By RAJIV MALIK, NEW DELHI

Think like a genius. Work like a giant. Live like a saint.” This cogent affirmation of Swami Omkarananda Saraswati resonated throughout my stay at Omkarananda Ashram Himalayas, his Indian headquarters adjacent to the Sivananda Ashram in sadhu-laden Rishikesh. Swami began the Ashram 30 years ago on the bank of the river Ganga to facilitate realization of God in daily life and to render selfless service to the local hill people. I met the Ashram’s team of migrated Europeans–led by Swami Vishveshwarananda Saraswati–who manage the educational and cultural institutions in the Tehri Garhwal region surrounding Rishikesh.

In 1947 at the tender age of 17, Swami Omkarananda was initiated into sannyas by the late Swami Sivananda. He promulgates the teachings of Adi Shankaracharya, founder of the Smarta sect of Hinduism, and personally worships Goddess Shakti. Thirty-two years ago on divine orders, Swami Omkarananda left India to teach eager seekers of Truth in Europe. Now permanently residing in Austria, he has brought hundreds of Europeans formally into Hinduism through the namakarana samskara. Over 170 of them have been initiated by Omkarananda as renunciate monastics–sannyasins and sannyasinis. One of his earliest initiates is Swami Vishveshwarananda who, from 1967 to 1982, trained closely with him in Europe.

“I was a good pilot and loved flying,” Vishveshwarananda told me. “I met Swami Omkarananda in 1965 and was mesmerized, led from darkness to light.” At one stage he asked Swami whether to continue flying. Swami said he should choose between spirituality and flying. So he quit flying. It was a surprise to his co-pilots, but he never looked back. “Switzerland is full of material comforts. I chose to renounce this and came to the path of spirituality. I was surely a Hindu in my previous birth.”

In 1982 Vishveshwarananda was sent to India to serve as vice-president of Omkarananda Ashram Himalayas, and is now Omkarananda’s designated spiritual successor. They communicate daily, and while Omkarananda has not visited India for 32 years, the Ashram runs so well it is as if he is personally present.

Vishveshwarananda is assisted by a core team of monastics: Swami Satchidananda, Swamini Gaurishankarananda, Swami Vishvarupananda and Somashekhari, all from Europe. Laudably, they have become official citizens of India to amalgamate with the local community. “Jealous people spread misinformation that we were foreign agents of Christian missionaries,” laments Swami Vishveshwarananda. “This is rubbish. But unfortunately I cannot change skin color. We hold Indian passports now and are Hindus because of our past karmas.” Departing from tradition, the Ashram houses men and women, but Vishveshwarananda affirms that “Women are viewed as divine mothers. Purity is maintained.”

Sri Narasimhulu, senior manager of the nearby Sivananda Ashram, appreciates the Europeans’ dedication. “Most monastics here are Swiss and German. They take temple management seriously. Their love for their guru is rare. They have been asked to serve in Rishikesh as it is a poor area. They have taken the guru’s order seriously. If he asks them to jump in Ganga, they will do so. That is the level of devotion.”

There are also eager young monastics settling in. Three Swiss and German youth, who grew up in Swami Omkarananda’s Austrian ashram, recently visited India on holiday. Enamored with spiritually-charged Rishikesh valley, they sought and received blessings to settle there for good. In Europe they had attended top academies to perfect technical, including computer, skills. Upon their request in 1992, they were initiated by Swami Omkarananda. Two girls, ages 22 and 18, are now known as Swamini Virajananda and Swamini Tripurambikananda, and one boy, age 13, is Swami Vidyabhaskarananda. All three are now plunging into sadhana, Sanskrit, scriptures, astrology, academic studies, temple worship and, of course, the cold river Ganga for holy dips.

Rishikesh is known for being slow and relaxed, but activity in Omkarananda Ashram cruises at breakneck speed by comparison. The day begins at 4am and ends late. The Ashram residents I met–Indians and Indian citizens of European origin–live a disciplined life, balancing sadhana (spiritual discipline) and service. There are fixed timings for pujas, meditation classes, bhajans and yagnas. Mathavasis fulfill Swami Omkarananda’s central teaching: “Practice the yoga of synthesis. Be a karma yogi, bhakti yogi, raja yogi, mantra yogi, jnana yogi. Love the all-pervading, all-knowing God with all your heart and soul. Experience Him here and now, and distribute the fruits of that Experience to all mankind.”

To efficiently distribute those “fruits,” high-tech is the norm. Unlike other ashrams with their spartan facilities, Omkarananda’s is outfitted with cordless phones, new computers, fax machines, a compact offset press and a website (omkarananda-ashram.org). Rishikesh has daily power cuts, but that’s no cause to interrupt the Ashram–thanks to a huge generator which assures the constancy they need for so many projects. Forgetting God any time is disallowed, so a stereo system plays “Hari Nam” chanting all day.

Eight cows–inspired by the tunes of bhajans–produce more milk than the Ashram requires, so extra milk is sent to other ashrams. Monkeys and snakes regularly visit and are offered food. They are not harmed, and therefore do not harm the residents. A public library, homeopathic center, guest house and Patanjali Yoga Center on the banks of the Ganga serve community needs. At the Yoga Centre, Ma Usha Devi, a Swiss devotee, teaches hatha yoga and meditation daily.

Smaller Omkarananda ashrams are located in nearby Munikireti and Lakshman Jhula. They are referred to as temples because of their daily pujas and havanas. Visitors can meditate, study scriptures or perform karma yoga. The Ram Mandir in particular allows nature lovers to grow trees, fruits and vegetables.

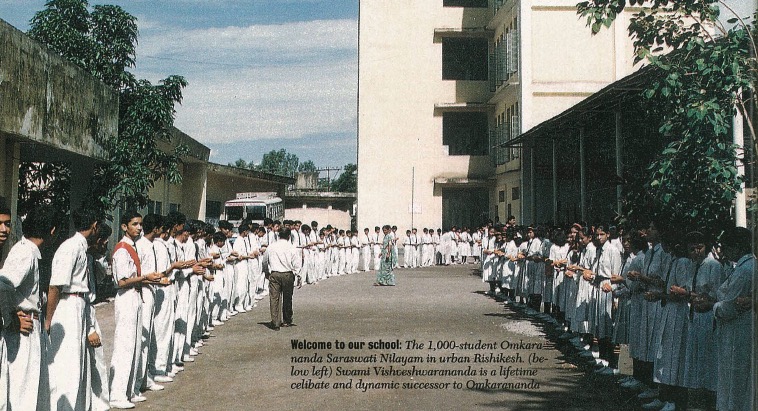

Education: Now we come to Omkarananda Ashram’s most crucial community service–academic and cultural education. Twenty-six schools, including two dance and music academies, are overseen in urban Rishikesh and the distant hill areas–some so rural they can only be reached on foot or horseback. Most hill people live in abject poverty, and their childrens’ only source of education is through the Omkarananda Educational Society. I was warmly received at Omkarananda Saraswati Nilayam, a large city school with 1,000 pupils. Priyanka Rajwar, a 15-year-old student here, told me with joy, “We have excellent rapport between teachers and students, with freedom and understanding. At home I have a temple and I meditate on God–the Superpower.” Most students are Hindu and the principal, Mr. R. D. Pawar, explains how they learn Hinduism through a “moral science” class. “We teach from the Panchatantra, Hindu scriptures and Puranas, and recite Hindu prayers, including Ganesh Stuti. But there is lack of proper books through which we can teach Hinduism in plain English.”

Remote hill schools are located in picturesque settings, far from city life. Many are in economically backward villages, hence more affordable fees are asked–just 25-50 rupees per month. These schools are franchised by local social workers and businessmen, but most are not self-sufficient economically and depend totally on subsidies from the main ashram. One teacher complained about a lack of basic teaching materials, low salary and poor working conditions. But Swami Vishvarupananda reminds, “The schools are regularly inspected and funds provided according to needs. Still, with so many schools it may of course happen that some teachers are not satisfied. Whatever comes to our notice is certainly looked into and given proper attention.” Despite any shortcomings, parents are happy and feel Omkarananda schools are better run than government schools, with more emphasis on moral education.

My stay at the Omkarananda Ashram was joyous. The worshipful sadhanas performed by the monastics and contribution of the ashram in serving the hill people, should be emulated by other religious institutions. Swami Omkarananda has even offered Hinduism Today a large building near the Ashram for operating in India. A big boost will be given to the Omkarananda institutions if Swami decides to revisit Rishikesh. His many adorers here are longing that the great soul who took Hinduism to Europe 32 years ago will one day visit. Swami says he is “still awaiting orders from the Divine Mother.”

EUROPEAN HOME BASE

CONVERTS PRACTICE HINDUISM IN CHRISTIAN HEARTLAND

Having enjoyed a thousand years of peace, Switzerland is the world’s oldest democracy. This land of stunning landscapes and United Nations conferences is also home to Swami Omkarananda Saraswati’s primary ashram, founded in 1965. The ashram rapidly spread wings to Germany, Austria, England and France. Swami himself lives 50 miles away, at his small ashram in Austria, which he has not left for 12 years.

Over a 30-year period, an impressive 170 Europeans have relinquished family life to take sannyasa diksha in Omkarananda’s monastic order. You won’t find anything in their lives but pure worship of God as the Divine Mother, and supreme dedication to their guru.

Daily pujas (ritual invoking of the Gods) and Rudra abhishekas (bathing the Deity image) form the substratum of ashram life. For the “peace, progress and prosperity of all mankind,” a 24-hours-a-day Akhanda-Sarva-Devata havana (fire ceremony) lights the Ashram’s temple-like central rooms, maintained since 1974. Monastics take turns tending the havana and offering prayers through the fire. Without a break their vigil has continued for roughly 201,480 hours–an extraordinary feat of spiritual continuity matched by few ashrams.

Three decades of Omkarananda’s discourses are recorded on magnetic tape and comprise tens of thousands of typed pages. These pearls of wisdom reach seekers through the Ashram’s two magazines.

Monastics cultivate skills in the ashram’s secretariat, press and publication department, video, audio, computer sections, administration, maintenance and renovation of properties, and on new sites in the Austrian Forest Ashram. In the Ashram’s Sanskrit and Vedanta Academy and Library, higher philosophical studies are pursued.