse was perceptible. The attendant decided not to do anything, but to wait. At noon he heard a deep exhalation, and the master returned to his normal condition, spoke in a joyful mood, and asked for his lunch, which he ate with relish. He had been holding his breath for the whole of the morning session of meditation. The master taught that the human life span is counted as a finite number of breaths, and believing he was near the end of these, he held his breath so that the number would not be reached until the auspicious day. Just after lunch, he took another deep breath, and did not exhale until evening. He did the same the next day, and the next. When Monday came, he asked for confirmation: “Is today the auspicious day?” “Yes,” the attendant replied. “Fine, I shall go today.” Within hours, without illness or difficulty, the master passed away in meditation.

AWARENESS IS IMMORTAL

The tenth reason not to fear death is that you are awareness, and awareness is eternal and deathless. The new science of consciousness is exploring multiverses, non-local awareness and cosmic unity. The old science (still alive and well and in the majority) tells us life begins with protobacteria, evolves to single-celled then multicellular organisms, into fungi, plants, protozoa, insects, worms, reptiles, and mammals, such as Homo sapiens. With advanced animals and humans came the cerebral cortex, which they say creates consciousness.

Old-school scientists don’t know what consciousness is, but they are certain that it is an epiphenomenon of matter, and when the brain dies, consciousness ceases to exist! The new science retorts, “No, no, no. The brain does not create consciousness. Consciousness creates the brain, and continues after brain death.” Evidence of the nonmaterial existence of consciousness is drawn from near-death experiences, out-of-the-body experiences, non-local awareness, reincarnational experiences and the wild world of quantum physics. Consciousness studies confirm what Hindu mystics have been saying for millennia: you are the All and Everything.

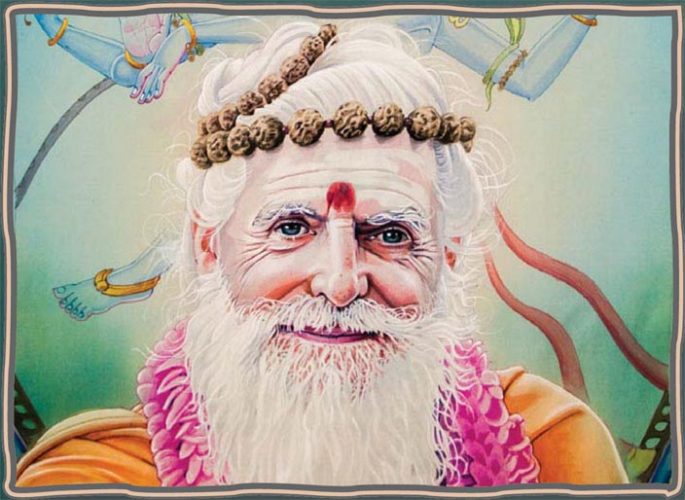

SUBRAMUNIYASWAMI

1927–2001

On October 6, 2001, doctors in Hawaii discovered Gurudeva had advanced metastasized cancers in his colon, small intestine and brain. Three teams of specialists confirmed that he had not long to live. Ten days later he informed his senior monks that he had decided to fast to death. He had taught of this traditional way of leaving a terminally ill body, called prayopavesha, and now he would himself follow that difficult regimen, preferring the conscious departure of the yogi to weeks or months of medical intervention and systemic deterioration leading to loss of consciousness. Gurudeva asked how long this would take. After hearing about others who had fasted in this manner, he said, “So, in about 24 days it will be over and I will be with you 24 hours a day, not just during sixteen waking hours.” In the ensuing weeks, his own departure was not the most onerous work. It was assuaging the sorrow in the hearts of his monks. He offered encouragement and solace, at one point whispering, “Everything that is happening is good. Everything that is happening is meant to be.” His goal now was to resolve all karmas and depart through the crown chakra. One evening the monks gathering around his bed took turns reading from his seminal talk, The Self God. In the dim light, the room bristled with shakti. Breaking the silence, Gurudeva commented, “So, the Self God was true in the 1950s and it is still true in the 2000s.” All laughed in acknowledgment that the Absolute Truth is always the same, always true, transcending life and death. There is a form of breathing, called Cheyne-Stokes, that the dying experience for a few hours. A deep breath is taken and held for up to a minute, when another such breath comes. When Gurudeva did this for ten days, his doctor said, “That’s astonishing. It can only be attributed to his lifetime of meditation.” At one point, in the dark of night, Gurudeva told the monks that Yogaswami, his own guru, had come to him. He then said, “Everything is finished. All is complete.”

4 Takeaways

ON THE TRANSITION CALLED DEATH

1. As Natural as Possible

Sages hold a natural death in high regard, and choose to pass without mind-numbing drugs and high-tech machines, at home if possible, surrounded by those we love. Avoid heroic medical measures that diminish the quality of life, remembering Abraham Lincoln’s adage: “It’s bit about the days in your life, but the life in your days.”. Cremation of the body is a natural choice for Hindus

2. Don’t Mourn Excessively

Those who leave the earth plane often remain aware of those who remain. Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami described how the emotional traumas and attachments of those still living can affect the departed soul, who is naturally saddened to see loved ones suffering. Knowing this, it is good to mourn, but not over much.

3. Elevate the Mind

The moment of death is crucial. Where we are in consciousness at that final moment sets the direction of our onward journey. If we are in fear, or lodged in any of the other lower chakras, we will end up on the lower astral plane, a realm of misery and suffering, until our next birth. But if we are in the world of love and light, we will soar into the higher superconscious realms.

4. Turn to Spiritual Master

When most people think of dying, they tend to be more concerned with avoiding pain and suffering than with confronting the meaning of death and how to approach it. We need good role models to place death in its proper perspective and show us how to leave this world gracefully. For this, we can turn to the spiritual masters of all faiths. Hindu gurus will remind us we are not our body, mind or emotions. We are pure consciousness-an immortal spirit that never dies.

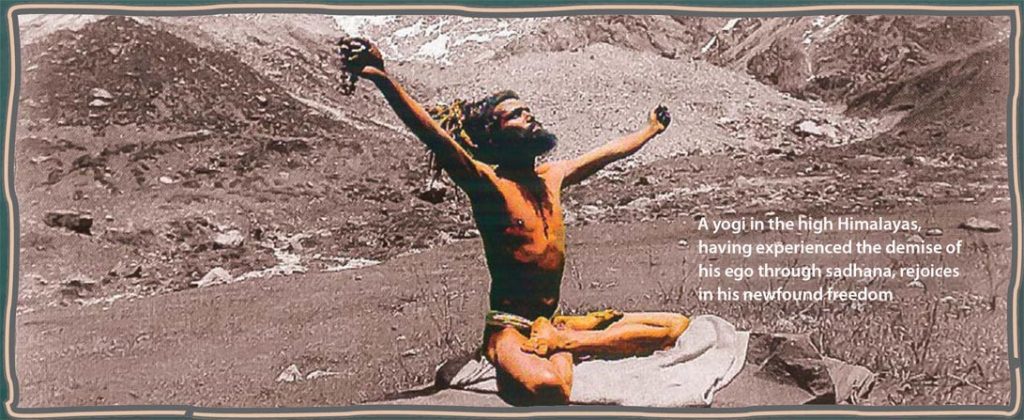

“Die Before You Die”

You must die before you die.” In this enigmatic axiom, Sage Yogaswami expounds one of the rarely discussed goals of the spiritual path—to experience the death of ego before physical death. Great souls regard the death of the ego as an affirmation of life, not a disgust with or denial of life. Their understanding of death and willingness to face it consciously informs their existence, making life more precious, more known.

To die before you die is to discover your spiritual Self before you release your physical body. The ego does not let go willingly; thus this is not a practice for the timid who cannot look into the face of their own foibles and flaws. It is more the work of resolute contemplatives than career-beguiled achievers, of the rare ones who seek to diminish desires and repeal preferences. The term death in the Hindu perspective is really a synonym for transcendence. When the ego dies, one enters into a greater understanding of Self. Similarly, when the body dies, one enters a vaster identity. Ironically, dying in this way is perhaps the most alive one will ever be.

“Just as a lamp gets extinguished when the oil is exhausted, so the yogi extinguishes his former self when ego identification ceases to exist in perfect meditation.”

Sarvajnanottara Agama, Yoga Pada, verse 51

This theme is voiced in the Katha Upanishad (2.3.13): “There are two selves, the separate ego and the indivisible atman. When one rises above ‘I, me and mine,’ the atman is revealed as one’s real Self.” Eventually, we are all forced to let go of the material world through the natural and ineluctable process of death. It is a profound teaching of the Eastern faiths that ardent, mature spiritual aspirants can achieve this level of perfect detachment while still living.

How is this done? A conscious ego death can be initiated through revelatory meditation, raja yoga, other forms of intense sadhana or divine grace. By balancing our karmas, by finding perfect stillness, by severing all bonds and felling all false identifications, we are thrust beyond the realm of change into the changeless. The holy texts advise that such an advanced discipline be undertaken with the guidance of a guru who knows well both the person and the process.

Even if the ultimate obliteration of separateness is not achieved, there are practical benefits to the effort. It humbles us and keeps our words and actions in alignment with our higher intentions. It removes conflict, confusion and separateness from our existence. Milarepa, a Tibetan yogi of the 9th century, explained, “Life is short and the time of death is uncertain; so apply yourself to meditation.” Those who die before they die learn that there is no death. For them, the transition called death, when it comes, is not disquieting. For them, death is not a frightening foe but a familiar friend. When death is seen as transformation into something greater, it can be fearlessly looked forward to with curiosity, and even joy. As J. K. Rowling put it, “To the well-organized mind, death is but the next great adventure.” In the words of Rumi, “Our death is our wedding with eternity.”