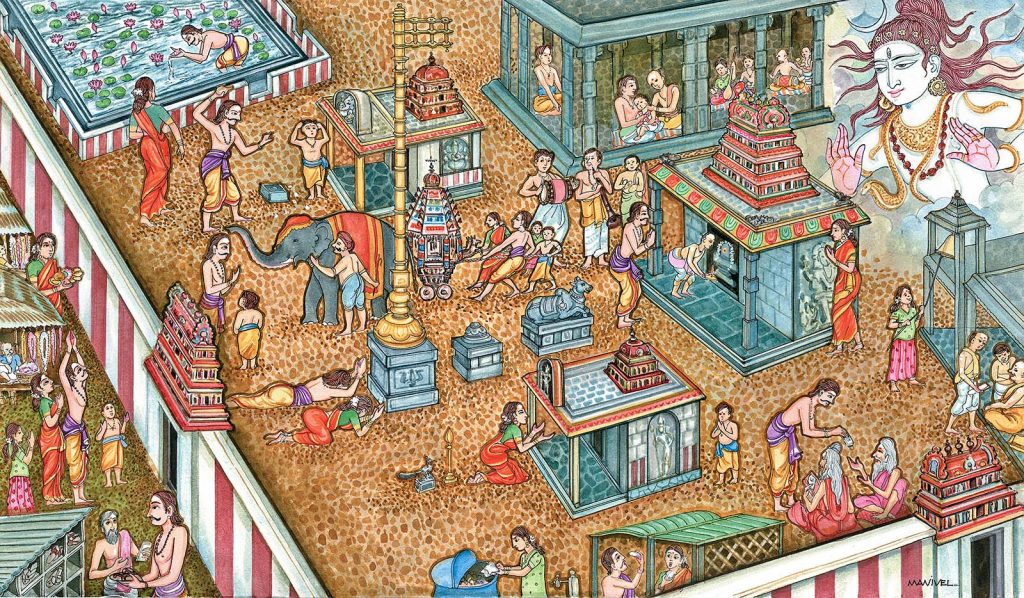

Historically, the Hindu temple was not only the religious center of each village but a social, cultural and even business/financial hub

By Rutvij Holay, 17

Since perhaps the beginning of time, teenagers have been sneaking out of the cave, hut or house to hang out with their friends. When we think of these hangouts today, perhaps the mall comes to mind—though increasingly it tends to be online platforms like Discord. Yet, when we go back even further—centuries further, in fact—we find that the traditional hangout has often been the local mandir.

Indeed, if one takes a look at the older literature in local languages (which tend to be less intellectual, primarily consisting of contributions composed by village folk), there are references to young people sending coded messages to each other, telling them to meet up in the mandir at night. To many modern teens (and the parents who struggle to get them into mandirs in the first place), especially in such a materialistic world, this may seem rather confusing: why would anyone decide to have fun in a place as boring as a temple? Perhaps more importantly, why should anyone care today?

Both are important questions. In their answers lies the secret to making our mandirs cool again, primarily because, in the past, all the cool things happened in the mandirs. While there certainly were pujas, other events—such as dances like Bharatanatyam and Kathak and various sangeets (group singing) and dramas—were regularly held in the mandirs. That these art forms often told stories to the audience made them more interesting, and perhaps even like the movies of their time. Especially in rural areas where literacy was rarer, as it was in much of the world, books were evidently not an option for entertainment, making such pastimes all the more entertaining compared to the alternatives.

The Temple’s Many Functions

In such a way, the mandir became the equivalent of a movie theater: people could come together and enjoy a good story with friends and families. Perhaps even better, because, in cases where there was only one mandir in town, the vast majority of people in the village (or, in the case of bigger gatherings, multiple villages) would come to these events. Given that these were agrarian societies, with no “offices” where colleagues worked together, it would make sense that the mandir was one of the premier places in the village where people would gather.

People came to attend the mandir’s religious and cultural events as well as to exchange news, talk politics or just gossip. Surprisingly, mandirs were even a place of business. Sanjee Sanyal writes in his wide-ranging book on the peoples bordering the Indian Ocean, The Ocean of Churn, “Much of Indian classical music, dance, drama, sculpture, painting and other art forms evolved in the temples rather than at the royal court. What is less appreciated is that the temples were key to the financing of trade, industry and infrastructure building. It is well known that medieval temples were very wealthy, but the common impression is that this wealth was mostly due to royal grants. In reality, the reason that the temples accumulated so much wealth is that they acted as bankers and financiers!”

Invasion’s Impact

At the same time, however, as a result of all of these reasons, mandirs were targeted by invaders, and started to decline in their social prestige. As Muslim invaders (such as the Umayyads and Mughals) and Christians after them, began to attack India, one of their first targets was (and still is, in the case of countries such as Pakistan) the mandirs, in part because they were not only of religious significance, but also the cultural, social and in some ways, political center of the village. Taking them over meant that the riches of some of the biggest corporations in the world at the time would belong to the invaders. While large sites like Somnath and Pandharpur were rebuilt due to their religious importance, many Hindus did not have the resources to afford similar reconstruction of the smaller mandirs in many villages. When there was no mandir, there was no gathering place, and thus no place to foment dissent and promote an “idolatrous” culture. When these mandirs were broken, so too was, in many ways, mass resistance and the teen hangouts.

In the centuries that followed this destructive period, Hindus found a way to adjust to the lack of community centers by becoming much more decentralized. When there weren’t pandits around to explain the Sanskrit Ramayana, the Hindi Ramacharitamanasa grew in popularity. When no one in the village could read the tales in the Srimad Bhagavatam, people began to listen to folk tales surrounding Radha and Krishna instead. And as the temples grew fewer, people instead heard the Bhakti Movement’s Saint Tukaram remark that the body is God’s mandir.

Religious Transmission Changes

As a result of these foreign invasions, the onus for passing on cultural and religious values increasingly began to fall more on individual parents, rather than on institutions like mandirs. Thus, the development of many of the art forms the mandirs encouraged became decentralized as well, with dance (which would later on be banned by the British in the mandirs that still remained) and music being passed down from parent to child, more so than guru to shishya, a practice which continues, in some ways, to this day.

Today’s Challenges

While this decentralization took away much of the mandir’s historical importance, perhaps what has drawn people away from it the most has been modernization. Today, there are more things to do on our devices, especially as they’ve become more interconnected. The mandir and, for that matter, many things not on a screen have become more boring to kids who have more options than their forefathers ever had.

In many ways, this problem has increased as the reach of technology has grown. Even when I was younger, though we had devices in the house, the ability to connect with friends without leaving the house was still miniscule, and not something I had access to growing up until middle school.

That may be why, though not as deep as it was two thousand years ago, my friends and I felt a deeper connection to the mandir than most. Growing up, the mandir I remember most visiting was the Sarva Dev Mandir in Oxford, Massachusetts. During that time, I would stand around with friends for a few aratis, and then go play tag through the mandir halls.

While normally such behavior would have been frowned upon, our mandir had a big room to the side where prasad was served after the aratis. In the meantime, the room was empty, and ours to frolic around in. We would play with any kids in the temple, including those whose names we never knew, creating a larger bond between us not as individuals, but as a Hindu community. Even more importantly, while we were in a separate room, we were always within earshot of the prayers going on. While it didn’t seem like it, some of those aratis became ingrained in our heads, and were subconsciously memorized by us.

While I was talking with old friends, some of whom played with me in this mandir nearly a decade ago, many of them agreed with my sentiments. One, Jay Manjrekar, who now is in 11th grade and resides in San Diego, California, said, “These mandirs represent my childhood. Not only was the mandir a way for me to connect with my culture, but it also allowed me to make friends. I vividly remember Navaratri in 2012, when we had a blast. Looking back and reminiscing on those times makes me feel even closer to Hinduism.”

Some of our other friends, who were growing up on the other side of the country during that time, also agreed that the mandir helped deepen their bond with Hinduism, with one, Shivam Garg, recalling how whenever he visited, he loved to read “the stories on the wall, and eat the prasadam.”

Looking at this next generation of children, however, I rarely see anyone having the same experiences that we did. While I sit for bhajans at our local mandir, I seldom see kids running around and having fun, and I know that, despite the great memories my generation made at the mandirs, it is only a mere fraction of the memories our forefathers made at their local mandirs centuries ago.

The Next Generation

That brings us to the question of utmost importance: how do we make sure the next generation is able to have a bond at the mandir that is much greater than ours? How do we take these kids away from the metaphorical mall (and, perhaps more relevant to modern times, their ever ubiquitous phones) and put them back into the mandir? How do we make the mandir cool again?

To start from personal experience, it may be best to make sure mandirs are as “youth-friendly” as possible. While parents can drag kids to the mandir all they want, if they don’t want to pray, it becomes hard to change that, and the experience will only embitter them in the future. Rather, having a space for the older kids to hang out, and perhaps a larger space for younger kids to run around will make them willingly come to the mandir, and make good memories around the mandir in their minds. Perhaps more importantly, by merely being in such an environment, they will be exposed to their mother tongues, prayers, and anything else that they should imbibe to be good Hindus.

From there, bringing back plays, musical performances and dances on a regular basis is absolutely necessary. Historically speaking, there were rarely days consisting solely of prayer, as dances and sangeet used to be an essential part of any worship ceremony. Today, however, they seem to be relegated to festival days or talent shows. By bringing back such forms of entertainment, we give the youth something to see and do, and thus motivate them even more, especially if their friends are amongst the performers.

From there, it gets a bit harder. Even if we bring back the old mandirs where kids used to frolic, and bring back the entertainment they had, we still have to contend with the issue of modernization and technology, and the fact that if someone does not wish to go to the mandir, there are so many other things they can do.

To start, even though most kids may not have businesses that need banking, they all do have hopes for their future, and material wants that can incentivize them to come to any place. The mandir, wherever possible, ought to provide those.

There are so many areas where mandirs need help, whether it be the distribution of food, cleaning and maintenance, or simply advertising for festivals and whatnot. If other initiatives surrounding entertainment are added in, those are more opportunities for youth to get involved, and even take on leadership roles.

Someone skilled at cooking could, after some initial training, oversee the distribution of prasadam completely on weekends, while a skilled dancer could choreograph performances for the enjoyment of the audience every Sunday. For those who are more outgoing, perhaps fundraising for the mandir or coordination of interfaith visits could be done. Especially for those who are spiritually inclined, an “internship” with the purohits may provide an opportunity for them to grow their skills, and help preserve our future. Others could help generate the temple newsletter, or add to its website.

For those youth blessed with a spiritual interest, but who have less religious parents, such initiatives are a better way for them to increase temple engagement and convince their parents to take them to the mandir each weekend. Perhaps while these parents wait for their kids, they may become enthralled with everything happening in the mandir, and find the same joy in visiting that their forefathers did. In this way, our mandirs, while they may not be banks like they used to be, will provide a way for people who come to visit to benefit materially as well as spiritually.

In Conclusion

Of course, such steps are no guarantee that our mandirs will become the hangout spots that they were during the time of Kalidasa and Chandragupta Maurya. Various powers, over centuries, have worked hard to dismantle traditional Indic systems of life which had the mandir at their center. Aside from that, we live in a different world where, for all faiths, the worship house is becoming less relevant to a younger generation. It may take centuries to restore our mandirs to their original position in our culture.

That is not to say, however, that we should not get started. Before many invaders even existed, our mandirs were the center of Hindu society, and with their destruction, so too was destroyed India’s golden age. If we wish to preserve Hindu society, and ensure that our next generation cares for our way of life as much as we do, we must take steps to make our mandirs more relevant in their lives, and thus make our mandirs cool again.

About the Author

Rutvij Holay, 17, of Irvine, California, is an executive-committee member of Americans for Equality PAC and a Hindu political activist. He is presently working with his school district and a textbook maker to change how Hinduism is depicted in education. He can be reached at rutvij.holay@gmail.com.

You wrote an article stating exactly what I need at my age… in my 40s! Something engaging and relevant to my life growing up in the US. I need it less intimidating and more accessible for myself and my children. How can we bring such a thing to Oregon?

What I want at my temple: community, language classes, art, dance, performance, prayer, camp, activities, and cooking. I think it can all be there. I feel like I can’t participate, that there isn’t a place for me to belong in this city of a million people.