BY RAJIV MALIK

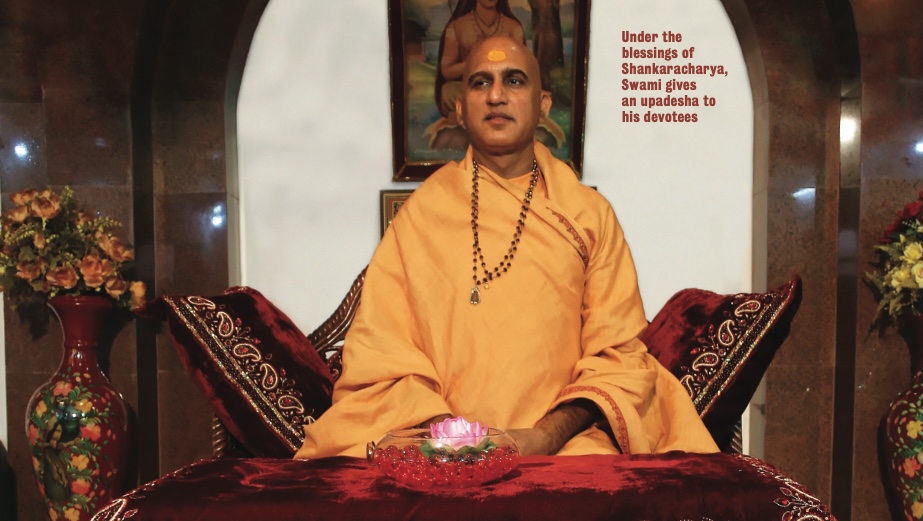

Sri Avdheshananda Giri Maharaj, Acharya Mahamandaleshwar of the Juna Akhara, received the 2008 Hindu Renaissance Award from Hinduism Today. A guru to thousands and an inspiration to millions, Swami Avdheshanand has initiated more than a hundred thousand sannyasins, transformed lives with his social initiatives and led Hinduism’s largest monastic order into the 21st century.

Hinduism Today correspondent Rajiv Malik investigated the life of this modern-day saint and the influences that shaped him into a dynamic leader and a steadfast defender of Hinduism.

AN EARLY YEARNING FOR GOD

“When you develop a craving to know the Truth, the mountains and caves start attracting you,” Swami Avdheshananda Giri told Rajiv. “In 1980, that happened to me.”

Hindu tradition holds that one should no more inquire about the past of a sannyasin than about the source of a river. The meager stream at the beginning of a Ganga or a Nile says nothing about the river’s greatness, its torrential waters that feed countries and give life to millions. Tradition advises that we should just be thankful for the abundant waters. But when a sannyasin does talk about his path, it is to encourage others and inspire seekers. Last year, during the Guru Purnima celebrations in New Delhi, Swami Avdheshananda shared with our reporter some of the steps of his quest.

Swami remembers that it was the year 1980 in northern India when an unusually inquisitive young man arrived at conclusions that would later guide his spiritual progress. He realized he did not understand life, nor did those around him. He longed for a truth that, he reasoned, could only be found at the feet of those no longer influenced by the world. Thus began his search for a satpurusha, a soul who had realized the Truth.

Wandering for months at the lower ranges of the Himalayas, the seeker realized he needed a teacher to guide him, one who was spiritually awake and blessed close connection with God. The young man, who would one day become Swami Avdheshananda, found his guru: Swami Avadhoot Prakash, a rare and elderly sage, expert in yoga and learned in the ancient sacred Hindu texts.

Under the master’s tutelage, in the cold foothills of North India, he studied the scriptures and developed a taste for Sanskrit, the language of the Gods. Eventually he received from his first formal initiation (diksha) as a naishtika brahmachari, opening doors to deeper yoga practices and confirming his aspiration to one day renounce the world.

His resolve was soon tested when Swami Avadhoot Prakash Ji Maharaj left his mortal form. The young novice did not falter. He continued his practices and inner achievements, having faith that he remained under the protection of God and guru.

In 1985 a very different, matured man emerged from the sacred caves. The yogi approached the revered Swami Satyamitrananda Ji Maharaj of Bharat Mata Mandir, a beloved former teacher. From Swamiji he received sannyas diksha, entering his new brotherhood, the holy Juna Akhara, Hinduism’s largest order of renunciate monastics.

Until now, he had been free and detached, an inner explorer, who gave little thought to the external world. But after donning the kavi robes of the sannyasin, he became a teacher. Accustomed to the practice of mauna (silence), he had little idea how important his lectures would become to so many.

Spending more and more time in teaching and social work, he became convinced that he must become an agent of social reform, not just social help. This, he saw, had to be done through the transformation of the individual, based on the precepts laid down by Hindu saints of yore. Swamiji became a katha vachak of the Juna Akhara–a speaker and storyteller–traveling almost incessantly inside India and abroad. The katha vachak is a master of Ram katha, employing stories, drama, music and debate to elucidate religious concepts. He must be able to speak for hours, keeping the audience immersed in the performance, entranced and spiritually uplifted. The best katha vachaks are famous in the Hindu world, the likes of Morari Bapu and Rameshbai Oza, but few are renunciate sadhus. In his first years as a Ram kathaka, Swami’s gift for oratory and his inborn clarity soon earned him the respect and love of eager seekers around the world.

A GIFTED SPEAKER

Rajiv Pratap Rudy, 52, a former high-ranking official for India’s aviation industry, explained, “Swamiji is able to strongly influence us, the common people, whether it is a youth or a senior housewife. He interacts with us not only about religion, but about all of our lives and interests. Swami speaks in a modern manner, but rooted in tradition.”

Many felt an instant connection with the new katha vachak in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The young sannyasin gradually became popular as a guest and a speaker. Swami told Hinduism Today that during those years he was quietly training himself to live more attuned to the ancient teachings of Hinduism, deepening his study of karma and spiritual laws, undergoing a transformation that would strengthen his conviction that seva, selfless service, is the core of what a spiritual aspirant should do today.

In 1998, Swami’s role as a world-traveling teacher reached a peak. Around the same time, the Acharya Mahamandaleshwar of the akhara, the highest leader of the order, passed away. Though a few saintly renunciates carry the title of Mahamandaleshwar–which translates as “supervisor of many monks”–only one is the Acharya. The position is not one of absolute authority, but rather of deep respect. The acharya is the public face of the time-honored organization. He guides the spirit of the akhara’s activities and initiates all new sannyasins joining the order.

Swami Avadheshanda recalls, “In 1998, the Juna Akhara formally decided to make me one of the Mahamandaleshwars. There was a formal ceremony and a religious ritual, in which my ‘Mahamandaleshwar Pattabhishekam’ was done. Immediately after that, I was also chosen as the new Acharya. This position is designated only by the assembled saints. No one can ask for it, and no one will be appointed from outside.”

As the Acharya, Swamiji assumed the mantle of guru for the akhara’s numerous devotees. He said to our reporter, “May God forgive me and I say this without any kind of arrogance, but I interact with thousands of people every day.” It requires stamina, dedication and a strong spiritual foundation to remain centered, and Swami found the answer in discipline. No matter where he is in the world, at 9am his doors will open to devotees. With three to four flights every month and an average of twenty days away from the main ashram, Swami finds it helpful to plan ahead in detail. Everything is scheduled, even the time allocated for each meal. It is a demanding social routine, far removed from his beginnings as a Himalayan yogi. “What keeps me alive is my meditation,” Swami says with candor. “I cannot live without meditation. It gives me energy, bliss, peace and vitality. When you close your eyes and sit in a proper posture, energy will grow and flow at a very rapid speed. Just close your eyes and observe it. There is nothing more powerful than dhyana. Dhyana gives birth to you, it introduces you to your own Self.”

As the Acharya, Swami Avdheshananda also became the preceptor for several sannyasins who, like Swami Nachiketa Giri, were already part of the order and decided to work closely with him. Swami Nachiketa Giri shared, “It is the greatness of Acharya Sri that he has open-heartedly accepted me and other sannyasins who are working in his team. I am grateful to him because after our meeting my life was transformed. I have been associated with him for over one decade. Whatever sankalpam (decisions) we undertake are quickly and auspiciously fulfilled. We do them all for the welfare of the society and for the world.”

SERVICE TO OTHERS

“This is an era of service,” Swami Avdheshananda proclaims. Dressed in flawless robes but with his cellphone hanging on his hip, ready to receive calls about the coordination of many ongoing projects, he obviously lives by that dictum.

One new initiative receiving much of his attention today is the Bhopal Project, an outreach to educate the most promising minds of the next generation–not in the latest fads of the global marketplace, but in skills meaningful to Hinduism. Though barely under way, this project carries the full force of the Juna Akhara, which is well known for its successful social enterprises.

“In our Bhopal Project we will try to educate youth who are already talented,” Swamiji enthused. “We are creating an institute that will teach them Sanskrit and English primarily, but also Spanish, Chinese and French. Our dream is to teach the Vastu Shastras (sacred architecture), the Vedas, astrology, Ayurveda and our culture to these youth. This will be a higher learning institution to teach not only book knowledge, but also introduce them to nature and provide organic food for their meals from their own farms. We will prepare them to be sent to countries outside of India, to go out all over the world, spreading the message of the Sanatana Dharma.”

The candidates for this new ambassadorship of dharma are children selected from the schools run by the Juna Akhara and other related institutions. Sannyasins teaching at these schools act as talent scouts. The goal is not to create traditional pundits, but rather a new generation of professionals who can interact with other professionals and pollinate society with traditional Hindu values. They may become engineers, doctors or scientists or specialize in skills they learn at Bhopal, but they will be expected to always make a difference.

The most influential of Swami’s ongoing projects is Shivganga, a broad effort to help people in an arid part of Madhya Pradesh who live in difficult conditions (see sidebar about the project’s beginnings). Distinguished from other projects by its commitment to preserving the local’s customs and self-respect, it stands out for the efficiency of its methods and has brought extensive positive exposure in the Indian media.

Swami Naisargika Giri, president of the Sadhvi Shakti Parishad, and one of the few women initiated as sannyasinis by Swami Avdheshananda, says, “Swamiji has brought a revolution there. This was an area where people had not seen automobiles. Today they are good farmers, with enough water available. Some are moving out to get education in the cities. For centuries their only goal was to feed themselves, but now Swamiji has connected them to God by establishing Sivalinga shrines in their villages, which gives a higher purpose to their lives.”

The process is well orchestrated. Work begins by gathering young men who have completed a brief formal education and will live in the village for rest of their lives. Training happens during 3- to 20-day intensives in camps. The first step is to train them in team skills and group cooperation. Because the young men as seen as the heart of the village’s transformation, they are taught to lead and make informed decisions. In the middle of a remote, quasi-desertic area, they have classes on sangat (group interaction), udbhodhan (addressing the public), time management, event management, evaluation methodology and how to pass on what they are absorbing. And, perhaps for the first time, they see others believing in their potential.

Shivganga camp training moves from theory to action quickly. A typical program includes: 1) How to organize the village; 2)The importance of sports for youth; 3) Identifying village problems and their root causes; 4) Finding solutions; 5) Establishing a center for worship and bhajans. The initial projects spearheaded by the group are designed to engage and give confidence to all participants. First they orchestrate a festival for Lord Ganesha and one for Lord Rama, then hold a community sports event. Later, the budding entrepreneurs work on the water supply and build a permanent shrine or temple.

“We have constructed 350 to 400 dams,” exults Swami Avdheshananda. And, he adds, 1,300 new Sivalingas have been installed, one for each village. “We wanted to develop their faith in God. The villagers themselves worked to build them. In the past five years or so, the whole life of those people has been transformed.” While he is pleased with the results, Swamiji wants to go farther. “Now we want to provide better education and medical help.” The Shivganga yields humanitarian results and is also good for Hinduism. “Before we went there,” Swami continues, “large-scale conversion was taking place. That has stopped altogether. Before, no religious events were happening; now we even have Hindu priests officiating at festivals. It is with a lot of enthusiasm that I am sharing with you our extensive plans for that area.”

Undeniably, Swami’s vibrant personality has advanced the works of India’s largest monastic order to a new dynamic standard. But he is quick to point out that the cooperation within the akhara is so complete it blurs the lines between the organization and himself. “My projects, the Juna Akhara and myself are so merged with one another that they are just one for me.” And his team’s projects are manifold. They like great ideas and small solutions, trying to make India and the world a better place one step at a time, focusing on basic strategies–from breeding better cows to creating chemical-free farms of ayurvedic herbs.

Swami explained why he feels selfless service is so important: “Dharma is something that has to be imbibed and adopted in our lives. We ask that devotees spare some time and devote it to projects which serve all people, contributing with both funds and personal energy. We must treat all people as God. Their cities should be clean and green, their water pure. We should offer medical services and education. We are not claiming that we will change the whole world. But we want to appeal to the Hindu world. We must understand that wherever selfless service exists, prosperity follows. With samskaras and education, prosperity is bound to come. People will become self-reliant and self-confident. They will become strong. This is what I see for India.”

A HOST OF VENERABLE SANNYASINS

“The Juna Akhara is the supreme akhara of India in terms of seniority and number of sadhus. It is a huge gathering of saints,” says Swamiji with unabashed pride. The number of Hindu monks in India and abroad is not known; estimates range from three to five million. According to the Juna Akhara, its order alone claims 500,000 sadhus. In comparison, the Catholic Church worldwide counts 460,000 ordained men plus 750,000 women, who are serving full-time and under vows (according to a 2005 census from the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate).

Hinduism’s monastic structure is complex and organic. Most monks belong to a parampara (lineage) or a monastic order, such as the thirteen famous akharas. The Hindi word akhara translates as “wrestling arena” or place of debate, a reference to vigorous, yet friendly, theological discussions. The akharas vary in theology as well as size and influence; most are Smarta in practice, but three are considered Vaishnavite and a few are Saivite. There is plenty of respectful acceptance for different points of view among the groups, and no dominance exists. Other large orders exist outside the akharas, such as the Swaminarayan fellowship, the Ramakrishna Order and the Nathas of South India. Within each akhara, most sannyasins are also associated with one of the dashanami lineages (see sidebar on page 24). Adi Shankara, who originated the dashanami system and did much to revitalize and improve the structure of Hindu monasticism, is commonly thought to have founded the akharas as well; but they actually predate him by centuries.

Hinduism’s sadhus are in two broad categories, those who live in monastic communities and those who wander or live in solitude. The socially engaged Juna Akhara also has thousands of naga sadhus and maunis who strive to uplift the world by their silent existence, anonymously blessing society from secluded caves. Their lack of involvement maintains a certain fluidity in the monastic order; these outlying branches of the family prevent the Acharya from becoming too central to the structure. During the monumental Kumbha Melas, the mountain-dwelling sadhus join their brothers of the same akhara in a surprisingly harmonious weave, populating vast areas under colorful tents–and new sannyasins are initiated by the Acharya Mahamandaleshwar, usually by the thousands in a powerful event. “I have directly initiated around one hundred thousand sadhus in a period of eight years,” reckons Swami Avdheshananda. The ordination of sannyasins is perhaps his most important role, for those rare souls become Hinduism’s leaders, the living embodiment of wisdom and tradition.

THE INITIATION OF NEW SADHUS

The ancient rules that govern the initiation of sannyasins are found in the Vedas and in the oral tradition of each monastic lineage. “A candidate could spend anytime from three to twelve years in the company of sadhus before he is initiated,” Swami elucidates. “His teachers protect and preserve the seeds of non-attachment. They also assess if the bramachari’s renunciation is truthful and his disinterest in the world is firm. It is the Mahamandaleshwars and the managing sadhus of the akhara who decide who qualifies for initiation.”

The training of a potential sannyasin varies widely. Most candidates begin by joining the sannyasins in whatever tasks they do. An aspiring monk will naturally seek those who reflect his own affinities. Some join Sanskritists and masters of scripture; others are drawn to social service or yogic practices.

Vairagya (renunciation) and the degree of control that the aspirant has over his senses are the main qualifications. “You also have to be truthful and ethical,” Swami explains. “Your heart has to be full of compassion. You must be connected to your soul. Your inner being should be peaceful. If you are bereft of desires, you are ready to become a sannyasin.”

Once a disciple has been approved for the lifetime vows of sannyas, he begins a period of intense preparation. Swami Nityananda Giri shares, “Sannyas diksha is preceded by intense sadhana (spiritual practices), long periods of silence and extended fasts. For the final eleven days, we survive just on water from the holy Ganga. We don’t sleep during the final 24 hours either, since sannyas is seen as a profound awakening.”

The initiation, performed in seclusion, is a pact between the initiate, his guru and God. The rites begin with the future sannyasin throwing into the fire his clothing, his desires and his former self. In the consuming flames he sees the dissolution of his karmas and family ties, his ignorance and doubts. He then vows that his sannyas is not taken to fulfill any worldly aspirations, and his head is shaved. In the tradition of the Juna Akhara, sannyasins make a vow to renounce any contact with fire, which in the old times was necessary for housekeeping and caring for oneself. The next step is a samskara performed to liberate his ancestors from all obligations toward him and to liberate him from filial duties. The rituals continue, and the last ceremony in preparation to meet the guru is the cutting of the shikha, a hair tuft at the back of the head that symbolizes status and respect in society. The fully shaved head proclaims that the initiate no longer acknowledges distinctions between people. Finally, at the banks of a sacred river, the initiate meets the Acharya Mahamandaleshwar who confers upon him the mystic ordination called sannyas diksha and the guru mantra.

NEWBORN SADHUS, ANCIENT PATHS

The Upanishads explain six levels of renunciation, based on what few monastic possessions the sadhu has. In today’s Juna Akhara, the main distinction is between the unfettered naga sadhus and those who stay in society to teach seekers and instruct families. But among the latter there are clear subdivisions, as Swami Nachiketa Giri explains. “During their initiation, the saint [the acharya] passes on the samskaras to them according to their aspirations.” The half million sadhus of the Juna Akhara serve God according to the kind of sannyas diksha chosen by each. “Aside from the naga sadhus, there are the kutichars, the baudhiks, the hansas and the paramahansas,” Kutichars are those who live in a kuti (hut), stationed at one place, and remain available to society as counselors, guides and helpers, living frugally and fulfilling renunciate vows. Baudhiks are intellectuals–scholars, Sanskritists, learned ones who know the written and oral wisdom of the rishis of yore. Hansa sannyasins are teachers who travels as a group of sadhus, preaching the truth wherever they go. Paramahansas, like Swami Avdheshananda, are grand teachers, gurus who dedicate themselves to enlightening others, having no home or resting place, and never staying in the same place for more than three days.

Though all are vital to society, the dynamic hansas and paramahansas weild the most obvious impact in today’s world. This fact is exemplified by Swami Ananda Giri, a constant presence in the busy, orange-robed swarm that usually accompany the Acharya. Formerly a post-graduate in physics, Ananda Giri is a skilled helper who performs his tasks with devoted zeal. “First of all, I am a disciple of my guru, Swamiji. I do help him as his secretary, but our main relationship is that of guru and shishya. The truth is, I am hardly doing anything myself. It is he who is getting everything done through me.” This selfless attitude, which runs deep throughout this time-honored order, has created a dynamic, trustworthy group for Swami Avadheshananda’s ambitious endeavors. Under the Acharya’s leadership, they are carrying out a mission or service and sadhana, one day at a time, molding the future of the glorious Juna Akhara, while honoring its noble history, and holding high the peerless standards of Hindu monasticism. PIpi

THE HINDU RENAISSANCE AWARD

The Hindu Renaissance Award was created in 1991 by the founder of Hinduism Today to recognize and strengthen Hindu leaders worldwide. Swami Avdheshananda Giri was presented the award in August, 2008, at a grand satsang during his visit to the Sunnyvale Hindu Temple in California. Hinduism Today’s representative, Easan Katir, gave the following short address explaining the award’s spirit, its history and the choice of this year’s awardee.

The Hindu Renaissance Award is given by Hinduism Today magazine to leaders who inspire, strengthen and reinvigorate Hinduism and its millions of followers all over the globe,” Easan Katir explained. “Such peerless leaders can come in many forms, reflecting the diverse ways of our faith. Some are silent sages, mystics who take us to the heights of our own being by the force their own enlightenment. Others are tireless social workers, servants of Hindus in need, helping children, priests, villages, the sick and the poor, living the Hindu ideals of ahimsa and compassion. Yet others are scholars, intellectual champions capable of debating deep scriptural truths and fighting in many arenas to protect dharma. This year’s recipient belongs to more than one of these categories. Swami Avdheshananda Giri Maharaj was chosen the Acharya Mahamandaleshwar of the holy Juna Akhara and has excelled at the task.”

Previous awardees were Swami Paramananda Bharati (’90), Swami Chidananda Saraswati (’91), Swami Chinmayananda (’92), Mata Amritanandamayi Ma (’93), Swami Satchidananda (’94), Pramukhswami Maharaj (’95), Satya Sai Baba (’96), Sri Chinmoy (’97), Swami Bua (’98), Swami Chidananda Saraswati of Divine Life Society (’99), Ma Yoga Shakti (’00), T. S. Sambamurthy Sivachariar (’01), Dada Vaswani (’02), Sri Tiruchi Mahaswamigal (’03), Dr. K. Pichai Sivacharya (’04), Swami Tejomayananda (’05), Ramesh Bhai Oza (’06) and Sri Balagandharanathaswami (’07).

HOW THE SHIVGANGA PROJECT BEGAN

“If you ever need to cross Jhabua, do so in the day time, never at night. There the tribals carry bows and arrows.”This rather foreboding warning was all that neighbors had to say ten years ago about Jhabua, a poor region of Madhya Pradesh dotted with impoverished, depressed villages a few hours from Indore. Today the villages are like small jewels in the arid landscape. The transformation was brought about by the Shivganga project and its hundreds of volunteers.

“It was in 1998 that Mahesh Sharma, a social worker and devotee of Swami Avdheshananda, first visited Ghatia, just one many villages in the Jabhua area, which is notorious as dangerously distrustful of strangers. He was shocked by the poverty of the villagers, but impressed with their intelligence, candor and warmth. Determined to help, Sharma extensively traveled and stayed in many villages, making friends, learning the customs, traditions and dialect.

“In the old days,” the villagers told him, “we had enough water and crops to stay where we were. People did not fight. Now food is scarce, and we have poverty and quarrels. But when the government and the city-folk come to help, they do not connect with us. They give us a lot, but they make us dependent on their ways.” Mahesh Sharma realized, then and there, the need for a different kind of social work.

Changing the situation began with a careful plan and much selfless work. Maps of the region were drawn and the problems the villages faced were studied in depth. The sannyasins contacted Shri Rajendra Prasad, an award-winning engineer from Rajasthan, for guidance and technical support. Water scientists were consulted and a strategy was created that involved no money from the government, relying primarily on the dormant capacity of the villagers themselves. A jal sansad (water parliament) was created to plan broader solutions, such as new dams.

With the support of the Juna Akhara, under the blessings of Swami Avdheshananda, the Shivganga project was begun in Jhabua. Its mission statement is, “Self-reliance is essential for development. Self-respect is essential for self-reliance.” Hundreds of social entrepreneurs and volunteers are laboring in the ongoing effort to restructure and revive villages. Work is progressing, at different stages, in 1,300 villages, helping to uplift and inspired hundreds of thousands of people and provide them with sustainable supplies of food, water and the basic amenities of life, including schools, places of worship and joyous festivals.

SWAMI’S DEVOTEES SPEAK THEIR HEARTS

“We met him due to the will of God. Swamiji is not just an individual. He has a full ancient guru tradition behind him. At any time if I need any spiritual guidance, I can always talk to him. He speaks so clearly. The transformation that has happened to me is that I learned to love everybody.”–Shailaja Nair, a housewife from Mumbai

“My parents and I used to see Swamiji on television, but one night he came to us in our dreams and asked us to go meet him. Since then my life was transformed. In my career I received so many blessings. Today I am a complete vegetarian and I now respect my parents much more. Everything that happened to me is so positive that I am never going to leave Swamiji.”–Shantanu, 27, an operations manager from New Delhi

“My life was a journey of seeking that came to an end when I met Swamiji. Today I finally feel that all I need is within my reach and I do not have to look around aimlessly anymore. I just have to work, improve myself and the things I want to change. Now, whoever I am is because of Maharaj, and whatever I have belongs to him.”–Sheel Singla, a housewife from New Delhi

“My whole family have been his devotees for fifteen years. Swamiji has taught us the technique of living. He has given us strength and motivation to work hard in life. He also taught us to live like a family, and we understand each other much better now. He has taught us to love ourselves and help others as we help ourselves. For all this we are so happy to be in his presence. But even when we close our eyes, we can see him.”–Sonia Jindal, 25, a fashion designer from Punjab

ADI SHANKARACHARYA & HINDU MONASTICISM

Adi Shankara (788-820) is a central figure to the Bhakti movement, a wave that swept across India in the 9th century and brought many Jains and Buddhists back to Hinduism. He was a quintessential nondualist. His Advaita Vedanta teachings can be summarized thus, “Brahman (the Supreme Being) is the only truth. The world is an appearance. There is ultimately no difference between Brahman and the atma.” He revived and empowered the Smarta sampradaya, one of the four major denominations of Hinduism. Shankaracharya’s influence and philosophy were perpetuated by the creation of monastic protocols and centers which remain influential to this day. From Adi Shankara came also the dashanami orders (Sarasvati, Puri, Giri, Bana, Tirtha, Parvati, Bharati, Aranya, Ashrama and Sagara) of which sannyasins from all the akharas are often members, as Swami Avdheshananda Giri is associated with the Giri dashanami. The akharas and the dashanami system harmoniously overlap in a colorful tapestry.