India Foundation’s Center for Public Diplomacy and Soft Power collaborates with Ritambhara Ashram to promote International Yoga Day

BY SUDARSHAN RAMABADRAN, CHENNAI

Soft power is subtle. unlike hard power, it works by changing people’s interests and preferences, thus wielding its influence from within. While the term soft power has its genesis in the West, India’s soft power has influenced the world from time immemorial. Michel Danino’s book, The Lost River: On the Trail of the Sarasvati , describes Mohenjo Daro (in today’s Pakistan)—believed to be the world’s largest city of its time—as actively engaged with other countries, from Europe to Mesopotamia to China. Swami Vivekananda’s famous speech at the World Parliament of Religions in 1893, along with his subsequent teaching mission in the West, popularized yoga and meditation in the West. The great religions of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism, now widespread, are all Indian exports.

Five years ago, India put yoga on the global map by inspiring the United Nations and countries worldwide to declare June 21, the summer solstice, as International Yoga Day for the benefit of humanity. The adoption of this resolution with a record 175 co-sponsors marked a widely acknowledged chapter in India’s soft power story. The day gave a boost to yoga in every nook and corner of the world.

Yoga’s influence is unmatched, organic and pervasive. Eddie Stern’s book One Simple Thing: A New Look at the Science of Yoga, expounds upon the rich ancient contribution of yoga. Stern, a New York-based ashtanga yoga teacher and author, credits T. Krishnamacharya and his disciples as being responsible for at least half of the yoga that is practiced around the entire world today. He cites a 2016 study sponsored by Yoga Journal that concluded around 36 million people in America were practicing some form of yoga. Another source estimates this has increased to 55 million in 2020 in America and possibly 200 million worldwide, mostly Indians.

Yoga, as practice or philosophy, could mean many things to each one of us. The word itself means to join, from the Sanskrit root yuj. By turning the attention within, yoga enables a process of self-discovery, of joining with one’s true self.

As a student, seeker and practitioner of yoga, I have tried to ask myself for the sake of clarity some basic questions in order to delve deeper. What exactly are the sources of yoga? What form of yoga is practiced in today’s time and age? Is it more of physical asana and pranayama practice? Or is it more reflective, moving to the antaranga, inner work aspect of yoga, making it a more transformative practice? Finally, I often muse, what could possibly be the future of yoga?

Roots of Yoga

Disturbingly, the increasing commercialization in recent years is leading to yoga’s being cut off from its roots. Yoga has become commoditized. The Yoga Journal study estimated in 2016 Americans alone were spending us$16 billion a year on “yoga classes, clothing, equipment and accessories,” and that spending worldwide was likely $80 billion. In addition, curious variations have been invented. “Beer Yoga” is held in a barroom, drinking beer during or after the asanas. In “Goat Yoga” tame goats engage with the practitioners. Then there’s “Laughing Yoga,” “Hot Yoga,” “Naked Yoga” and more.

Raghu Ananthanarayanan, an alumnus of IIT Madras, student of Krishnamacharya and co-founder of Ritambhara Ashram based in Tamil Nadu, explains that the roots of yoga are eternal, nourished by the insights of the rishis. “As with anything that becomes popular,” he told me, “unscrupulous teachers focusing only on the commercial aspects have come in and muddied the waters. Cultural appropriation, also, has impacted the purity of the stream.”

The commercialization and cultural appropriation of yoga is most clearly discernible in the US, as evidenced by scores of articles and research papers. Working to stem this tide are educational and advocacy organizations such as the Hindu American Foundation, steering important efforts. For example, HAF’s “Take Back Yoga” campaign highlights the importance of the real roots of yoga. Suhag Shukla, HAF’s executive director, explains, “In the West, in the yoga industry and in academia, we see a deliberate delinking of yoga from its religious and spiritual Hindu roots to achieve the successful commoditization and marketing of yoga.” She adds that specific research efforts are attempting to delink the asana practice from the tradition of yoga itself.

These disturbing trends have even led to conflicts with nature, which violates the very purpose of yoga. Hariprasad Varma, yoga coach and member of the Ritambhara Ashram, points out, “For instance, the microfibers used in New Age yoga pants [and many other garments] are reported to be among the major sources of plastic that is polluting the oceans and contaminating seafood. It is disheartening to see many popular yogis promoting such yoga pants as fast fashion. If one were rooted in yama-niyamas of yoga, one would develop sensitivity to the world and beings around.”

But all is not lost. Campaigns such as “Take Back Yoga” and related efforts are shaping global conversations on the five Ws (What, When, Why, Where, Who) and the one H (How) of yoga. “The high point was sparking off a global conversation,” explains Suhag. “I measure its success by the fact that it got coverage in mainstream media including the Washington Post, New York Times, CNN, National Public Radio , and unexpected platforms, including Al Jazeera . To this end, the coverage provided an opportunity to reach a diversity of audiences and get them to think more deeply about what yoga is and where it came from.”

In addition to global conversations steered by advocacy organizations such as HAF, credible teachers both inside and outside India are working to preserve and honor the sacred roots of yoga and stay true to its tradition. For these teachers and their organizations, yoga is too deep a philosophy to be cut off from its roots. “The roots of yoga lie in Vedic wisdom,” declares Raghu of Ritambhara Ashram. “This is undeniable. However, I believe that yoga is deep and wide, and these disturbing developments will not blind the real seeker.” He advises that one must be alert and never let one’s guard down in these matters.

New York’s Eddie Stern observes that the practice of mindfulness followed today by many across the world has its origins in Buddhism, and practitioners and teachers of mindfulness rightfully ascribe it so. In a similar vein, he says, it is important that we ascribe yoga to its real origin, which is India and Hinduism, and this is especially the responsibility of Westerners taking to yoga. Anyone and everyone can practice yoga, he says, but they should recognize and acknowledge its source in India’s traditional ethos. “It doesn’t mean that you have to be a Hindu to practice yoga, just as you don’t have to be Buddhist to practice mindfulness. But what we should be doing as Westerners practicing a Hindu practice is to ensure that they correctly understand the practice originated in India.”

Adding Inner Yoga to Our Outer Yoga

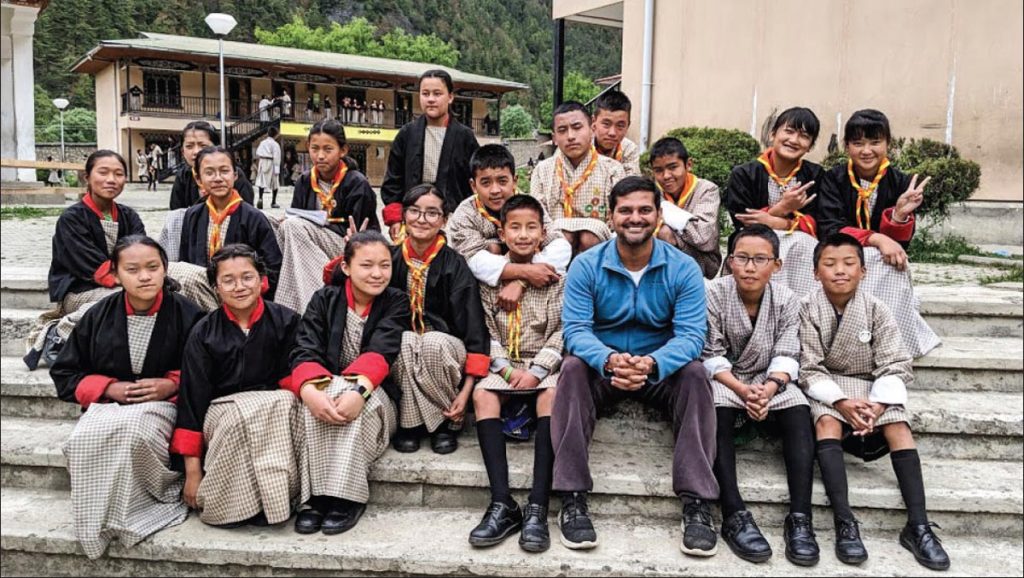

Yoga is one of twenty soft power themes focused on by the India Foundation’s Center for Public Diplomacy and Soft Power. In promotion of this theme, and in the run-up to this year’s International Yoga Day, the Center collaborated with Ritambhara Ashram to create a unique yoga initiative, which has now run for two years and spans 17 countries.

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra presents eight “limbs” of yoga: yama (ethical restraints), niyama (observances), asana (postures), pranayama (breathing), pratyahara (withdrawal), dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation) and samadhi (absorption). The first four comprise bahiranga , the yoga of the outer limbs. The second four comprise antaranga , the yoga of transcendental inner space.

Moving from the outer yoga to the inner is a challenging process that requires turning away from the power of the external world and shaping one’s mind so that it becomes capable of entering the realms of samadhi. During research for this article, I learned that 70 of the 195 sutras in Patanjali’s classic, Yoga Sutras , speak of this very important component, antaranga yoga.

What does antaranga yoga, also known as “Inner Work Through Yoga,” help achieve? People come to yoga not just for physical practice. Being a student of yoga, I do attach immense value to the physical practice. But the inner search enabled by contemplation to attain knowledge of oneself is the pristine goal of one taking to yoga seriously. Swami Vivekananda states in the Complete Book of Yoga that the goal of mankind is knowledge. This, he believes, is the one important ideal placed before us by the Eastern philosophy.

Making it Real

For us at the India Foundation’s Center for Public Diplomacy and Soft Power, Ritambhara Ashram does all the heavy lifting in organizing and presenting this process of yoga. Hariprasad, who takes the lead, guided by Raghu, keeps the trainers and teachers from various schools involved. Hariprasad has alluded to the importance of seamlessly combining both facets of yoga. “When we thought about the program design for the International Yoga Day with the India Foundation’s Center for Public Diplomacy and Soft Power, we decided it was important to highlight both the bahiranga and antaranga aspects of yoga. We used curated stories from Mahabharata for facilitating the antaranga yoga sessions. In these sessions, the evocations and provocations of the individual as they engaged with the characters and incidents in the story were used for deeper contemplative dialogues, connecting them to concepts from Yoga Sutras where relevant.”

The feedback from trainers and teachers from several countries indicates success. We have found the need to include this very integral component of antaranga yoga, to be an effective catalyst in pursuit of inner peace for an individual facilitating real change. For the first year, in 2019, we called the program “Yoga for Peace.” This year we have remodeled it with the name “Peace and Sustainability Through Yoga,” to be more relevant in the Covid-19 era.

Yoga teachers and practitioners from several countries participated in both years’ initiatives. For both the bahiranga and antaranga practices we have had participants from India, France, Greece, Italy, Germany, Turkey, Pakistan, United Kingdom, USA, Canada, China, Bhutan, Brazil and the UAE. In addition to this, we have had trainers and teachers from Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Vietnam who have taken up just the bahiranga aspect but yet been involved with the overall initiative. This consolidated team is effectively steering the yoga soft power theme, or in today’s marketing terms, a vertical , meaning an area of interest to a specific group of people.

Any form of yoga practice is for inner transformation. It has to do with the mind. If, as a seeker, you find there are impediments and you are in pursuit of decluttering the mind, yoga is a great manual to use. Its deeper significance can be understood if one can move from the physical to exploring the inner work, or at least finding the right balance between the two. In doing so, the real essence of yoga will reveal itself to the seeker. I say this with conviction, as it has made an impact on most of the practitioners throughout the world whom I have spoken to, in and through our evolving effort.

Feedback from Countries

Antaranga yoga is not to be seen as something different from yoga. As soon as the mind is still with the help of the regular bahiranga practices of asana and pranayama, antaranga begins. This time of introspection proves invaluable for self-unfoldment. This is precisely what we have read in the feedback received from yoga teachers and trainers from across the world.

Valentina Bianca Ranzi, a yoga teacher from Milan in Italy and an active member of our cohort, feels that yoga in Italy is still a body-oriented exercise. But she took to learning, studying and teaching it, as she was in pursuit of understanding the deeper essence of life. The ability to introspect and reflect after the regular asana-pranayama practice has enabled her inner search and become a tool to settling down reactions to the pair of opposites that we face in life—reactions that create a ruckus in everyone’s body-mind complex.

Ayça Erdem, a yoga teacher from Turkey, has learned to analyze the mind more deeply by adding antaranga practice. She says she can see its effects in her mind and in all aspects of her being, including body, breath, perceptions and actions.

Ajlaan Raza Sayani, a yoga enthusiast from Pakistan, reports the yoga movement is nascent and small in his country, but has grown noticeably in the last three years. In and through the antaranga yoga practice, he has learned not to judge any stimulus that comes his way, but to simply be aware. In order to be aware, he affirms the key is understanding that you are not your thoughts. He’s discovered that thoughts are temporary and go as speedily as they come.

Consistent and successful practice of antaranga yoga will help connect minds and enable one to understand oneself better, for this is the very objective of yoga. It would be a great disservice to the tradition if we do not inspire the students and teachers of yoga to pursue yoga’s supreme goal of spiritual understanding.

The Future of Yoga

Considering the slow but definite shift to understanding the depths of yoga through antaranga yoga, it is vital to see where the future of the yoga movement is headed. What should we expect to see, say, in 2030?

I see two prominent strands emerging, but these, too, may evolve with time. The unanimous response we got from credible yoga teachers in India and abroad indicate how important it is for seekers to put into practice antaranga yoga and create the intended balance, if not already achieved. This will decisively instill in seekers the clarity they seek while practicing yoga. It will relieve the sufferings that the seeker is experiencing as well, for which he or she took to practicing yoga in the first place.

Secondly and most importantly, I feel that yoga will promote social cohesion. It will be the responsibility of yoga teachers to include people from various sections of society, regardless of their caste, creed or color, in imparting the lessons of yoga. This will truly achieve the holistic vision of “Yoga for All and All for Yoga,” as well as succeed in keeping the authentic traditions and practices of yoga intact.

Analysts have stated how difficult it is for observers to measure a country’s soft power prowess, but over the years we have been able to see the subtle effectiveness of the nature of yoga. It has effectively contemporized the famous saying of the Tamil philosopher, Kanniyan Pungrundunar, Yaadhum ore, yaavarum kelir , which means “Every town is my town and everyone is my relative.”

The author is Senior Research Fellow and Administrative Head at India Foundation’s Center for Public Diplomacy and Soft Power