By JULIE RAJAN, PHILADELPHIA

Last time you visited a doctor, you probably gave little consideration to the impact of René Descartes upon your impending diagnosis and treatment. But maybe you should have, for this 16th-century French philosopher–famous for saying, “I think, therefore I am”–postulated that the human body is just like a machine. This, in turn, led to the development of the kind of medicine–likely practiced by your doctor–which treats disease as one would fix a machine, mechanically, with minimal regard for the person as a whole.

Slowly, reluctantly, this so-called “modern medicine,” which has dominated for hundreds of years, is changing. Its mechanical approach of drugs and surgery has many advantages, especially with regard to infectious disease and structural damage, but also many limitations. It tends to ignore the patient’s lifestyle, minimize his mental state and dismiss his spiritual needs–and as a result misses relatively simple forms of prevention and effective treatment for conditions unsolvable by either drugs or surgery.

A great change is in the wind, led not by doctors, but by patients disillusioned with the unfulfilled promises of more drugs and more surgery, unable to pay their ever-increasing medical bills, unaccepting that they are “just like a machine” and unwilling to be treated like one. Traditional Hindu medicine–ayurveda–is yet a small part of this change, but the Eastern philosophy of the connection and interrelatedness of body, mind and soul is very central. The trend is so strong that the US government is devoting us$12 million a year to fund a new department, the Office of Alternative Medicine, to study and promote it. In 1996 OAM director Dr. Wayne B. Jonas stated, “One out of every three Americans saw an alternative health-care practitioner in 1990.”

Just what to call this many-faceted revolution against the mechanistic approach is unclear. Western medicine is often called allopathy, though this is not a precisely accurate term. All other approaches are called “alternative medicine,” “holistic medicine” or “traditional medicine,” even though many such methods are relatively modern. The alternatives come in many flavors: ayurveda, acupuncture, acupressure, homeopathy, traditional Chinese medicine, chiropractic, massage, aroma therapy, meditation, yoga, therapeutic touch, herbal remedies, reflexology, naturopathy, reiki (see pages 38 and 46) and more. These methods are low-tech, low-cost and involve a more personal relationship between doctor and patient. The focus is as much on prevention as on cure. In some cases, the main treatment appears to be a daily dose of plain common sense.

Take something as basic as diet. Folk wisdom tells us, “We are what we eat,” and “We dig our graves with our teeth.” The 2,000-year-old South Indian Tirukural advises: “The body requires no medicine if you eat only after the food you have already eaten is digested.” But the article on medicine in the 1992 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica naively states, “There are relatively few diseases in which specific diets are of proven benefit.”

“Not so,” rebukes Dr. Neal Barnard, president of the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, a Washington D.C. watchdog group. Citing the research of Dr. Dean Ornish showing the overwhelming impact of change in diet in treating heart disease, Barnard states, “In a few years, a patient who was not given a vegetarian diet after their first or second heart attack, and who then goes on to have another heart attack, is going to bring a malpractice suit saying, ‘Why didn’t you give me the best care?’ That will change doctors in an instant.” And consider that just a few months ago a massive analysis of 4,500 studies showed changes in eating habits could prevent up to 40 percent of the world’s cancer.

“The real explosion of interest in alternative or complementary medicine has taken much of the medical community by surprise,” explains Barnard, “because it is more powerful than allopathic medicine in so many ways. For example, to treat clogged arteries with a coronary bypass graft costs US$30,000 to $40,000 for one person. It is very dangerous, and you have a six percent risk of brain damage. Some people don’t survive the operation. In the best case, you have to do it all over again within six or seven years because the arteries block up. If, on the other hand, you follow the regime developed by Dr. Ornish–very low-fat, plant-based diet, modest but regular exercise, reducing stress in your life–without ever incising the chest and without ever filling a prescription, 82 percent of people have their blockages start to dissolve within the first year.” Those stunning results are attracting the serious attention of doctors, insurance companies, universities and the US government.

Acceptance remains an uphill battle. Barnard observes, “Doctors are certainly amongst the more conservative people there are. When you’ve learned a whole set of treatments and modalities, one doesn’t easily set those aside, even when there is compelling evidence that one should.” And when one adds the impact on income that will result from a shift away from expensive, high-tech procedures, the establishment’s considerable resistance to alternative medicine is easily understood.

In 1977, as a medical school student and devotee of Swami Satchidananda, Ornish conducted the first pilot study in which yoga was used to treat patients with heart disease. “Patients not only felt better, but even in a month in many cases we were able to measure improvements in the underlying heart disease and blood flow to the heart.” The study was repeated in 1980 and published in the Journal of the American Medical Association–the coveted “seal of approval” and the reason insurance companies may now cover his treatment programs.

“Part of why I spent 20 years doing research was to demonstrate how powerful simple changes in diet and lifestyle can be,” states Ornish. “We often think of advances in medicine being a new drug or a new surgical technique. People have a hard time believing that these simple choices–how we eat, how we respond to stress, whether or not we smoke, or how much exercise we get–can make such powerful differences in their lives, but they do. In my research, we’ve been using the very high-tech, expensive, state-of-the-art measures to prove the power of these very ancient, low-tech interventions.”

Therapeutic touch: A surprisingly widespread technique now finding its way into many allopathic hospitals is “therapeutic touch.” Nurses (mainly) are trained to sit near the patient, even during an operation (see sidebar, next page), talk to him, comfort him and by moving her hands around his body allow life energy, prana, to flow through her and rebalance the patient’s life forces–a process similar to reiki. As a result, the patient is more relaxed during the surgery, less likely to develop complications and recovers sooner. This practice was pioneered in the early 1970s by New York University Professor Dolores Krieger and Dora Kunz. It has spread widely in the nursing profession and won the acceptance of doctors because it works, even though there is no allopathic medical explanation as to why it should. According to the Nurse Healers Professional Associate of Pennsylvania, therapeutic touch is now practiced by an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 professionals , mostly in the United States and Canada.

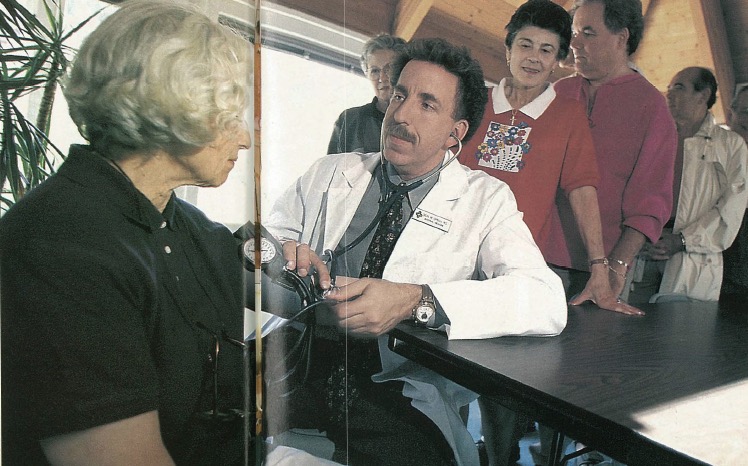

Ayurveda: The traditional Hindu system of medicine has yet to make a significant impact on mainstream medicine in the West. Maharishi’s Transcendental Meditation movement is working to popularize ayurveda in the West. So is Dr. Deepak Chopra. Individual practitioners such as Dr. Virender Sodhi (cover photo) and Dr. Vasant Lad (see My Turn, page 13) run successful clinics-cum-schools in the USA. In India, ayurveda is enjoying a resurgence. “Middle and upper class people who had shifted their allegiance completely to allopathy,” states Praveen Chopra in Life Positive magazine, “are again trying out ayurveda and other therapies after bad experiences with allopathy. The result is the blossoming of ayurvedic clinics and hospitals all over India.”

Enter the spirit: Direct advocacy of religion and spirituality is the final assault upon the machine paradigm of Descartes. “When you are dealing with cancer, serious illness, or chronic illness where the medical community knows that they have done their best, people often pull on their own resources,” said Dr. David Larson of the National Institute for Healthcare Research in Maryland, USA. The NIHR is a private, nonprofit organization that conducts research, educates and provides outreach on the relationship between spirituality and health. “Frequently the deep part of peoples’ belief is their spirituality and religion. There is strong research that shows faith is very beneficial in terms of preventing illness. You live longer if you are committed to your faith.”

Even among practitioners of alternative medicine, however, there remains a strong reluctance to fully bring forward the spiritual side of treatment. For example, Dr. Janet Macrae explains that she will not identify the energy manipulated in therapeutic touch as prana unless she is asked specifically about it. Other practitioners do not worry about what their views might be connected to. “Some people do feel a little at sea with things that seem to come from far away. Other people have the opposite response–they are intrigued and excited,” said Dr. Barnard. “When I talk about diets, I don’t mince words, I say vegetarian. As long as you reassure people that you have good research to back up what you do, you’ll have no problem. Ornish has been doing beautifully, he’ll use the word yoga.”

Why now? There are many theories that explain the recent interest in alternative medicine. “Touching, feeling and comforting is a human necessity which is missing in this country,” says Dr. Senthamarai Gandhi, a New Jersey internist. During her residency training in India, Gandhi said, the approach to patients was much more humanistic. Gandhi believes that alternative medicine brings simplicity to a patient whose mind is cluttered by the challenges and confusions of modern medicine. “The more we technologically advance and scientifically advance, it seems that the more disease we develop,” she said. “People might be unsure of why medical and technological advances do not answer their ailments, and for that reason, people may just want a more simple approach, a spiritual approach, to medicine.”

“The question is not: ‘Should Americans be trying these new approaches?’ ” states Dr. Ornish. “The fact is that many of them already are.” He finds that modern medicine often fails to address the underlying causes of disease. “If you do not treat the cause, it’s a little like mopping up the flood around a sink that’s overflowing without actually turning off the faucet.”

Enter the government: Public demand for more natural therapy caused the US government’s National Institute of Health to create the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM) in 1992 to evaluate other approaches. While it is true to some extent that this office was expected to do a certain amount of “debunking,” it has acquitted itself well in presenting a fair and comprehensive picture of the America alternative care scene.

US insurance companies have taken note of the increased use of alternative care. One reason is their customers are demanding they pay for it–in OAM’s 1990 statistics, only a quarter of the $13 billion spent on alternative care was paid for by insurance. For example, Oxford Health Plans, Inc., which serves 1.5 million people in the Eastern USA, just began reimbursement in 1997. Even before the change, a third of their members were seeing alternative care. More than half of US insurance companies are expected to follow suit over the next two years, according to Landmark Healthcare of California.

Education: The needed change in attitude toward alternative medicine is beginning to occur as medical schools adjust their training programs. An article in the September 1996 issue of Life magazine reported that 34 of the 125 medical schools in the US, including top schools like Johns Hopkins, offered courses in alternative medicine. Dr. Ornish has started a program in innovative medicine at the University of California. In 1996, the OAM and other government agencies officially recommended that “medical and nursing education should include information about complementary practices.” They also recommended training include information on alternative medicine, including philosophical or spiritual paradigms.

Harvard University has its “Mind/Body Medical Institute,” funded in part by the philanthropic and staunchly religious John Templeton, one of the world’s wealthiest people. A December, 1997, program offered courses “to continue to explore the relationship between spirituality and healing in medicine and to give perspectives from world religions and to discuss the physiological, neurological and psychological effects of healing resulting from spirituality.”

On the horizon: Many physicians feel it is inevitable for alternative therapy to be accepted alongside modern medicine. “I see an increasing integration of the two. It has been greatly unbalanced,” prophesies Barnard. “But surgery will always have a role for late stage cases. We will see an assignment of roles based on the strengths that they have.” This approach is called “complementary or “integrative” medicine.

“I see ayurveda as a much larger umbrella with a much greater perspective on the healing process,” states Dr. Halpern. “I would like to see ayurveda remain a separate, independent profession here in the United States. I see no reason for it to be incorporated into general medicine. In order for Western medicine to adopt ayurveda, either Western medicine would have to completely change its outlook on the understanding of the cause of disease, or it would attempt to extract out of ayurveda that which it finds useful, in which case ayurveda would become diminished and would loose its integrity as a healing science. I believe that ayurveda will follow a course similar to acupuncture and chiropractic and become the fourth major licensed health care profession in the United States.”

The final answer to health care really should be self-care. Must we simply trade one set of doctors and their methods for another? Or should we learn, as Mahatma Gandhi counseled, that every person can be his own doctor and learn to lead a disease-free life, especially through balanced, nutritious diet. He said, “I can cure 999 cases out of 1,000 by nature cure alone.” Many alternative doctors advocate taking personal responsibility for one’s illness, understanding that good health is the body’s natural state, and ill health is generally a result of poor diet, lack of exercise, stress and unhappy, unproductive life styles. Unless we take that advice and apply it in our lives, we remain dependent upon others for our well-being. Consider the old Indian saying about the limits of medicine–“If the patient is lucky, the doctor becomes famous.”

RESOURCES: US GOVERNMENT OFFICE OF ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE, POST OFFICE BOX 8218, SILVER SPRING, MARYLAND 20907-8218 USA, WEB SITE: http://altmed.od.nih.gov; DR DEAN ORNISH, 900 BRIDGEWAY, SUITE 1, SAUSALITO, CALIFORNIA, 94965 USA; PHYSICIAN’S COMMITTEE FOR RESPONSIBLE MEDICINE, 5100 WISCONSIN AVENUE NORTHWEST, #404, WASHINGTON, C.C. 20016 USA

PRANA

Therapeutic Touch

Retired department store manager Joseph Randazzo, 69, lies on an operating table at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York City in the throes of a triple coronary bypass,” opens an eleven-page 1996 article in Life magazine on alternative healing. “The cardiothoracic surgeon has plunged his hands deep into Randazzo’s chest cavity and works to bypass a clogged artery.” At the patient’s head during the two-hour operation, the article goes on, “The hands of Helen McCarthy, a nurse trained in therapeutic touch, hover a few inches above Randazzo’s pale forehead, making gentle circular movements, as if polishing the air. McCarthy believes that a person’s energy field extends beyond the skin into the air around him and that by consciously directing the flow of energy through her hands to the patient’s body she can–without even touching him–help him relax and stimulate his recovery. When she feels an area of congested energy, her hands linger over that spot, smoothing it out.”

“The sight of a surgeon and an energy healing working side-by-side in one of this country’s most prestigious hospitals has a forbidden air. If [rap singer] Snoop Doggy Dogg were to share the Carnegie Hall stage with Isaac Stern, the partnership would be no less incongruous. But this scene is just a particularly dramatic manifestation of an extraordinary détente taking place in American medicine.”

Yet there is irony here. Had the patient adopted another kind of alternative therapy earlier–better diet–he might have avoided his clogged arteries altogether and not needed therapeutic touch to help him survive major surgery.