BY ARVIND SHARMA

Karma is a key Hindu concept not always easily explained. Comparing it with the gravity, however, helps to illustrate how it works. Obviously, the law of gravitation existed before Newton discovered it. Similarly, the law of karma was actively at work long before some ancient sage first consciously came to understand it. Both these laws apply equally to everybody, regardless of race, religion, nationality, sex and sexual orientation. And they did so before either was understood.

The fact that our actions on Earth are governed by the law of gravity does not mean that we are frozen in place and cannot move about. It simply means we have free will within limitations. We can run, for instance, but we cannot fly. Similarly, the fact that our experiences in life are governed by the law of karma does not mean that we are helpless and live at the mercy of fate. Again, it means we have free will within limitations. We can purposefully improve our lives, but not without facing and accounting for past misdeeds.

All of the physical experiences that I have on the Earth pleasant or unpleasant, good or bad are under the influence of gravity. In a broader sense, all of the experiences that I have in life pleasant or unpleasant, good or bad are under the influence of karma.

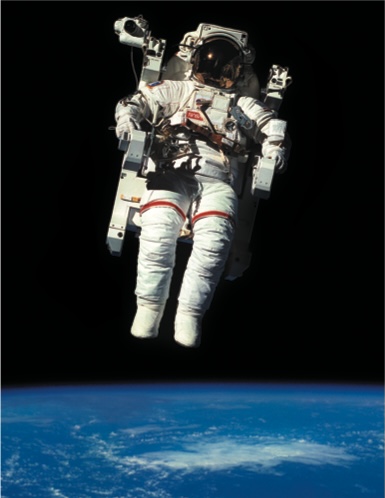

When an astronaut travels in space outside the range of Earth’s gravitational pull, he exists in a state of zero gravity and has experiences that no one on the Earth’s surface has ever had. When he returns from his space travels, he can only try to explain it. Yet nothing he can say can duplicate that experience he has had for others.

Hinduism claims that it is possible to travel beyond karma to a state of no karma just like the astronaut can travel beyond gravity to no gravity. If this is true and it has been done, those who did it experienced something none of the rest of us have. These jivanmuktis (enlightened beings) can try to describe their experience to others, but nothing they say can produce that liberated state in the lives of those who listen.

The astronauts who have experienced the gravity-free zone know that it is possible. They don’t have to be told. The jivanmuktis who have experienced the karma-free zone know that it is possible. They also do not have to be told. Both the astronaut and the jivanmukti know what they know from their personal experience. No one can take that experience away from them. However, this experience that cannot be taken away can also not be given away, which leaves us with a question: How can those who have not had the experience be expected to understand or believe those who have? They must take their word for it. This is faith. Faith must suffice until experience takes hold.

How might we experience the karma-free state? Just as we achieve a state of zero gravity by performing a certain series of appropriate actions while under the influence of gravity, so can we achieve a state of zero karma by following a specific pattern of activity while under the influence of karma.

The space shuttle itself is designed to deal with gravity. When we walk toward it and climb into it, we do so under the influence of gravity. As we launch, we are contending with gravity. We are not concerned whether the gravity is good or bad. We are focused only on the effects of gravity with an aim of transcending gravity into its absence. In so choosing to perform these actions, we have necessarily given up options to act in other ways for other purposes. By giving up all actions not relevant to the process of going beyond gravity, it becomes possible for us to eventually achieve our goal of experiencing zero gravity.

Similarly, in order to reach a karma-free state, we must give up not only bad karma, but good karma as well. We must perform only that karma which is appropriate for the attainment of zero karma. Just as the concept of good gravity and bad gravity is supplanted by considerations of gravity and no gravity, so also can the axis of good and bad karma be exchanged for one of karma and no karma, when one seeks moksha, or liberation from birth and death.

Arvind Sharma is a Birks Professor of Comparative Religion at McGill University, Montreal, Canada